If Kirillov Had Drunk Coffee Instead of Tea

I first encountered Fyodor Dostoevsky through Alexei Nilych Kirillov, one of his characters in Demons—not in the novel itself, but in Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, much of which grapples with the philosophical reasoning behind Kirillov’s decision to shoot himself. Camus counters that life’s absurdity is no reason to kill yourself—it might, he says, even be a good reason to stay alive. This claim sounded convincing on its own, but when I sat down a few years later to read Demons, I had some doubts, one of which was a quandary about why Dostoevsky had portrayed Kirillov as drinking so much damn tea.

Kirillov’s tea is as symbolic as his suicide. When his old friend Shatov comes to him begging for some tea because his estranged wife has returned from abroad, he has a pot of boiling tea ready. When Stavrogin, one of the central characters in the novel, sees him for the first time in years, he offers him piping hot tea. When Pyotr Verkhovensky, the main villain, visits and sees that Kirillov’s tea is cold, he worries that Kirillov won’t fulfill his intention to shoot himself—an action on which Pyotr has hinged his entire conspiracy, in which Kirillov takes responsibility for Shatov’s murder before ending his life. Tea is at the center of Kirillov’s entire presence in the novel. He stays up all night, rehashing his theory of free will—the ultimate expression of which is suicide—and ingesting nothing but tea.

I spent years analyzing Dostoevsky’s Demons and even published a book, Narrative Faith, on the topic. And I mostly forgot my confusions about Kirillov’s tea—until the day of the Capitol riots, when I began to be haunted by the image of an excitable Kirillov, sitting at home drinking tea, while his misguided ideas about free will were whipped up into a suicidal frenzy by the manipulative hand of Pyotr Verkhovensky. It was Pyotr’s symbolic finger, I realized, that lay on the trigger of thousands of revolvers at the head of the institution of democracy—revolvers in the hands of an army of misdirected Kirillovs who believed their violence was the ultimate expression of democratic freedom. Kirillov had truly believed that ending his life would be an affirmation of his right to choose life—a flawed idea buttressed by the spirit of revolution that had swept him up—just like the January 6 rioters had believed that defiling the symbol of American democracy would engender a democratic revival. They believed a lie because, when they were not in Washington attending a rally, they sat at home, listening to pundits telling them about everything that was wrong with society, and drinking the Kool Aid—the American equivalent of Kirillov’s tea.

Dostoevsky’s Demons is considered a prophetic novel, foreseeing the Russian Revolution and the violent methods of the Bolsheviks, who turned the Soviet Union into a totalitarian regime. In some ways, Demons also foresaw the fascism of the Nazis, especially the use of the big lie as the center of what ultimately revealed itself as extreme political nihilism—expressed most acutely in the eventual suicides of Hitler and his closest accomplices. It’s probably no coincidence that Jean Merrill du Cane, in a column for The Nambour Chronicle, noted that Hitler “took his tea in the Russian style,” or that a transcript of Operation Foxley, which was meant to assassinate Hitler at the end of 1944, calls Hitler “a tea addict.” It was apparently all part of his long preparation to shoot himself—which he only did after taking about seventy-five million people down with him.

Demons is a chilling reminder of the power of manipulation to bring about real destruction in the world. But the novel’s most maddening element—the one readers tend to overlook—is that Pyotr Verkhovensky gets away at the end. The chief villain isn’t the one who suffers. It’s all the people who believed the big lie. While fires ravage the poor part of town, a governess’s ball turns into a stampede, and factory workers riot for their rights, and as murder and suicide overtake the small group of would-be revolutionaries who unwittingly followed Pyotr’s lead in their desire to make Russia great again, Pyotr packs his bag and retreats. Everyone either dies or goes to jail—but Pyotr hops on an express train to St. Petersburg and is last seen playing cards with an acquaintance he meets on the railway platform. And I can’t help but see Trump’s orange skull superimposed onto that image, flying off on Air Force One to his Mar-a-Lago retreat as the FBI investigates his loyal Kirillovs who shot themselves in the head—or the foot—the moment they stormed the Capitol. Trump, like Pyotr, is left plotting his next intrigue, hobnobbing with his rich goons, while the real people who believed in him die or go to jail.

As I recall Kirillov and his tea, carrying on conversations with Pyotr about the exact wording of his false confession, I find myself suffocated by the idea that the big lie continues—that the Trumpian nightmare we thought we narrowly avoided has only just begun. No one reading Demons in 1871 could have imagined the Bolshevik reality that would take over Russia a few decades later. And few people reading the news item about a failed Beer Hall Putsch in Bavaria in 1923 could have imagined the rise of the Third Reich in just ten years. And it all boils down to a bunch of tea addicts cooking up one big lie after another—which are swallowed whole by people taking their ideas just a little too seriously.

As I reflected on all this, I started to wonder where Dostoevsky’s image of a man who ingests nothing but tea originated, and, sure enough, it came from his own life. In a letter to Polina Suslova, with whom he’d conducted an on-again-off-again romance for years, he wrote of his destitution over gambling debts that left him unable even to pay for his room in Wiesbaden. He writes her: “the hotel declared to me that they would no longer give me any meals. . . So that since yesterday I no longer eat and only drink tea.” Having nothing left but tea was, in reality, the sad state of a bankrupted gambler who had nothing left but to write letters about his destitution. If he’d had Twitter, he’d have probably ranted about Germany strangling the Russian nation by controlling its capital markets. Instead, he just wrote sad letters to his ex-girlfriend, and probably contemplated suicide too. And his suicidal ideation had nothing to do with any big philosophical ideas about free will. It was just the fanciful fantasy of a person who had nothing left but leaves steeped in hot water. It was sad—but it made more sense than Kirillov’s hifalutin philosophizing.

Dostoevsky turned his experience in Wiesbaden into a novel, The Gambler, in which a young man gambles at roulette as a means of survival, but where tea plays no role. As his stenographer, he hired Anna Grigoryevna, and five months later they were married. Less than a year after that, she was pregnant and he was hard at work on a new novel, The Idiot, the composition of which he mentioned in a letter to his niece, Sofya Ivanovnam. “I get up late, light the fire in the fireplace (it’s awfully cold here), and we drink our coffee; then I get down to work. . . . At four o’clock I go out for dinner in a restaurant. . . After that, I go to a cafe, where I drink coffee and read the Moscow Gazette and The Voice down to the last syllable.” The destitute gambler left with nothing but tea is now a married father-to-be who begins his workday with a cup of coffee, and has a second cup in the afternoon. He mentions that, after stoking the fire again later in the evening, he has a cup of tea before settling into a second shift of writing, but it’s clear from the context that it’s the coffee, not the tea, that’s part of his creative mood. From a person who does nothing but drink tea and contemplate suicide, Dostoevsky turns into a creative coffee drinker who writes one of the greatest novels ever written about the hazards of being good.

Kirillov’s tragic end, it seemed, was emblematized by his endless tea-drinking. Stavrogin, who’d drunk down Kirillov’s boiling tea in a single gulp at the outset of the novel, hangs himself in the end. In his suicide note, he writes that, “Magnanimous Kirillov could not endure his idea and—shot himself.” Stavrogin has no idea in which to believe—and this, in itself, is a reason to kill himself. Interestingly, in the chapter that was censored out of the novel—where Stavrogin goes to Bishop Tikhon to confess his greatest sin, the rape of a young girl—he starts the day with a cup of coffee. In Dostoevsky’s universe, it seems, coffee portends the possibility of confession and repentance, whereas tea only reinforces the same destructive impulses that left us with nothing else in the first place. It makes you wonder about the spiritual legacy of the Tea Party—which ushered in the Trump Era—and also about our chances for the Trumpian nightmare to end. Because, tea or coffee aside, we have to recall that Pyotr Verkhovensky gets away in the novel—and that, in our historical reality, Hitler doesn’t die until he kills himself.

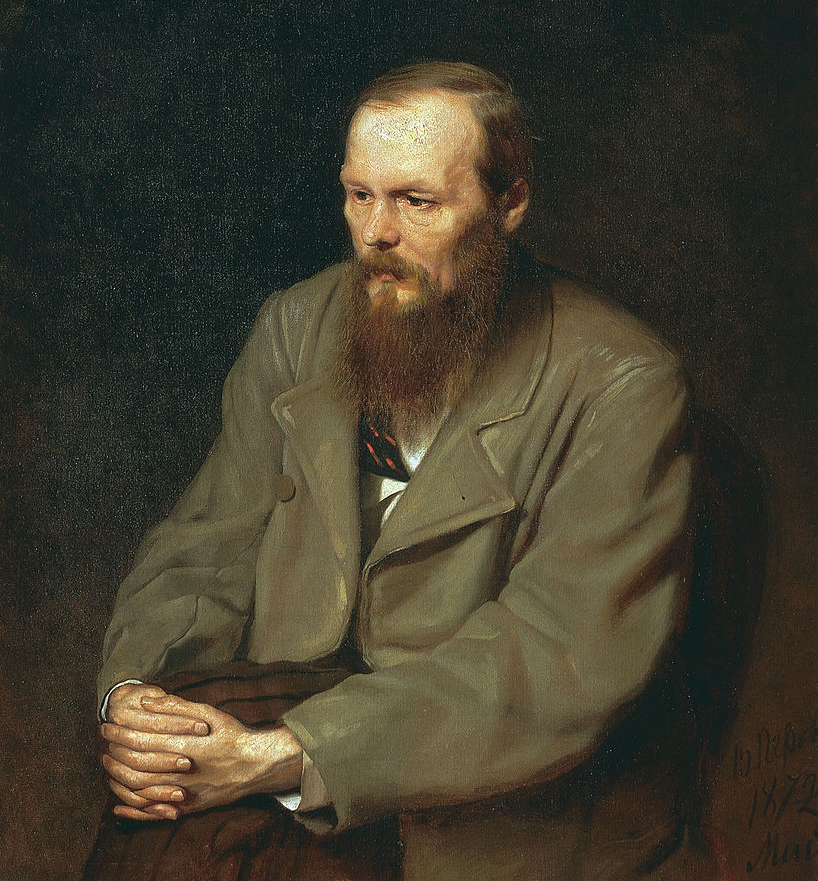

Featured Image is Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky