Josh Hawley's "Tyranny of Big Tech" Illustrates the Contradictory Ideologies of the Contemporary Right

Senator Josh Hawley’s Tyranny of Big Tech sets out competing expectations. On the one hand, Hawley is a notoriously partisan figure with a clear political agenda and the aim of eventually becoming President. On the other hand, he’s sometimes praised as a relatively intellectually respectable member of the GOP congressional delegation. The book has a narrow policy focus, oriented towards a potential antitrust action against five particular companies (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter); any potential interest to the book is clouded by Hawley’s insistence on partisan invective and a play at heroism that frequently collapses into a silly, anti-charismatic mess.

Hawley raises the prospect of a serious antitrust action taken by the government against these companies, an action that might break-up these companies and enforce serious regulations. The Federal Trade Commission is already mounting a lawsuit against Facebook that looks to take this action. The problem is that Hawley approaches this problem in a way that is profoundly incompetent in even the most rudimentary technical details. Hawley is so absurdly partisan that one wonders if he is intentionally aping Donald Trump in an Andy Kaufman-esque parody act that the death of satire can no longer accommodate.

The only value of Hawley’s book is as an illustration of the ideological tension in the American right. One cannot be in favor of unfettered capitalism and simultaneously hold that the government should restrict the speech and activities of those corporations when that speech is out of step with the right-wing positioning in the culture wars.

The laissez-faire economic policies that attract wealthy donors and brand the right as “pro-business” are incompatible with the insistence on governing the political positions of those donors and their companies. Being a culture warrior requires insisting on the political positions of corporate leaders; this insistence cannot coexist with a libertarian ideology of deference to private companies. Hawley takes a clear side, rejecting the libertarian position outright, but also engages in a lazy attempt to hand-wave the economic views that have dominated the Republican Party since Reagan.

The Tyranny of Big Tech is bad. It is just a bad book. But it is a bad book about a deeply important, potentially era-defining topic. As such, I want to take this review to outline both why the book is bad and how a politician or legal scholar might approach these issues in a way that is actually constructive and interesting.

Misunderstanding the technology

In early hearings on net neutrality in 2006, Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK) issued his famous analogy, that “… the Internet is not something that you just dump something on. It’s not a big truck. It’s a series of tubes.” The line is now legendary. Some have defended it as an attempt to simplify an issue, but it became a shorthand for a broader political issue: septuagenarian politicians writing policy on technologies (and many other issues) that they simply do not understand.

Sometimes, this line of criticism is in service of technocratic libertarianism, that the technology companies should be empowered to manage and regulate themselves because they are the ones who best understand the technology. That position is nonsense; understanding something does not necessarily make one well positioned to regulate it, especially when their financial success is attached to those regulations. (We will come back to this point below.)

However, the line makes a broader, intuitive, and certainly correct point. If you’re going to write policy governing technology (or the military or transportation infrastructure or public health or baseball), then you need to have at least a rudimentary understanding of how the objects of governance work.

At various points in the book, Hawley’s grasp of the basic mechanics of these technologies is unclear. Sometimes, one might charitably interpret his choices as glossy, in the service of his reader. But that charitable interpretation deteriorates when he gets things outright and importantly wrong. There are many such illustrations of this in the book, but I want to focus on one: Android.

Hawley writes, “Google’s browser, Chrome, holds 68 percent of the global desktop market share and 63 percent of the market for mobile browsing. Its phone, Android, represents 85 percent of smartphone market share worldwide.” (p. 5)

Set aside the contention about the statistics for a moment. “Its phone, Android…” Android is not a phone. It is an operating system. The operating system is the software in the phone which makes the phone run. I am writing this on an ASUS computer, and that computer’s operating system is Microsoft Windows. Confusing the device and the operating system may seem like a small and understandable mistake; if my dad refers to my computer as “your Windows” then I’d have no problem understanding what he was talking about. So, a Google phone would be a Pixel5 (for example), and that phone would run the Android operating system.

It’s the context of Hawley’s comment that illustrates the severity and danger of his confusion.

The two major desktop operating systems, Microsoft Windows and macOS, are owned by private companies (Microsoft and Apple, respectively) and tightly controlled. Contrary to the point that Hawley is trying to make: Android is not owned by Google. Android isn’t owned by anyone. It’s an open source operating system, meaning that any company can use it on their mobile devices (unlike the mobile operating system on the iPhone, which is exclusive to Apple products). The Android open source project is “led” by Google, but that is importantly different from ownership.

So, when Hawley says Google’s “phone, Android, represents 85 percent of smartphone market share worldwide,” he’s not merely making an error by confusing the phone and the operating system; rather, he’s suggesting that Google owns 85% of the mobile market, which just isn’t true. 85% of the market runs an Android operating system, but that includes phones manufactured by Samsung (the Galaxy), OnePlus (the Nord N1), and many other such companies. Hawley is suggesting this is a Google monopoly, and he’s just factually wrong.

Google absolutely profits off of licensing associated with Android products and licensing fees. It is a revenue stream for them, but getting the basic mechanics wrong, including the extent of Google’s market share in mobile phones, illustrates a lack of awareness of even the big picture.

Hawley gets some of the facts right. His claims about the Chrome browser and Google’s various, legally questionable and morally skeevy practices around software contracts are mostly right. The problem is that being right about some things is not enough to restore credibility when making basic mistakes about how the technology works.

Hawley makes lots of mistakes throughout the book. His discussions of content moderation and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act are riddled with basic mistakes that any fact-checker should catch. Hawey suggests, for example, that legal action pertinent to social media platforms’ terms of service is impossible to litigate as a result of Section 230, but this is simply not true and dramatically exaggerates the scope of the liability shield. Section 230 prevents civil suits based on user generated content. Though this has not yet been tested, there is no reason to think that Section 230 would protect social media companies from litigation based on their own failures of implementing moderation policy. One could not sue them for damages based on the content posted by a user, but their internal business practices are fair game.

Many books rest heavily on the credibility of the author. We have to trust that authors have done their research, that they have worked to understand the subject and (while speaking from a point of view) are trying their best to communicate that understanding to us. This credibility is especially important when the author tells us about events and personal experiences that they have privileged access to, like Hawley’s claims about a whistleblower from Facebook who approached him and who was vetted by Hawley’s staff.

Should we trust Hawley’s claims about how his staff vetted the whistleblower? If it’s the same people (himself emphatically included) who developed and vetted the content of his book, then we simply can’t. Even if Hawley is writing in good faith, the basic mistakes indicate that he lacks the technical competence required to avoid major errors of understanding.

Ideological fault lines

One major point of impetus for me to read the book was a curiosity about how Hawley squares the belief in rigorous regulation and antitrust enforcement with the broad anti-regulation, anti-government-intervention attitude that has been the ideological staple of the GOP for decades. What in Hawley’s political ideology might be compelling to Republican voters, yet justifies substantial government intervention and regulation in (at least) the technology sector?

Hawley is writing in a genre that I tend to refer to as the “I’m Running for President” book. It’s a way of testing out messaging for a presidential campaign by drawing on historical and intellectual influences. This genre is insincere by conceit, but the choices in such books are sometimes illuminating. Hawley’s is one such case.

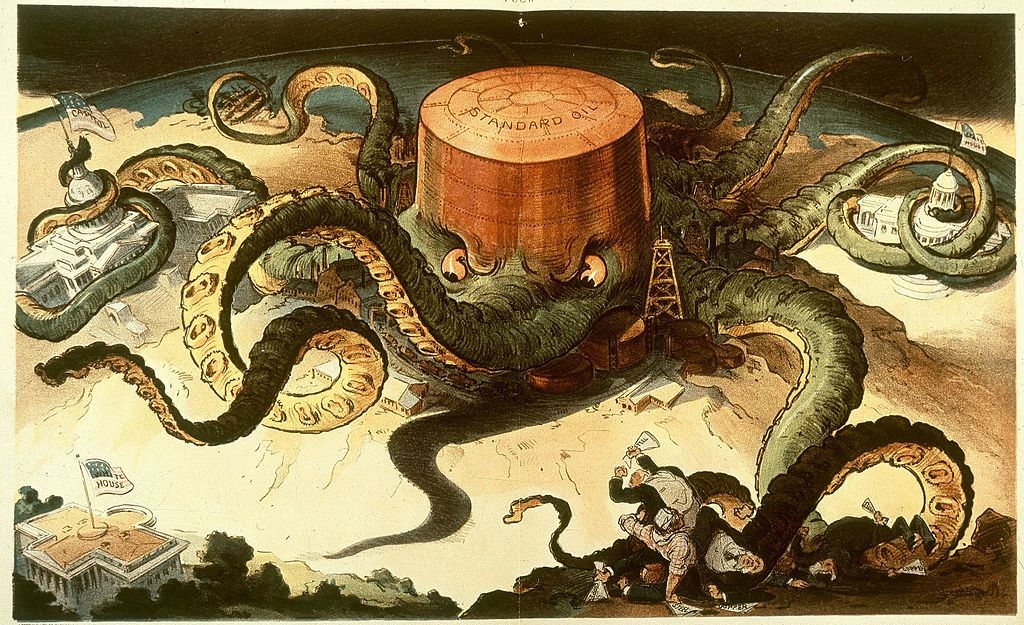

The ideological arc is to be expected in contemporary right-wing American politics. It is “the common man v. the elite” which is the Punch and Judy show of Fox News’ opinion programming and the related media infrastructure. In particular, Hawley positions himself as Teddy Roosevelt taking on the massive corporations of the early 20th century and technology companies as the descendants of JP Morgan.

The core intellectual elements of Hawley’s ideology concern an opposition to what he calls “corporate liberalism.” This interlocutor is not well defined, except that it seems committed to the libertarian idea that businesses should largely be unencumbered by intervention. Historically, there’s some precedence for calling this view “liberalism,” but in Hawley’s context, it’s a choice that seems tailor made to avoid the admission that the staunchest advocates of this position are the modern GOP.

While “corporate liberalism” is the name that Hawley gives the interlocutor, the actual substance of the position is much more mundane. It seems that Hawley’s principal objection is to any ideology that centers power structures too much. Hawley’s “republicanism,” such as it is, seems to be oriented to the traditional idea of individual independence from overbearing governments or corporations. In theory, this idea may be palatable to some readers; certainly, the idea that each individual ought to have autonomy, not have their choices influenced any more than is reasonable, is something that appeals to many Americans. Hawley’s main project is trying to move that from the naïve libertarian economic policy to a more protectionist ideology.

The only genuinely interesting thing about Hawley’s book, in my estimation, is that it illustrates a deep philosophical tension in the modern American right: the language of the culture wars is fundamentally incompatible with the economic policies of opposing regulation and cutting taxes for the most successful businesses. Hawley does his best to avoid this tension, but unlike many of his cohorts, the fact that he’s chosen a fundamentally regulatory issue as essential to his identity makes limiting that discussion impossible. At some points, he’s railing against tax breaks provided to Apple and Amazon that are core to the Republican Party’s economic identity and (perhaps most importantly) its fundraising pitch to donors.

Cynicism and ideological incoherence

This starts to shift us towards the most cynical element of Hawley’s book, one that I think is especially important when talking about the politics of contemporary technology and the prospects for any technology regulation that would be put before a legislature. The cynicism centers on one point: Hawley is very particular about which companies are at issue. His book picks out five companies: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter. His most specific and lengthy discussions focus on Facebook and Google, but all five of these companies see significant critique and they seem to be the core of the cartel that Hawley refers to as “Big Tech.” The challenge is that there are cases of technology companies which do the same thing, but which Hawley ignores because those companies are convenient allies and potential donors.

There should be no dispute that the five companies Hawley picks out have an absolutely absurd, destructive amount of power. They have built that power through consolidation of market share and at times carving up the market in ways which are anti-competitive. Google’s AdWorks has drawn investigation from the European Commission; Facebook has drawn lawsuits from both state governments and the FTC.

These are behaviors detrimental to the economic development of industry and allow for companies to engage in ethically abominable behavior (like the failure to adequately moderate extremist and even genocidal content, gross violations of user privacy, etc.) without concern of losing their business to competitors.

Hawley rightly acknowledges these problems. However, his understanding of these problems seems to apply only in cases where he regards the companies as cultural opposition. Hawley repeatedly notes “liberal bias” among the companies that he recognizes as Big Tech. But this only works because he picks the very narrow band of companies.

“Well,” Hawley might respond, “those just are the big technology companies in the United States.” But this is misleading, because it hinges on a very particular, gerrymandered conception of “technology” that includes some device manufacturers (Apple and Google) and some developers of digital infrastructure (Amazon), while systematically excluding others. Conveniently absent from Hawley’s analysis are a bunch of companies that are involved in exactly these processes, but are more closely aligned with Hawley on cultural issues.

The most grating example, as I was reading the book, is the regionalized telecoms cartel. Some of the companies that make up that cartel (like Comcast Corporation) fit under the umbrella of “liberal” in corporate liberal that Hawley is railing against. Others, like Consolidated Communications, are more sympathetic. Whether Hawley intends to insulate this particular cartel, while attacking the social media cartel of Facebook, Twitter, and Google, is unclear. Similarly, his points about the use of this infrastructure to engage in political manipulation fall extremely flat when one recognizes that the arguments he employs apply to broadcast companies like Sinclair and Fox just as easily as they apply to Apple.

Hawley’s criticism of corporate power is reasonable, and his endorsement of antitrust policies to break the cartels up is a potentially interesting (though far from adequate) proposal. The substance of how that would work is under-developed, and the last chapter is cribbed from the interesting work of Yale’s Dina Srinivasan (material far more worth engaging directly than through Hawley’s thin regurgitation of it). The criticism becomes unreasonable when one sees the special pleading Hawley engages by limiting the focus of those proposals merely to the technology companies he doesn’t like, rather than applying them broadly to the range of ISPs, device manufacturers, and content platforms.

The problem is that Hawley stakes these positions out as a core tenet of his civic ideology, that companies should not have too much control over consumers, should not be able to unduly influence consumers, and certainly should not actively misinform them. This is largely the language of the socialist left in America post-Occupy Wall Street and has roots back to the anarcho-socialist movements of the early 20th century.

My most charitable reading of Hawley’s ideology is that its best moments are the tenets of political philosophy that it shares with modern anarcho-socialists. These claims are as follows:

- There is no meaningful distinction between an overbearing authoritarian state and an overbearing authoritarian private ruling class.

- The principal role of social organization should be in service to the “common man,” where the “common man” is understood in terms of labor.

- Prohibitions on the accumulation of capital and the use of that capital are necessary in order to better ensure that social organization serves the common man.

- Interpersonal relationships of individual community members should not be mediated by private capital, but rather should be personal, private, and protected.

This is not to say that Hawley is anarcho-syndicalist. As noted above, his ideological commitment to these principles is hardly applied consistently. It is focused only on the five technology companies that he enumerates, and not to telecommunications companies, agribusinesses, banking, and the like. It’s only about his particular, present targets.

The politics of grievance

Hawley’s political views are also colored by a sense of grievance, that one of the consequences of the power of these social media companies is the political slant against Hawley’s preferred, right-wing views. Hawley insists that Republican politicians and media figures are being silenced, by the explicit policies of content moderation and by softer, less-visible power of deprioritizing content of right-wing views. While Hawley is quite insistent on both of these points, his arguments in both cases are specious. The latter is obviously nonsense, as those who study the top performing posts on Facebook (for example) routinely note that the top performers are overwhelmingly right-leaning (Ben Shapiro and Dan Bongino, in particular, are especially dominant in those analytics).

The purpose of both is to play the victim, though this deteriorates on a closer inspection of Hawley’s description of events. Is it the case that Twitter and Facebook removed Donald Trump’s accounts because of the events of 1/6, when all Trump was doing was insisting that the GOP engage in the appropriate certification process? These are the attempts at narrative creation where Hawley is clearly just pandering to those who already agree with him.

Even the pretense of a serious examination is not possible for the substantive proposals that Hawley lays out in the book. These proposals are often nebulous, and the devil would be deep in details that Hawley does not provide.

Hawley insists that Congress could legislate a “Do Not Track” button for social media sites that would allow the site to only gather user information that is “essential.” It’s not remotely clear what “essential” would mean; would it include cookies? Metadata on past interactions? Subscriptions to news sites? Information publicly displayed on a user’s page? Analytics regarding link performance? None of this is clear.

Similarly, he insists that websites could require verification of identity, though this would require social media companies to dramatically increase the amount of personal data that they gather and store (contra Hawley’s stated goals), and it’s not actually clear how such verification would be provided. There are a ton of logistical problems (like the fact that these companies service users around the world, and allowing individuals to set up accounts this way).

He lacks basic understanding of how things like open source technologies and cryptocurrencies work, so it is unsurprising that the proposals lack detail. His proposal for Sec 230 reform is only slightly less ridiculous than outright repeal, and it seems his major goal is actually just forcing Facebook and Twitter out of their existing models for monetizing (which would probably result in a subscription cost).

His principal insight seems to consist in the acknowledgment that Congress could empower the Justice Department to take a more active regulatory role. This is a good idea, that there should be some organization with legal authority and resources to engage in regulatory oversight, however there needs to actually be some substance to the regulations with which such an organization would be charged to enforce.

Broad-strokes proposals can be either devastating or toothless, neither of which is a desirable outcome. Destroying the revenue model for Facebook and Twitter would require them to transition to a different revenue model or go out of business, which would be devastating for those companies (and not great for users who are dependent on those products). Alternatively, presenting an overly general regulation restricting only “necessary” data would make the law impossible to enforce without spending millions of dollars litigating what data is necessary and hashing out other details, a cost burden that would ultimately favor large companies over their smaller competitors.

One necessary component for addressing data privacy is to specify both the kinds of data that companies are allowed to collect and carefully laying out conditions for storage and use. A useful illustration for such law can be found in the (commonly misunderstood) HIPAA privacy statute. First, HIPAA’s privacy statute specifies the companies that are covered by the suit; for the purpose of a data privacy law, we would want this to cover a broad range of companies (social media platforms, internet and phone service providers, web browsers, etc.) but it would be important to specify the scope of such a law.

In HIPAA, there are also clear requirements on storage of protected health information and conditions for sharing that information, requiring that any sharing of the information either has to anonymize the data or get user disclosure. One of the problems with the existing big data infrastructure is that large enough data sets become identifying, and so a law addressing such anonymizing processes must be more specific than even HIPAA is, reducing the amount and kind of data available to trade in order to prevent the large data sets from becoming identifying.

Hawley’s “Stop Collecting Data” button is a cute idea in the context of a stoned dorm-room discussion. It’s not a practical solution in the context of internet services that need to gather data to function. The amount of data a web browser needs in order to function, and the amount of data that websites would need in order to be financially viable on advertising models, makes the process of figuring out what counts as “necessary” data gathering complicated. Anonymization is one way to potentially address the issue, separating portions of the data sets into tranches such that the web browsers and websites collecting cookies have enough data to function, but are prohibited from sharing enough that it would violate user privacy. There are technical details here, and those details matter, but partitioning approaches are more useful and are parasitic on existing technologies which block some browser and website functions but not others. (If you use a browser based on open source technology, like Chrome, then you can actually use a range of plugins to create this effect. All we would be doing is making it mandatory for browsers, and for social media sites to accommodate this approach as well.)

These details are especially important because many people (Hawley included) also want to ensure that there are some age-based restrictions on digital activity. Hawley wants users to verify their identity when setting up a Facebook account. Doing so would legally obligate Facebook to dramatically increase the amount of information that they gather, and would dramatically increase the sensitivity of that information by making it directly tied up with governmentally specified information. If one wanted to take this approach (or perhaps something weaker, like age verification on in-game purchasing on mobile games, preventing children from spending hundreds of dollars on purchases through their parents’ devices), then doing so requires really careful specification of how this data can be used and stored. It also requires taking seriously potential security risks, as companies storing that data would then also have to store it in a way which is secure enough to protect the users.

Similarly, there has to be clarification of what powers the Justice Department or relevant regulatory agencies would have in overseeing these technology companies. Can the Justice Department require social media companies to turn over private information? This might jeopardize the civil liberties of users, and such issues have come up frequently in cases where the Justice Department has asked technology companies for protected information on customers. Giving the Justice Department oversight powers regarding those companies creates perverse incentives in regulation, where the Justice Department could unduly use regulatory power to acquire private information. (This is a version of the long-discussed worry about requirements of law enforcement backdoors for devices, and the potential security issues there.)

I have said all of that and all it does is to gloss one particular facet of these issues (namely information security). The purpose here is to illustrate the relative complexity of these policy issues and the inadequacy of existing, oversimplified proposals in the public sphere. These are important problems and they require more careful thinking and pragmatic politicking than may be possible in our present environment.

Featured Image is Next! by Udo Keppler