Stop Putting Money in Andy Ngo's Pocket

This past Saturday, Quillette editor Andy Ngo was assaulted by counter-protesters to a right-wing demonstration. This reignited the well-rehearsed debate over the use of violence against right-wing speech by Antifa and related left-wing groups, a debate which this piece will largely avoid. What I will be discussing instead relates to the most direct consequence of this incident: a GoFundMe campaign organized by long-time right-winger Michelle Malkin on Ngo’s behalf, which has at the time of this writing raised over $160,000. This dynamic has come to characterize a great deal of the public conversation and our politics; vigorous opposition, whether violent or not, becomes better marketing for what was opposed than they could have done for themselves. Liberals are going to need to think seriously about how to form an effective opposition which avoids these kinds of outcomes if we’re going to navigate the contemporary media environment successfully.

One This Is Why We Got Trump take that never sat well with me is that the press wasn’t critical enough. The amount of negative press he received, combined with a foundation of conservative distrust for the mainstream press, was crucial to making his candidacy viable. In short, it was the negativity of the press—the very people that conservatives distrusted—which gave Trump both the visibility and credibility he needed with his base. If we want to avoid creating more figures like him in the future, we would do well to think more carefully about who the ideal person to deliver a particular criticism is. Formulating the substance of a criticism is far from enough.

Ours is a time that is not so much post-truth as post-trust. The World War II generation lived through what was probably the peak of institutional trust in recent history. The research university, mass media, the administrative state, and other similarly scaled institutions acted as guarantors of the authority held by their representatives. Today, that trust has all but vanished. As a result, trust has become character and performance driven, and fleeting.

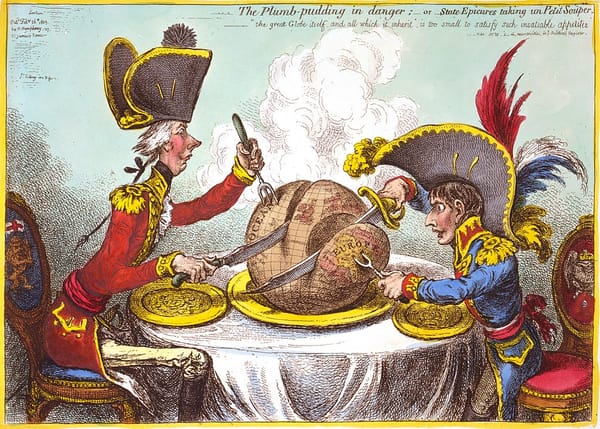

Today, trust is won chiefly by establishing that your audience’s enemies consider you to be an enemy. Jordan Peterson was rocketed to sudden fame when confronted—or “swarmed”—by a group of campus trans activists. Similarly, the enormous outpouring of negative press in 2015 and 2016 was a central element of Donald Trump’s electoral victory. More recently, a relentless conservative campaign to portray Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as a shallow hypocrite succeeded only in elevating her standing to heights unimaginable for a typical freshman congresswoman.

If what you wanted to do was shut out the Donald Trumps, Jordan Petersons, and Andy Ngos of the world, you wouldn’t behave as their opponents did at the crucial moment—showering them with attention. In Trump’s case the free airtime was valued in the billions. But in most of these cases, the most vocal opponents benefit from the rise of the enemies they were ostensibly trying to destroy. The New York Times saw ten times as many new subscribers in November 2016 as November 2015; the story was similar elsewhere and in other mediums. By casting Trump in the role of the enemy against which The New York Times would valiantly do battle, they contributed not only to his success, but to their own. The trust-starved, polarized environment we live in has created a system of mutual benefit among the most vocal representatives of each side.

This freewheeling and character-driven environment is alien to those who grew up in the world of institutionalized trust, but it would have been very familiar to Aristotle. The Athens of his day was similarly mistrusting and antagonistic, rallying behind a speaker one day only to exile them the next. That is why he could clearly see the importance of establishing your trustworthiness as a speaker when making your case. Ethos, the character of the speaker, was central to the art of rhetoric as he and his contemporaries understood it. Ethos is not character in some timeless, absolute sense, but rather the opposite—the character as perceived by a specific audience in a specific context. As institutional trust continues to dissolve, we would do well to rehabilitate these insights from antiquity.

True opposition in the post-trust age

If your goal is simply self-advancement, then the formula described above is all you need. Keep an eye out for an opportunity to attack an established villain, or for someone to turn into one, and attack them as loudly and relentlessly as you can. Cast yourself as defender of a particular audience’s values against the incursion of a common enemy. And repeat. With a little luck and the right timing, you could make tens of thousands a month on Patreon, or launch a media business of your own; prominence creates opportunity.

If, however, you are worried about the way antagonism acts as marketing for what is opposed—if you wish to avoid creating another Trump—the path ahead is much less clear. Other vices aside, it’s hard to call Antifa protesters fame-seeking, given that they go out of their way to conceal their identity. Violent fringe groups aside, I don’t think it’s naive to say that many people genuinely do want to form an opposition against some groups and movements. I have written this piece in the hope that such people would read it.

Going after an opponent means, first and foremost, going after them in front their audience. Not only does this mean that the message should be tailored to that audience’s interests and values, but that the one delivering the message ought to be someone they will take seriously enough to listen—if even for a moment. A tall order in a dismissive era.

The question you should ask is who the right kind of person would be to make a particular criticism for a particular audience, at that particular time. Then ask yourself: can you be that person, to that audience? Sometimes, you can be—if you have enough credibility with the audience already, or there is something about you or your situation that gives you a fighting chance of being trusted by them. A priest criticizing the practices of the Catholic church is more likely to be credible among Catholics than an atheist doing the same, to give just one example.

But no one can be everything to all audiences. There are going to be far more cases where you cannot be the right person to effectively undermine an opponent with the people who find them credible, than cases where you can be. The deck is stacked against you. Even people who might seem relatively well positioned within the opponent’s camp can blow it—see the failure of the NeverTrump conservatives and the tepid response of the Democratic establishment to the rise of Ocasio-Cortez. The mutually beneficial relationship described above makes internal dissent of that kind all the more difficult—the harder liberals went after Trump, the more NeverTrumpers seemed to be complicit with them in the eyes of conservatives.

In such a situation, limited and strategic action is crucial. There is no need to participate in making every Trump typo on Twitter go viral. Save your energy for when you have something his audience might actually care about. Ideally, find someone who they would be more willing to listen to than you and do what you can to encourage them to speak up and help them to be heard.

Martin Luther King, Jr. is an excellent role model in this, as in so many things. In Thomas Jackson’s words, “[King] preached racial unity, integration, and economic justice, varying his language and emphases according to his audiences.” When whites weren’t receptive to his message, “he preached the social gospel,” drawing listeners in with the universal message of Christianity. With labor or socialist audiences, King rhetoric became decisively anti-capitalist, emphasizing the misery that comes with poverty whether you are black or white. With still other audiences, he softened his attacks on the economic system. “King projected reformist and moderate messages to middle-class white and black audiences, but when he spoke to local groups or took inspiration from newly independent nations, he could be quite radical.”

In an interview Jackson adds:

You can see King speaking differently to different audiences. He’s labeled a moderate militant by Auggie Meier in 1965, not because he was both at the same time, but because he spoke to different audiences based on his judgment of their values, what they were ready to hear, but it was safe for him to say. It’s no surprise that in the Dream speech, he would appeal to the Christian and the American nationalist ideals and share this optimistic hope that one day his children would be judged on their character and not their color. But nor is it surprising that a month later with 20,000 trade unionists in Madison Square Garden that he would include a much more radical line from the standard Dream speech. I have a dream that my children would grow up in a nation where property and privilege are widely distributed, a nation which does not take “necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.”

Emphasis added by me.

King’s charisma is still famous today, but the mythical King that American children are taught of in school was charismatic because he possessed an unwavering purity. In a culture that treats strategic, political behavior as morally suspect by default, King’s shrewdness is whitewashed just as thoroughly as his radicalism is. We cannot fully appreciate what King and his allies accomplished without appreciating the delicate rhetorical tightrope they had to constantly walk. To the moderate, reformer, and radical alike, he managed to cast himself as their man—or at least, as the most useful ally available to them. The difficulty of pulling this off and sustaining it over a period of years cannot be overstated.

What it comes down to is picking your battles, and sometimes that means choosing to bite your tongue for now, rather than say something counterproductive to your aims. If you already have a big audience and are an established opponent, speaking up will likely help the very person you want to hinder. If you are simply a private individual, then defining your public character now may tie your hands in the future, when you might have something to say that would’ve been consequential if the relevant audience had no reason to write you off.

To undercut the next potential Trump we will need to be strategic, paying close attention to who the relevant audience is, what they might care about, and what sort of person has a shot at being listened to.

Featured image is Ouroboros, by Michael Maier