Pluralism, Partisanship, and Patriotism

There is no conflict between liberal institutions and liberal partisan politics.

For my entire lifetime, conservatives have smeared liberals as being “anti-American,” “unpatriotic,” and “rootless cosmopolitans.” Dissent and disagreement were treated like disloyalty. Political theorist and “true friend of Liberal Currents” Eric Schliesser is exactly right when he argues that American citizenship does not demand loyalty to our system as it currently exists, to any specific political or moral values, or even to the Constitution—so long as you obey the laws and pay your taxes, you’re free to advocate for abolishing the Constitution and moving to a radically different form of government.

Awkwardly, however, Schliesser’s argument is aimed at me and asks: how can I be a liberal committed to a tolerant, pluralist society and yet call Marc Andreessen and his tech reactionary cohort traitors? What is it that they have betrayed, exactly? What possible coherent formulation of treason could include their conduct?

Let’s take a step back and return to fundamentals. Liberalism is, on the one hand, a range of possible institutional arrangements aimed at protecting the rights and overall freedom of the individuals who live in a country. To be committed to these institutions is precisely to be against the kind of thick, small-r republicanism or jingoistic nationalism that Schliesser criticizes. A liberal conception of citizenship in this sense is minimal and, critically, not at odds with social difference of all kinds. Liberal institutions make room for the reality of pluralism within the rule of law.

It would certainly be illiberal to enshrine in the law that one must be committed to liberal causes or risk being charged with treason. Despite what you might hear coming out of the Manhattan Institute these days, no liberal worthy of the name advocates the death penalty for having insufficient commitment to trans rights or the public funding of science.

On the other hand, liberalism is also a substantive politics pursued by people within the confines of whatever political and legal institutions in which they happen to find themselves. Improving the liberal quality of our institutions in the first sense is almost always a focus of this kind of politics, of course. But it is hardly the only focus, and in a consolidated liberal democracy, it often is not the main focus.

Liberalism cannot simply be a procedural set of mechanisms for adjudicating disputes among illiberal groups. Liberalism needs liberals as a political force. Seeking to preserve and refine the liberal character of the institutions is certainly the bare minimum of what such liberals must do in order to be considered liberals at all. But invariably, they also push for a thicker liberal conception of society—one that actually values enabling people to make their own choices and invests in giving them the tools to do so. One that takes seriously the trade-offs between regulating the externalities produced by private actions and protecting individuals from the power of the state itself.

In the modern world in general and liberal democracies in particular, all politics—conservative, liberal, socialist, fascist—are mediated through party politics. And a healthy party politics entails, in Nancy Rosenblum’s words, “telling a comprehensive public story about the economic, social, and moral changes of the time and about national security.” (Rosenblum, 358) The liberal party, or the party with the largest liberal faction within it, must offer a compelling national vision of the public good. In practice, this always means telling their version of what it means to be a good patriot, a citizen seeking to advance the true good of their home country.

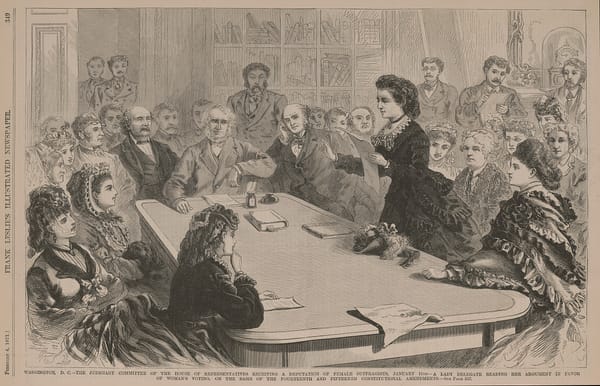

America, like all countries, has a history that cannot be reduced to the good or the bad, but contains a great deal of both. A liberal partisan politics ought to articulate what the best version of America is and can be. We’re a country that has a proud tradition of representative government, however flawed and partial. A country of abolitionists and Reconstruction Republicans, a country that integrates immigrants on an enormous scale and fights for our civil rights. What is striking about our particular moment now is that, even by traditional conservative visions of patriotism, the project of the current administration and its advocates constitute a betrayal.

Visions can be betrayed. That does not mean they fit the legal definition of treason. Marc Andreessen should not be put on trial for supporting Donald Trump, but his actions do suggest the need for exactly the kind of muscular anti-oligarchic politics that Schliesser rightly observes we should have had all along. We allowed markets to produce a class of politically connected billionaires, and defenders of this outcome foolishly argued that it would be to everyone’s benefit. Now that enough billionaires have lined up behind fascism and authoritarian consolidation, it’s clear that liberal governments today and in the future will need to figure out ways to greatly reduce the wealth and social power of that class overall.

I consider it simply part of the practical work of making a case for anti-oligarchic politics to cast Andreessen as a traitor to the liberal democratic ideals of the country he grew up in, the communities he participated in, and the institutions he benefited from. I think “traitor” is the proper moral term for what he is, and “betrayal” is the proper term for what he has done. This is a matter of morality, relative to one vision of what our country ought to be, which of course one is free to agree with or not.

Casting the other side as having betrayed the good of the country is a field of partisan politics one can either participate in or cede to the other side. I understand all too well Schliesser’s argument that “in fighting dirt with dirt, we should be alert to the fact that we do not end up promoting the wrong sort of values.” When fighting authoritarians we must walk a dangerous tightrope to avoid being too passive on the one hand, and adopting too many of the methods of our enemy on the other. But compared to bog-standard political rhetoric that denounces anti-war protesters as traitors, I confess I cannot find it in myself to lose even a minute of sleep turning that label around on fascists.

Bibliography

Rosenblum, Nancy L. On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship. Princeton University Press.

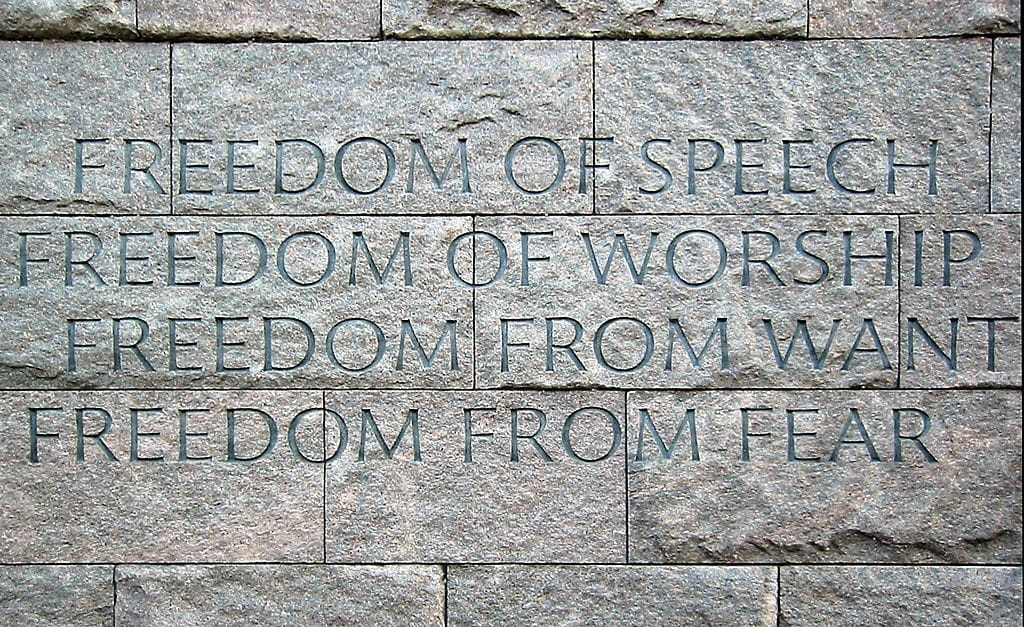

Featured image is Photo of a wall with the "Fouren Freedoms" at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington DC