A Conversation About Liberal Democracy

[The following came out of an email conversation between Martin Gurri and Adam Gurri that took place January 16–18 of this year. The topic of the conversation was Adam Gurri’s essay What Is Liberal Democracy?]

Hey Adam,

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed your essay on liberal democracy. Happily, I found myself agreeing with most of what you wrote. That will make family gatherings less interesting but more chill, in that golden future when we’re allowed to have family gatherings again. Your four pillars of liberal democracy – liberty, democracy, law, and virtue – cover the intellectual waterfront, as far as I’m concerned. The inclusion of virtue in particular appealed to me, since, as you know, the influence of morality on politics has been something of a fixed idea of mine.

Of course, when someone says they “mostly” agree with your position, you wait for the other shoe to drop. And it’s true: I have questions. I propose to group them into three large themes, based on the structure of your essay. The questions may sound argumentative, and probably they are, but it would be pointless to turn this into a debate or disputation, since we are in accord on “most” fundamentals. That’s not my intention, anyway. What I hope to get out of this is insight into the next level of depth regarding your ideas about liberal democracy.

Dignity is awkward. You write: “The equal value and dignity of each individual person regardless of their station is a fundamental principle of liberalism.” Not only do I agree – I believe the dignity of the individual is, and must be, the prime directive of liberal democracy. Everything else follows. But it’s a problematic notion. Any Dostoevsky novel will teach you that dignity is hard to attain in practice. On what basis can we claim it exists? That basis was once Christian doctrine: king and peasant alike were pilgrims on the road to salvation. Later the Enlightenment tried to substitute reason and natural law. None of those principles are “self-evident” in a fractured, post-modern society.

I’m curious about the degree of importance you give to the equal value and dignity of the this individual – and how you define and justify the terms.

Democracy isn’t a job. You dismiss the notion of a popular mandate based on election results. Elections, for you, seem to be moments of corrective pressure applied by the voters on professional politicians regarding this issue or that. The process is entirely transactional. But that’s a little like saying that “love” is a series of transactions between two persons over a lifetime: true but insufficient. Politics, like love, is mostly transactional, but there are big moments: colony or independence, slavery or freedom, peace or war. Powerful swings in opinion – that is, in the accumulated dignity of the community – often decide the case. Do you agree that these exceptional events are central to the romance of democracy? Did the slave states commit a cognitive error in thinking Lincoln had a mandate to stop the spread of slavery?

I confess that I found your enthusiasm for “professional politicians” a little perplexing, since I never thought of you as much of a Platonist. How would you prevent professional politicians from developing professional interests and becoming a class apart? That is exactly what has happened to American democracy – I actually know someone who wrote a book about this! The rise of Donald Trump can be explained entirely in terms of a repudiation by voters of the narrow choices offered by the “elites,” that is, the pros. To perpetuate itself, a political class will spend government money on favored clients who will then vote for them: it’s the Godfather with the ballot box instead of the tommy gun. Boss Tweed was a professional in this sense – so was Harry F. Byrd. California today isn’t much different. Do you see a way out of this labyrinth?

You also place a lot of weight on political parties as a home for the professionals – but every mainstream political party in the world that I know about is either cracking apart or bleeding membership. The digital age hasn’t been kind to them. Do you believe they will make a comeback – or do you have some alternate vision of the politician in an online world? That’s something I would really love to hear from you about.

Liberty is empty. I think you make a terrific point, and one that is rarely dwelled on, when you emphasize the dynamism inspired by liberal democracy. Liberty stands at the start of this process. It promotes the emergence of amazing forms of personal and economic expression, from Lord of the Rings to Uber rides. But liberty is an emptiness, an absence of constraint that must be filled with something. That’s where virtue comes in. Without virtue, those emergent forms of expression would soon turn monstrous or decadent. Self-restraint and community-mindedness – virtue – are necessary preconditions to liberty.

If you agree with all of this, it follows that a moral education may be the most important aspect of preserving liberal democracy. How would you conduct such an education – and by whom? These are very large questions, I know…

There are many who believe that the individual is never virtuous – that the record of liberal democracy in the United States has been one of racism, injustice, and environmental degradation. I presume that you disagree with this attitude, but I don’t know that I have ever heard you say so explicitly. (I know where you stand on Trump!). Do you? More importantly, on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being total state control, where would you place the line between personal liberty and government mandate? The essay leaves this important question somewhat unclear.

Enough. Once again, thanks for getting my aging brain all cranked up – and I look forward to your response.

Dad

Hey Dad,

I’m glad you liked the essay, which certainly did not spring fully formed out of my brain, and which you and our conversations over the years have had no small impact on. Let me see if I can find some fodder to keep our family gatherings interesting in the usual Cuban way. You once described yourself as an “uncomplicated defender of our system of government.” Well, professional politicians and political parties are our system of government, in its most democratic part. There is hardly a liberal democracy on Earth which elects anyone other than professional politicians affiliated with political parties.

Parties have taken various forms since their rise to global dominance as the primary vehicle for organizing political office, a rise that began quite long ago. You say that they are bleeding membership, but you are really referring to voters who self-identify with the party in public polling or through some formal process which varies greatly by state and by country. Elected officials are still overwhelmingly members of parties; that has not changed one bit.

This is as true of countries with very low corruption and very competent administration as it is of countries that are run on the Boss Tweed principle at scale. It does not strike me as Platonic to observe that every liberal democracy—whether corrupt and poorly administered or honestly and competently administered—primarily elects career politicians who are members of parties. Rather, it seems more Platonic to insist that there is some universal logic to the professional politician which must lead, teleologically, to widespread graft and a spoils system, when this is at odds with history and experience.

Donald Trump is precisely an example of what goes wrong when weak parties allow amateurs to leapfrog their way into important offices. Our open primary system is quite unique, and greatly limits the ability of parties to pick their own candidates. I’m sure that his base did indeed see him as an answer to a crooked establishment, but in 2016 he mustered less than 45% of the votes in a primary contest in which roughly half of people who reliably vote Republican participated. The open primary system and the GOP’s inability to line up behind one candidate to oppose an outsider hijacking their party brand are what gave us Trump, more than any other specific cause.

But I don’t want to exaggerate our disagreement here, either. Adrian Rutt, who worked on the essay with me more than anyone, remarked that democracy as I presented it was far too one-sided. His complaint was that I left out how politicians could be leaders, or at any rate, how they could influence their constituents no less, and perhaps more, than the other way around. To that I would add that the relationship between citizens and government is not entirely or even mostly a matter of dutifully casting ballots once a year to throw the bums out.

Living in a liberal democracy means that all the tools of liberalism are available and widely used. People engage in private conversation, collegial public discussion, and intense partisan polemics, in order to persuade one another, to apply pressure to public officials, and to create windows of opportunity for political action. They associate in the form of activist groups, to be sure, but also in the form of churches and community groups and things that are not really meant to influence government or politics, but end up with the trust of their members—and therefore, with political muscle should they choose to flex them. In our system of single-member legislative districts, our representatives also spend the lion’s share of their time not engaging in legislative activity, but instead engaging in various constituency services. There is definitely a rich, thick, multidirectional relationship among officeholders and citizens.

This brings me, in a roundabout way, to both of your other two themes together; dignity but also the emptiness of liberty. When you ask me what the basis of dignity and the equal moral worth of persons is, I would say that it is not something that philosophy can really articulate or ground. We might call it an article of faith, and it is that in a way, but even that is perhaps too pithy. The truth is that in a liberal society we articulate the basis of dignity and equal moral worth all the time, in novels and in TV shows and in movies. There isn’t something like a scientific proof or a logical axiom that forms the basis of this belief; it’s something hazier and based in experience, lived and artistic.

When we move to answering what we should be doing with our liberty, or what the content of our education should be, my answer is much the same. I see the relative threadbare state of contemporary American civil society as an unfortunate state of affairs, and I judge it so primarily on the basis of history and stories told about the role that different voluntary organizations used to have in people’s lives at various points in the last two centuries.

Sociologists and historians have a tendency to make it sound all so functional, but it’s really about making meaningful lives and coming together as communities. Such moments where civil society really flowers are, to me, paragons of freedom of association at its very best, being used for the most desirable of ends. But again, I judge it so less on the basis of a philosophy than on the basis of stories, and the morality that undergirds them.

Liberty provides a space in which we can have these conversations about what a good life is and how to achieve, as well as the space to experiment with each. When enough people believe something like government provided education is an important part of how we should be promoting a set of values, democracy both provides them one avenue for achieving that, and also helps prevent particular parents and particular communities having their values steamrolled in the process.

A parting note on original sin narratives, of the sort you allude to about American history. I don’t mind original sin narratives, if they’re understood in their proper Augustinian sense. There’s a reason that my discussion of rule of law ended up centering more on studies of countries with large underground economies than on the work of legal theorists. I really think that when we get into a philosophical temper we are too quick to sanitize the bumbling, barely-functional mess that even the best human institutions look like on the inside.

By the same token, looking too closely at this mess too strongly tempts us to dismiss the possibility that institutions can ever be anything but a display of the absolute worst features of humanity. It seems obvious to me that American law is more reliable and more honored by both its citizens and its government than many parts of the world. We need to be able make observations of this kind without papering over the very real weaknesses and contradictions in the relatively better systems.

I think I will leave it at that for now; this has not been a brief reply! Sorry I did not get to all of your questions. But it’s always good to leave more to talk about.

Adam

Hey Adam,

Good stuff! I feel like I’ve already achieved my goal and now understand your thinking at a greater level of depth than before. So I could declare victory and withdraw with honor – but, of course, I won’t, because I’d like to add a couple of points. As you say, it’s that Cuban thing…

Without falling into the black hole of is versus ought, I have to say that just because most politicians in democracies today are professionals, it doesn’t follow that professionals are best for democracy. Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Wilson, Reagan, even Obama – many of our most consequential presidents were not in any sense professional politicians. Johnson and Nixon, who were, ended disastrously, and democracy isn’t doing so well under the current team of pros.

Still, I don’t believe what matters is this question of professionals or amateurs. What matters is the distance between rulers and ruled, which, under the principle of equality, should never be very great. And professional cliques invariably close ranks against outsiders and resist scrutiny or questioning.

Fortunately, it’s not an all-or-nothing proposition. If you want to avoid total amateurs like Trump, I suppose we should look for people who have been seasoned by the experience of life and work before entering politics. Most of the big names I listed above fall into that category.

With regards to liberty, I don’t recall ever having a conversation about the good life. I just married your mom, and that was the good life. Your grandparents, however, who loved each other just as much, lived in Cuba, where the lack of liberty and prevalence of state violence made our current troubles look like an episode of Duck Dynasty. Because tyranny destroys happiness as much as it does freedom, they had to escape to the US to recover the path to the good life.

The big objective, though, isn’t happiness. Forget Jefferson and the Declaration – happiness is only a byproduct. The objective, as you write, is to share “meaningful lives,” and I agree with you that these are oriented by the stories we tell ourselves. Every story of original sin, for example, must be matched by a story of redemption, or else we abandon the field to the nihilist and the barbarian. And I’m afraid that the old stories of meaning and salvation, including those that justify human dignity and equality, are gone with the wind. The consequent moral disorientation is reflected in our art and literature. I just watched a 2020 sci fi movie in which the human race was exterminated. It took for granted that we deserved it.

I remain, as you know, a short-term pessimist but a long-term optimist. I don’t have any special insight into the future. It’s an act of faith – you’re right about that too. I believe, without irony or qualifications, in the American people, which allows me to be an “uncomplicated defender” of liberal democracy. I also believe in you, your siblings, and your generation, whose task it will be to weave the stories that justify this strange and wonderful system to a new age – and most importantly, to embody those stories in your lives as a guide to those who come after. There will be crises and drama along the way. Take it from an old guy: there always are. But I have faith that you’ll get there.

Dad

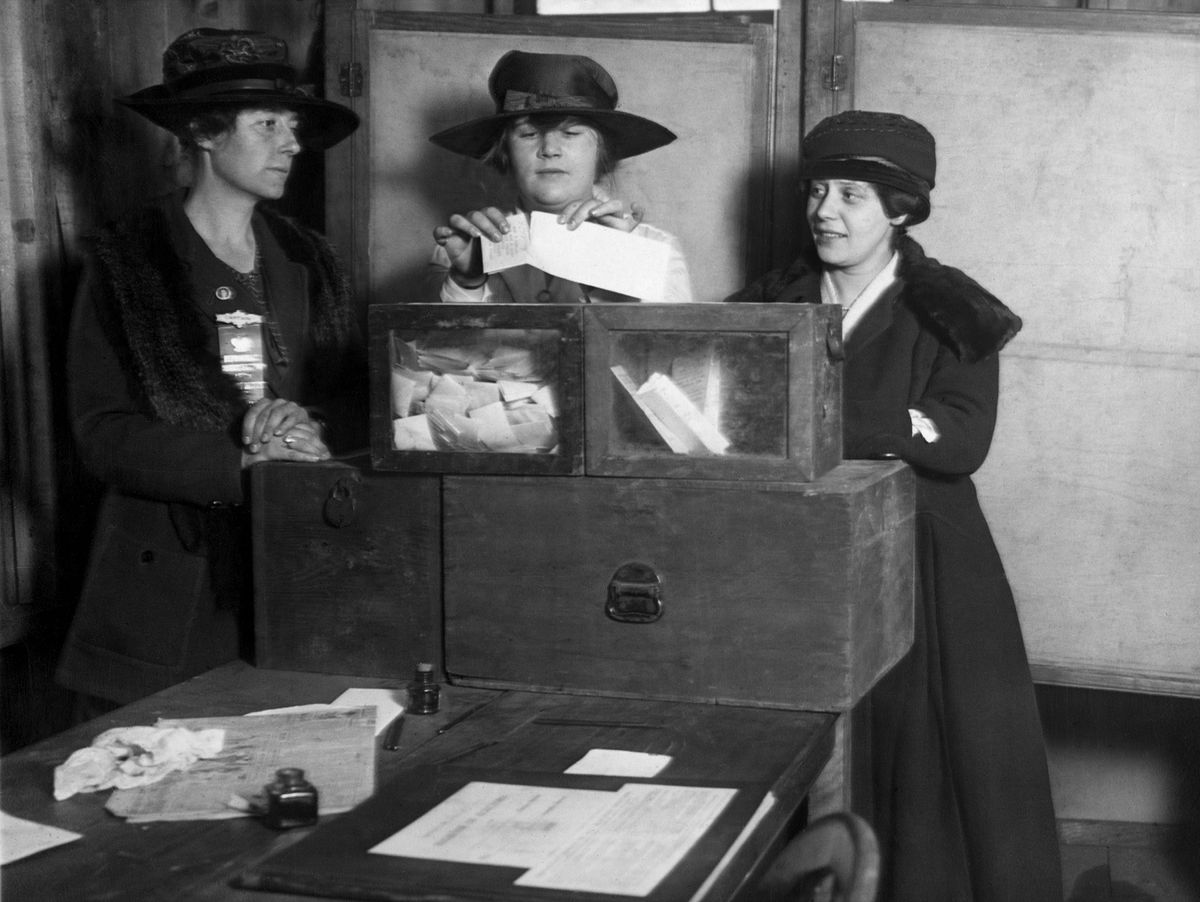

Featured image is Three suffragists casting votes in New York City