America's Future is African

The security and prosperity of nations does not depend on complete uniformity of thought, manners, or coloration.

Something unprecedented is happening in the United States of America. Over the course of a few decades (1990-2020) four times more Africans landed on U.S soil than during the entire period of trans-Atlantic slavery. Neeraj Kaushal, the Columbia University economist who came up with this statistic, recently told The Economist that the share of African migrants to the U.S. grew from a mere 1% in 1960 to 11% in 2020.

This extraordinary migration of African peoples is part of what William Frey, a Brookings Institute demographer, calls the 'diversity explosion.' As people immigrate, intermarry, and have children on U.S. soil, they reshape the ethnic composition of America, sometimes at a remarkable rate. The political commentator Eric Kaufmann describes this global phenomenon as a 'whiteshift', a process of cultural integration whereby "white majorities absorb an admixture of different peoples through intermarriage, but remain oriented around existing myths of descent, symbols, and traditions." (Whiteshift, p.2)

Vice President J.D. Vance is the poster child of the whiteshift: married to a woman of Indian descent and committed to all of the nation's celebrated myths and conservative values. Usha Vance’s parents—Radhakrishna and Lakshmi Chilukuri, both science professors at San Diego universities—were part of the first wave of highly-educated immigrants (the so-called ‘First Movers’) who arrived in the U.S. between 1965 and 1979. These highly-skilled immigrants and their children make up just 1% of the U.S. population, but are overrepresented in STEM fields and the technology sector. According to one estimate, Indian-born Americans hold graduate and professional degrees at almost four times the rate of the majority white population, and have about twice the household income of the average white American (Chakravorty, Singh, and Kapur, The Other One Percent, p.43).

Kaushal notes that the current number of Nigerians, Ghanaians, Kenyans, and Ethiopians living in the U.S roughly approximates the size of the Indian diaspora in 1980. This highly-educated slice of the African diaspora is expected to grow by another 10m by 2060, and will join an already racially diverse populace as the new model minority. It is therefore noteworthy that of the 75 nations that have been excluded from entering the country on a visa, 26 of them are in Africa, including all four of these exceptionally well-integrated immigrant nations.

As Tucker Carlson and other prominent right-wing voices have already noted, the number of non-white births in the U.S is currently outpacing that of non-Hispanic white women, adding to the growing number of immigrants from South America. Frey remarks that more than half of all Americans under the age of 18 are now non-white, meaning that Gen Z will be the last white-majority generation. After that you can expect the rest of America to look like the majority-brown state of California: some variation of beige. Frey also calculates that the U.S. will become a white-minority nation as soon as 2045. What is clear to some population experts at least is that this century will mark the end of 'white America' as we know it (The New Minority, p.6).

Of much concern to right-wing commentators is the fact that this 'browning of America' is happening at a time when much of the 'West' is undergoing a fertility crisis. In 2023, France suffered the biggest yearly decline in childbirths since the baby boom ended in the mid-1970s, and the lowest level in any year since World War II. The immigration numbers in France are particularly interesting. They make it quite plain that the U.S. is not the only rich western nation currently experiencing epoch-making levels of African immigration. Insee, France's national statistics agency, reported that for the very first time in the nation's history, Africa has overtaken Europe as the primary continent of origin for people migrating to France. In 2023, for example, 45% of new arrivals came from Africa. It is a standard joke in French comic circles that, if anything, the French national football team looks more like the National Team of Mozambique than a team drawn from the direct descendants of the Gauls.

The African influence on French culture goes well beyond soccer. By 2050, the majority of French speakers (85% of them) will be in Africa, with the Congo and the Ivory Coast slated to become the most populous French-speaking countries in the world. The Ivorian expression 'je visite mon deuxième bureau' (I am visiting my 'second-office') is now a well-understood Parisian code for a secret visit to the mistress. These are the sorts of dramatic changes in social norms and etiquette which the Trump administration views as evidence of the 'civilizational erasure' of European peoples. To understand the appeal of 'the great replacement' theory, and the existing fear of social marginalization among certain figures of the right, it is important not just to pay attention to what is going on in Europe and North America. Just as important is what is happening in Africa.

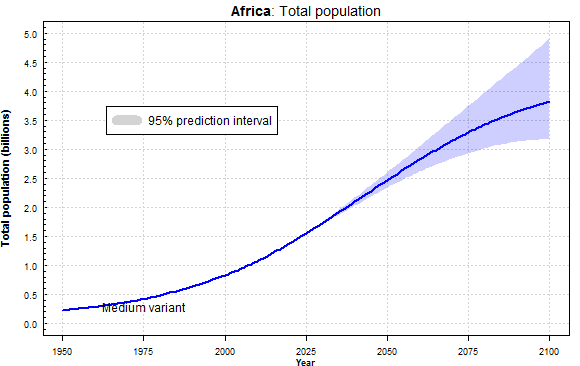

According to the political scientist Robert I. Rotberg, Africa will supply half of all the world's babies for the next twenty-five plus years. More than half of all the projected increase in the global population during this period is expected to come from just 8 countries, 5 of which are in Africa: Congo (D.R.C), Egypt, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Nigeria. By 2100, just 12 countries—all African, except the tiny Pacific island of Vanuatu—are expected to have fertility rates above 2.1 births per woman. The rest of the world will be well below replacement level. By the end of this century, more than 80% of the world's population will be either African or South Asian (Things Come Together, pp. 18-19).

Many of the world's African people will come from Nigeria, Africa's most populous nation, which at 730 million people by the end of the century is expected to outstrip the projected populations of North America (420 million) and Europe (700 million) as separate continental blocks (Things Come Together, p.18). The Economist reports that the 'support-ratio' (i.e. the number of working-age adults for each senior above the age of 65) for all people groups around the world, except those living in Africa, is expected to drop from the current 4:1 ratio to just 2:1 in 2050. According to Michael Clemens, an economist at George Mason University, "nothing like this shockingly rapid disappearance of workers has happened in world history."

As welfare societies strain to replace and take care of more healthy retirees, they will likely seek to tap into Africa's youthful labor pool. The average African today is 19 years of age and part of a 1.5 billion strong continent. The region's population is expected to grow to nearly 3.5 billion by the turn of the century. With such strength in numbers, it is expected that by 2030 half of all new entrants into the global economy will be from Africa. By the end of the century, 1 billion Africans will enter the workforce. Based on a review of these numbers, the Cornell demographers Kathryn Foster and Matthew Hall now believe that "the future of migration will be African in origin." Impressed by these statistics, Clemens goes so far as to describe African migration as "an unstoppable force."

If this is right then one possible way of interpreting the actions of the Trump administration is to understand them as a mighty but ultimately futile attempt to confront this unstoppable force. There is no doubt that Trump's policies have succeeded in retarding the Africanization of American society. By 2024, the immigrant share of the U.S. population was back to levels comparable to that of the 1920s, a time when nativism and anti-immigrant rhetoric was at its peak. These striking facts do not disturb the proponents of mass deportation. As Laura K. Field notes in her new book on the MAGA movement, "The New Right doesn't care." Its adherents, she explains, are opposed to pluralism in principle. They "do not believe in the egalitarian, multiracial, pluralistic democracy that has gained real traction in the United States." (Furious Minds, p. 16) Stephen Miller, for example, has railed against 'the Somalification' of America, while President Trump has deplored the presence of immigrants from "filthy, dirty, disgusting, ridden with crime," places like Somalia.

Despite this global backlash against immigration, there is no indication that the leaders of the OECD will be able to withstand the internal pressures of maintaining large-scale welfare economies. Europe and Asia's fertility is cratering at a frightening rate, leaving most countries with a deepening labor shortage, dilapidated public finances, and a weakening social safety net. The U.S. faces an alarming national debt, and little recourse other than population-driven prosperity to adequately manage it.

And then there is the issue of elderly care. In many towns and cities in America, especially those which have suffered a manufacturing decline, health care services account for the majority of jobs. In Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a town of 80,000, manufacturing jobs have declined considerably, while employment in health and education is booming. As Gabriel Winant explains, the next major shift in labor organization is away from metal industries and towards nursing and human care (The Next Shift, pp. 6-7). As standards of care improve, and Americans live longer lives, these longevous voters will likely clamor for more efficient and timely cradle-to-grave services. When that day arrives expect American policy makers to once more pounce at the opportunity to dip into Africa's bountiful reservoir of youthful talent.

For these and other reasons, says Kaushal, if the United States has a future that future is African. The global numerical superiority of African people may not yet be visible to the average American on the street, but the next 75 years of African migration may yet change this perception. The Economist puts it more bluntly: "African migration is an unstoppable force that will long outlast today’s populists and help define the 21st century. Ignore it at your peril—and at your loss." Most sensitive to this warning are the architects of American immigration policy. In fact, one can read the political history of the past decade as an overwrought conspiracy to undermine one of the core values of liberalism: pluralism.

Liberals do not believe that the security and prosperity of nations must depend on complete uniformity of thought, manners, and coloration. Rather, it is the signature triumph of liberalism that it is able to find unity in diversity by balancing the need for enduring order on one hand and restless dynamism on the other. This modus vivendi, or way of life, is often dismissed by its impatient critics as repulsively romantic and/or childlessly idealistic, but as John Gray reminds us, "a theory of modus vivendi is not the search for an ideal regime." Rather, it "aims to find terms on which different ways of life can live well together." (Two Faces of Liberalism, 6) It is, in this unique way, a deeply practical arrangement, one which future politicians will have to repeatedly consult to learn how to sustain their hyper multicultural societies. Only this time, the leaders of the future won’t have much of a choice about it. Like it or not, the Africans are coming.

Featured image is "Africa: Total Population," United Nations DESA Population Division CC BY 3.0 IGO 2024.