Article II as Suicide Pact

Justice Robert Jackson's fear that "doctrinaire logic" could turn the Constitution into a "suicide pact" was warranted, but the Bill of Rights is not the problem.

In 1949, Justice Robert Jackson warned that “doctrinaire logic” by the Supreme Court would “convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.” In that case, Terminiello v. Chicago, the Supreme Court reversed the conviction of Arthur Terminiello. Terminiello was a suspended Catholic priest and a rabid antisemite who was convicted of violating a Chicago ordinance against “breach of peace.”

Justice Jackson had served in Franklin Roosevelt’s Department of Justice and, most famously, served as chief prosecutor at the Nuremburg Trials. There’s little doubt that his exposure to fascism, as well as the chaos that led to Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, influenced Jackson’s dissenting opinion in Terminiello.

The phrase, “the Constitution is not a suicide pact” is perhaps trite. It is often attributed to Abraham Lincoln as justification for his aggressive use of executive power during the Civil War. But the phrase has stuck. Indeed, a prominent federal judge wrote a book with the same title. That book, written by Richard Posner in the wake of 9/11, argued that civil liberties must be balanced against the maintenance of national security. Posner shared Justice Jackson’s concern with “doctrinaire logic,” but attributed a proclivity for that logic to both civil libertarians and government officials.

Ironically, Jackson’s warning to the majority in Terminiello has proved prescient, as the Roberts Court has interpreted the Constitution to enshrine vast, indeed royal, prerogatives into Article II. As a result, the Court has aggrandized its own power as well as that of the president. And the end result is that it is Article II, rather than the Bill of Rights, that has become a suicide pact.

This is a complicated set of developments. Samantha Hancox-Li has focused, in part, on the institutional atrophy of Congress in the 1990s as the starting point for our current political moment. A “heyday” of Congress is engrained in the American historical imagination—after all, Congress gave us the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and many others. To be sure, scholars have taken issue with this perception of Congress. But the Supreme Court has played just as large a role in setting the stage for our current crisis.

Executive (and judicial) aggrandizement

Over the past decade, give or take, the Supreme Court has taken on the role of enabler. In a series of cases concerning executive power, the Court has inferred a broad swath of prerogatives into the text of Article II. These decisions have the practical effect of aggrandizing the power of both the courts and the president.

In Seila Law v. CFPB, the Court struck down the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The director of the CFPB was protected from at-will removal by the president. Relying on the theory of presidential representation, the Court asserted that the president is “the most democratic and politically accountable official in Government.” Never mind that this statement ignores the way presidents are actually selected in this country, by a method enshrined in the Constitution that makes it possible for a candidate to win despite receiving fewer votes.

According to the Court’s logic in Seila Law, because the president is the most “accountable” official in the federal government, they must be able to fire people who exercise executive power on behalf of the United States. This is a “bracingly simple idea.” It’s an idea rooted in a normative theory of American democracy; what American democracy requires. A year after Seila Law, the Court struck down the statutory structure of the Federal Housing Finance Agency for the same reason it struck down the CFPB.

Finally, in Trump v. United States, the Court extended absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for presidents’ “official acts.” The majority opinion is, to put it lightly, a mess. The Court gave little-to-no indication of what constitutes “official acts”, or how immunity would operate at the margins. Of note for this essay, the majority opinion’s primary concern is that of encroachment on the president’s power. The threat of criminal prosecution, lamented John Roberts, presents a “counterproductive burden[]” on the “vigor” and “energy” of the president.

Taken together, the Court’s presidential removal power jurisprudence embraces a distinct view of American democracy: presidentialist democracy. Implicit in the Court’s decisions is a vision of a statesman-like, virtuous chief executive who takes seriously the duty to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” Of course, this vision of the institutional presidency assumes that whoever the president is, they will act in the best interests of the country and, well, follow the law—whether it be federal statutes, court rulings, or the Constitution itself.

The Roberts Court’s jurisprudence has cleared the way for the presidency to aggrandize its powers. It has done so by denigrating the power of Congress to structure the government by law and thereby check presidential overreach. Looming in the background is the “resurgence” of Congress that occurred in the aftermath of Watergate, where Congress enacted new federal statutes that provided mechanisms to oversee the executive branch. It’s clear that a majority of the Roberts Court sees that resurgence as a grave mistake, never to be repeated again. A second consequence is that the Supreme Court comes away with more power. Take for example Trump v. U.S. and immunity for “official acts.” Under this framework, it is largely up to the courts to determine what an “official” act is. The final answer to that question is to be ultimately decided by the Supreme Court.

Reaping what the Supreme Court sowed

During his first term, Trump famously said “I have an Article II, where I have the right to do whatever I want as president.” If the first three months has shown us anything, it’s that Trump truly believes that assertion to be true.

Three months into his second term, Trump has attempted to end birthright citizenship, gut the capacity of government agencies, kidnap and summarily deport members of disfavored groups, withhold federal funding from universities, intimidate and punish law firms that represent clients or causes that Trump dislikes, and coerce states into adopting more restrictive voting laws. Moreover, Trump has undertaken these initiatives without congressional authorization, and often in violation of federal law and the Constitution. Federal courts across the country have enjoined many of Trump’s executive orders, but the administration has begun defying court orders.

It is clear that Trump feels emboldened by the Roberts Court’s executive power jurisprudence. The Attorney General of the United States has openly defied the Court’s order to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a man wrongfully deported to a prison in El Salvador. Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff and Homeland Security advisor, has referred to judges as “communists” who want to keep “terrorists” in the United States. Elon Musk, the leader of DOGE, openly advocated impeaching judges who ruled against the Trump administration, denouncing them as “activist judges” on X.

Again, Trump has governed exclusively by executive order. These orders directly contravene federal law and the Constitution. It is on these bases that federal judges have prevented the orders from being implemented.

Article II as a suicide pact

The Supreme Court’s enabling of presidential aggrandizement has made Article II of the Constitution into a suicide pact. The Court’s normative arguments for accountability have, unsurprisingly, led to less accountability in government.

Trump’s defiance of these court orders represents an existential threat to the rule of law and the very democratic accountability that the unitary executive rests on. It’s a truism that the courts have to rely on the executive branch to enforce their decisions in good faith. But Trump appears prepared to violate that norm. The Court’s self-aggrandizement appears to be returning to haunt them.

The Roberts Court’s “doctrinaire” separation of powers formalism has created a monster. Trump is a president “unbound,” one who feels no obligation to follow the law or democratic norms.

The idea that the president should follow the law has seemed intuitive. President Truman obeyed the Court’s decision in the “Steel Seizure Case” despite vehement disagreement. President Eisenhower deployed federal troops to Arkansas to enforce Brown v. Board of Education. President Biden obeyed the Court when it struck down his student loan forgiveness plan.

Donald Trump does not share this devotion to the rule of law. If the president is unbounded by law, the status of constitutional democracy rests on shaky footing. The tragedy is that the Supreme Court laid the foundation for the suicide pact, one that Trump intends to see through.

Support Opposition Media

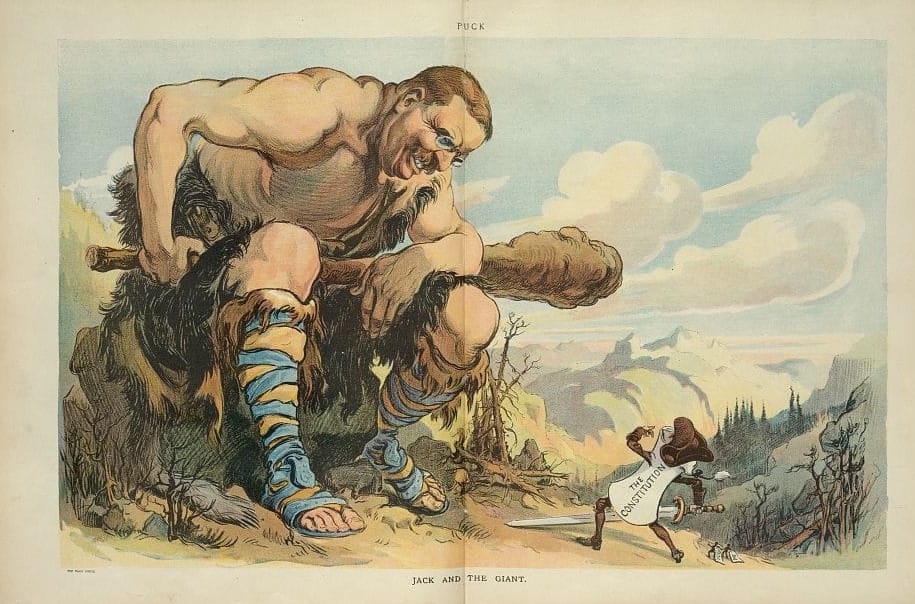

Featured image is Jack and the giant, by Udo Keppler