Ezra Klein, Self-Harm, and Liberal Perfectionism

From the beginning, liberals have felt the need to promote the development and flourishing of human nature in light of the good even if they disagreed about what it might be.

In a recent New York Times op-ed, “Pay Attention to How You Pay Attention,” while drawing on distinctions he derives from the Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel, Ezra Klein made a plea for a “human flourishing” approach to the regulation of social media and AI companies more generally. Klein treats such attention to “human flourishing” as a rejection of liberalism, which Klein associates with state neutrality, and as an endorsement of republicanism (the public philosophy, not the political party), which he quotes Sandel’s Democracy’s Discontent as defining as “a formative politics, a politics that cultivates in citizens the qualities of character that self-government requires.”

As Sandel describes even more in context, the point of such cultivation is to generate civic virtues that allow for public deliberation. Republicanism is the old public philosophy of the New England townhalls, the Church Elders, the State Assemblies, the U.S. Senate and its sibling the faculty senate, and the unlimited liability partnership. Commitment to public republicanism once generated a classical education system geared to the property-owning men who would have the leisure to deliberate in public on the fate of common affairs.

Public republicanism is not wholly anachronistic because it finds its continued use in the Occupy movement, the vegetarian co-op, and the department meeting. There are people who thrive in such environments, but on the whole Adam Smith describes most of our attitudes nicely in The Theory of Moral Sentiments: we would be “much better pleased that the public business were well managed by some other person, than that [we] should have the trouble, and incur the responsibility, of managing it” all the time. This observation is, in fact, the basis for the newer, liberal public philosophy, which accepts the need and not infrequent desirability of the hierarchical division of labor. The liberal philosophy also acknowledges with regret that deliberation is nearly wholly absent and impossible in political life in a mass society.

Despite evincing no interest in civic virtue, public deliberation, or self-government, Klein proposes a revision away from liberal anti-trust policy that he describes as “competition in a market, unlocking entrepreneurial ferocity and genius by lowering the barrier to entry.” Klein thinks the current approach to anti-trust Stateside does not pay sufficient attention to how social media companies facilitate self-harm. And, while Klein is appropriately tentative about any particular policy he would promote, on his “policy agenda” anti-trust has no role in regulating the kind of “control” social media companies have on “our attention.” He is surely right that anti-trust can’t tackle all social problems. More important, Klein asserts that some such attention is incompatible with human flourishing.

What is most notable about Klein’s essay is not so much the reasonable qualms he expresses about certain kinds of technological innovation on the possible development of children or his interest in the philosophical foundations of anti-trust, but his general receptivity toward all kinds of regulations. He approvingly mentions limiting access to online-porn and, more controversially, the banning of access to any social media account to children.

Taken as a whole, the digital and online policies and regulations Klein entertains would involve near-constant monitoring of children and young adults. The data-mining and policing powers involved facilitate not just predictable invasions of privacy, but also foreseeable abuses by authorities against minors and adults. By implementing this system of surveillance, we would educate our young not into the old republican or its rival liberal public philosophy, but into something more dystopian. In the effort to eliminate harm, we risk turning ourselves into coddled, obedient sheep.

In addition, this pro-regulatory stance is surprising coming from the co-author of Abundance, which called for the removal of lots of growth-reducing regulations. Of course, there need not be a fundamental tension here: one can be pro-economic growth and be a paternalist in social policy and distinctly reserved about civil liberties. We have seen that show before; that combination of policy preferences describes the program of ‘fusionism’—the uneasy alliance between libertarians and social conservatives that dominated the American political right in the period before MAGA. It’s surprising Klein would wish to reinvent fusionism.

By contrast, Klein treats what he calls “Modern Liberalism” as “built around the idea that the government should make it possible for people to pursue their happiness as they see fit, so long as they are not harming others.” This naturally evokes Mill’s On Liberty. In fact, if you replace ‘happiness’ with ‘lives,’ then what you have is a central feature of pretty much all liberalism since the early days of Adam Smith, Humboldt, Bentham, and Constant. In honor of this past, let’s call it ‘the core tenet of liberalism.’

Notice, too, that the core tenet of liberalism also focuses on the government’s role in making possible the conditions for people to pursue their lives as they see fit. Often that means getting out of the way of individuals, but on other occasions it means providing resources that allow meaningful or apt choices by individuals. Many policy debates and ideological differences are about the relative weights among these and different views on what works.

In fact, it would not have occurred to any liberal before the 1950s that one could settle these issues by rejecting the desirability of human flourishing; and that without some conception of the good, even the public good, one could decide what policy is ‘best’ (and how to rank its kinds). Between say 1776 and roughly 1950 all liberals were, in the philosophical parlance of our age, ‘perfectionists’ of some sort, that is, they felt the need to promote the development and flourishing of human nature in light of the good even if they disagreed about what it might be. Of course, all of them thought that impartiality in rules and laws were a good thing, but nobody confused that with the “state neutrality” Klein invites us to reject.

To be sure, during the last half century, leading political philosophers argued, especially in light of value pluralism, that the state should be neutral among rival understandings of the good. Many of these leading philosophers also avoid talking about human flourishing. Presumably this idea is the basis for Klein’s criticism of “Modern Liberalism.”

I am myself not an adherent to state neutrality in this sense. But that’s beside the point. Because it would not occur to any adherents of Modern Liberalism that the state cannot prevent certain kinds of self-harms. With the exception of libertarians, Modern Liberalism is wholly at peace with requiring (say) even mature adults to wear seatbelts in a car and mandating motor-cycle helmets to bikers.

It is simply not true as Klein claims that “absent some view of what human flourishing is, we will have no way to judge whether [a digital life] is being helped or harmed.” For even without any commitment to human flourishing, some forms of paternalism are sensible if self-harms also generate considerable social costs. That’s often an empirical question. Of course, the investigation of these facts presuppose some standard or commitment to what’s good or a benefit and what’s bad or a cost. But this standard need not involve flourishing at all. For example, if we are avoiding traffic fatalities we are not taking a stance on the relative merits of Thomism and hedonism.

More subtly, variations of state neutrality in the sense that Klein discusses exist without relying on the arguments and commitments of Modern Liberalism. For, some kinds of state neutrality are baked into many other legal and constitutional principles (the establishment clause, the free exercise clause, impartial law, non-discrimination etc.) that are wholly compatible with all kinds of liberal perfectionism(s) and the old republican public philosophy. And the reason for that is that one often needs some substantive vision of what the government wishes to achieve with a regulation or law in order to make sense of or adjudicate any law. If I am not thinking of flourishing what do I have in mind?

So, for example, and to return us to the details of anti-trust law, in the US price-discrimination of commodities between different customers has not been allowed since the (1936) Robinson-Patman Act. This act aims to create a level playing field and, thereby, protect small businesses. But there is an exception, under the aptly named “Nonprofit Institutions Act,” (1938) that states that some parts of antitrust law do not apply to the purchases of non-profit institutions. The law here is quite clearly designed to promote the activities of non-profit institutions presumably because lawmakers and the public think that non-commercial activities are quite valuable to the public good.

All liberals (old and new) warmly applaud this exception because we recognize that while we may dislike some non-profits, a thriving non-profit sector is an essential part of the social infrastructure that governments should facilitate so that individuals can pursue their lives. In fact, Liberals love free association of individuals into groups dedicated to the common good as they see fit! And while it’s true that these two acts I just mentioned originate in New Deal liberalism, even the most ardent Modern Liberal can live happily with this combination of neutrality and perfectionism.

In fact, if we reflect on the nature of anti-trust law as it has evolved Stateside, there are a lot of practices that seem anti-competitive at first blush, but that are permitted because they are deemed conducive to the public good in some sense if the empirical evidence warrants the judgment. The famous case that illustrates this point is Chicago Board of Trade v. United States from 1918. The lawyers use the so-called ‘rule of reason’ doctrine to analyze such cases. This is accepted by different, competing liberal approaches to anti-trust.

Klein is not only confused about how harm and flourishing relate to each other and to state neutrality, but as my previous paragraph hints at, Klein is also unhelpful in suggesting that there is only one (modern) liberal approach to anti-trust policy. This is not what we find. Throughout the twentieth century and into the present liberals have disagreed about the purpose and the means of antitrust. To simplify these debates greatly it’s worth distinguishing between different questions: is anti-trust policy strictly an economic issue focused on, say, consumer welfare or technological innovation or economic growth? Or is it a political issue that aids in tackling concentrated power that can have all kinds of harmful social and political effects? And should one make an anti-trust policy through rules-based or case-based approaches?

In addition, different markets and technologies may require different frameworks. For example, many modern technologies either have increasing returns to scale or generate winner-takes all market-places (say due to network effects); such markets often look and appear to behave like monopolies even if the companies did not engage in any practice that is self-evidently anti-competitive.

Klein’s proposed “policy agenda” that informs his approach has two components: “First, children should be more insulated from the ubiquity of digital temptations.” Klein fails to point to a single, well-documented pattern of harms that follows from this ubiquity. If such harms exist, and some undoubtedly do, why encourage censorious and authoritarian solutions first? Why not collaborate with schools and families, religious institutions, and neighborhoods to create the infrastructure and norms so that children can play together? Klein’s vision is fear-ridden (“harms” and “temptations”) without any sense of the possible physical and imaginative adventures inherent in childhood. If the evidence shows that the social costs and harms are really extensive in character then national legislation may be warranted. But that should follow from intensive fact-finding established in the generation of, say, case-law or careful law-making or administrative regulation.

“Second, companies that want to shape so much human attention need to take on more responsibility, and liability, for what might go wrong.” This is unobjectionable from any liberal perspective. We should, indeed, be alarmed that digital/AI corporations can marshal their financial resources and political influence to insulate themselves from ordinary product liability and tort law, or to impose top-down bans on state legislators. But oddly Klein fails to discuss or evaluate the two known political weapons to combat such sinister influence: much stricter campaign finance regulation or, and now we come full circle, the use of antitrust to combat concentrated corporate political power.

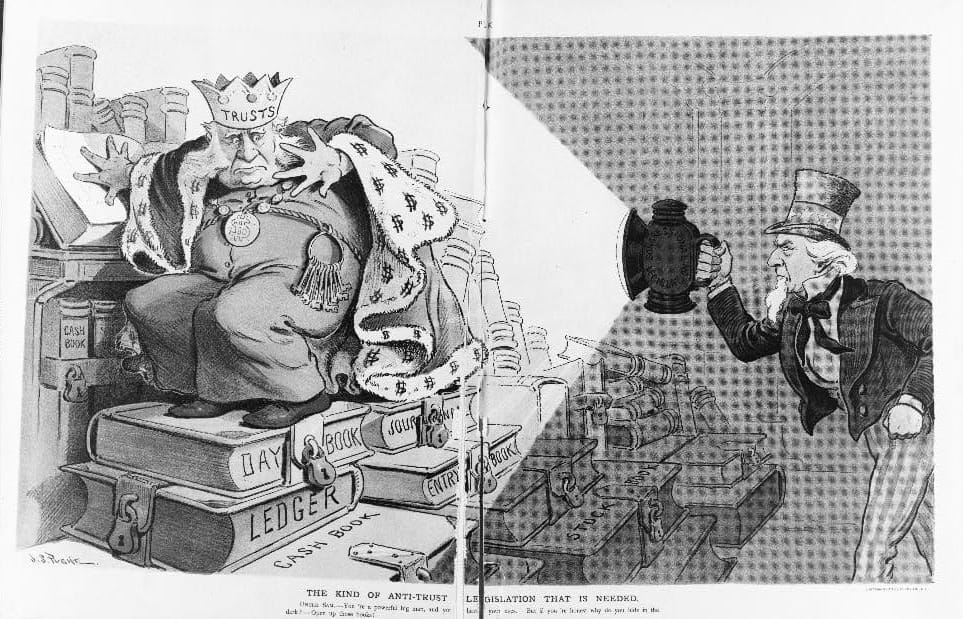

Featured image is The kind of anti-trust legislation that is needed, by J.S. Pughe