Abundance and Labor Unions

Strong labor unions are not at odds with a society that builds.

Earlier this summer at WelcomeFest, apparently the hottest, most moderate-est political conference in town, there was a fireside moderated by Josh Barro of the Very Serious Substack with Congressman Ritchie Torres (D-NY). The conversation was primarily about abundance and how to increase the supply of critical goods like healthcare and housing. But halfway through, both Barro and Congressman Torres started to talk about why New York City was underperforming politically in the first place and the role of unions came up.

“When I look at policies in New York that stand in the way of abundance, very often if you look under the hood, you eventually find a labor union at the end that's the driver,” said Barro.

Barro isn’t the only one mad at unions.

Gary Winslett, an associate professor at Middlebury College, Senior Advisor at the Chamber of Progress, and writer of the Substack The Rebuild, argues that one of the many reasons manufacturing jobs have left the unionized Midwest is that the business environment in the South is better due to right-to-work laws, which makes the South more competitive by disincentivizing unionization and reducing labor costs.

Across multiple issues, Democrats and other politicians of all stripes have found something to be mad at unions about. They’re mad at the teacher’s unions who led the school closures that are causing persistent learning gaps among children to this very day. They’re pissed at dockworkers over their opposition to port automation, which would help reduce our unusually high shipping costs and get us aligned with port systems in the rest of the world. And they’ve even pointed the finger at unions for the less-than-stellar implementation of the Biden Administration’s various infrastructure bills, whose reliance on union labor made it more difficult to deliver the infrastructure it promised.

So in short, labor unions have become a bit of a punching bag for abundance thinkers. While no one accuses them of being the only cause for why it’s so hard to “build” effectively and efficiently, many argue that the union as an institution is inherently opposed to a society that builds.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Labor unions exist in many forms with many functions. The current state of labor in America is a function of policy choices and historical conditions that have led it to emphasize adversarialism, aka an “Exit” model, over more pluralistic, cooperative forms of engagement, the “Voice” model. With the right policies, unions can go from blockers to builders.

Abundance policies and union activities are complements, not substitutes. Letting each focus on a different, but equally valid goal (government policy on growth; unions on the distribution of that growth) can help push for an across-the-board progressive agenda that gets everyone involved in building.

The working class is slipping away

Any conversation about politics and policy must reckon with the fact that the working class now regularly votes for conservative parties. Look at the last four Presidential elections alone and you can see that the Democratic Party has had a consistent declining share of the non-college educated vote, going from 51% in 2012 to 43% in 2024. This trend holds for both the white and the non-white working class. Any political strategy worth its while has to address this decline; the working class is too massive to ignore.

In the age of distrust where most institutions are unpopular, unions still enjoy favorable support from the public. Unions have about 70% favorability, which puts its favorability higher than most political institutions today.

One basic truism is that using an unpopular institution to attack a more popular one is risky because people will rally around the institution they already like. To say that public policy should operate against the interests of unions is to say that Congress, the Administration, and various state governments should be the actors that do so. What do you think their current favorability is?

So as a starting point, even before we get to policy, we have to recognize the battlefield for what it is. Governmental institutions on their own are very, very unpopular and that is unlikely to change in the near future. Building a coalition around abundance will mean bringing in more popular allies into the fold, including unions.

What do unions do

Think of a union as a talent agent for the workers it represents. For a particular workplace, a union negotiates a “collective-bargaining agreement” (CBA), a contract, with the employer on behalf of the workers. These contracts set the key components of employment, including wages, benefits, and various working conditions such as disciplinary processes/workplace protections, hiring and firing practices, job performance expectations, etc.

If workers are interested in joining the union, they can collect signatures from their co-workers to schedule a union election. Once a majority of the workers vote to be in a union, it can officially represent them and push to negotiate a CBA on their behalf. The unions’ new members will both elect the leadership of the union and ultimately be the ones to ratify a proposed collective bargaining agreement. They will also of course pay membership dues so that the union can maintain its operations.

The specific feature to note here is that American labor law centers around “exclusive unionism”: once a workplace votes to unionize, the union will negotiate the contract for all workers in this place, including the ones that voted against it or join the company later at a later date.

Finally, if workers are in between collective bargaining agreements, meaning one has expired and they have not successfully negotiated a new one, they can vote to go on strike and effectively stop or significantly weaken the ability of the company to function. This is typically a bargaining tactic deployed by unions to get a good agreement.

So what does this mean for the abundance agenda?

Are unions inherently anti-abundance?

It’s worth noting upfront that much of the above is not inherently anti-abundance. The act of collective bargaining itself simply means that workers band together to negotiate aggressively to get the best deal possible. No one would say professional athletes or superstar CEO’s, for example, are in the wrong for playing hardball to get a good deal.

The two most common arguments that labor unions cause stagnation are that they 1) wield political power to lobby for anti-abundance policies and 2) are anti-competitive; benefiting their members by shielding them from competition. It is interesting to note here that these arguments against unions are the same ones in principle wielded by proponents of progressive anti-trust: that “bigness”, or concentration, is inherently bad for democracy and power.

In a follow-up post to his fireside, Barro highlights specific examples in New York City of unions blocking abundance policies:

- A law that requires special permits to build new hotels, thus reducing hotel development and benefit existing, unionized hotels.

- A law that provides subsidies to construction firms if they pay higher wages or use unionized labor.

- A collective bargaining agreement that effectively requires subways to hire more people than they need to do the work.

Off the bat, two of the above do not come from union activities themselves, but laws passed that happen to benefit union members as well. To be sure, many unions do lobby for “scarcity” policies: policies that deprioritize growth and innovation in favor of getting “our share” on what’s out there before other’s can get theirs. Both progressive and conservative-friendly union leaders alike supported the recent tariffs, despite that in the long-run they will hurt the very industries they are intended to help.

But this thinking penalizes unions for a universal sin: special interest groups are everywhere. Companies are always begging for special privileges such as subsidies and regulations that raise the cost of entry for new competitors. Sure, that law requiring excessive hotel permitting helps hotel workers’ unions; but it obviously helps the existing hotel industry as well. A law that benefits construction firms with higher labor costs not only shields construction unions from competition, but the firms themselves as well. Outside these specific examples, the bogeymen that block the development of new housing are often private civil-society groups including homeowner associations and other more informal groupings; entities that ultimately exist in a society that recognizes free association between private individuals. It does not make sense to attack the existence and function of unions for engaging in an ancillary activity that every other economic entity engages in. The real enemy here is the use of the law, an inherently coercive instrument, for special privileges.

That said, the idea that unions are anti-abundance is grounded in a partial truth: unions can sometimes bargain in ways that lock-in and even reward inefficiency. The subways example is a fair example of this as were teacher-led school closures that helped increase student underperformance.

The problem though is that this presumes there’s only one possible way for unions to exist and behave. As with any other institution, union structures are not destiny—the nature of unions has varied both in U.S. history and around the world. We should look to examples elsewhere to see if a better way is possible.

Alternatives are possible

At the root of all this is that the union movement for historical reasons is very different in America than it is anywhere else.

You can think of the ways unions work using Albert O. Hirschman’s Exit-Voice-Loyalty model, which shows how members of an organization pursue both their own interests and the interests of the organization. A person exercises the power of “Exit” by finding ways to walk away from their organization; finding both better options for themselves and putting pressure on the organization to improve things. People exercise the power of “Voice” in more democratized organizations by having a direct say in key decision-making processes.

Unions in America are an odd fit because much of American economic policy is centered around exercising “Exit,” which does not neatly fit with the union model. This attempt to organize the union model along Exit-centric lines incentivizes unions to operate in a much more anti-abundance framework.

Our unions focus on “Exit” in two ways: by restricting the exit of the other side, the company, through collective bargaining agreements that mandate reliance on the union and by holding threat of labor strikes over them that make it harder to replace union workers in between agreements. Other countries have more harmonious industrial relations for a few reasons.

First, as a broader point, the more unionized an industry is, the more the union becomes a force for the general interest not special interests. You can think of a highly-unionized industry as the unionized workers having an equity stake in the industry itself. By representing more workers, it has more skin in the game and its actions can directly tank or benefit the industry as a whole. When the industry is thriving, they stand to benefit from a share of those gains as well. Alternatively, a union that represents a small number of workers in an industry is less invested in the long-term growth and productivity of that industry. The problem with small unions is that they can benefit by imposing the costs on someone else. Bigger unions have fewer opportunities to do that.

Second, the institutional design of labor union matters, much like it would for any other organization. No one assumes all companies in an industry act the same by virtue of being the same type of legal entity, their inner workings, culture, etc. all matter.

Unions in Western and Northern Europe differ by emphasizing action through “Voice.” They bargain across the entire industry, instead of workplace by workplace, which means they are able to exercise input into the future of the industry. Unions in many of these countries can also develop work councils at the workplace level that have direct control over workplace conditions as well as seats on company boards so they can take part in the highest level of oversight.

A better policy framework for unions in America would be to effectively de-regulate unions and let them pursue action not just through the “Exit” channel, but through “Voice” channels as well.

One problem is that American unions bargain at the enterprise-level, trying to strike deals from workplace to workplace. We should consider legislation that makes it easier to bargain sectorally, giving workers a greater reason to join unions and giving unions a greater incentive to invest in the future of the industry they operate in. Sectoral-bargaining helps makes it so that a union acts more like a principal of an industry than just an agent.

Another issue is that American unions are also legally restricted from cooperating with employers and find more productive forms of engagement, such as managing benefits as they do in Belgium or forming work councils like in Germany. These restrictions in the National Labor Relations Act should be modified so that unions have the option to engage in more cooperative behavior as well.

American unions also by law exclude managerial employees, pitting their interests against other workers. But most managers are not owners, they are effectively workers whose work involves optimizing the time of others in much the same way an engineer may optimize machinery. In the Nordic countries, managers are able to participate in their own unions as well. Removing the restriction on managers would both expand the pool of unionized labor in an industry and also reduce adversarialism between different groups of people in a particular company.

Finally, when a workplace votes to organize, they must be part of the one union that organized the election. This ties the hands of both the workers and the union. The union must represent everybody, including people who did not want to join in the first place. In right-to-work states, this includes people who can refuse to pay dues as well. Likewise, the workers themselves can only join the union that organized the election. If they want to join a different union, they would have to engage in a new election at a designated point in the future to decertify the existing one and elect a new one. One policy option to fix this issue is Minority Unionism, which would be permitting workers in a workplace to belong to different unions more in line with their interests. This could be done by having the union election be less about joining a specific union and more the right to join and be represented by the union of one’s choosing.

Coupling the ability to do both minority unionism and sectoral bargaining gets you both scale and competition. If unions underperform in their duties to their members, an outside union can step in and take their members. Likewise, unions that prove unusually competent and successful can grow beyond their current bounds, picking up members across multiple companies in a sector to negotiate in a more coordinated way.

An America where unions can 1) bargain sectorally, 2) cooperate with employers directly to provide services like benefits management, 3) account for managerial employees interests, and 4) have a plurality of options is one where union activities are abundance-aligned.

Each of these components reduces the incentive for unions to act by lock-out competition or reduce productivity. Most workers want their unions to adopt a more cooperative stance, which coupled with the ability to cooperate, means they are more likely to account for owner preferences. Spending resources instead on delivering benefits like unemployment insurance means less time spent in adversarial bargaining. Including managers in the union means accounting for the management team’s preference for efficiency.

In fact, a plural union model could theroetically permit abundance activists to organize “abundance unions”: organizations that prioritize demanding better and more investment and upskilling from the owners as well as more flexible benefit packages. If we believe that this is an agenda that people, especially the working majority truly want, then we should be able to persuade people to join organizations united in this purpose.

This approach couples well with abundance policies from the government. It would allow one to follow the Tinbergen Rule (at least policy each dedicated to one goal) - the use of governmental policy (including deregulations) could focus on abundance while unions focus on shared prosperity.

Bringing unions under the abundance umbrella

If you are still concerned about unions as a lobbying force, there’s a few additional reforms to consider.

The concern about lobbying is rooted in the issue that it is too easy for the law to be weaponized as a veto against action. One promising way to address that is to develop new legal principles for the judiciary to weaken such vetoes. Some legal thinkers are developing a “law of abundance” which argues that judges should interpret the law in a way that factors in abundance consideration.

In addition, the best way to address issues of political influence is with laws that apply to everyone equally. We should consider reforms in lobbying and political spending that would apply to all organizations regardless of their purpose: unions, corporations, small businesses, and non-profits alike.

Work together, not against each other

A better working relationship between the Abundance movement and labor unions is a way to have one’s cake and eat it too. All political ideologies are at least partially about priorities: saying what issues matter more than others. For Abundance thought, that means prioritizing public policies that prioritize growth and efficiency over equality and power. Labor unions, structured properly, can help fill the gap. It’s time to build and with unions on our side, we can ensure we do it the right way.

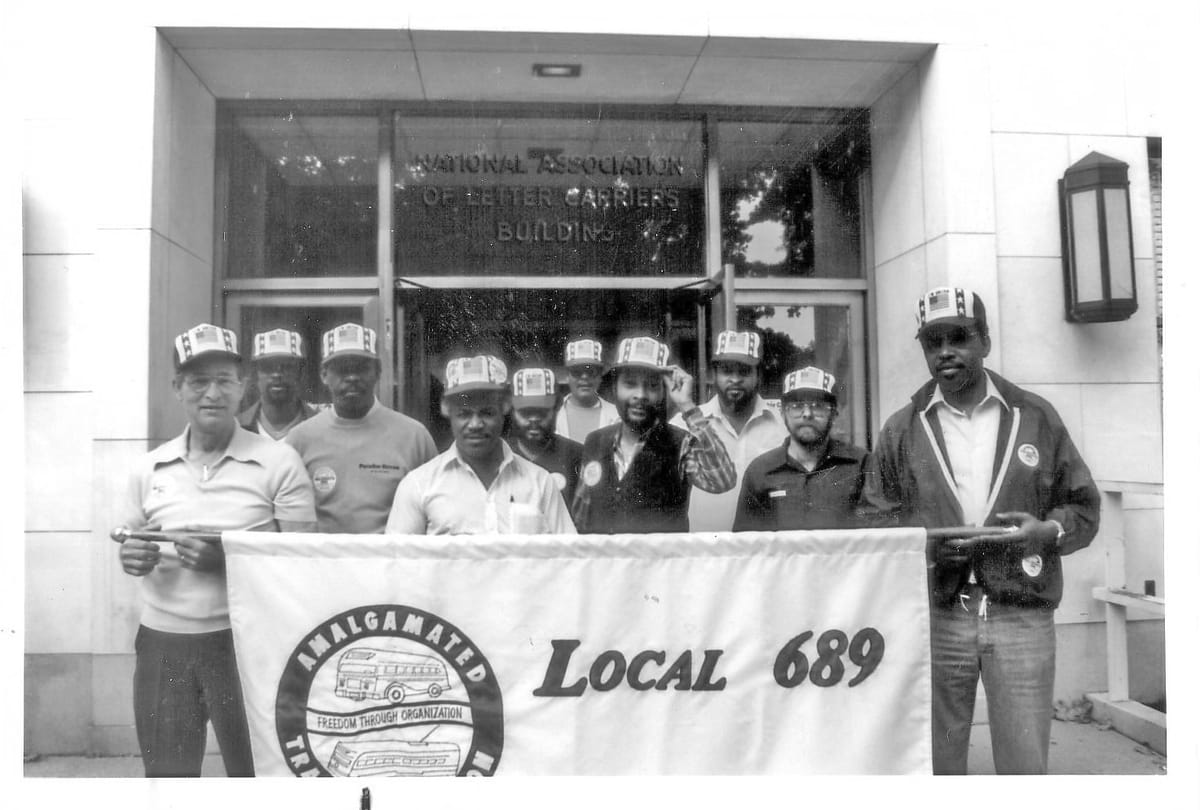

Featured image D.C. transit union poses before joining Solidarity Day in 1981, by John A. Thomas