Moderate Reformers and the American Administrative State: Jesse Tarbert's When Good Government Meant Big Government

Conservatives have long cast a suspicious eye on American government. They have questioned the efficacy and indeed, the constitutionality of the modern American state. Political debate surrounding the administrative state has raged within the courts, within Congress, and within the administrative apparatus of the executive branch itself. Pejoratively dubbed “the deep state,” conservatives have assailed “big government” as an affront to first constitutional principles. According to the orthodox historical narrative, Progressive reformers such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson advocated the expansion of federal administrative capacity to address the complications posed by the expansion of capitalism and big business. On the other side of the equation were conservatives such as William Howard Taft and Henry Stimson who opposed the expansion of federal power in favor of federalism. In short, it was conservative Republicans who opposed “big government.”

Jesse Tarbert’s new book When Good Government Meant Big Government complicates this narrative. Tarbert argues that—contrary to the orthodox narrative—it was a group of moderate to conservative “elite reformers” in the years between 1913 and 1933 who advocated the expansion of the federal government as a way to promote “good government.” These reformers, inspired by notions of corporate governance, advocated the empowerment of the federal government to efficiently govern the United States.

Tarbert’s narrative focuses on a group of reformers, among them Taft, Stimson, Warren Harding, and future chief justice Charles Evans Hughes. These men brought with them not the goal of shrinking the administrative state, but to make it efficient. They sought to empower the government to effectively execute national policy in response to burgeoning business.

Among the reforms advocated were a national budget and presidential reorganization of the executive branch. To these reformers, the ability to reorganize the executive branch was crucial because it allowed the president to shift bureaus and agencies to administer federal law more effectively. Scholars of reorganization generally focus on the New Deal and the work of the Brownlow Committee, but Tarbert builds on the scholarship of John Dearborn, Noah Rosenblum, and others, and argues that the idea of reorganization began much earlier—in the 1910s and 1920s. Tarbert’s argument thus complicates the image of the New Deal as a singular “constitutional moment,” and contributes to a robust literature on the development of the American State.

Perhaps Tarbert’s most interesting contribution is his argument that the defeat of the federal anti-lynching bill in 1922 sounded a death knell for the elite reformers. Moderate Republicans had adhered to Booker T. Washington’s accommodation of racism up until World War I. Building on work by Megan Ming Francis, Tarbert shows how those same Republicans joined forces with the NAACP in the postwar period and sought to weaponize congressional power to combat lynching. The introduction and support by Warren Harding of the anti-lynching bill was frightening to white supremacist southern Democrats and conservative western Republicans. They saw the potential threat posed by federal power to Jim Crow. These two coalitions then joined forces to successfully curb the expansion of federal power. It was not until Franklin Roosevelt’s sweeping election in 1932 that the expansion of federal power came back in vogue.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court is largely absent from Tarbert’s account, and the narrative would have benefitted from its inclusion. For example, in Myers v. United States, the Court struck down an 1876 federal statute that placed limits on the president’s power to remove a postmaster. Chief Justice Taft, a prominent member of the “elite reformers,” held that the statute violated the separation of powers. As Andrea Katz and Noah Rosenblum have pointed out, Taft was careful not to condemn the civil service, stating that “[t]he independent power of removal by the President alone, under present condition, works no practical interference with the merit system.” Taft’s opinion in Myers thus fits nicely within Tarbert’s book, and even bolsters his argument.

The book’s lack of engagement with the Supreme Court and legal doctrine is, in many ways, a virtue. Tarbert’s book is an engagement with scholars of American Political Development (“APD”) and historians, not necessarily lawyers. But the lack of engagement is also a missed opportunity given the increasing prominence of the administrative state in the federal courts. As an example, the Court recently held the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau unconstitutional, citing Chief Justice Taft’s opinion in Myers approvingly. Curiously, the Court failed to grapple with Chief Justice Taft’s language about the civil service or other historical evidence of broad congressional power over the state. Justice Neil Gorsuch is also leading a charge to more stringently police delegations of power by Congress to the executive branch; a turn to “Americana Administrative Law.” The history that Tarbert supplies is therefore a powerful critique of Justice Gorsuch’s and others’ positions on the administrative state. The book would have benefited had the Court been integrated into the argument a bit more. Of course, this critique is tantamount to asking Tarbert to write a much longer book, but the Court’s absence from the narrative might obscure some of the contributions that the book supplies.

Tarbert’s book joins a rich literature on the creation and development of the American state. It will require historians, APD scholars, and lawyers to grapple with the argument. The book also raises many questions: What role does race and racism play in conservatives’ quest to shrink the administrative state in the mid-twentieth century? What is the relationship between racism and constitutional-political developments such as the unitary executive theory and the nondelegation doctrine? These are important questions with answers that are still being developed. Tarbert’s book thus provides a path forward for legal historians, APD scholars, and political historians alike.

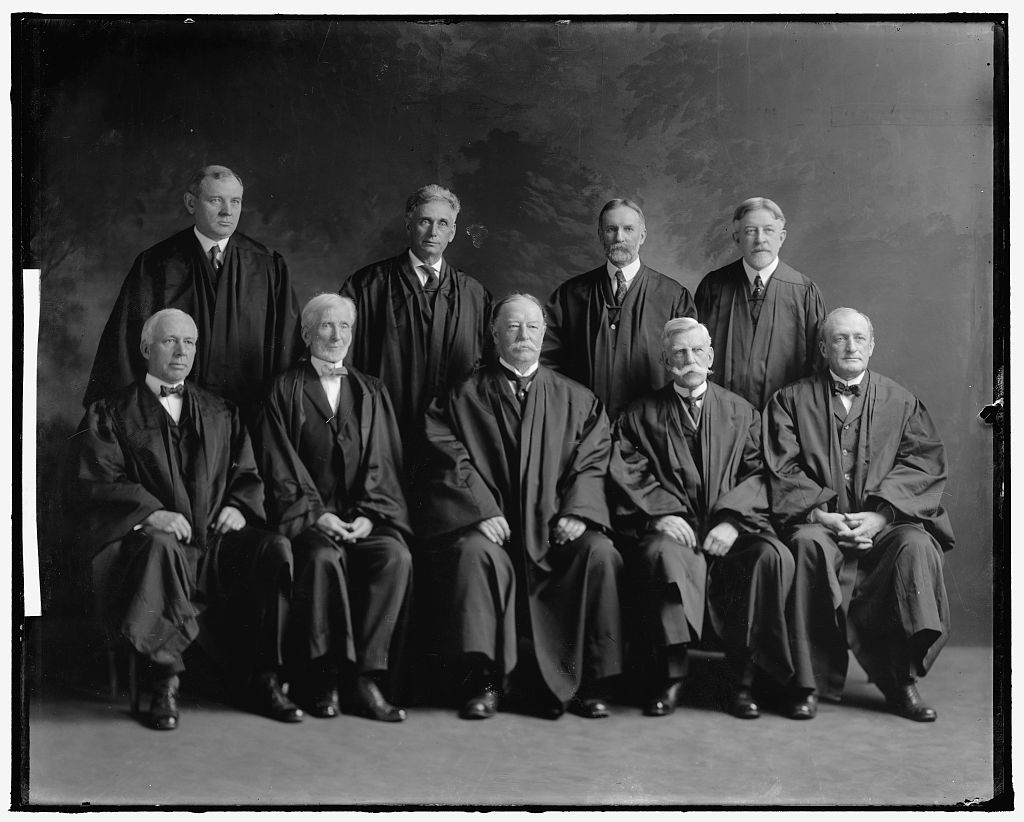

Featured Image is Supreme Court, U.S. Taft Court