Liberalism versus Reaction in Ayn Rand

We are as gods and might as well get good at it. – Stewart Brand, Whole Earth Catalog

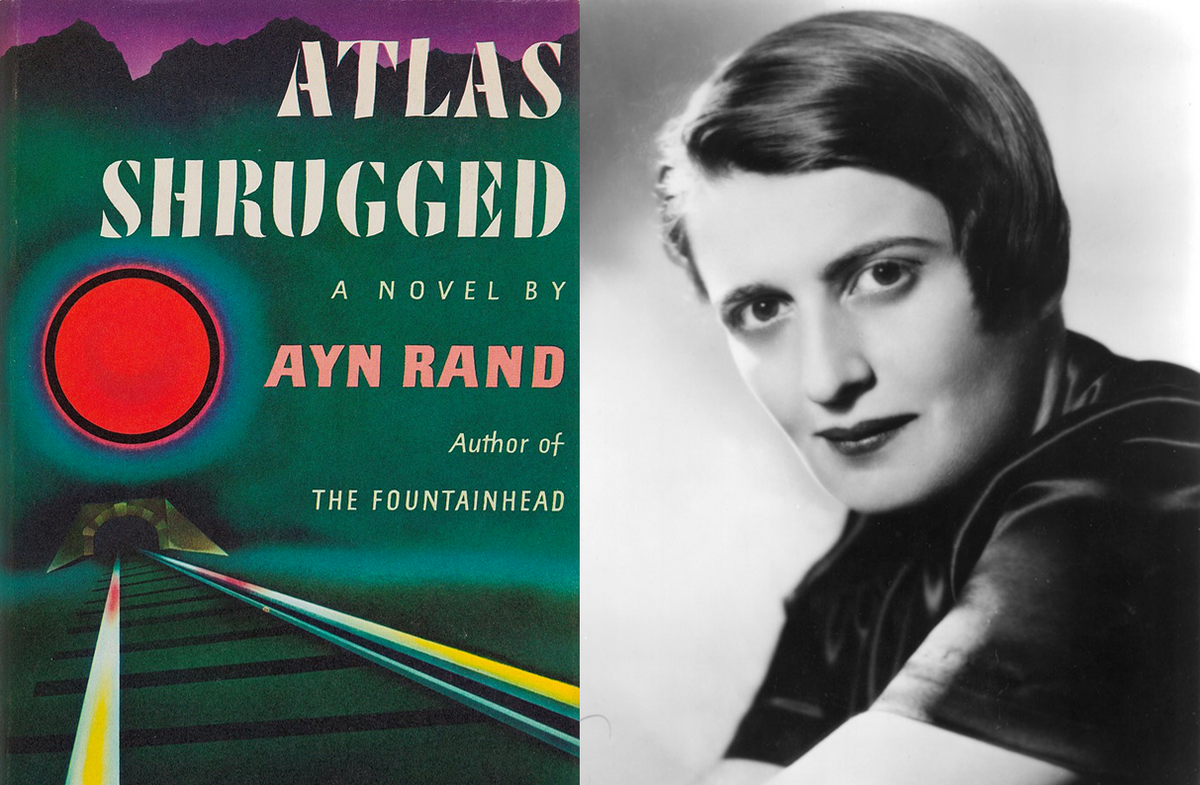

Ayn Rand was a brilliant, inventive thinker whose contributions go largely unsung outside libertarian circles. Rand developed a secular eudaimonist ethics decades before the 20th century revival of virtue ethics ignited. She pioneered a thick ethical and aesthetic defense of capitalism that celebrated business and innovation as heroic; her frontal assault on altruism represented a fundamental shift away from defending economic freedom under the pall of suspicion of the profit motive. She erected a philosophical permission structure for rational self-interest, achievement, and the pursuit of happiness.

Rand forged a synthesis of possessive and expressive individualism and fashioned a perfectionist political doctrine of truly human flourishing, sweeping away the Marxist monopoly on such rhetoric and anticipating its reemergence in the capabilities approach by several decades. She promised a vision of human possibility, progress, and triumph over limitations that boldly assumed that we are indeed as gods, and that the greatest threats to our future are philosophies prioritizing impossibility, failure, and weakness.

Rand achieved all this as a refugee from Soviet Russia by way of a couple of gripping, wildly successful philosophical novels that cast rail networks and steel production in romantic glory. She launched a movement that rocked conservative politics, shaped the nascent libertarian movement, and is still going strong some four decades after her death.

I’ll have several sharply critical things to say about Rand in this essay, which explores how her philosophy of Objectivism relates to the liberal tradition. Indeed I’ll question whether Rand really belongs within the liberal tradition at all, as several aspects of her thought reveal an illiberal, even reactionary hue. For whatever harsh words follow, I maintain that Rand was an ingenious thinker and a talented novelist who deserves respect and sympathy. Despite the doubt I will cast on Rand qua liberal and indeed qua social thinker, I will conclude by sketching what a liberal and genuinely emancipatory Objectivism might look like.

Rand and the politics of liberalism

Rand is usually seen as one of the pillars of the modern classical liberal tradition. For libertarians, famously, “it usually begins with Ayn Rand.” Yet at a time when some major political parties in the world’s liberal democracies, once so comfortingly colonized by liberal habits, are flirting with or openly endorsing antiliberal values, it’s worth reevaluating foundational assumptions. It is in that spirit that I explore points of tension between Rand’s philosophy and the liberal tradition, and argue that she is better understood as a heterodox conservative.

I’ll set the stage by specifying what I mean by liberalism and its alternatives. Liberalism is an approach to politics that seeks to defuse, redirect, or even harness conflict in a society of reasonable individuals who differ in beliefs, backgrounds, and concerns. At minimum, liberalism holds to some level of representative government with genuinely open elections, basic freedoms of religion, speech, assembly, and commerce, and a tolerance for internal pluralism and diversity. Liberalism stands explicitly against absolutist power, in the form either of monarchies or totalitarian communist regimes, among other possibilities. Its closer (and overlapping) neighbors are socialism—which weakens or opposes the sanctity of commerce and in its extreme forms undermines the other liberal desiderata in order to empower the working class—and conservatism—which tends to weaken pluralism and the freedoms of minorities and in its extreme forms compromises representative government and the rule of law to favor a preferred racial or religious group.

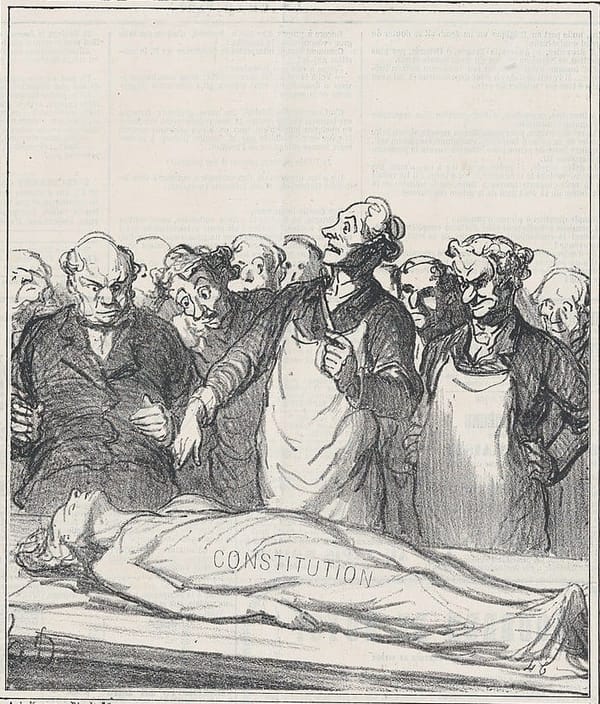

Rand advances a comprehensive doctrine, Objectivism, that sits uneasily with the political liberalism of democratic authority. Rand’s idealist views of the history and meritocracy of capitalism naturalized traditional hierarchies and justified contempt for the poor and marginalized. While Rand despised religious faith and thus the traditional religious authority much of conservatism appeals to, in her own life she thought of herself as on the political right, focused most of her rhetorical fire against the left, and exemplified a kind of reactionary anti-leftism. Rand’s illiberal conservatism—however heterodox—is showcased with particularly stark clarity in her epic masterpiece, Atlas Shrugged, in which a vanguard party engineers a total social and economic collapse to pave the way for a society ordered according to Objectivist values.

The role of comprehensive worldviews in a pluralist society is one of the perennial sources of tension in liberal thought. So-called liberal neutrality requires that a government favor no comprehensive doctrine over any other. But some comprehensive doctrines (like Catholic integralism) require that society be reshaped in their favored mold; some doctrines simply don’t play well with others. Rand insisted, even in her nonfiction, that there can be no conflicts of interest between individuals whose interests are rational. This idea first appears in Atlas Shrugged at steel industrialist Hank Rearden’s trial for violating regulations on the use of Rearden Metal.

“Are we to understand,” asked the judge, “that you hold your own interests above the interests of the public?”

“I hold that such a question can never arise except in a society of cannibals.”

“What . . . what do you mean?”

“I hold that there is no clash of interests among men who do not demand the unearned and do not practice human sacrifices.”

Rand, represented here by Rearden, goes beyond the belief that people may be mistaken or taken in by erroneous ideologies. She instead introduces the idea that a clash of interests must involve error or evil. Where bog standard political liberalism assumes innocent conflicts of interests and a boisterous polity of worldviews in tension with each other that must be managed for the sake of peace—or in a stronger vein, this diversity actually provides greater resources for solving social problems—in Rand’s Objectivism some party must be illegitimate. If, as Rand insists, any compromise of good with evil only profits evil and some party of every social conflict is evil then the idea that disagreement should be settled by elections is abominable. Democracy is by necessity a handmaiden to evil.

In Atlas Shrugged democracy is entirely sidelined. The plot follows the quickening erosion of economic freedom and its replacement with an economy of political threats and favors. All of the politics in the novel takes the form of corrupt, backroom deals between dishonest businessmen, lobbyists, political hacks, and ultimately economic czars of one kind or another. Rand’s virtuous heroes stay above this fray, and struggle valiantly to conduct ordinary business in an increasingly hostile environment. Importantly, Rand’s heroes really are virtuous: incorruptibly honest, just, hard-working, dependable, and even benevolent. The novel explores how such virtue is punished in statist economic regimes, those that fall short of laissez-faire capitalism.

While there is a legislature, an executive, and legal courts, there’s no mention of democratic elections or formal political parties (though there are factions). In So Who Is John Galt, Anyway? Objectivist commentator Robert Tracinski suggests this absence of the expected democratic institutions is because they had already been swept away in political turmoil prior to the main events of the novel. But this is unsatisfying. Such a cataclysm would surely leave marks on the main characters who would have ample reason to reference it. And if Rand’s heroes simply ignored the political world—wholly engaged as they were in their productive toil—until the looters’ government bore down on them, then this would reveal culpable negligence.

Rand conveniently includes a perfect being in Atlas Shrugged, John Galt, whose philosophical determinations and emotional reactions are beyond reproach. In the momentous scene at the heart of the novel that sets in motion Galt’s strike of the “men of the mind” there is no mention of prior or present political activism. Voting is rarely mentioned throughout the novel, and when it is it’s usually denigratory, as in Galt’s speech where he accuses his misguided audience of “[voting politicians] into jobs of total power over arts you have never seen, over sciences you have never studied, over achievements of which you have no knowledge, over the gigantic industries ….”

Objectivists may think that honest business people shouldn’t have to be bothered with politics, but this reveals the problem with Rand’s conception of no rational or innocent conflict of interest. Good, rational people simply do see the world from different angles and come to different conclusions, and democratic politics is in part about managing these differences peacefully. When this essential vice of disagreement is coupled with the extreme conclusions of Rand’s political philosophy—such as that taxation is theft and all regulation of business violates the prohibition on the initiation of force—the entire range of normal democratic politics is rendered illegitimate, vicious, and evil. This weakens any hold normal liberal democratic politics has on the Objectivist and frees them from any restraint of perspective.

This antidemocratic element in Rand’s thinking finds its fully antiliberal expression in Galt’s Gulch, where Galt’s strikers—Rand’s heroes—decamp to withdraw their productive capacity from society, watch it collapse, and prepare to reenter society on their own terms. Rand scholar Chris Matthews Sciabarra notes in Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical that Galt’s Gulch is effectively organized as an ideological commune, with every person adhering to the same belief system, obviating both politics and government. But this misses the planned hostile takeover of the outside world. The strikers are not passive communitarians engaging in some kind of Benedict Option, but vanguardists specifically seeking to overthrow the current regime. Ostensibly, this vanguardism is nonviolent, but the strike is effective only in Rand’s fantasy worldbuilding, wherein the removal of a thousand or so of the most talented industrialists, engineers, and capable people of all kinds would reduce society to a state of total dysfunction, literally unable to keep the lights on.

I must note here that in her actual life, Rand participated avidly in democratic politics, campaigning for (Republican) candidates and encouraging her followers to vote in certain ways. So Rand’s no-compromise-with-evil position never took the antidemocratic, anti-voting turn popular among some Marxist-Leninists and anarcho-capitalists. So it’s certainly possible to be an Objectivist and still be a small-d democrat. My purpose here is to explore the tensions between Objectivism and liberalism, which sometimes but not always result in illiberal politics.

Ayn Rand: the unknown ideal theorist

Rand sits uneasily with the liberal idea of inescapable political conflict and democratic politics. But how could Rand be a conservative when she opposed the religious right, fiercely defended the right to abortion, and was an outspoken atheist who condemned religious faith? Rand’s philosophy is on the surface quite liberal. Her own vision of capitalism was one of progress, openness to new ideas, and an openness to strivers from all backgrounds to test their mettle in the market and strike it rich.

Rand’s critics who assume she merely shilled for the rich and business interests face an awkward set of facts. Most of Rand’s villains in Atlas Shrugged were wealthy businessmen, her heroes all discard or destroy their worldly riches, and her ideal man, John Galt, was a manual rail laborer.

At times Rand goes out of her way to admire the quiet, modest dignity and competence of the regular laborer. Track workers saluting Dagny Taggart, Rand’s rail heiress protagonist, and cheering the initial run of the John Galt Line is a notable example of this, and it’s paralleled by the good relations both Rearden and Francisco, Rand’s ultra-capable and flamboyant copper industrialist, have with their respective employees.

The first main character we meet is Eddie Willers, a decent man and ally of Dagny and unwitting confidant of Galt, but no übermensch. Cheryl Taggart, Dagny’s sister-in-law and a victim of Jim Taggart’s psychopathic need for warrantless love and praise, provides an example of a simple store clerk discovering the values of Rand’s heroes. Rand gives at least two redemption arcs, in the railroad tramp Jeff Allen who Dagny deputizes in an emergency, and in the “Wet Nurse” sent by the government to spy on Rearden who is converted to Rearden’s cause and values.

Rearden rose from unskilled, dangerous work in ore mines as a teenager to owning his own steel mills and even inventing a lighter, stronger alloy. Such rags-to-riches stories are to be expected in Rand’s capitalism. But so is the obverse. In his famous money speech, Francisco argues that those who are born rich must eventually fritter away their wealth if they are incompetent. This is the morality of capitalism: ability and hard work are rewarded and sloth and venality are punished. To the extent capitalism fails to match Rand’s vision, it’s because we mix capitalism with socialism in a mixed economy. Rand associates the explosive innovation and productivity of the 19th century with the relatively purer capitalism of that era.

In its ideal form, Rand’s capitalism embraces liberal equality and universalism. It is color-blind, recognizes equal rights for women, and is open to ambitious, freedom-seeking immigrants (like Rand herself). Dagny is a capable, confident woman thriving by her own lights in a man’s world. In what might be viewed as an early manifestation of sex-positivity, Dagny knows what she wants in love and sex and is undeterred in pursuing her sexual ends on her own terms, which incidentally never involves marriage.

Reaction by sleight of hand

Rand in practice differs markedly from her ideal theory. In the end she does endorse many traditional values. But her conservatism assumes the form of an orientation toward upholding extant social hierarchies. Rand’s capitalism is free and equal in the ideal, but by a rhetorical sleight of hand Rand in practice naturalizes and romanticizes hierarchy in a way that neatly maps onto existing social strata.

In tension with the respect she sometimes shows for workers, Rand’s heroes frequently show contempt for the poor. An early example of this is when Dagny measures herself against both her peers and the adults around her and notes the “regrettable accident” that she is “imprisoned among people who were dull.” Later she contrasts normal people with her fellow superlative, Rearden.

Watching him in the crowd, she realized the contrast for the first time. The faces of the others looked like aggregates of interchangeable features, every face oozing to blend into the anonymity of resembling all, and all looking as if they were melting. Rearden’s face, with the sharp planes, the pale blue eyes, the ash-blond hair, had the firmness of ice; the uncompromising clarity of its lines made it look, among the others, as if he were moving through a fog, hit by a ray of light. (Emphases added)

Note the physical differences between Rearden and others under Dagny’s gaze. Rand persistently associates physical attractiveness with superior capability and moral uprightness throughout Atlas Shrugged. Capability for Rand is a singular value; in what might be considered a tension with another liberal tenet—the division of labor—Rand’s heroes are good at anything and everything they do. Where ordinary people are often portrayed as untalented and unmotivated about whatever job they find themselves in, Rand’s superlatives can farm and sew with the same elite skill they apply to their chosen profession.

By strongly associating—if not exactly equating—attractiveness, capability, and morality, Rand naturalizes hierarchy. This association becomes all the more alarming when we consider that all of Rand’s heroes are white, most of them blond. There is something essential within heroic individuals that fundamentally sets them apart from normal folks, just as Dagny surmised at age nine. Of course there are some rags-to-riches cases in actual capitalism. But this is far from the norm, and contra Francisco’s faith that fools and their money are soon parted, phenomenally venal and incompetent people—think Donald Trump—are born to wealth and live their lives in luxury and power as their wealth maintains itself on autopilot.

While ordinary folks are not always contemptible, they are always expendable in Atlas Shrugged. The non-superlative but ethical characters discussed above—Eddie, Cheryl, and the Wet Nurse—all meet grisly fates. The strike of the “men of the mind” is itself the prime example of the expendability of the mediocre, as millions die or are brutally impoverished (though it’s worth considering how many children are victimized by the strike who may have grown into superlative adults). It was part of Rand’s romantic vision that none of the denizens of Galt’s Gulch ever died or suffered serious misfortune. Rand insisted that pain, fear, and guilt should not be taken as primary. But lesser characters, like real world mortals, don’t have this plot armor, and have plenty of reason for fear.

Rand insists that real capitalism has never been tried, and capitalism à la Rand really never has existed, but this doesn’t stop Rand from appealing to the meritocratic and productive properties of ideal capitalism to defend actually existing capitalism. This creates a perilous discursive situation in which Objectivists can with suspicious convenience attribute all the good results of modern mixed economies to capitalism and all the bad results to the failure to adhere to Rand’s precise specifications.

In practice this constitutes a justificatory algorithm for defending the esteem of anyone who is rich—and the legitimacy of their wealth whether it was acquired by inheritance, implicit or explicit government transfers, or Herculean effort and Promethean innovation—and blaming the poor, regardless of their circumstances. Rand thus defended the upper classes from incursions by the lower orders in both theory and in practice, and Objectivists have followed her lead.

Despite Dagny, Rand affirms patriarchal values. Rand believed it was a woman’s purpose to worship a man who embodied her greatest values. She believed there would be something sinister about a woman ever being President because such a woman would be betraying her feminine nature. For all Dagny’s assertiveness and capability, she is the only female titan of industry, and even in Galt’s Gulch there appear to be few women, most of whom remain unnamed and have come to join their menfolk. Dagny’s sex-positivity must be understood alongside Rand’s persistent slut-shaming, as when Francisco lectures Rearden that he can tell everything about a man’s values just by seeing the woman he sleeps with.

Rand is untroubled by sexism and misogyny. In an early throwaway exposition Dagny dismisses sexual prejudice and casually resolves not to consider it again. Perhaps Rand envisaged a world without misogyny. Indeed Dagny receives no abuse, denigration, or lowered expectations from men in a book littered with scenes of otherwise all-male board rooms. Yet if that’s the case, we’re left with the troubling question of why Rand’s fiction isn’t peopled with more women like Dagny. The ready answer is that women aren’t natural leaders or innovators.

In real life women cannot shrug off sexual and domestic violence, discrimination and harassment in the workplace, objectification, and non-remuneration of reproductive and domestic labor as easily as Dagny can. In her nonfiction and her public comments, Rand loathed feminists, even referring to herself as a male chauvinist. Firmly supporting the right to abortion on grounds of bodily autonomy, though laudable, doesn’t absolve her of her traditionalist views about women’s roles or her reaction against social movements to liberate women from those roles.

Rand averred that homosexuality was immoral, the result of psychological disorder, even “disgusting.” Needless to say there’s no distinction between sex and gender for Rand, and these are strictly binary. The government has no role in enforcing sexual values, but gender and sexuality are a site of judgment, with nary a presumption of innocent difference or respecting human diversity. In Atlas Shrugged Rand evades the problem of gays, lesbians, and transexuals by—blank-out—simply leaving them out of her world-building. In the real world, homophobic and transphobic rhetoric supports narratives of non-Objectivist rightwing parties that do not so scrupulously refrain from force and fraud. This matters. Young Objectivists tend to think Rand was wrong about homosexuality but Objectivists generally endorse anti-trans talking points.

An epistemology of ignorance

Another tool Rand deploys for justifying hierarchy is an epistemic vice she decried in her adversaries: what the great liberal philosopher Charles Mills would dub the “epistemology of ignorance” but Rand named “blanking out.”

Thinking is man’s only basic virtue, from which all the others proceed. And his basic vice, the source of all his evils, is that nameless act which all of you practice, but struggle never to admit: the act of blanking out, the willful suspension of one’s consciousness, the refusal to think—not blindness, but the refusal to see; not ignorance, but the refusal to know. It is the act of unfocusing your mind and inducing an inner fog to escape the responsibility of judgment—on the unstated premise that a thing will not exist if only you refuse to identify it, that A will not be A so long as you do not pronounce the verdict “It is.”

Rand doesn’t discuss race at all in Atlas Shrugged, but omission speaks volumes. Slavery for Rand is usually a histrionic metaphor for the oppression of the industrialist. When she refers to genuine slavery in history, it’s the non-racialized slavery of antiquity, and it’s followed by an apparent denial of the racialized slavery of antebellum America.

That phrase about the evil of money … comes from a time when wealth was produced by the labor of slaves—slaves who repeated the motions once discovered by somebody’s mind and left unimproved for centuries. So long as production was ruled by force, and wealth was obtained by conquest, there was little to conquer.

[…]

To the glory of mankind, there was, for the first and only time in history, a country of money—and I have no higher, more reverent tribute to pay to America, for this means: a country of reason, justice, freedom, production, achievement. For the first time, man’s mind and money were set free, and there were no fortunes-by-conquest, but only fortunes-by-work, and instead of swordsmen and slaves, there appeared the real maker of wealth, the greatest worker, the highest type of human being—the self-made man—the American industrialist.

Rand blanks out slavery itself in a stunning hagiography of America, notes that she knows real slavery has existed in history and studiously blanks out race throughout the rest of the novel except when describing the white features of her heroes.

Rand’s history is no better when she engages race in her nonfiction, where she argues that “racism was strongest in the more controlled economies, such as Russia and Germany—and weakest in England, the then freest country of Europe.” There might be some truth to this if Rand judged 19th century America as unfree, but for Rand “in its great era of capitalism, the United States was the freest country on earth—and the best refutation of racist theories.” Rand continues,

It is capitalism that broke through national and racial barriers, by means of free trade. It is capitalism that abolished serfdom and slavery in all the civilized countries of the world. It is the capitalist North that destroyed the slavery of the agrarian-feudal South in the United States.

Such was the trend of mankind for the brief span of some hundred and fifty years.

Rand explicitly rejects the notion that some races have greater “incidence of men of potentially superior brain power” but her historical analysis reveals she viewed slavery and the oppression of Jim Crow as minor deviations from a system of full individual freedom.

In her essay on racism, Rand goes on to condemn Black leaders as racist for supporting affirmative action, compulsory school integration, and anti-discrimination laws on private establishments. Like today’s anti-anti-racists, Rand projects the notion of “collective racial guilt” onto whites for “the sins of their ancestors” for policies aimed at repairing racial inequities despite no significant Black thinker using such concepts, certainly not the specific activist Rand quotes in her essay. Such inequalities obtained, Rand recognized, on account of government policies, but Rand ignored or didn’t understand the extent to which the government continued to support racial inequality with policies like redlining, segregation, relative deprivation of public funds for Black communities, and a long laissez-faire approach to anti-Black terrorism. But even if, as Rand imagined, direct government racism had ended, a vast difference in life prospects would have remained for Black and white individuals. Rand’s just-so story in which racism is a minor problem and the graver threat comes from the redistributionist policies of anti-racists functions as an ideological bulwark against policies to promote racial equality, once again reinforcing the status quo socio-economic hierarchy.

In all these cases Rand instinctively defends the relatively advantaged and inveighs against the claims of the disadvantaged. Rand and her followers would claim that she merely defends individual rights, especially those of property, and does so in accordance with equality before the law. But this reactionary—a word Rand self-applied—kind of nominal liberalism erodes the rule of law in fact while upholding it in name. Liberalism cannot be collapsed into rights alone; there must be a dimension of political contestation. A highly hierarchical society that jealously guards property rights without real political contestation is not any kind of liberalism, but feudalism.

Consider the disproportionate violence inflicted on Black men by police. On its face this is a failure to uphold equality before the law, but if the resulting protests are successfully framed in terms of alleged looting of private property, then Objectivists will flock to the defense of the rights-violating police. In contrast to Rand’s version of the “great era of capitalism,” real people who are not wealthy white men have not enjoyed equality under the law. By aggressively objecting to alleged excesses of any appeal to social justice, blanking out historical evidence of oppression, and insisting the most legally and institutionally coddled classes are really the most oppressed, Rand undermines the civic equality of all persons.

Blanking out inconvenient truths combines with the antidemocratic elements of Rand’s political philosophy to brutal effects. The illegitimacy of actually existing governments renders the supposedly “objective” political theory subjective in practice. This enabled Rand to endorse deeply illiberal ideas, such as the right to invade “dictatorships”—what does this mean when all actual governments are illegitimate by her lights?—and the lands inhabited by “savages” who don’t share Rand’s concept of property rights (neither has America, ever). Yaron Brook, the erstwhile Executive Director of the Ayn Rand Institute, would take this reasoning further to condone torture and preemptive nuclear strikes. Rand adopted a kind of American exceptionalist outlook based not on the actual proximity of American governance to Objectivist doctrine, but to her biased views of America’s founding ideals and her largely imagined history of early American capitalism. Rand pitted America in theory against the rest of the world in practice.

Randian reaction today is expressed by befuddlement in the face of genuinely antiliberal, antidemocratic authoritarianism. I have no doubt that Rand would have condemned Donald Trump—he really is like one of her villains, only less believable—but it’s not at all clear she could have held her nose enough to support Democrats. The mere presence of democratic socialists like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the wings would likely have spooked Rand into a “pox on both houses” stance. Some prominent Objectivists today exhibit such both-sidesism, and even invite Trumpist figures like Peter Thiel to their galas.

Varieties of Randian liberalism

To recap, Ayn Rand is more fruitfully understood as a heterodox conservative than as a liberal, and is at best a rightwing liberal with illiberal tendencies. Rand advanced a politics of the good that viewed its ideological adversaries as fundamentally illegitimate. Her totalizing vision of the political order—however easily stated on one foot as strict laissez-faire capitalism—allowed her to be a kind of nationalist, an American chauvinist. Rand defended the rule of law in principle, but undermined civic equality in practice by promoting hierarchy and reaction.

To touch grass for a moment, of course Rand was a conservative, or at least a rightwinger. Rand saw herself as on the political right, was active in rightwing political campaigns throughout her entire life until the rise of Reagan, and is embraced almost exclusively by the political right. These claims aren’t controversial. My controversial claim is that Rand’s heterodox conservatism—especially as expressed in her magnum opus—has underappreciated tensions with liberalism (even of the classical variety) that sometimes slips into illiberalism.

It is not so hard for admirers of Rand to stay on the side of liberalism. It means firmly supporting democratic institutions and practices. Some Rand enthusiasts remain firmly liberal. Robert Tracinski is admirable in this. In academic philosophy, Douglas Rasmussen and Douglas Den Uyl have fleshed out a Randian liberalism that plausibly manages the tension between political liberalism and Rand’s perfectionism. Neera Badhwar lessens the tendency for Objectivism to view other ideologies as basically illegitimate.

Gestalt-shifting Rand

It’s no accident that Rand has many fans in gay and queer communities. It’s not unheard of even for some prominent progressives to signal appreciation for Rand, a recent case being Stacey Abrams. I attribute this to Rand’s celebration of individualism against the crowd, of triumph over adversity, and of joy in one’s own projects and self-directed life. These sentiments have cross-political appeal. The fact is, people will continue reading and finding inspiration in Rand because she was a fascinating and inspiring figure. It is thus worthwhile both for those dismissive of Rand to see what is valuable in Rand and for her enthusiasts to identify and jettison the illiberal elements of her philosophy. I end by offering an under-explored left Randian liberalism that I hope can serve as a bridge over the apparently impassable chasm separating Rand from social liberalism.

Rand’s exaltation of the innovative and productive powers of capitalism is shared by Marx and other socialists. Marx associated productive labor with the essence of human nature. The dimension of Rand that evokes the unfolding of human potential mirrors both Marxism and the expressivist left liberal branch of the liberal tradition stretching from Adam Smith through J.S. Mill and T.H. Green to the capabilities approach of Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen. Sciabarra recounts,

Peikoff … argues that at the core of Objectivism is a belief in the actualization of human potentialities. In this regard, Objectivism follows the Aristotelian conception of eudaemonia as the human entelechy. For Aristotle, the proper end of human action is the achievement of “a state of rich, ripe, fulfilling earthly happiness.” [Branden] argues that human life involves the expansion of “the boundaries of the self to embrace all of our potentialities, as well as those parts that have been denied, disowned, repressed.” The actualization of human potential is a form of transcendence, an ability “to rise above a limited context or perspective—to a wider field of vision.” This wider field does not negate the previous moments; it is a struggle “from one stage of development to a higher one, emotionally, cognitively, morally, and so forth …”

This provides the basis for a Randian left liberalism: securing the conditions for the free development of capabilities for all persons. This requires a reevaluation of certain empirics and a gestalt shift in how the demands of social justice are perceived. A move away from Rand’s categorical prohibition on the initiation of force to a more complicated limitation of coercion within the rule of law is also needed. A categorical non-aggression principle is a floating abstraction in a world characterized by pervasive historical injustice and complex social relations and institutions that persist over generations. Redistribution toward some base level of relational equality for all and effective capability to pursue one’s own flourishing is more akin to Rand’s philosopher pirate Ragnar Danneskjold’s liberatory antics than it is to kleptocratic predation.

Rand gets a number of facts about the world simply wrong. The reality of global warming is one of the least controversial examples. Objectivists deny global warming in defiance of a broad scientific consensus, perhaps because it is seen as a threat to capitalism. But the fossil fuel industry has feasted on subsidies, has an entrenched lobby for political pull, enjoys implicit advantages like the government embrace of suburbs and car culture. The fossil fuel industry hardly embodies laissez-faire capitalism. Pollution causes real harm and is best tackled not by courts and litigation, as Rand preferred, but by legislation and regulation, preferably by pricing in externalities.

There’s no intrinsic reason to glamorize Big Oil and its tycoons instead of Big Renewables and their own heroic scientists, engineers, and business leaders. Environmentalism is not, as Rand maintained, inherently anti-human or anti-development. The gestalt shift here is to see fossil fuel companies as villains clamoring for handouts (by not paying the full cost of greenhouse gases) and solar, wind, and nuclear companies as heroic innovators struggling against the odds to usher forth an era of energy abundance. Stewart Brand, whose epigraph opens this essay, combines just such a Randian vision for human potential with no-nonsense environmentalism.

Even orthodox Objectivists should accept this revision. But social justice issues are thornier because they directly challenge Rand’s reactionary tendencies. The extent, contours, and social and economic impact of sexual harassment and sexual violence is matter for objective study, one where perhaps feminists know whereof they speak. There’s little reason for Objectivists to categorically dismiss these concerns other than by slavish adherence to Rand’s prejudices.

Rand loathed feminists for making demands on the government, but the gestalt shift here is that the domestic and reproductive labor typically performed—unpaid—by women is socially necessary (wait til you see what a strike of the womb can do) and men feel entitled to the fruits of that labor. Patriarchy is rule by the moochers and looters of sex, care, and reproduction. Institutions to reward feminine-coded labor like subsidized child care and paid parental leave would engender a more consistent capitalist order, even if they are built upon a platform of social provision.

Philosopher Kate Manne persuasively describes patriarchy as a set of entitlements, and one of these entitlements is for women (and men in a roundabout way) to conform to a normative image and set of functions. The backlash against trans and nonbinary persons owes to the failure or refusal to conform to the patriarchal model. That’s it; there’s not even a significant demand for redistribution in the struggle for trans rights and dignity. But a Randian feminist sees trans liberation as a heroic refusal to perform gender on anyone’s terms but one’s own.

I already discussed above that Rand’s understanding of the history and legal reality of race in America is largely a fabrication. Objectivists who want to take individual liberty seriously should reckon not only with the profound unfreedom of slavery but with the persistent resistance to policies conducive to Black equality and Black flourishing. Objectivists imagine that the impediments of racism have largely been removed. The racial disparities in policing and incarceration suggest this is overstated. But the entanglement of race in American policies and institutions makes merely removing superficial impediments a deceptive goal. White Americans have been showered with political advantages, legal privileges, and asset-building handouts like the G.I. Bill, land grants, and preferential home loans that have enabled them to accumulate intergenerational wealth and disproportionate political power. Banning only public discrimination and doing nothing to repair the damages caused and permitted by the state constitutes a failure of the state to secure equality before the law. Rand’s idea that this is about collective racial guilt is defensive histrionics.

The gestalt shift here is that policies of Black flourishing are not special pleading for collectivist redistribution. They reverse more than two centuries worth of white collectivism and upward redistribution of wealth and esteem to whites. The white plantation owner should be seen as the most profound of Randian villains, along with the white legislator, the white prison warden, and the white NIMBY.

Securing the conditions for all persons to fully participate in capitalist enterprise is the lodestar of Randian left liberalism. To do this requires understanding that social justice is not collectivism but the appropriate, targeted response to the collectivism of white supremacist patriarchy. Just as Galt’s sense of benevolence and his desire to live in a free world prompted him to liberate his fellow heroes from an unfree system, we should likewise foster the conditions of freedom and abundance in which more heroic innovators will emerge. Though Rand may not have approved, this vision retains a distinctively Randian sense of life by celebrating achievement, damning genuine collectivism, and affirming the rational joy of the world where the rail lines merge.