Can We Afford Freedom of Press in a Pandemic?

A divided America has come together in the face of a crisis; to a man they have all agreed that “if the world were organised according to my political views, this tragedy would never have happened.” For a certain class of American, this includes their views on how the media ought to be organized. This class has ceaselessly told whoever would listen that the media we had before the Internet was superior in every way. It was fact based, dispassionate, and nonpartisan. Above all, it was authoritative—you could trust it. If only we had that system to help us through this crisis! Some go even further, looking to our contemporaries in China for a solution to what ails us.

I will endeavor to evaluate the performance of the American media—including blogs and social media—during the first three months of the year, as COVID-19 began its relentless, exponential spread. But it always pays to begin by asking: compared to what? So I want to make it clear up front: I do not believe there has ever been a media system that has performed better than ours in situations like this. Meanwhile, the Chinese censors bear more culpability for allowing the virus to spread to the world than any other single party; having ordered doctors to suppress information, sent police to threaten them when they did not, and erased the public outcry when these reckless actions came out. Nostalgia for the mass media of yesteryear is misguided, if understandable. Yearning for the firm hand of authoritarianism, at just the moment that those authoritarians have put the entire world at risk, is inexcusable.

Evaluation requires a standard, and if I have learned anything during this pandemic, it is that what appears a reasonable standard today can age very poorly in a matter of days or even hours. I will be proceeding on the assumption that calling for mitigation efforts was the right thing to be doing, and the earlier this call was made, the better it looks in hindsight. Drawing early attention to now-familiar details, such as the existence of asymptomatic transmission, will be considered especially praiseworthy. On the other side, those outlets that went out of their way to minimize the risks do not look good in hindsight. That is the basic perspective I will bring to this process.

In general, the professional media did better than its critics give it credit for. When it came to evaluating the crisis, the worst that can be said for many journalists is that they simply reflected the views of an expert community which itself fared poorly well into February. Many of the common vices of journalism were on display, of course, in headlines and social media promotional posts making bold declarations that there would be no pandemic, even when the article itself was more nuanced. And the tendency to use COVID-19 as a vehicle for grinding highly templated ideological axes was endemic.

But within the six week period between when the WHO declared a global health emergency and the Santa Clara County Health Department initiated Bay Area “shelter-in-place” orders, the bulk of the media had come around. A coverage delay of weeks before converging on a more or less accurate picture is not an unreasonable standard in almost any other situation, especially when there is at least a substantial minority of coverage from the outset that is getting it right. Compare this to with the 1918 Spanish Flu, where a wartime media blackout combined with a patchy local news system so that the full story was never truly told throughout the outbreak. Or the 1968 flu, in which the midcentury media struck a “business as usual” tone as the death toll mounted to 100,000. Or most importantly, compare to the Chinese media’s shameful performance in December and January, or in the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Six weeks turned out, for COVID-19, to be not nearly fast enough—we could have taken measures in January or February for “pennies” that would have effectively curbed the spread, but by mid-March it was far too late. But contrary to its critics, the openness of our information sphere is its great strength, not its great weakness. All other historical and contemporary alternatives make this obvious. In the age of Internet-connected devices, no one actor can stop a message from getting out. How fast the message spreads is another question—choices made by the big outlets can slow its spread or create confusion, meaning that the practices adopted by those outlets do matter. Moreover, other competing messages reaching both small and large audiences will be generated and proliferate in tandem. There is no guarantee that the best messages will become prominent; it is an empirical question, to be taken case by case. Bad messages and bad actors, even very small scale ones, benefit from the same potential to go viral. But there is a guarantee that you won’t end up with a single or even a handful of decision makers who can simply veto the best messages from being told by anyone at all to anyone else.

The ecosystem

Large, open networks create skewed audience distributions, or as Clay Shirky put it, “freedom of choice makes stars inevitable.” Still, skew does not mean stasis, which is precisely what the authoritarian media model requires. During this pandemic, a March 10 Medium article urging social distancing written by tech executive Tomas Pueyo was viewed over 40 million times. At the time Pueyo had a little over 6,500 followers on Twitter and, we can safely presume, had never before enjoyed an audience remotely the size of what his viral article found. He did not have to ask anyone’s permission; Medium is a glorified blog platform, a LiveJournal or a Tumblr with aspirations of respectability. He did his research, which he cited meticulously, created a score of graphs, wrote up his piece, and hit “publish”. Within a week it had been viewed tens of millions of times.

If that example is not to your taste, consider STAT News, a young outlet covering the health industry which employs around 30 veteran health and science reporters. It was on top of COVID-19 from day one, and were early on a number of crucial details. They covered asymptomatic transmission as early as January 22nd, describing cases of transmission where patients were “experiencing only very mild symptoms or possibly without experiencing symptoms at all.” According to The New York Times:

The site has attracted nearly 30 million unique visitors this year, which is four to five times more traffic than usual, said Rick Berke, the executive editor, who oversees the editorial and business departments.

STAT News deserves the success its world-class COVID-19 coverage has brought it, but it is not much like the typical winner of the messy, freewheeling struggle for attention in the information sphere. Articles like Pueyo’s, in which an amateur invests in a great deal of research are more common, though not exactly the norm, either. The typical blog post, social media update, or even professional media article is much less rigorous and authored by individuals lacking in subject matter expertise.

Still, the openness of our system has allowed people to publicly sound the alarm who would not have had a platform in less open or more tightly controlled alternatives. Individuals with thousands or tens of thousands of followers on Twitter sounded the alarm in January about everything from ventilator shortages to the expected economic fallout of COVID-19 having “transmission characteristics similar to the common cold.” One individual with over a hundred thousand followers was emphasizing just how quickly an exponentially growing virus could spread. Public intellectual Nassim Taleb called out the possibility of a pandemic on January 26. Prepper Jon Stokes provided a guide for how to prepare for a lockdown in response to COVID-19 on February 6th.

In the conservative corner of the ecosystem, a group dubbed “Trump’s early adopters” by Vanity Fair and “conspiracy theorists” by Mother Jones, which includes Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams, fringe reactionary Mike Cernovich, and the former Breitbart executive chairman and Trump administration official Steve Bannon, were all sounding the alarm early. Claire Lehmann, editor-in-chief of the conservative-adjacent outlet Quillette, wrote a piece on March 3rd on the “Once-in-a-Century Pathogen” which was right on the mark and covered many important topics, including asymptomatic transmission.

These individuals and others like them had fairly niche audiences, nothing like the big outlets or even a STAT News. But as Pueyo’s article demonstrates, today’s audience distribution dramatically underestimates potential reach. Let us conservatively estimate that every private individual or small publication with the best early COVID-19 messages across the entire information sphere was able to reach a cumulative audience of only one million, a small fraction of the population. To begin with, that is one million people more that received the right messages early than would have in a closed system.

The logic of exponential spread that has allowed the literal virus to ravage the world also governs the spread of content that “goes viral”. An audience of a dozen can quickly become an audience of hundreds, which can quickly become an audience of thousands. An audience of one million? That can become an audience of one hundred million in the blink of an eye. Taking your social media messages seriously might be mocked as “hashtag activism,” but the fact is that anyone has a potential reach of millions when posting publicly. The cumulative efforts of private individuals like Pueyo, alongside mid-tier publications like STAT News, vastly improve the quality of the information sphere.

The experts

Consider the following quotes:

Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission

We (…) don’t have any clear evidence of patients being infectious before symptom on sets.

Broadly-applied interventions such as travel bans can cause public panic, impede individual rights, lead to secondary effects like shortages of food, and may not be effective at containing a virus if it has already spread outside of the epicenter, as nCoV-2019 has done.

The risk of acquiring a respiratory infection through air travel is still extraordinarily low,

Roses are red/Violets are blue/Risk is low for #coronavirus/But high for the #flu

“The chances are astonishingly low that you would come into contact in a coronavirus infection” at work or in a public setting

Right now, at this moment, there’s no need to change anything that you’re doing on a day by day basis.

Who said it? Many were quoted in the media. But every single one comes from either an expert or a public health institution.

It was the WHO that announced on January 14 that there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” It was the CDC who, on January 27—the day after the Chinese Health Minister had announced that they had observed cases of transmission during the incubation period—stated that there wasn’t “any clear evidence of patients being infectious before symptom on sets”. Rebecca Katz, Director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown, was quoted in Buzzfeed downplaying the effectiveness of “Broadly-applied interventions” on January 28th, six days after the lockdown of Wuhan had begun. Isaac Bogoch, “a professor at the University of Toronto who studies how air travel influences the dynamics of outbreaks,” was calling the risk of contracting a respiratory disease while flying “extraordinarily low” in a January 31 Vox article. Surgeon General Jerome Adams tweeted his poem on February 1, two days after WHO declared a global health emergency. Next is Dr. Stanley Deresinski, an infectious disease physician at Stanford Health Care, quoted in the infamous February 13 Recode article on Silicon Valley’s cautiousness. After that is Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of NIAID and member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, on February 29.

These were not the assertions of journalists. Only some were the assertions of institutional public health officials, who can only maintain their positions by carefully considering their political context when making public statements. Three of those quoted were simply experts on the relevant subject. And this pattern was representative of many of the pieces I reviewed, even those portrayed after the fact as examples of journalists falling down on the job. The Recode article is a case in point, and has been frequently pointed to as a particularly egregious case of journalistic malpractice.

The point of that article was to mock Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs and venture capitalists for having a “deep, paranoid fear about bodies and disease.” The temptation to use COVID-19 coverage as a vehicle for attacking old antagonists and repeating old arguments proved difficult to resist on every medium. But the important point here is that the Recode article did not assert anything about the risks of the outbreak on its author’s own authority. From the beginning of the article, the framing is:

Public health officials in the area have said there’s currently a low risk to public health; the cases, they say, have been contained to those who have recently traveled to Wuhan and their direct family members.

The person who downplays handshakes as a mechanism for transmission is not author Shirin Ghaffary, but Dr. Stanley Deresinski, an infectious disease physician at Stanford Health Care.

Ghaffary’s own ignorance, and by extension that of her editor, is put on display in her framing of Google’s decision to have all employees in China work from home. She quoted an anonymous employee comparing Google employees in Beijing working from home because of an outbreak in Wuhan to employees in Chicago doing the same because of an outbreak in New York. The implication is that Google made a rash decision in panic, but given the dense network of travel between Chicago and New York every day, such a policy would make perfect sense.

But in terms of her evaluation of the risks of COVID-19 and what ought to be done about it, the author mostly reflected the positions of public health institutions and public health experts. She was not alone in this. Deference to experts and authorities was the rule among professional media.

STAT News, the outlet that was the earliest and best in its coverage, corroborates this: they argued that expert failure played a critical role in allowing the outbreak to become a pandemic:

As China was seeking to rid itself of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a number of leading infectious diseases scientists mused that the outbreak would be controlled or might burn itself out. (…)The virus, the thinking went, didn’t appear to be behaving as explosively outside of China as it had inside it.

“Everybody was in denial of this coming, including the U.S. And everybody got hit — just as simple as that,” Gary Kobinger, director of the Infectious Disease Research Center at Laval University in Quebec, told STAT.

Kobinger himself thought the WHO’s immediate move to a war footing on the virus — the day after China made its first official report on it on Dec. 31 — was probably an overreaction.

The STAT headline speaks of “some experts” rather than all, and some were indeed sounding the alarm. And when they did, they were given space in professional media to do so. Scott Gottlieb, the commissioner of the FDA from 2017 to 2019 wrote in CNBC on January 26 of our need to be prepared. That piece shows great foresight about the need to get testing scaled up through the development of quick tests, also suggesting that point of care administration of the tests be authorized, rather than relying on specialized labs. Gottlieb plainly states that “global spread appears inevitable. So too are the emergence of outbreaks in the U.S., even if a widespread American epidemic can still be averted.”

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, wrote a New York Times opinion piece on January 20th, “Is it a Pandemic Yet?” In it, he made it clear that the virus was not going to be contained (indeed, it was “never going to be contained”). Osterholm also says—on January 20th!—that “Unlike Ebola, SARS and MERS, individuals can transmit this coronavirus before the onset of symptoms or even if they don’t become ill.”

Clearly, expert messaging was mixed, but erring towards avoiding the appearance of alarmism. In as much as America’s too-slow response to COVID-19 was a reflection of the state of the expert community, it seems unrealistic to expect journalists as a class to have fared better.

Media vices

If there is a single general problem that cuts across media of all types—including social media and blogs—it is the urge to give a clear answer in an authoritative tone. This tendency manifests most intensely in headlines and when official social media accounts link to the articles. Here is a sampling of ones that did not age well:

Don’t Worry About The Coronavirus. Worry About The Flu.

Buzzfeed, January 28

Is this going to be a deadly pandemic? No.

Vox, January 31

Get a grippe, America. The flu is a much bigger threat than coronavirus, for now.

The Washington Post, February 1

Who Says It’s Not Safe to Travel to China? The coronavirus travel ban is unjust and doesn’t work anyway.

The New York Times, February 5

MD Flu Deaths Climb As Flu More Worrisome Than Coronavirus

Patch, February 23

In many cases the pieces were much better than their headlines or social media taglines. That is a valid excuse for the authors of the pieces, but not for the publications. The fact of the matter is that vastly more people will see the headlines and the tweets than will actually read the articles. The information conveyed by the one-liners will travel far and wide while the subtleties will be picked up by only a minority of those who even click the link. It is irresponsible behavior even when there is a business case for it, and that business case ultimately falls apart when your industry gets demolished by the subsequent fallout.

Another questionable tendency across the board is to stick to certain formulas no matter what the subject matter. So this infectious disease plan from the Elizabeth Warren campaign may seem timely, appearing as it did on January 28th and talking about the coronavirus. But in fact it hardly talks about that at all, and just uses it, and previous examples like the 2014 Ebola outbreak, as a vehicle for talking about her typical hobbyhorses—even climate change and the opioid crisis make it in there, somehow. Compare this to Chuck Schumer actually calling for preparedness here and now back on January 26th.

In characteristic fashion, Cass Sunstein used the opportunity to tell us all that we were irrational for worrying, pulling “probability neglect” out of his behavioral economics hat on February 28th. By March 26th, without reference to the previous piece, he was assuring us that a rational cost-benefit analysis confirmed his new belief that strong mitigation measures were justified.

Many focused on the potential for racism against Asians, which of course is a valid concern. But these authors were clearly writing to a formula—how (fill in the blank) will impact marginalized communities—without bothering to examine the relevant details of the case. This time, it had the effect of making it appear that concern about an unfolding pandemic or valid criticism of the Chinese regime was nothing but a knee-jerk racist reaction. Similarly, The Huffington Post was more interested in projecting a conspiracy theory onto Tom Cotton, who was sounding the alarm in January, than investigating the risk of the virus. Cotton had speculated that the virus may have spread as a result of an accident in a Chinese lab, a story now considered credible enough to cover in The Washington Post (if not to accept as demonstrated truth), but The Huffington Post interpreted it as referring to the conspiracy theory that COVID-19 was developed as a Chinese bio weapon.

All of the above is unwarranted when the stakes are high, and all of them are structural features of our current media system. This is not a council of despair; we ought to continue to think creatively about what is possible and encourage entrepreneurship. But realistically we should expect these vices to remain characteristic of the media landscape for the foreseeable future.

Fox News

Fox News is the juggernaut in the conservative media space. To a considerable degree, it is thaspace. While there was a great deal of fanfare around the rise of Breitbart, its star has fallen precipitously. Meanwhile, traffic to Foxnews.com “has doubled since 2015 and is now at more than 100 million unique visitors per month” generating “ten times the audience of any other conservative news website offering original content.” Fox is also at the top of all cable news channels though still smaller than the smallest broadcast network evening news audience. In short, understanding their coverage of COVID-19 goes a long way towards understanding most of what conservative audiences have seen over the past few months.

The Internet coverage is not unmixed; in February Fox was largely following the same narrative as most mainstream outlets. A February 3rd piece opens with “Experts believe the highly transmissible coronavirus will become a pandemic as infected numbers continue to increase in China and countries around the world” and continues:

The coronavirus is reportedly spreading at a similar pace to influenza compared to the slow-moving SARS and MERS, according to the New York Times.

“It’s very, very transmissible, and it almost certainly is going to be a pandemic,” Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, told the paper.

But two days later they published two pieces by doctors on the Fox News payroll strongly downplaying the danger. From one:

“Americans have no reason to panic over the coronavirus, Fox News medical correspondent Dr. Marc Siegel said Saturday.

“People are walking down the street with masks about a virus that literally only has infected 12 people” in the United States, he said.”

And another written directly by a Dr. Robert Siegel:

And a fourth – and worst-case – possibility is that the coronavirus will not be contained and will run rampant across the Earth, as was the case with the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. While fear mongers may focus on this scenario, it is very unlikely to come to pass based on what we have seen to date.

Though he goes on to emphasize the importance of fighting the virus with:

surveillance and containment; treating infected individuals; greatly increasing the availability of diagnostic tests in every populated region of the world, including traditionally underserved regions; and facilitating international cooperation and communication regarding the virus.

A February 26 piece quotes a former FDA official cautioning against “overreaction.” It does not mention that he is affiliated with the Hoover Institution and Competitive Enterprise Institute. This is a pattern: doctors write pieces or are quoted who may or may not be experts on infectious diseases specifically, but are mostly affiliated with Fox or someone in the conservative ecosystem. I did not find a similar tendency in February COVID-19 coverage on CNN and MSNBC. The quality of information in which Fox relied on “internal” experts or any sort of personality-driven piece like this was markedly worse from pieces like the February 3rd one, which were not very different from reporting done at competing, more liberal media outlets. One way in which they were different is that Fox appeared more likely to rely on “experts” of the caliber of “Dr. Linda Anegawa, an internist with virtual health platform, PlushCare” rather than the professors running infectious disease centers at universities whose quotes frequently appear in pieces by Fox’s liberal competitors.

The most egregious coverage is the constant stream of sycophantic Trump coverage bordering on a cult of personality. See this glowing praise on March 12th for Trump’s complete fixation on the stock market rather than fighting the disease to get the flavor of this style of coverage. As Trump’s take on the pandemic could be described as fact-free and erratic at best, and fictional yet incomprehensible the rest of the time, Fox has been a willing and enthusiastic partner in spreading Trump’s terrible messages to the public.

Coverage of Fox’s bad behavior has focused entirely on the cable news hosts. These have been undeniably terrible. On March 9th, Trish Reagan called the pandemic an “impeachment hoax”—though Fox “parted ways” with her afterwards, ostensibly because of it. Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham have repeatedly argued that the whole thing is a conspiracy by the Democratic Party to hurt Trump. It’s quite bad, and the 4-5 million viewers of these programs are no doubt a disproportionate source of the pathologies we’ve seen from the right around COVID-19 response, including the recent wave of protests against state shelter-in-place orders. One notable exception here is Tucker Carlson, who on March 10th sounded the alarm and took the unusual step of reaching out to the President personally to try and persuade him to take the crisis seriously. Carlson currently draws the second largest audience on Fox after the President’s daily briefing; so his getting this right is by no means a trivial exception. But it is, undeniably, the exception.

Conservative mid-tier

Beyond Fox, where the audiences are much smaller, we find coverage that is both much worse, and much better. In the former category, we find Ann Coulter arguing that COVID-19 is less dangerous than the flu, while citing a graph which shows the opposite. This narrative was popular across the board in January and February, but not when Coulter invoked it on March 24th. Heather Mac Donald wrote a widely shared article making the same argument on March 13th.

A March 23rd piece at The Federalist boldly asserted “it seems harsh to ask whether the nation might be better off letting a few hundred thousand people die. Probably for that reason, few have been willing to do so publicly thus far. Yet honestly facing reality is not callous.” On April 3rd, it was still screaming “We Cannot Destroy the Country for the Sake of New York City.” Co-founder Sean Davis’ consistent position through March down to the present, expressed frequently on Twitter, is that we are experiencing a media-induced hysteria aimed at destroying the economy in order to take Trump down with it. The Federalist is irredeemable, making Fox hosts look almost sensible by comparison. It has clearly been moved by no principle beyond expressing the opposite of what liberals believe; an absolutely atrocious case of unhinged partisanship.

Worst of all perhaps is The Gateway Pundit, conservative blog-turned-professional and famously granted a White House press pass by the Trump administration. They did not have a great track record going into this pandemic, and have not covered themselves with glory throughout it. They have served as a hotbed of conspiracy theories and misinformation. In terms of audience these two publications are squarely in the third tier of conservative media, still far too large to be called fringe.

Conservative media was by and large worse and later on COVID-19 than the rest of the information sphere. Yet even here the largest publication, foxnews.com, was largely mirroring experts in January and February—albeit less consistently than its competitors and with gaping lapses. As experts became more alarmed, Fox articles reflected this, more or less. Tucker Carlson’s sounding of the alarm on March 10 was quite close to the end of the six week window we outlined above, but it was within it, and the message was unequivocal. All of this, along with the more informal actors in the community who sounded the alarm earlier, adds up to important information being available to conservative audiences, even as a number of media personalities and secondary and tertiary publications turned sharply against the necessary mitigation measures.

Looking ahead

Pandemics have long been among my favorite topics to teach sociology with, not because the subject is cheery, but because they contain so many of the lessons about our modern world.

Zeynep Tufekci in 2014

Sociologist Zeynep Tufekci was paying attention to COVID-19 back in January and sounded the alarm in a February 27th Scientific American article. Looking back in March, she highlighted how hard it is for journalists to think in terms of complex systems. The existence multiple points of failure in such systems means that many things can go wrong at once; the fact of nonlinear effects—for example, when the doubling time of COVID-19 cases shrinks by a day or two—means that a small number of cases can become tens of thousands of cases well before journalists have decided to take a problem seriously. Journalists by trade must cover events unfolding in a complex world; providing them with better conceptual tools is one way that the media might be improved.

Pseudonymous blogger Scott Alexander does not believe that the media failed at prediction, calling its performance “A Failure, But Not of Prediction.”

Prediction is very hard. Nate Silver is maybe the best political predicter alive, and he estimated a 29% chance of Trump winning just before Trump won. (…)Predicting the coronavirus was equally hard, and the best institutions we had missed it. (…)The stock market is a giant coordinated attempt to predict the economy, and it reached an all-time high on February 12, suggesting that analysts expected the economy to do great over the following few months. On February 20th it fell in a way that suggested a mild inconvenience to the economy, but it didn’t really start plummeting until mid-March—the same time the media finally got a clue. (…)I conclude that predicting the scale of coronavirus in mid-February—the time when we could have done something about it—was really hard.

Judging the media or anyone by whether or not they predicted the exact outcome that occurred is, in Alexander’s argument, “the wrong framework.” While Tufekci suggests a complex-systems framework is invaluable for journalists, Alexander thinks a more basic grasp of probabilistic thinking is the place to start. Both of these are valuable criticism of how journalists approach their topics. And both have received a fair amount of attention.

The greatest virtue of our open information sphere is the space it creates for ongoing conversations, rather than the authoritative declarations of article headlines. Tufekci’s retrospective, as someone widely published in big professional media outlets, is framed as community self-criticism, something there has been no shortage of.

These conversations are not only valuable for media self-scrutiny, however. Consider the debate around whether or not masks effectively curb the spread of respiratory diseases. Proponents of masks have been frustrated by the standing guidance from WHO and the CDC that civilians should not use masks. In an earlier era—or in contemporary China—they may have simply had to live with that frustration. But in our open information sphere, they were able to mount a campaign. Tufecki wrote about it in several places, including The New York Times. A group of tech-types put together an extensive collection of studies on the subject.

But the best discussion in our estimation is Alexander’s, on his blog. He does not flinch from the uncertainty and ambiguity of the evidence. His goal is to encourage his readers to think pragmatically on important topics for which no perfect, randomized control trials can be conducted. He presents many studies that cut against the conclusion he is arguing for and explains his rationale for drawing that conclusion nevertheless.

The collective efforts of mask advocates paid off; on April 3rd the CDC reversed its long held position that the public ought not to bother with masks. More to the point, the mask campaign appears to have influenced public attitudes more broadly. The CDC decision both reflected this and compounded it.

Our open information sphere has many vices; above all the adversarial character of much of it is unpleasant and difficult to opt out of entirely. Even the mask debate, which I consider an example of the system at its best, was a source of annoyance to many as overzealous mask advocates relentlessly pushed their message on every front. But in Tufekci and Alexander and Pueyo and many others, we see one possible path forward. Something to encourage, a norm to attempt to spread to professional and amateur media alike. If the categorical, authoritative stance that we see most prominently in headlines is among the worst vices of today’s media, then the conversational stance, which aims at persuasion among equals, is among its greatest virtues. Cultivating it will not guarantee a superior response to the next disaster, but it cannot hurt.

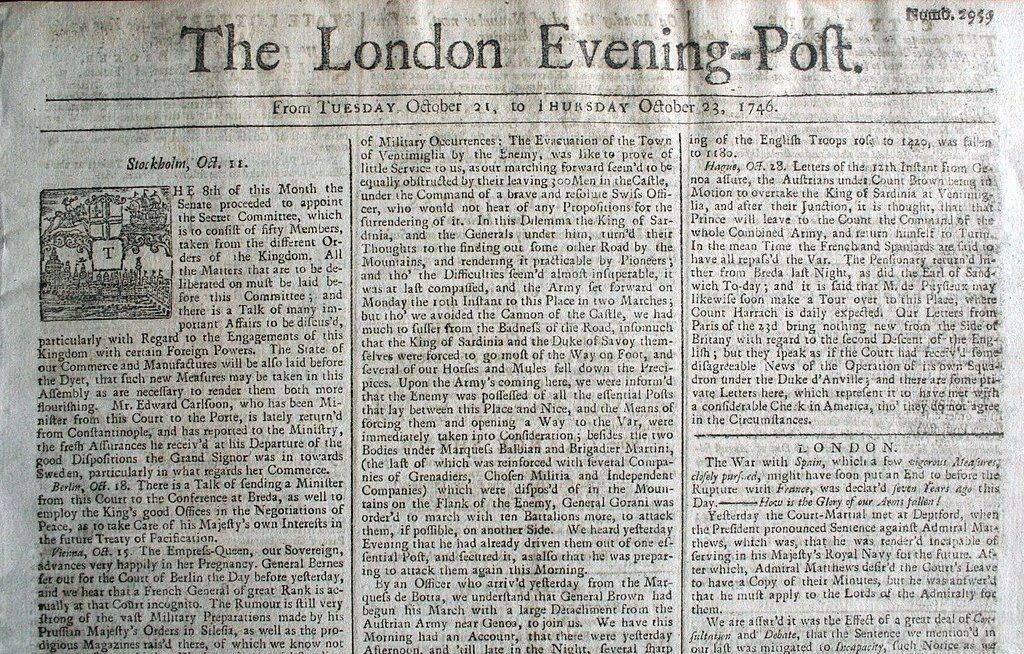

Featured image is Top front page of the London EveningPost for October 21-23, 1746