From Pill Mills to Prop Bets: Prediction Markets and Mobile Sports Betting Apps Are Fueling America’s Next Addiction Crisis

Against the gamblification of the world.

Monday, the Wall Street Journal published a look at how one young man, Liam Kane, won and lost tens of thousands of dollars during the Super Bowl by betting on prediction markets. As the piece notes:

Kane spent most of the Super Bowl with his back to the television screen, watching his software update odds for various bets across markets. As the game went on, his long bet on New England crumbled. Kane did win a $30,000 trade against a bettor on the total number of points scored in the game, though.

Prediction markets are one key component of America’s flourishing online gambling ecosystem. And they rely on the type of wager that many experts see as being at the heart of modern problem gambling: the prop bet. Prop bets (more formally, proposition bets) are bets that can be placed on specific eventuality, from how many touchdowns a quarterback will throw in a game to, yes, whether Jesus Christ will return in this calendar year.

This gamblification of the world is the business model. Prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket proudly boast that users can bet on just about any proposition imaginable. Will the new Emerald Fennell Wuthering Heights movie get a Rotten Tomatoes score over 72? You can bet on that. Will Dana White attend the State of the Union? You can bet on that. Kalshi even runs ads to that effect, which are striking in their reckless promotion of betting on everything.

In the arena of mobile sports betting, popularized by companies like DraftKings and FanDuel, prop bets are supercharged by parlays, which allow gamblers to string multiple bets together in order to hit low-probability combinations of events for big payouts. In addition, mobile sports betting apps can now run live odds and produce new prop bets in real-time during games. These let users bet on the next play or pitch and its outcome. It’s the sort of lightning-fast calculation that wouldn’t have been possible in the age of analog gambling.

Many critics argue that prop bets, parlays, and live in-game betting are the most problematic features of our current gambling ecosystem. These types of wagers are limitless in configuration, incredibly difficult to make money on, and wildly addictive. They’re the heartbeat of mobile sports betting apps, which are predicated on the same bite-sized dopamine delivery, infinite scrolling, and constant nudging that social media companies utilize.

It’s also worth noting that the explosion of these kinds of bets has fueled a new era of scandal in American sports. Players don’t need to throw whole games for big gambling payouts. They can engage in smaller, harder-to-catch, manipulations like ensuring they only make a certain number of three-point shots in a given quarter or opting to throw their first pitch into the dirt.

Leagues are insisting that they take the integrity of their games seriously and that they don’t want to see them spoiled by gambling’s grim associations with criminality and addiction. But this rings hollow when players are featured in DraftKings and FanDuel ads, and those same companies have sponsorships across American professional sports. It all reads more like a party, celebrating and inviting betting at every turn, and indifferent to the temptations being posed to young players or to the viewer at home in the grips of a downward gambling addiction spiral. A study of the 2025 Stanley Cup found that viewers took in an average of 3.5 gambling ads a minute between logos, filmed advertisements, and other messaging.

Well before the explosion of mobile and online sports betting, we knew the toll gambling addiction could take on individuals and on the people around them. But in the past, placing bets still involved some effort from the gambler. In short, there was friction. You had to go to a bookie, visit a casino, or purchase a lottery ticket at the register. In many places, you could be a day’s journey from somewhere you could legally gamble. This all required effort, a concerted series of choices and actions.

Again, it’s this frictionless element of modern betting that is perhaps the most nefarious aspect of all. And it is something that addiction experts see as a fatal flaw. And gambling companies marry that ease of use to the shiny tricks of social media like Facebook and Instagram.

In observing the contrast between mobile betting and the gambling of the past, researchers Jonathan D. Cohen and Isaac Rose-Berman write:

Beyond easier access, much of the increase in online gambling is due to the fact that gambling companies have engineered their games to be ever more difficult to resist. They feature the same behavioral nudges and dopamine delivery mechanisms as social media platforms. These are not your grandparents’ slot machines.

Every part of a gambling app is designed to be fun, easy to use, and hard to quit. After a cursory age-verification process—basically nonexistent on some unregulated sites—bettors can deposit money as easily as buying anything else online. The apps have their own version of the endless scroll, with a constantly updating menu of things to bet on.

The effects are cataclysmic. Surveys have found that nineteen percent of 18-to-24-year-olds qualify as problem gamblers, and thirty-seven percent of Gen Z gamblers self-report as having an addiction. A 2025 Siena poll found that forty-eight percent of all men aged 18-49 have an active online sports betting account. Cohen, the author of Losing Big: America’s Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling, laid out in one 2025 interview how the scale of problem gambling can quickly escalate:

Problem gambling is the kind of issue that has a lot of societal side-effects. So there’s a study from Australia [sic] that every person who’s addicted to gambling, either through their financial needs or their psychological needs, their addictions will affect five to six other people. So, you can do the math…all the sudden we’re talking about tens of millions of people who’ve been affected one way or another by problem gambling.

Aside from the data, we also have numerous personal stories detailing the struggles of gambling addicts on these apps and the damage caused by their use. In a 2025 article, one bettor told NPR how he lost over $100,000 between 2022 and 2024, succumbing to a gambling addiction he just couldn’t kick and feeling constantly enticed by the notifications and perks from his FanDuel app. The results were devastating:

I thought about suicide on numerous occasions. I didn't feel like I was a valuable member of society anymore. I felt like I wasn't contributing anything and I just wasn't meant to be here anymore

Experts and public officials are waking up to the problem, but it’s not clear how easy it will be to enact change. In late 2025, Massachusetts State Senator John Keenan told the Cape Cod Times that he regrets his vote to legalize sports betting and has now filed a bill designed to regulate the industry, including banning prop bets.

But if regulators and mental health experts are sounding the alarm, executives at prediction markets and betting companies are full speed ahead.

In response to calls to ban prop bets, DraftKings CEO Jason Robbins scorned this as “crazy” and an overreaction to “anomalies” of athlete misconduct. He told Front Office Sports that banning prop bets would only put them “back into the illegal market and create bigger problems long term,” before discussing his desire for DraftKings to get into the prediction-market game directly.

In the last few years, we’ve been treated to some dazzling and deeply tragic exposés of the American opioid crisis that Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family played starring roles in creating. Works like Beth Macy’s Dopesick and Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain have shown how executives, salespeople, and doctors pushed a drug with astronomical risks for addiction and abuse as safe, continuing to deny these facts even as overdoses and criminal activity related to OxyContin skyrocketed. All the while, they advocated less regulation, more OxyContin, and continued to deny any suggestion the drug was harmful so long as it didn’t fall into the hands of problem users and addicts—these individuals, by their own failings, were the real cause of any suffering related to Oxy.

It’s not so hard to imagine a future where we look at the CEOs of sports betting companies like DraftKings and Fanduel and prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket as similarly complicit merchants of destruction. We know what gambling can do to those in the grips of addiction. We know that smart phones and the internet, too, have their own hypnotic qualities. The argument that putting a nearly limitless variety of ways to bet online and in people’s pockets, all accessible with a few clicks, does not pose a risk to the user is as absurd as was the claim that OxyContin would be no more habit-forming than an over-the-counter painkiller.

And, like with so many crises, it’s the vulnerable who will pay the highest price. As Brendan Ruberry noted for The Guardian:

The losses…are most heavily concentrated among young men from low-income counties…[Legalized Sports Gambling] seems to push low-savings households, in particular, into greater precarity than is the case for non-betting low-savings households

I worry we are condemning countless problem gamblers and the people around them to lives marked by addiction, financial insecurity, and even deaths of despair. In twenty years’ time, I suspect we will wonder how we ever allowed this to happen.

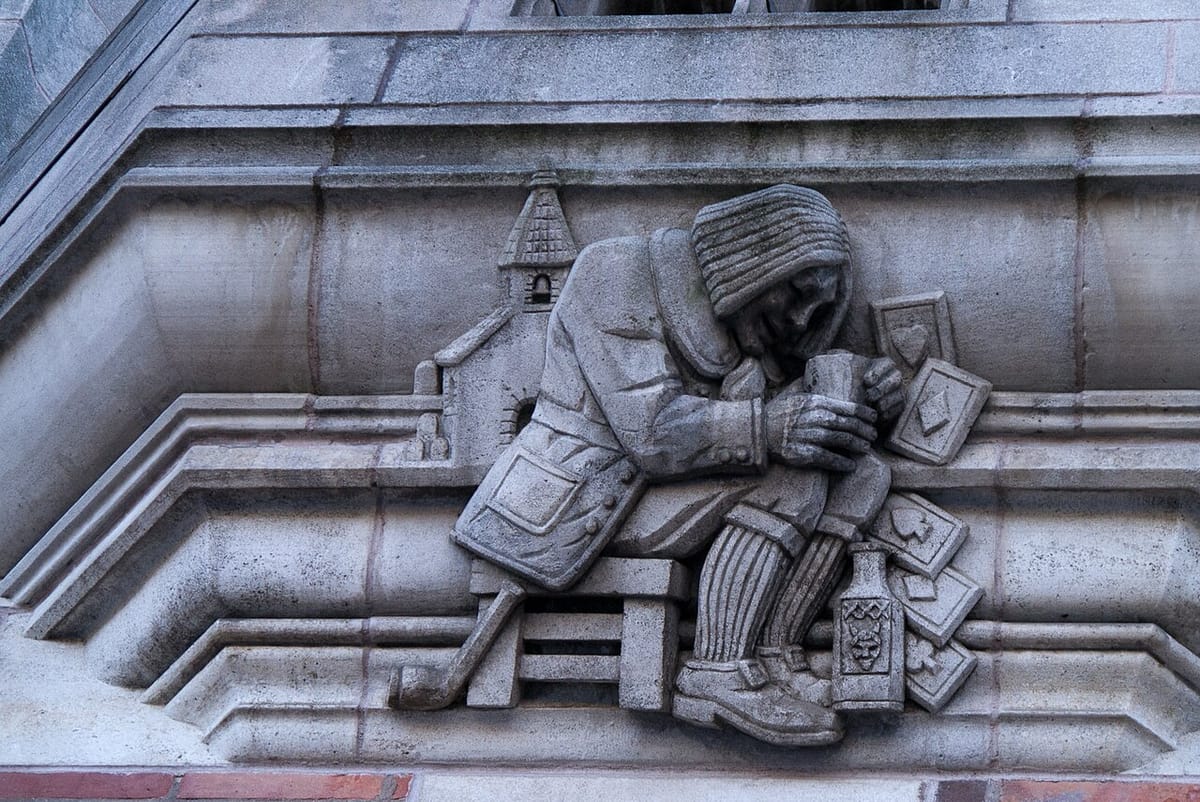

Featured image is Regretful gambler lost in drink, by Rene Paul Chambellan