Politics is a Story

What is necessary more than ever before is a genuinely positive story that liberals can tell the public.

Alan Ryan, in the introduction to his classic On Politics, wrote that if we accept that in all societies only a small number will govern, then it becomes crucial to understand how they secure and retain the allegiance of the many. This is the crisis that many political parties and actors face today. In our data-driven and information-led world, appeals to facts and logic have often led the way for progressive parties. This is predicated upon the assumption that winning the intellectual argument translates into electoral victory.

Yet we live in an era in which political decisions by the electorate are often made without regard to facts or logic. Some commentators, such as James Marriott, fear that the evolution of politics in a world without a strong attachment to literacy and knowledge creates the conditions for the arrival of authoritarianism. However, this condition is hardly new. As Alexander Guerrero argues in Lottocracy, people’s understanding of government and policy has been weak since the 1950s and continues to be so. There has never been a golden age of democracy in which voters were well-versed in policy and voted based on facts. Instead, it has always been a battle between competing stories.

Richard Nixon is perhaps the perfect embodiment of this. Growing up poor in California, Nixon felt shunned, neglected, and second-rate—to the point that, on the night of his second election victory as President, he sat in his office and wrote down a list of criticisms the opposition might say about him. The story of Nixon’s life allows us to better understand why he was involved in Watergate, a completely needless criminal enterprise against an opponent, George McGovern, who never had any real chance of removing him from the White House. If we were merely to piece together the facts, we would only ever find out half the truth; we need the story to make sense of it all.

The same is true for voters. Not only do the majority of voters not understand the government, its processes, or the factual state of the economy and the world around us, but such understanding, even if present, should not be sufficient to choose a party, even if it were the case. Facts alone are a fundamentally unreasonable basis on which to vote. If voters do not understand the facts of government, then how else are they making decisions about who should govern? Here we arrive at values. As Carl Schmitt argued in Constitutional Theory, a constitution is insufficient without direct legitimation from the people expressing their will. Just as this is true of a constitution, so it is true of a political party. Formalism and data are not reasonable methods for discerning the true will of a people; instead, they must be told a story of who and what they are.

Recognising this statement as the premise of politics is perhaps a little old-fashioned—dare I say it in Liberal Currents—maybe even a little conservative. In a world dominated by data and statistics, appealing to the logic of the mind alone is believed to be a risky affair. Governments and parties need only produce graphs showing the increase or decrease in GDP, migrant numbers, and happiness surveys, and success is assured. Built into this claim is the assumption that politics, as a matter of values, has largely been settled. Now, it's simply a matter of implementing the policy.

Yet such a modern approach to government and politics is de-rooted from experience. It was an approach fit for the 1990s and early 2000s, an era when social democrats reigned supreme and even Conservatives had to mould themselves to their agenda in the vain hope of being elected. But it is no longer that era. Today, we live in an age of vicious contestation, one that data and an appeal to facts cannot lead us out of. Instead, political parties, especially those on the progressive side of politics, must go further and tell us a story about society.

As Leo Strauss argues in Natural Right and History, politics is a quest for wisdom that can never be fully attained. This is because, unlike facts, values can never be fully reconciled with reality or decided upon objectively. This is not to reject values as a method of politics, or to say some values have a stronger reasoning behind them than others, but to recognise that, when asserting values, we cannot be neutral or objective—we always end up speculating about which ones are stronger. Facts alone are insufficient to build a compelling message; we need something much more.

As Aristotle says in The Politics, every state is a community established to create some form of good. Justice, according to this account, is the principle ordering of any political society. Even though Aristotle believed that justice constituted an account of politics that provided an advantage to the state and the common good for its citizens, this description, when read today, necessarily raises the question of what precisely constitutes advantage for those citizens.

That battle is the crucial one that governments and political parties need to take up. It is not sufficient to point to a graph and declare that we are becoming richer. As Hannah Arendt highlights in The Human Condition, man is a social animal even when we exist in largely isolated environments. Experientially, finding the right words at the right time to construct a narrative is just as powerful, if not more powerful, than a million graphs demonstrating policy success. Having given up violence as the primary method of resolving conflict internally, politics became a matter of persuasion, and such persuasion is not rooted in numbers but in imagination.

Recognising the role of significant differences in values and asserting your own values is necessary in politics. But in doing so, political actors must recognise that their ideas are not akin to facts or logic. If actors make such a mistake, they risk asserting that their story is the only possible one. That cannot be conducive to democratic or liberal politics, which requires diversity of thought to exist unimpeded in order to flourish.

Our desire to establish an objective, rational, scientific, or common-sense basis for our ideas misuses values in service of a fact. Jason Blakely’s Lost in Ideology highlights how such an approach has not led to a post-ideological age, but one in which ideology is reflected back at us, making our beliefs appear natural and fact-oriented. In this world, we often become lost in our own ideologies, unable to understand or contemplate those of our opponents. This is how we end up shouting on the TV against our ideological opponents.

However, this is not a new phenomenon, nor is it confined only to conservative causes. John Stuart Mill labelled conservatives “the stupid party,” and On Liberty, although a very great text, has moments where dismissal and assumption are apparent in Mill’s thinking. We can also witness this in Utilitarianism, where Mill supposes it is better to be unhappy in the search for meaning than to vegetate in pleasure. The failure of Mill here is not that he demands more of us than we often want to give; rather, he asserts that this must be the correct way and seemingly cannot comprehend another system being as reasonable.

This is the same mistake conservatives make when they proclaim their worldview as merely one of experience. Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind argues that conservatism is not a body of dogma but rather a philosophy that adapts to the times. My old British politics lecturer used to label conservatism as a system “devoid of change,” a charge that would surely raise Kirk’s ire if he were around today. However, asserting conservatism as the idea of ‘common sense’ overlooks the underlying ideology and narrative that conservatism has to tell. It positions conservatism as the natural system of being.

When telling our stories, we need to ensure we do not become so wrapped up in them that we forget they are what we make them. Stories are not universally bought and cannot be imposed on others at the point of a gun or by other forms of force. John Locke was not wrong when he argued that force can only grant you submission, not belief. We may even think that story cannot fully eradicate reality, even if it can shift the pendulum quite significantly.

Jonn Elledge, when writing about the power of imagination through the lens of Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities,” fails to convey this point strongly enough. Anderson’s belief in the power of story, merged with technology, focuses on nation-building during the time of empire. The lineage of this has trickled down to suggest that all politics can fit into this template. However, Anderson’s account fails to address modern concerns over significant heterogeneity in the polity, namely, contestations over stories and boundaries that defy his specific modelling. Stories of the nation and politics rarely stand as still as Anderson suggests—instead, they need to keep pace with the world around us.

Stories, not facts, therefore remain important when navigating electoral terrain. But it is more complex than this. We cannot become so engulfed in our own stories that we replace the space for facts with them. Functionally, they should operate on different planes. We can never forget the importance of persuasion in politics—ramming our story down other people’s throats until they choke does not persuade them of anything. It merely reminds them of your own belief and determination so that they can hear and buy into your story. The power of story has to be managed carefully.

Current state of UK politics

This leads to the question of how progressive political forces in the UK are using and responding to the story. Labour came into power on the back of fifteen years of Conservative rule, which started poorly and only worsened. By the time Starmer entered No. 10 in a landslide Parliamentary but shaky electoral majority, the state was in disarray.

Starmer spent almost the entire campaign reminding Britons of two things. First, that he did not come from a privileged background, and second, that it would take time to fix the messes he had inherited. From the NHS to Transport, to higher education, to multiple councils declaring bankruptcy, he was right to emphasise that there would be no miracle cure. It was grim news but honest, and deep in their hearts a lot of us knew he was right. As hilarious as we all found Liz Truss’s inability to outlast a cabbage as prime minister, the damage wrought on the country’s finances was significant, and the truth is that we are still paying the price.

The election campaign messaging, which ran on the notion that things could only get better slowly, wasn’t wrong. It spoke to the deep failure of the Conservative Party, which had prioritised internal fights over the well-being of everyone else. But, as the saying goes, you campaign in poetry and govern in prose. If this were a novel, it would not be a Booker winner but would be in the bargain basket at your local charity shop.

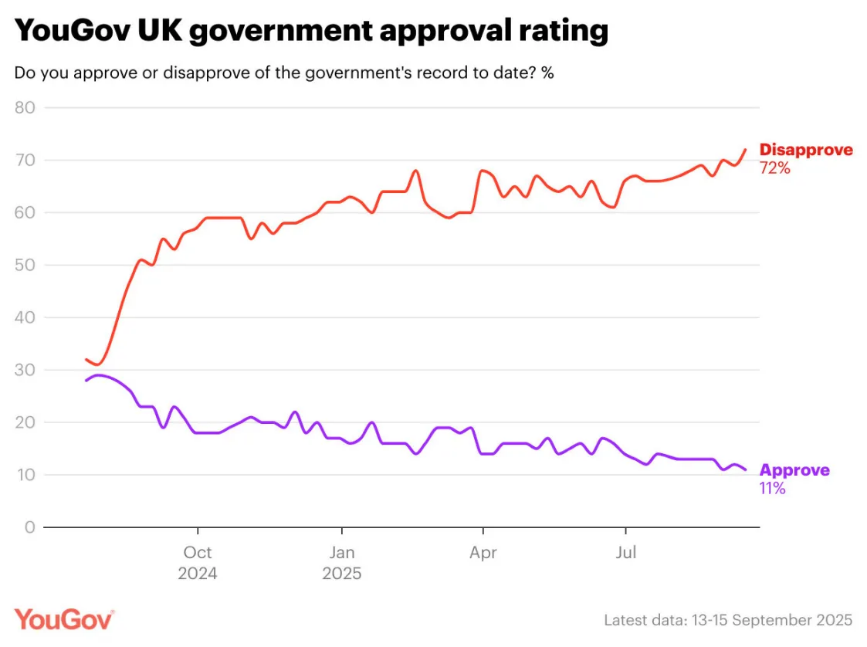

The result is political anger all around. No political party or leader is particularly popular. Ed Davey, the Liberal Democrat leader, has the strongest approval rating at -6. In contrast, Keir Starmer, the Labour prime minister, suffers from a -50 approval rating and is a distant second behind the far-right Reform UK, which still cannot poll above 30% of the electorate. In essence, the UK electorate currently dislikes everyone and is unleashing its wrath on the established political parties that have dominated British politics for more than a century.

There are plenty of policy proposals that Labour is being told to prioritise in a desperate bid to turn the electoral tide. These range from controlling inflation to cutting red tape around house building to cultivate a coalition that can keep Labour in No. 10 after the next General Election. The truth is, Labour has plenty of time. The general election was only a year ago, and Labour has time to produce an economic turnaround that could keep them in power. However, policies alone will not be enough to save a government that is suffering from a disapproval rating no one thought possible even twelve months ago.

The lack of a narrative from Keir Starmer and Labour has been devastating on a wide range of fronts. It has allowed anti-immigrant sentiment to creep up and even partly devour the prime minister, who delivered a poorly timed and ill-conceived “islands of strangers” speech that he later apologised for, blaming his fragile state of mind following an arson attack at his family home shortly before giving it. Regardless of the circumstances, the fact that such a speech could have crossed his desk speaks volumes about the lack of direction and story not only within Starmer himself but also within his wider team.

Combined with scandals over designating Palestine Action a terrorist group and clampdowns on trans rights via the Supreme Court ruling, Labour has been running out of allies across the political spectrum. Presenting themselves as “non-ideological,” taking from both the right, left, and center on social and economic policy, they have generated frustration from both the left and right. The result is displeasing to everyone: a confused hodgepodge of a program that fails to hit the mark despite real wins. In an economy that is the fastest-growing in the G7 and creating real-terms wage growth, along with the long-awaited nationalisation of the rail service, people should be feeling happy with the slow but correct direction in which the country is going.

“It’s hopeless,” one minister said. “Too many people feel the country is in decline and the only route back is big, radical solutions. We’re doing lots of good stuff but it barely gets noticed. It just doesn’t hit the mark.”

Instead, the vacuum is exposed by this government’s lack of a story. The result is a weird focus on paedophile politics, the small boats crossing the Channel, and racist marches that exist at the tipping point of an increasingly poisonous politics. We can no longer pretend it isn’t happening—the soft English side of caution is starting to develop a much harder edge as both major political parties watch the radical right goad them into a response. The march on London, attracting around 100,000 people, should be a stark warning about what could happen if both Labour and Conservatives don’t get their acts together as of right now.

Nigel Farage, the leader of Reform, can turn Labour’s inability to define itself into a revolutionary attack on the duopoly of British politics, albeit an attack filled with loons, incompetents, sycophants, and racists. Reform is no different from UKIP, a carnival led by a charlatan who will skirt right up to the edge of the far right with a wink and a nod. Farage, much like Johnson, is well adapted to summon up that “British charisma” with a quick joke while smoking or drinking a pint of beer. As performative as it is, it seemingly does work, as does forever sniping from the sidelines without having to think of too much of an alternative apart from “Modern Britain is shit.”

We have seen this before. All the way back in 2016, the Remain campaign surely couldn’t lose the Brexit referendum. In the UK, Brexit succeeded despite a lack of coherence in the campaign strategy, and the leaders of both the Conservative and Labour Parties backed the Remain campaign. However, Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour Party, presented himself as an ambivalent figure throughout the campaign. What the Brexit campaign was able to do was weave together popular frustrations over political elites, immigration, and a sluggish economy to paint a picture of European dominance putting a leash on the British bulldog.

The Remain campaign’s Project Fear was not only riven by internal factionalism but also failed to provide a story as to why the UK should want to remain in the European Union. Instead, the Remain campaign and its post-referendum child focused too much on their opposition rather than on a positive vision of a Britain in Europe. The wider strategic necessity of belonging with the UK’s partners in Europe was almost completely neglected as Project Fear kicked in and focused on the death spiral of the UK’s economy if we left.

Labour, just like the Remain campaign, cannot merely point to the awfulness of its opposition. Although there is a strong case that Starmer needs to loosen the leash and go on the attack against Reform. What is necessary more than ever before is a genuinely positive story that Labour can tell the public. It is already there, waiting for them in the fine print; they simply have to be bold enough to tell it.

Featured image is Emma Zorn reading, by Anders Zorn