Justice Breyer's Misguided Institutionalism

Liberal Justice Stephen Breyer has served on the Supreme Court for almost 27 years. He is 82 years old. Right now, there is a Democratic president and a Democratic Senate. That means this is his chance to retire and be replaced with a justice who broadly shares his values, and will vote to protect abortion rights, LGBT rights, civil rights, and voting rights. If Breyer does not retire now, he, like Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg before him, is likely to see his replacement chosen by a fascist clown like Donald Trump. That would imperil his legacy and, indeed, democracy.

Yet, Breyer is signaling that he will not retire. He is releasing a book about the dangers of making the court a political institution, and observers believe he may stay in office to show that judges are not partisan, and do not care which president replaces them. “My experience of more than 30 years as a judge has shown me that, once men and women take the judicial oath, they take the oath to heart,” he declared in a Harvard Law School address. “They are loyal to the rule of law, not to the political party that helped to secure their appointment.” He added, “If the public sees judges as politicians in robes, its confidence in the courts, and in the rule of law itself, can only diminish, diminishing the court’s power.”

Breyer is worried that the appearance of a political court will erode public confidence and faith in democracy. For him, the main problem facing American liberal democracy is partisanship. But he’s wrong. The main problem facing American liberal democracy is fascism. And insisting that the fascists and opponents of democracy are good-faith partners in bipartisan defense of democratic institutions is the quickest path to destroying those institutions for good.

It’s important to point out that Breyer is wrong about politics and the judiciary. Courts in general, and the Supreme Court in particular, are obviously and openly partisan. Supreme Court justices are appointed by politicians, and they weigh in constantly on political matters. The Supreme Court decided the 2000 election when the five Republican appointees outvoted the four Democratic appointees and put Republican George W. Bush into the Oval Office. More recently, Justice Anthony Kennedy timed his retirement so his successor would be chosen by Republican Donald Trump, and then used his influence to get Trump to choose his former clerk, Brett Kavanaugh, as his successor.

More, the court shapes democratic institutions in ways that have a huge effect on partisan outcomes. In 2013, the conservative majority on the court gutted the provision of the Voting Rights Act that required many Southern states to clear voting changes with the federal government. The law was intended to protect Black voters, who generally cast ballots for Democrats. When it was abandoned, states like North Carolina quickly passed provisions intended to make it harder for Black people to vote. Similarly, conservative majorities have refused to block partisan gerrymandering which Republicans have used to give themselves unbeatable legislative majorities in states like Wisconsin. At a time when Democratic policies are more popular, and Democrats have solid national majorities, Republicans have fought back by trying to rig the system in their own favor so majorities no longer win elections. Conservative courts have helped them do that.

The dynamic here is straightforward; conservative courts buttress conservative legislative efforts to tip elections to conservatives. Breyer is able to read the same news stories and analysis I do. So why doesn’t he see it?

The answer is that he’s deliberately looking in the wrong place. The tell is in his concern that an appearance of excessive partisanship will “diminish the court’s power.” There are many things to worry about in our democracy right now. But no one I’m aware of seriously thinks that the Supreme Court’s authority is eroding, or that if it did it would be a major blow to democracy or to quality of life in this country.

But for Breyer, the influence and image of the court is of primary concern for obvious reasons; it reflects on his own influence and image. The vision of wise elites handing down the law is more rarefied than a vision of judges as part of a messy political coalition. Parts of that political coalition haven’t even gone to law school! For Breyer, the court has more power and status when justices ally first and foremost with each other.

As this indicates, powerful people tend to be comfortable with the status quo that gives them power. They are slow to acknowledge crises and change. You can see this in Democratic West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin’s current approach to voting rights legislation.

Again, Republicans are actively working to reduce voting rights across the country. In extreme cases they are even passing provisions that will allow GOP officials to simply overturn elections when Democrats win. Yet, Manchin says that he will only support voting rights legislation to restrict Republican power grabs if he can get 10 Republican senators to support it and overcome the filibuster. It’s like Neville Chamberlain insisting that Hitler was negotiating peace with honest motives. Better the end of the world than admitting that your colleagues in power sincerely want to destroy you.

Manchin and Breyer care a lot about those colleagues. The nice way to say that is that they are institutionalists. What that means stripped of euphemism is that they would rather be accountable to Mitch McConnell and John Roberts than to you or me.

The founders, too, were powerful white wealthy men, leery of accountability to the public. They built into the Constitution barriers to democratic influence. Some of these—disenfranchisement of Black people, indirect election of Senators—have been removed. Others, like lifetime Supreme Court appointments, remain.

Republicans have worked hard for decades to exploit weaknesses in our democracy which reduce accountability—whether that means using procedural maneuvers to prevent the democratically elected President Obama from placing a justice on the Supreme Court or trying to get state officials to refuse to certify votes. Democrats have generally tried to stop them.

But people in power, of whatever party, also have strong incentives to dislike accountability. That’s why calls for bipartisanship often mean, in practice, “We rulers can all agree that we should be insulated from public pressure.”

When Breyer denies the role of politics on the court, what he actually is doing is taking sides with the party that doesn’t want its members to be subject to the will of the voters. In the US today, that party is the increasingly anti-republican Republican party. We are rapidly reaching a point in the United States where the choices are Democratic partisanship or fascism. If Breyer eschews the first, he is by default paving the way for the second.

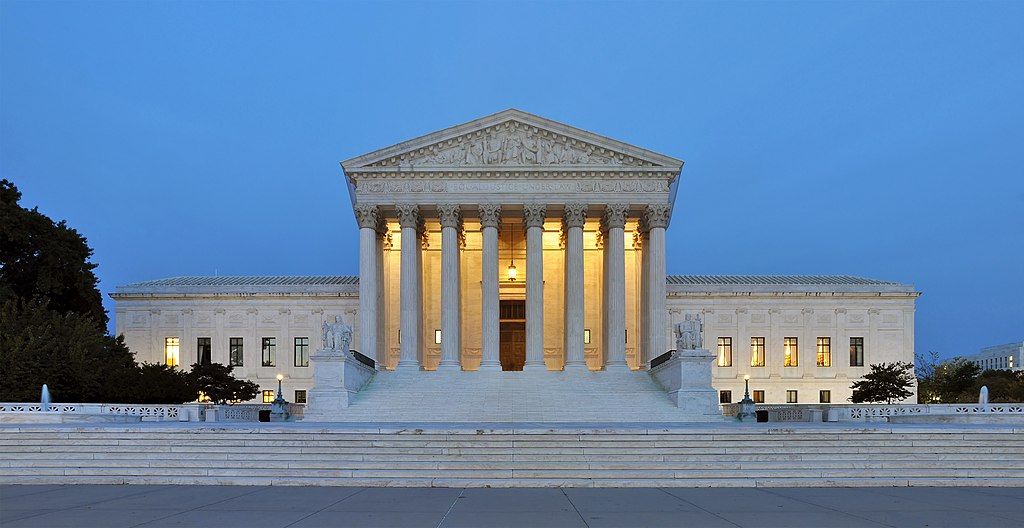

Featured Image is Panorama of the west facade of United States Supreme Court Building at dusk, by Joe Ravi