Is It All Just Envy?

The sides of the inequality debate continue to talk past one another, as Don Boudreaux's recent criticisms demonstrate.

There are a great number of misconceptions when it comes to understanding economic inequality and its social effects. When I published The Greatest of All Plagues: How Economic Inequality Shapes Political Thought from Plato to Marx (reviewed in Liberal Currents), I hoped to clear up some of those by exploring inequality’s deep history, since we are hardly grappling with it as a new problem in the twenty-first century.

One of the most persistent misconceptions about inequality among contemporary economists and public intellectuals is the accusation that people oppose inequality insofar as they envy the lifestyles of the rich and famous, as it were. This was an argument found in Donald Boudreaux’s recent “What the Economics of Envy Can’t Answer.” I responded to this in an LSE blogs essay, in which I carefully explained why the accusation of envy cannot be used to dismiss the very serious objections to inequality found in canonical thinkers, such as Plato, Jesus, and John Stuart Mill.

A day after my essay appeared, Professor Boudreaux responded with an “Open Letter to David Lay Williams” at Café Hayek. I naturally appreciate that not everyone will view inequality problematically and I think we can all benefit from actually engaging the arguments either for or against the phenomenon.

I address Boudreaux’s Open Letter here because it reveals just how much of the inequality debate still involves people talking past one another, but maybe even more fundamentally, how much we can gain from reading the original sources on inequality more carefully. Thinkers like Adam Smith and Karl Marx are not mere slogans. They are serious thinkers, whose works demand careful attention now as much as in their own days.

I take Boudreaux at his word when he allows that “envy isn’t the only, or even the chief, motivating emotion that fuels intellectual and popular hostility to large differences of incomes.” That’s a good admission. Yet Boudreaux certainly mentions envy as a major factor in why he thinks many oppose inequality—the word “envy” is literally in the title of his essay that spurred this exchange in the first place (“What the Economics of Envy Can’t Answer”). So perhaps I can be forgiven for assuming that envy was a serious part of his criticism of egalitarians. It also plays a significant role in the thought of all those others I mentioned earlier—Deirdre McCloskey, Steven Pinker, and Thomas Sowell. I have not fabricated a line of thought in these thinkers; it is, as I hope I demonstrated both in my article, but even more so in my book, a common trope in criticisms of egalitarianism.

Boudreaux proceeds to sketch other more substantive arguments against egalitarians in his letter. Primary among these is the argument that the philosophers I mentioned in my article largely preceded “non-zero-sum” economic thinking. This, on his analysis, renders their thoughts on inequality somehow moot. Per Boudreaux:

Most of the past thinkers who you mention lived before the modern market era. Pre-industrial economies were far closer to zero-sum institutions than is today’s global market economy. Back then, large differences in income were much more likely to result from oppression and special privileges than is the case today. Jesus, St. Augustine, and even Plato spoke and wrote about economies that differed in fundamental ways from the kind of economy about which Profs. McCloskey, Pinker, and Sowell write.

There is no question that their economies differed in important ways from those we find in the developed world today. But I think it would be a terrible mistake to conclude that this renders them somehow irrelevant. Among the concerns raised by thinkers in my book is the corrupting moral effects of concentrated wealth on inequality’s beneficiaries. This has nothing to do with zero-sum economics. This is, rather, a question of character. Plato describes how great wealth, in fact, makes it virtually impossible to become a good person.

Just one example to bear in mind: the friends of Jeffrey Epstein were hardly middle school teachers or “Joe the Plumber.” They were among the most rich and powerful people in the world. Anand Giridharadas has well-articulated the concerns that similarly bothered Plato in his “When No One Is Watching: Inside the Epstein Emails.” One has to be very rich, indeed, to think that cavorting with a convicted and notorious sex-trafficker is somehow permissible. Adam Smith expresses a similar concern in his Wealth of Nations. The fabulously rich often assume the same rules that apply to others simply do not apply to them.

Plato goes on to argue that such corrupted souls go about wreaking havoc for the rest of us. Pleonectic souls (those wanting without the possibility of sating their desires) are, for him and for most everyone in my book, a menace to society. And the richest among us are the most prone to this menacing vice.

Thomas Hobbes was concerned that the very wealthy develop a sense of “impunity”—that they seek to stand above both the moral and legal laws that govern society. This makes them, in his eyes, a threat to sovereign authority and political stability. He would know, as he witnessed the ascendance of the English merchant class and their collective decision to provoke a revolution rather than submit to the ship-money taxes. In our own time, American billionaires have enjoyed enough presidential pardons that Business Insider was compelled to publish an article entitled, “All of the billionaires and businesspeople that Donald Trump has pardoned.”

But beyond characterological questions are simple questions about oligarchy. In an age where the sitting president of the United States was inaugurated on a podium surrounded by the richest people in the world, it is not unreasonable to ask just how much undue influence these people hold over our fates. Rousseau tried to warn us about all of this long ago: “Wherever wealth dominates, power and [legitimate] authority are ordinarily separate; for the means of acquiring wealth and the means of attaining authority are not the same, and thus are rarely employed by the same people. Apparent power, in these cases, is in the hands of the magistrates, and real power in those of the rich.” John Stuart Mill likewise worried about what he called “class legislation,” in which the wealthy would commandeer public policy and make the laws do their bidding.

These very legitimate concerns have nothing to do with “rising tides” or zero-sum economics. They are moral and political questions. As a political theorist, I am within my rights to worry about them—as I think all citizens are so entitled.

One can, of course, dismiss these concerns about character and oligarchy. But, I think, only at enormous costs.

That’s my main response to Professor Boudreaux. Questions about zero-sum assumptions, taxes & transfers, etc. truly have no bearing on the best arguments from the past. This is precisely why I think these old thinkers are still worth our time when pondering the potential dangers of excessive inequality.

But I’d like to make a few smaller points. First, Boudreaux has suggested that Marx was “blind to the positive contributions made by entrepreneurial and capitalist initiative.” This is false. Marx was unquestionably aware of those contributions and said so (along with Engels) in the Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground—what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?

Marx was impressed by the creative capacity of the bourgeoisie and was insistent for this reason that capitalism is a necessary stage of history. Socialism and communism are only possible, in his eyes, after capitalism does its work of advancing technology and productivity.

Second, Boudreaux contends that Adam Smith might only be perceived as an opponent to inequality insofar as he opposed “high incomes gotten . . . through protectionism and other government-granted privileges.” I agree that Smith opposed protectionism and related mercantilist practices. But this is scarcely his only objection to inequality. I strongly encourage those curious about these matters to read the relatively new work on Smith that explores his myriad objections to inequality—including my book, but even more fundamentally the work of Samuel Fleischacker, Deborah Boucoyannis, Dennis Rasmussen, Elizabeth Anderson, Branko Milanovic, Eric Schliesser, Kristen Collins, and others. Smith was deeply concerned not simply with how money is earned. He was concerned about that money’s effect on the character of the rich, on social relations, and the tendency of the rich to dominate the political agenda. To suggest Smith only cared about how the rich earn their fortunes is to radically oversimply a very complex thinker.

Third, there is much reference in Boudreaux’s piece to “income” inequality, but little about “wealth” inequality. As I have argued in my book, I think this is unhelpful and even misleading. This is for at least two reasons: 1) none of the thinkers of the past discussed in my book cared about income. For them that was a non-factor. People’s annual income doesn’t affect their character or political influence nearly as much as their wealth does. Second, as we know today, many of the richest people in the world have strikingly modest salaries. It was reported, for example, that Jeff Bezos, earned $80,000 a year working at Amazon, even as his unrealized stock portfolio gains skyrocketed. To suggest that Bezos is in any meaningful sense poorer than an experienced suburban middle-school teacher is insulting. Measuring income inequality can be useful in some respects—but not on any of the dimensions I address in my book or article.

Finally, Boudreaux has suggested that my “argument rests largely on an appeal to the authority of past prominent thinkers such as Plato, St. Augustine, and Karl Marx.” I want to draw his attention to the final paragraph of my essay:

To be clear, this is not an appeal to authority or to tradition. I’m not saying that simply because Plato and Mill and others condemned inequality that inequality must be wrong. But I am saying that many highly respected thinkers put forward compelling arguments for why inequality can be deeply damaging to individuals and societies alike – arguments that extended far beyond mere envy. What’s more, a great many thinkers seemed to agree on this point. This alone should be a good enough reason to think harder about the matter than many seem inclined to do.

The point is not that the past is always right. That would be absurd. My point is that when we struggle with problems today that resemble those of the past, it’s not unreasonable to consult those who grappled with these problems before us—especially those who have been acknowledged as especially important and insightful on a broad range of subjects. In a world increasingly beset with a host of problems, it strikes me as foolish simply to discount the treasure of long-cherished wisdom.

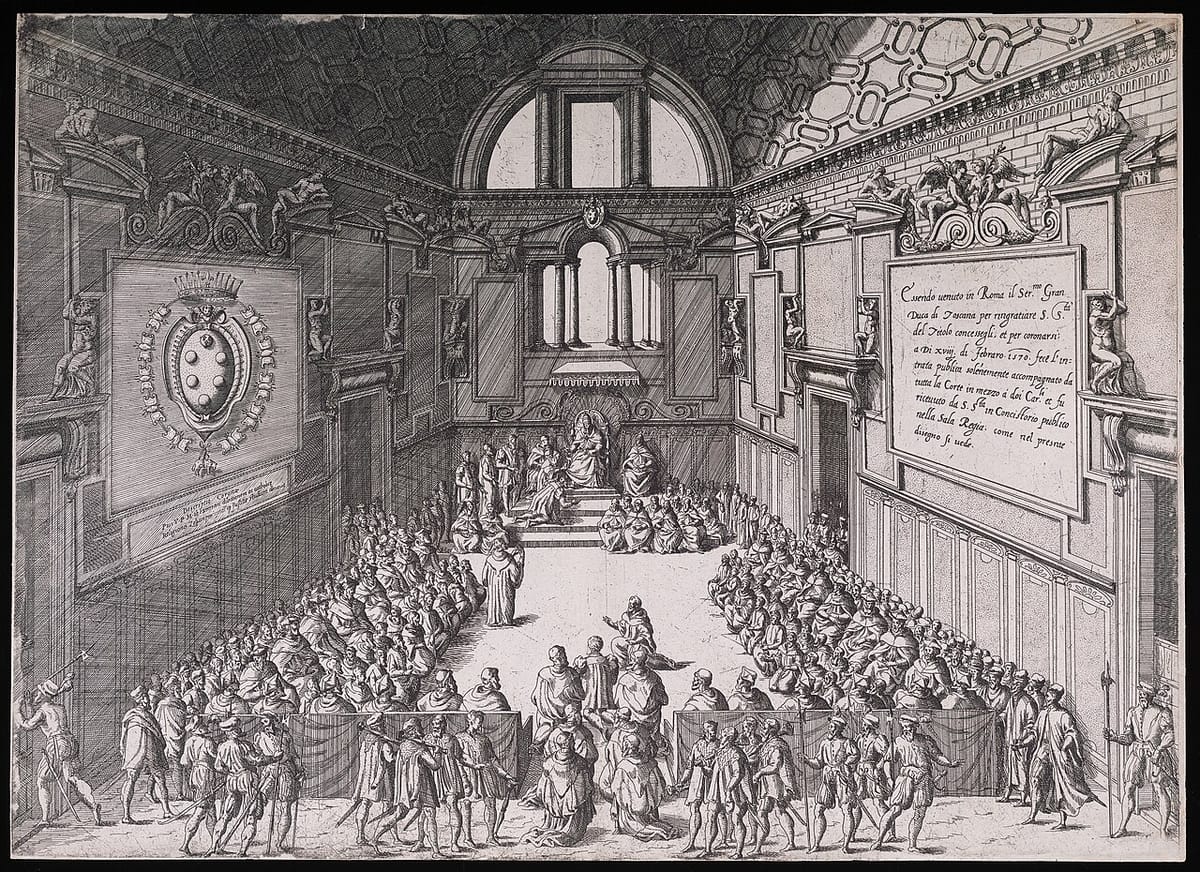

Featured image is View of the coronation of Cosimo I de' Medici as Grand Duke of Tuscany, by C.E. Rappaport