In Defense of Economic Liberty

Taking an important idea back from the right

My whole life I've seen the tongue bath that "small business owners," "entrepreneurs," or "job creators" have gotten from the right—and often from the Democrats as well—and been constantly struck by the divergence between that rhetoric and the reality of "schmuck who inherited five McDonald's franchises." For too long, "economic liberty" has been the rallying cry of the landed gentry demanding lower taxes on their profits and fewer regulations on their capacity to exploit their workers—the rallying cry of the rentier class with their hand out for a tax cut.

And yet. I am increasingly struck by the ordinary economic freedoms that the majority of people—people who are neither John Galt nor John Dutton—participate in. Housing is an illustrative example. Choosing where to live is a kind of economic decision—a way of participating in the total distribution of productive and consumptive forces of society. More: it is a profoundly important one, because it affects where you get a job, where you go to school, how close family and friends are. To speak only from personal experience—I moved from one country to another for college, and then again, to a different college; moved to a new city for graduate school; moved across the country for work, then bounced across the continent yet again (work again). When you choose to give up your apartment in one city, seek out education in a different one, find a career that satisfies and remunerates—that, too, is economic liberty. When you don't have to ask your neighbors or your government for permission to move—that, too, is economic liberty.

The program of this essay is therefore simple: to defend the concept of economic liberty from those on the left who are suspicious of it and those on the right who abuse it. We must re-center economic liberty as one of the core features of a liberal society—a core good for both free individuals and free society. The thesis of this essay is, therefore, equally simple: it is good when individuals have the ability to just make choices about their employment, or entrepreneurship, or technological tinkering, or where they live, and do so without asking permission. It is good when individuals are free. But how is this to be achieved? That is the tricky part. The concept of "economic liberty" is encrusted with a bit too much grime and a few too many barnacles. What economic liberty, really?

Let's start with the right-wing interpretation. To simplify a long intellectual tradition somewhat: economic liberty consists of a few fundamental individual rights—life, liberty, and property, in Locke's old formulation. The government maintains the security of property and the validity of contracts, and anything else is tyrannical overreach. What you do with your property, what contracts you enter into—that's your economic liberty. And yet. If you are dangling off a cliff, and I stop by to offer you a hand up—in exchange for, say, a lifetime of servitude—that freedom doesn't seem to be worth very much.

The example is extreme. But it highlights the general problem: gulfs of material wealth and power create wildly imbalanced playing fields, and these material imbalances enable exploitation and domination. Your economic liberty doesn't mean very much when there's only one choice in front of you—as the particular prisons that were Gilded-Age company towns made perfectly clear. One store, one landowner, one employer, and somehow the terms of all these "free" transactions interlocked to ensure that the workers always wound up trapped in debt slavery.

Now let's turn to the left-wing interpretation of economic liberty. You might interject here that there is no such thing, that it is precisely economic liberty that the left disdains! And yet, I would argue, the left is also committed to a concept of freedom for individuals to chart their course through the great machine of production and consumption. The left sees individual workers buffeted this way and that by the great forces of capital, and wishes for a world in which workers seize control of their own destiny—the means of production, in a famous phrase. These days this is typically framed by the concept of "economic democracy." Just as democracy meant the transfer of political power from kings to the people, by bringing the economy under democratic management, we can transfer power from capital to the people.

Or so the argument goes. When there's a bureaucrat standing in front of you reminding you that you may not move closer to your family, you may not go to college, your career has already been carefully determined and it involves a mop and a bucket, forever, then the fact that "the people" in some way and at some remove politically control the economy is cold comfort. The example is a bit extreme—or, arguably, a cliche. No one today is advocating for a return to Soviet-style central planning, at least not openly. More often there are gauzy paeans to local democracy and citizens' councils, each managing the economy of their local community in a democratic, accountable way.

But here is a secret truth: local economic democracy is not a pie-in-the-sky intellectual proposal, and we do not need to resort to armchair dystopias—or utopias—to understand its effects. The American housing market is an actually-existing experiment in economic democracy, and the evidence of that experiment's results is all around us, in the form we call "the housing crisis." Across America, decisions about zoning, land use, and development have been devolved down to the hyperlocal level, where the results of "citizen voice" meetings, surveys, and town halls are used to decide everything from the location of new bike lanes to the development of new apartment buildings on abandoned lots. The effect is to take decisions about housing construction out of the realm of individual liberty and put them in the realm of political control. And the result, everywhere this has been practiced, is bone-deep NIMBYism and an omnipresent supply crisis. Vacancy rates are as low as they've been in decades, rents and mortgages are skyrocketing, and ordinary people are locked out of the neighborhoods they want to live in.

The housing market presents the appearance of "economic liberty" to consumers. No bureaucrat is checking your hukou when you want to move to a new city—instead, you are faced with the delightful freedom of deciding whether to accept your landlord's latest rent increase or wind up on the street. But the production of housing is radically unfree. If you want to build new housing for precisely that person looking to move to a new city, then you better have your hukou zoning variance in order. And if there's nowhere new to move, if there's only a fixed supply of housing in the most desirable cities, then you are faced with a choice: outbid someone else, or give up on your dreams.

The fundamental problem with "economic democracy" is not the lack of a sufficiently large calculator, and stands little chance of being resolved by "AI." The problem with economic democracy in every instantiation is that it separates the principal from the agent. People are, generally, terrible judges of what other people truly want. You can survey the public, if you like, but you will rapidly discover that what every American wants is a big house in a quiet neighborhood with free parking that is two minutes from shops, work, and school. It is only when there's actual cash on the line that people are forced to prioritize—to make their own calculation of costs and benefits. Worse than the information problem, arguably, is the incentive problem: even if a hypothetical AI—or hypothetical bureau of psychohistorians—can perfectly discern what you really want, what mechanisms exist to keep them caring about it?

This is one of the more common failure modes of planned economies: decision-makers largely uninterested and uninformed about the needs of the people beneath them—about the true costs and benefits of their policies—steering their nations towards stagnation and poverty. And this is precisely what our great experiment in economic democracy (housing edition) has revealed: local authorities obsessed with absurd details of facade and setbacks and lot size and floor-area ratio with no concern for the costs these obsessions impose on ordinary people who just want a place to live.

The problem with economic democracy, frankly, is that it empowers the worst busybodies you know to go around playing with other people's money. That way does not lie freedom, just another kind of tyranny. I invite anyone who believes in the inherent virtue of local democracy to attend a meeting of their local planning commission concerning a new development, and see what is actually said in those meetings. To take just one example from my own city, to build a new row house on a block full of row houses where an old row house already exists, the Fineview Citizens Council had to go begging to obscure government boards for a special approval—which, of course, they did not receive. "Economic democracy," certainly. But you will not convince me this has in any way enhanced or respected the capacity of individuals to chart their own course in the economy.

So what is economic liberty? We can see both left and right as concerned with economic freedom and worried about economic domination. Those on the left obsess over private domination, and flee to the refuge of political control; those on the right obsess over political domination, and flee to the refuge of private action. The trouble here is that both left and right interpretations of economic freedom act as if states are, frankly, magic—as if the mere fact that an action is "state" somehow guarantees that it will be used for ill (the right) or that it will be used for good (the left). But there is nothing morally special about states. Domination is domination.

So what is economic liberty? Some might argue here for some list of rights that constitute such liberty—but such lists are continually being outdated by the progress of history. While these lists can be useful for international organizations looking to operationalize political principles in actionable ways, they will not do for real political theorizing. Just as the mere act of voting does not make a nation democratic—they "vote" in Russia, after all—just as real democracy requires access to political competition—so too does economic liberty require access to economic participation. This access is subject to two key restrictions: first, that that access is consistent with similar access by others; second, that the resulting system is in aggregate stable over time.

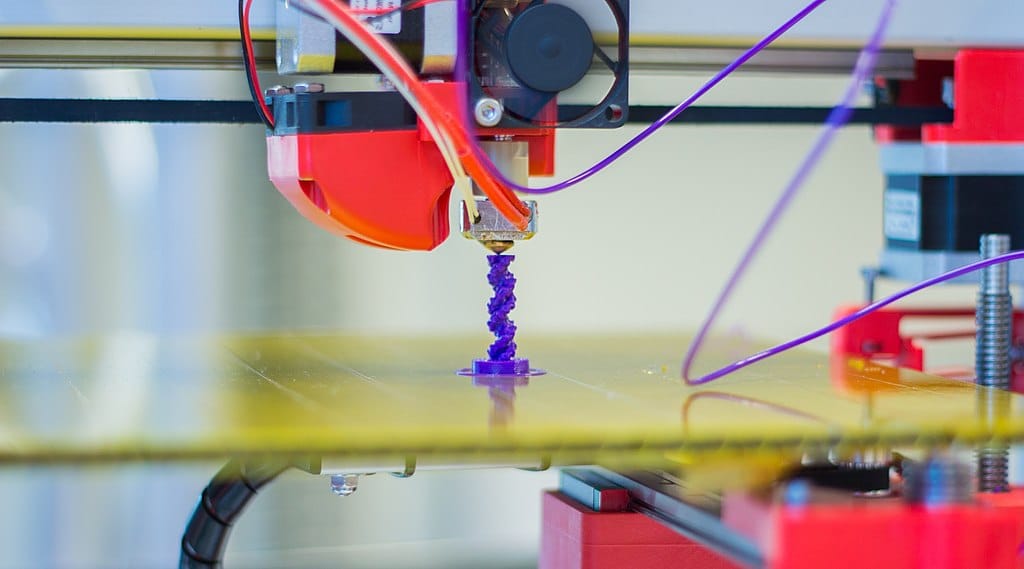

From this perspective, the maker-anarchists arguably have a clearer understanding of the problem and the goal than either left or right: "each individual should have the knowledge and tools to manufacture anything." The goal is to empower individuals to chart their own course through the great machine of production and consumption. A 3d printer in every garage, as they say. The problem of course is that the maker-anarchist proposal is deeply impractical; simply as a material matter not all of us can have an angstrom-class chip fab in our garage (and this is setting aside the problem of skill and knowledge). More strongly, even if we could, economies of scale and specialization ensure that we wouldn't: rather, we would all rapidly use that economic liberty to seek new and better opportunities—a worker in someone else's megascale angstrom-class fab can buy more from their earnings than they could make in their own garage.

So if not home chip fabs, then what does "access to economic participation" look like? Mere armchair a priori theorizing does not have a good track record at answering such questions. Rather, we must draw on the lessons of history: a powerful and professional central bank, robust public education, social and health insurance systems, environmental regulations, a professional judiciary, legislatures responsive to the popular will, and numerous other institutions that together provide individuals with the knowledge, skills, and material security necessary to chart their own course through a law-governed economic system of steady growth, high employment, and low inflation. Or, in other words, economic systems are not stable "on their own," because they do not exist "on their own," but always as part of larger societies. What is necessary, instead, is equal access to economic participation within a larger liberal system. Economic liberty cannot be considered independently of the larger political system—just as political systems cannot be considered independently of their economic systems!

Economic liberty is not an end in itself, but rather an essential aspect of liberal systems, and the great miracle of human flourishing called modernity—which is another way of saying, of deep and continuing relevance to the lives of ordinary people, who are constantly using that liberty to achieve better lives for themselves and their families. This is a liberty we have far too long denied when it comes to housing. It is precisely by giving people freedom to decide where to live and what to build free from "democratic control"—aka control by neighbors, by HOAs, by NIMBYs, by governments—that we enable people to pursue their own course of life. And it turns out that by enabling people to do this we make life better for all of us: more prosperous, more secure, more free. The way to achieve economic freedom is not "cut all taxes," but rather to on the one hand remove the regulatory obstacles to building housing where people want to live, and on the other ensuring that people have a decent enough income to afford some choice.

Featured image is Felix 3D Printer, by Jonathan Juursema