How the Restraint Movement Lost Its Way

The restraint movement's attachment to Trump has compromised its ability to offer a credible alternative to American foreign policy orthodoxy.

When President Donald Trump was re-elected in 2024, many advocates of a more restrained U.S. foreign policy saw it as a “unique opportunity” for their ideas. A solid number of “restrainers” credited Trump with recognizing that establishment policies had faltered and argued that the Republican president-elect “currently speaks more about peace than the Democrats do.”

Andrew Latham of Defense Priorities, declared that Trump’s approach “represents a strategy of restraint aimed at addressing core threats without entangling America in endless global wars.”

Samuel Moyn and Trita Parsi, both fellows at Quincy, perceived an “opportunity” in his “transactional” approach to alliances and disregard for the rules-based order. Analysts at Defense Priorities hoped Trump would “make America’s allies sweat” and “weaponize the uncertainty created by his well-known ambivalence toward allies” to make them adopt a higher burden of defense (which they were already doing after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). Thomas Massie, a Republican who has lately been criticizing Trump’s foreign policy, tweeted in 2024 that “Donald Trump will put Americans first by securing our liberties at home and preventing needless wars abroad.”

Prominent members of the Trump administration, including Vice President J.D. Vance and Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby, supported his 2024 campaign in part to enact a more restrained foreign policy.

These figures are part of the movement for strategic restraint in U.S. foreign policy, which arose in reaction to the overstretch of U.S. power after the Cold War, especially in Iraq and Afghanistan. This is not a formal body with rules and members but a loose coalition of like-minded people as well as institutions and publications such as the Quincy Institute, CATO, Defense Priorities, and Responsible Statecraft.

Restrainers believe U.S. foreign policy is vastly too hegemonic and militarized, and that its excessive interventionism has destabilized multiple regions of the globe and contributed to domestic political radicalization. They recommend acceptance of other powers’ spheres of influence, less reliance on military interventionism and more on diplomacy, and reject the idea that the United States should act as the fulcrum of a rules-based international order.

The Quincy Institute, the leading center of restraint today, identifies as a “trans-partisan” institution that brings together both progressive leftists and traditionalist conservatives who seek to “challenge the decades-long obsession of U.S. foreign policy decision-makers with global military dominance and war.”

However, after half a year in office, it is clear that their hopes for a restrained second Trump administration were misplaced. In June, he abandoned his pursuit of a nuclear deal and launched extensive air strikes against the Iranian nuclear program. He also publicly floated the possibility of assassinating the country’s Supreme Leader and called for the evacuation of Tehran.

Trump has pursued other reckless policies in his second term. He threatened to seize Greenland and Panama by force, backed Israel’s brutal war in Gaza, called for ethnic cleansing there, and continued the air war against the Houthis in Yemen. His ham-handed attempts at diplomacy in Russia and the Middle East have muddied the moral waters without changing the situation. He has requested a 13 percent increase in defense spending while slashing the nation’s capabilities to conduct diplomacy and foreign aid—the very tools that keep America out of wars.

In short, there is little evidence that, as one analyst recently wrote, “under Donald Trump, restraint is winning.” Indeed, one might think that using the words “Trump” and “restraint” in the same sentence is oxymoronic.

These predictive failures are especially stark because we already have four years of evidence that Trump was not a principled restrainer. Despite claims he would be “Donald the Dove,” Trump in his first term escalated the war in Afghanistan, launched reckless attacks like the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, increased military spending, enabled Israeli expansionism, and took other actions that eroded U.S. alliances and militarized our foreign policy.

Not all restrainers made these mistakes. Some pointed out that his first-term foreign policy was marked by erratic disruption and sympathy for authoritarians more than prudence. But a considerable portion of this movement put false hopes in Trump 2.0. Those who misread Trump as pro-restraint include some progressives, but they are clustered in the right-wing of this movement, associated with a tradition of non-interventionism and alliance skepticism associated with figures like Senator Robert Taft and Patrick Buchanan.

These failures reveal concerning problems with the restraint movement, especially within its right-wing faction, which jeopardize its ability to offer a credible, balanced challenge to the orthodoxies of the foreign policy establishment.

First, the restraint movement’s misplaced hopes about Trump stemmed largely from its exaggerated view of the Washington establishment’s hawkishness and incompetence. This created a willingness to give Trump the benefit of the doubt as an alternative, however destructive and irresponsible, to the mainstream.

This caricature led to another problem: too many institutions and publications associated with restraint have welcomed extremists and cranks into the fold merely because they offer heterodox takes on foreign policy. These errors have aligned the restraint movement with illiberal political forces and sapped its overall credibility at a time when critical rethinking of the U.S. global role has never been more necessary.

Caricaturing the establishment

Restrainers have made solid arguments that Washington’s establishment’s close-mindedness and excessive faith in U.S. power led to foreign policy disasters like Iraq. They tend to portray it as a “Blob” that is uniformly committed to U.S. global hegemony, militarism, and interventionism.

Nonetheless, their views of the establishment often sink to the level of caricature, which has made them susceptible not only to faulty analysis of recent U.S. foreign policy but to the false promise of a restrained Trump. Their critiques overstate the unanimity of the establishment, which has largely moved on from ambitious projects of nation-building and regime change. There has been plenty of debate within mainstream institutions about what role the United States should play in the world.

During the 2010s, the Obama administration and liberal thinkers engaged in robust arguments with Republicans and neoconservatives about everything from the rise of Russia to the Iran Nuclear Deal to climate policy. These debates reflected meaningful differences in how the United States should handle threats, relate to institutions and allies, and deal with rising global problems. Senator Marco Rubio and Obama could both have been considered establishment, but that doesn’t obviate their significant differences.

The restrainers also exaggerate the militarism of recent U.S. foreign policy. They are right that the United States over-extended itself in the War on Terror, but their claims that the establishment waged a “Forever War” in the name of global military dominance is untenable as history.

The Bush administration largely abandoned its dreams of democratizing the Middle East by 2007. Obama’s interventions were also more limited in their goals: a brief surge to stabilize Afghanistan, a light footprint approach to global counterterrorism, and a reluctant return to Iraq to combat the Islamic State. His humanitarian intervention in Libya crept unwisely into regime change but did not lead to occupation or a new U.S. war. One can criticize the wisdom and these actions, but they were hardly hallmarks of liberal hegemony or global military dominance.

Moreover, the restrainers’ notion that America is “always at war” obscures the changes in the scale of U.S. interventions in the last 15 years. U.S. troop numbers in Iraq peaked at over 160,000 in 2007 and 100,000 in Afghanistan in 2010, where they were engaged in intensive counterinsurgency campaigns. Obama took these combined numbers to fewer than 14,000 in 2016.

These wars also became less damaging in human terms. 4,432 U.S. soldiers died in Iraq from 2003-2011, while 120 have died in Operation Inherent Resolve since 2014. While Trump and Biden did engage militarily in a number of instances, 65 soldiers died in hostile actions during the Trump administration and 16 died in Biden’s first two years in office. Surely this data belies the notion that the policy establishment is addicted to “endless wars.”

The Failure to Gatekeep

These flawed readings of the policy establishment and recent history made many restrainers susceptible to Trump’s dubious promises. They also contributed to an additional problem: its failure to gatekeep.

Gatekeeping is a hallmark of the mainstream foreign policy establishment, which tries to exclude those without knowledge and/or experience from positions of influence. Gatekeeping can create stagnant thinking, but it also helps channel genuine expertise into the inner circles of foreign policy decision-making, which is highly centralized by nature, while keeping out those with bizarre and conspiratorial views.

However, when you view the establishment as irredeemably corrupt, blinkered, and reckless, and when you view U.S. foreign policy since 9/11 as undifferentiated hegemonic militarism rather than a more nuanced story, you risk embracing anyone who claims to be outside of it, no matter how irresponsible and extreme. Having fallen into this trap, restraint organizations like the Quincy Institute have failed to police the boundaries of their own movement. Instead, they have too often embraced the equivalent of a “no enemies to the right” approach in which extremists, bigots, and conspiracy theorists are treated as allies and potential vectors for influence.

In May 2024, for example, the Quincy Institute and The American Conservative magazine hosted a conference that included Republican Senator J.D. Vance, former Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, Helen Andrews of The American Conservative and the Claremont Institute’s David Goldmon. Inviting Vance was defensible if one’s goal was to court influence, although Vance’s illiberal and anti-democratic views should have raised red flags.

Andrews and Ramaswamy are not foreign policy experts. Andrews is better known for launching racist attacks on black writers, thinly veiled defenses of apartheid, and screeds about the United States “fighting to queer the Donbass.” At the joint forum, she ranted that the “democratic will” of the American people “is being thwarted by what Donald Trump would call the deep state.” Ramaswamy, in turn, is an opportunist and conspiracy theorist who has called January 6 an “inside job.” In his comments at the Quincy event, he called for an end to U.S. aid for Ukraine, which perhaps makes sense for someone who believes Volodymyr Zelensky is a “Nazi.”

More recently, numerous prominent restrainers recently praised Tucker Carlson for his attacks on neoconservatives who want war with Iran. Parsi wrote “At a crucial moment, Tucker wisely advises Trump to drop this deal-killing demand. Huge!” They have also lauded "Jewish space laser" Marjorie Taylor Greene, "Paid a teenager for sex" Matt Gaetz, "Black Crime" Steve Bannon, and “Fredo” Donald Trump Jr. One analyst, writing for Responsible Statecraft, called this crew a “broadening collection of antiwar voices” holding the line against hawks in the Trump administration, as if Trump himself was some sort of peacenik.

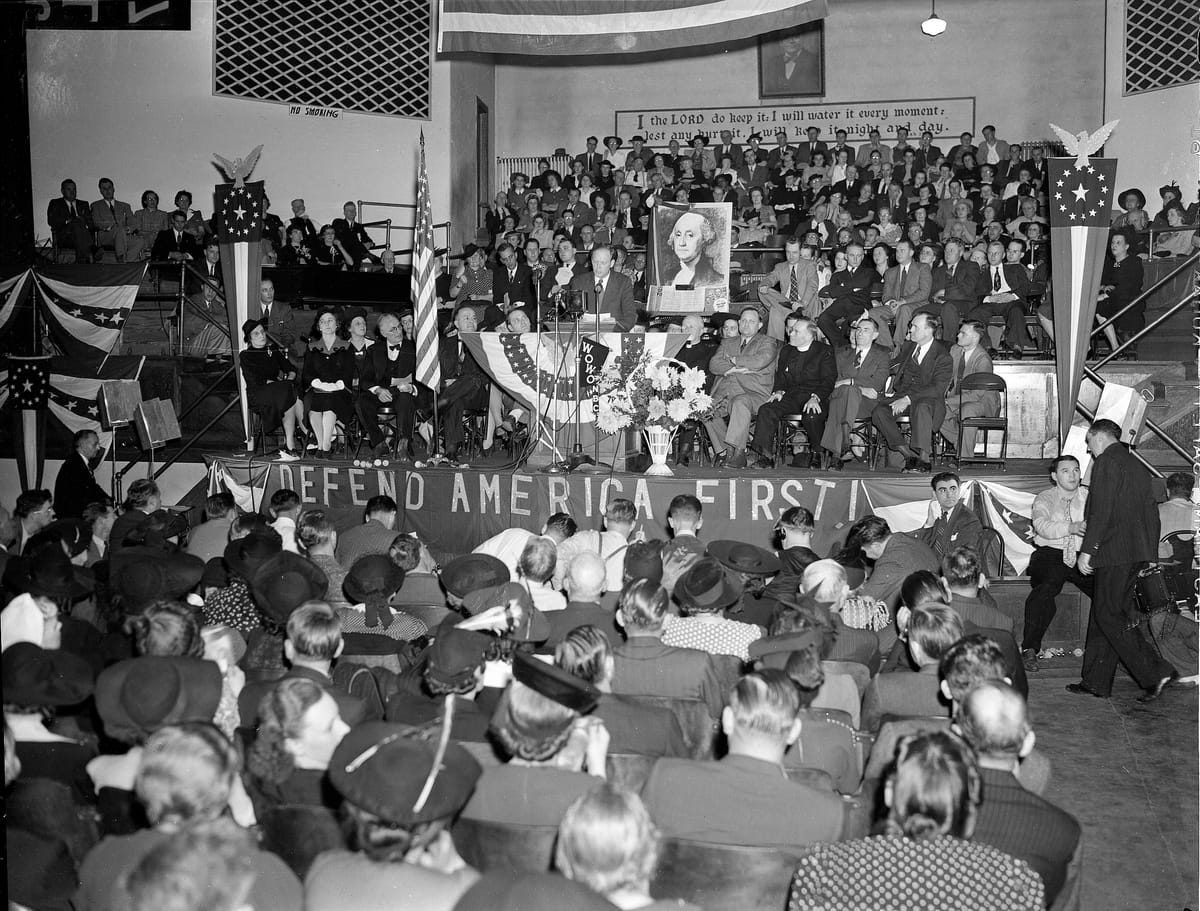

Proper gatekeeping requires institutions to sometimes eschew influence in favor of policing the boundaries of responsible discourse. Tucker Carlson is far from a fringe figure, but as a far-right conspiracy theorist and admirer of dictators he brings immense baggage to the movement. As political scientist Chris Fettweis warned, allying with the nationalist far right puts the restraint movement too close to the nativist and authoritarian anti-interventionists of the pre-World War II era. Today, Claremont and The American Conservative embody the Charles Lindbergh version of restraint, devoted not only to isolationism, but to white nationalism and illiberalism.

This dilemma is especially sharp for progressive restrainers. That the liberal Democrat and restraint advocate Ro Khanna would repost Carlson is especially perplexing. Progressive restrainers may have to reconsider whether this movement is truly “trans-partisan” or if it’s being subsumed into the MAGA world.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The restraint movement can critique the over-extension of U.S. power without legitimizing irresponsible authoritarians who, in the long run, will further undermine American democracy sully their cause, just as Lindbergh sullied anti-interventionism for decades. Some restrainers have struck this balance, but overall the movement has fallen short.

Conclusion

Restrainers must do better if they hope to effectively challenge reigning foreign policy orthodoxy. The restraint movement, as Daniel Bessner has argued, aims not only to change the foreign policy discourse but to “build a cadre” of restraint-oriented experts “able to answer technical questions of foreign policy while simultaneously addressing larger questions.”

It’s a worthy goal, but it requires keeping out racists and conspiracy-mongers while engaging with the complexity of establishment debates. Unless the restrainers want to become an arm of the MAGA movement, they must not act as if foreign affairs can be separated from the assault on democracy and the Constitution that stems from Trump, Carlson, and the far right.

Featured image is "Charles Lindbergh Speaking at America First Rally," 1941