A Popular Front of Memory

As the right begins to revise their view of Hitler, we must revive the example Churchill set in that era.

In recent months, a curious trend has taken shape on the rightward edges of American discourse. As explicitly post-liberal thought gains ground in the intellectual circles on the right, we are also seeing a quiet attempt to recast the history of the Second World War. In a recent Atlantic piece, Yair Rosenberg documents this effort to soften Adolf Hitler’s historical reputation. Not as prominent, but no less telling, is the parallel attempt to cast Winston Churchill as the war’s true villain by figures like self-styled “historian” (and Tucker Carlson guest) Daryl Cooper.

Those invested in liberal memory have not rushed to Churchill’s defense. This is not entirely surprising. Churchill has long drawn criticism for his commitment to, and entanglement with, the British Empire. For some, these critiques have been grounds for distancing or even outright repudiation. And while none on the left would endorse any rehabilitation of fascism, many may still stop short of a wholehearted defense of Churchill.

More prosaically, he is British, so his place in American historical memory is often underrated on the left of center, especially since traditionally his most ardent American admirers have been on the right.This however misses the important role Churchill’s memory plays in the moral architecture of the 20th century. Churchill was not a pristine liberal hero—he was a human politician, with all the flaws and frailties that condition and profession entail. But if liberals forget Churchill, it opens the field for a broader contestation over the meaning of WWII.

In the world of conservative British politics of the 1930s and 40s, Churchill bats well above replacement level. Within his own party and social circle, sympathy for fascism was not unusual. Lord Lothian, a leading diplomatic figure, saw Hitler’s early aggression as a rational revision that ought to be accommodated. Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary and Churchill’s chief rival for leadership in 1940, favored negotiation even after the war had begun. Others, like Lord Rothermere, used their tabloid media empires to praise Hitler’s domestic order and denounce “Judaic influence.” These were not fringe actors. They were serious men of status and power, all seen—at different moments—as leaders in British conservatism. That Churchill saw Hitler clearly may seem unremarkable with hindsight (“of course Hitler was bad!”) but it was not obvious to many in his milieu and time.

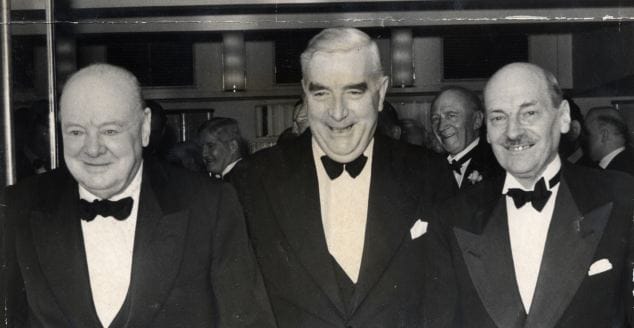

Churchill was also someone willing to adapt to the coalitional needs of the moment to defeat Hitler. This was true (and fraught) at the geopolitical level in his alliance with Stalin, but also domestically. His working relationship with Clement Attlee, the Labour leader, was one of real collaboration. Attlee served as Deputy Prime Minister, took on key responsibilities in the War Cabinet, and often stood in for Churchill in Parliament. The two men disagreed sharply on domestic policy, and the election of 1945, held just weeks after victory in Europe, saw the two wartime partners face off in a surprisingly vicious contest. But during the war Churchill did more than just give rhetorical lip service to a united front.

Churchill’s post premiership wasn’t idle though. His “Iron Curtain speech” in Fulton, Missouri framed the stakes of the Cold War. Unsurprisingly, this also helped cement a longstanding admiration of Churchill on the American right. Decades later, Hillsdale College hosts a hub focused on Churchill scholarship and Hillsdale’s president Larry Arn is noted as a longtime Churchill admirer. He was seen as a patron saint of trans-Atlanticism and a vigorous (at times combative) foreign policy stance. [1]

This admiration is good if it encompasses the totality of his legacy. Churchill provides center-right liberals with a usable role model who championed freedom, democratic governance, and rule of law over authoritarianism. And in an environment where the right is tempted by a darker vision, that model is important. For the left, he offers a concrete example of what it looks like to join forces with those on the right to oppose authoritarianism. If the left today is not willing to acknowledge Churchill’s contributions, do they really have what it takes to find allies and muster opposition to contemporary authoritarianism?There is a trope familiar in fantasy stories. An ancient evil is defeated and sealed away, only to re-emerge long after its horrors are forgotten. Churchill’s memory is that seal.

You cannot admire Churchill and rehabilitate Hitler. The two stand on opposite sides of the story. That is why, for the revisionist right, tearing down Churchill is a necessary precondition for lifting up Hitler. It’s also why liberals should resist it. Remembering Churchill keeps the seals in place that lock away a great evil. Churchill is not a saint but his contribution is real. Intellectuals are prone to discount the role of politicians because the ideas that politicians bring to the table are often not novel or even always coherent. Politicians live in a world of trade offs, compromise, and the art of the possible. But, as a practical matter, in the 1940s, Churchill rallied a broad front against fascism. He set the table for the postwar liberal settlement. He even, in the fight against fascism, made choices that would doom the future viability of his beloved British Empire. If liberals don’t tend to his memory, they leave the field of WWII memory open for more insidious revisionist weeds.

[1] It is worth noting that his role in creating the transatlantic world, and opposition to Soviet communism (both before and after the war) ensured he received the role of villain in much Russian historiography of the Second World War. Indeed, for example, a Russian nationalist outlet explicitly pointed to trying to reverse the logic of Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech - in 2024.

Featured image is Churchill, Australian Prime Minister Bob Menzies, and Attlee, 1940s.