Reviewer Judge Words in Book: Bronze Age Mindset, Reviewed

We can be more and better than conquerors and thieves.

Bronze Age Mindset is distracting book. Distracting is on purpose. Poorly written on purpose too. Editor say no? Writer say fuck you, I write. Book like that.

Of course, there was no editor. We know this because its literary devices fail—the literary device called the paragraph break is never attempted—the history is almost entirely garbage, and the metaphysics is even worse.

Bronze Age Mindset may also be the most important book in America right now. And it’ll stay important for at least as long as our current Leader draws breath. Our Leader’s followers love this book.

Book maybe important in far future too. Author sure hope so.

But the caveman talk strewn irregularly throughout doesn’t help, and an editor might have said so. An editor might have added that the British did not establish the American colonies because early 17th-century Britain was already industrialized and enjoying a low infant mortality rate. I’m not sure that an editor could help with the author’s conviction that a mystical force pervades the universe and works in favor of fascism, but I might have said a word or two in the rejection note.

For good or bad, a self-published book that succeeds at the highest levels will tend to attract attention and stick in the mind. Future historians, if there are any, will unfortunately look to this book to try to understand you and me. They’ll ask this book what passed for wisdom among us. It’s that kind of book, I’m sorry to say, and that’s why I’m writing.

People say is racist book. Not wrong. They say is fascist book. Not wrong also.

They’ll say that the book is illiterate, but that’s where they’ll stumble. It’s not illiterate. It’s anti-literate. It’s a call to dismantle the world that things like mass literacy made possible. It’s an attempt to bring back certain things from the time before there was much literacy, even among the upper classes.

The author hopes his readers will sweep away the reigning orthodoxy—literate, peaceable, feminized, and specialized: “You must show them for what they are, which is, dour, old, sclerotic, ugly, pedantic” (74). The present day represents “a return of the endless sallow night of matriarchy” (48).

Like complain about grammar or spelling. Huemans do that, is bad huemans. Hue-mans. (Get it?) Bugmen.

Higher man use words how he want. Higher man conquer! Grammar for bugmen.

That’s what this book is about, really. It recommends conquest. It laments the monopolization of conquest by professional militaries who, in our late and fallen days, only serve to prop up a supposedly reigning gynocracy. If conquest were more accessible to young white men, then the best of us would be happier.

And that’s what society should be all about—our specialest boys, and no one else. Young, conquering men should be worshipped; they’re the force that the universe itself demands, and the universe wields them whenever great deeds are afoot.

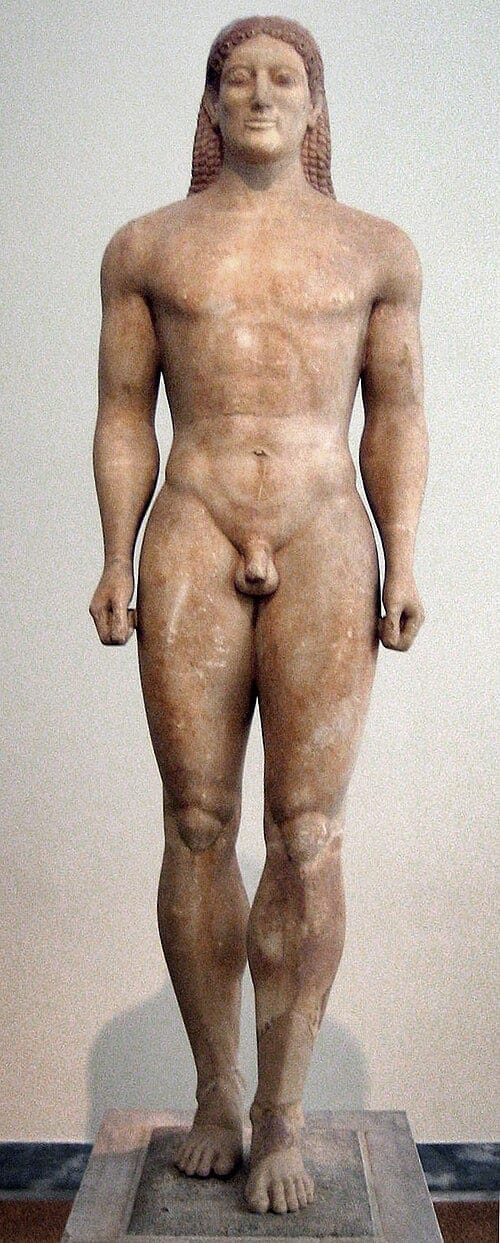

Uncomfortably, the author practices what he preaches. He relates how he once got an accomplice to let him into a museum alone (59). There, for three hours, he contemplated an ancient Greek kouros sculpture until, without touching himself, he experienced an orgasm—a feat of eroticism that this reviewer has never equaled in all his years as a practicing homosexual.

As little as a decade ago, conservatives would have called this episode both criminal and tawdry; on this, they’d not have been wrong. They’d also have seen it as proof that homosexuals shouldn’t be trusted with anything. (I’d say: Well, not that one.)

All that aside, standalone kouros-worship isn’t a religion that points to civilizational stability, and the author knows it. He’s not looking for civilizational stability. He’s hoping to unmoor western masculine energy from its current, somewhat disaffected place in society, and turn it toward sweeping away the entire decadent modern world: “In the next hundred years and even before, barbaric piratical brotherhoods will wipe away this corrupt civilization as they did at the end of the Bronze Age” (76).

We’re told that the Bronze Age valorized the kouros because it valorized the power of militarily gifted young men exploring the world and taking whatever they desired. This is also the project of the author, the self-styled Bronze Age Pervert. The kouros may have been sacred to Apollo, but the urge he feels is Dionysian: He’s not hoping for a finely balanced Republic, nor for an idealized, well-functioning Bronze Age, as depicted on the shield of Achilles. No, he’s hoping for a sudden burst of violent destruction followed by… he’s kind of quiet about that. The pirates will win. They’ll destroy modern states and institutions, allegedly for being gynocratic. Then they’ll retreat to “fortresses on the edge of the civilized world,” where they’ll guide humanity from the shadows, offering the nations “defense in exchange for a price.” Most of us will have to fend for ourselves, deprived of all that supposedly makes humanity good (77).

I assure you that I feel weird making a case for ancient Greek patriarchy, but next to this, even ancient Greek patriarchy would be an improvement. It’s all in Plato: Mastery over the animal parts of the soul is a classical Greek virtue; they’d call it a derangement to cultivate the opposite. You, a man, must master the animal parts of your own self in the same way that you master the animal parts of society. The animal parts can take, but not hold; they can lust, but not love.

Classical Greece knew it well. It had weathered both the Bronze Age and the Dark Age that followed. It sought to draw its own young men into a stable social system, from one generation to the next; its myths were often crafted to show young men what was expected. Classical Greek writing about the Bronze Age in particular is almost always an autopsy of a failure, written long after the fact, with what they hoped was a recipe for doing better: Don’t collect women like trophies. Be faithful to one household. Tend to your children. Think of the continuity of your bloodline.

Creepy as we may find the patriarchal bargain, it certainly worked better than the old way. Homer wasn’t writing to glorify the Bronze Age. He lived in the wreckage of the Bronze Age. Every day his shattered society reminded him of that age’s failures—once strong, it had collapsed across such a wide geographic region that whole empires and systems of writing disappeared forever. Homer wanted something built to last, which was only reasonable.

As I’ve written elsewhere, Homer didn’t want the future to look like Achilles and Agamemnon fighting over slave girls forever. He wanted it to look like Odysseus being tied to the mast, returning to Penelope, and managing his household in peace and fatherly cleverness. The Bronze Age was for boys—that’s Homer’s moral in a monosyllabic sentence. (Was Odysseus faithful? Shh! Don’t wreck the bargain.)

I also think of Ovid’s Pygmalion: Here was a fool who sculpted a woman because he hated actual women. Our author, the enemy of actual men, likewise prefers a statue. When Venus brought Pygmalion’s statue to life, it was for revenge, and the moral was to teach him to grow up already: Now you must meet the unknown and the uncontrolled, in the form of a living, breathing woman; now you must face the messiness and mortality of loving someone with a human life, real but finite. You must love someone who will menstruate, fart, feel attractions to other people, and eventually die: You get what you get in life, and here it is.

If she’d had a speaking part, Venus might have said, “It’s desire, sculptor, that brought you here, to the dirty, humdrum, feminized home. Being a good man means you look frailty in the eye, and you love and care for people anyway.”

To Pygmalion’s credit, he married his art—and behold, the goddess worked a still greater transformation: a sick, isolated mind, afraid of womanly desires and bodies, nonetheless grew into the patriarch of a family, the grandfather of Adonis, a god in his own right. American conservatives also used to say that marriage to a woman domesticates a man, and that’s part of why marriage matters.

Mistrusting family, though, is another common thread of Bronze Age Mindset. “By all means, marry and have children if you want, but don’t do it as a political statement or a form of action,” he writes. “The idea that whites or Japanese should start vomiting out six or seven children to a vagina like the illiterate slave hordes of Bangladesh or Niger is absurd… Usually a family is the end of a man” (75).

You’ll do better if you stick close to your brothers in arms, and the men the author praises generally achieve what they do without the burden of a family or children. If they have either, they’re a small part of their story as Bronze Age Pervert tells it. Rather he hopes that his young, unmarried readers will start a career in the military, a paramilitary group, or—I assure you the author isn’t kidding—as a pirate.

Of the conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, Bronze Age Pervert writes: “once conquests were made, he never stopped. His thirst for space, for new worlds, for new conquests, was without end… This man was a born pirate… Alvarado was a nemesis to civilization, and this is right and good… I want you to be like this” (61). By sheer coincidence, I’m sure, Alvarado happens to have been a prodigious killer of Native Americans, and a scandal even to other conquistadors.

Or consider Bob Denard (62). Denard was a twentieth-century blue-eyed African warlord, French by birth, a white supremacist, who seemingly never met a coup attempt he didn’t like. We learn that he “shows that the spirit of Bronze Age pirate can exist also in our age. It can flower complete and unedited. You have no excuse! … In many ways he defended whatever residues of civilization remained in Africa after decolonization.” He also converted to both Judaism and Islam, though I sense that talking about it would complicate the story in view, in ways the author wouldn’t care to explore.

As a general rule, whenever Bronze Age Mindset drops a name or an event without much context, you’ll make a good guess if you say that it’s Nazi or white supremacist. Who’s Erik Jan Hanussen? One of Hitler’s kooky charlatan advisors. Who’s “Nehlen”? White supremacist, lost to Paul Ryan. What are “green gloves in Hong Kong”? That’s about that one time when some Nazis got into Buddhist mysticism. And on and on. “They live in the realm of power and freedom” (41), says the author. Who doesn’t like power and freedom?

All of this is so, so tiresome. The retreat of human physical force from economic activity, and the advance of mass literacy, let women be productive and contribute to society in ways that weren’t so accessible to them before. Of course they would ask for a greater share in politics; of course such a share should be given, and it was. We aren’t pirates anymore. We live in a civilization. We can be more and better than that.

Many of our seemingly solid intuitive judgments, the kind the author puts so much weight on—the ones we might want to call instinctive—have fallen to modernity’s quantification and falsification. This shows clearest in the book’s early sections, where the author makes a muddle of trying to refute and replace Darwinian natural selection, preferably with something more authoritarian. Those who can count know better: the nationalistic stories we’ve told ourselves about bloodlines are both false and recent, and we should mistrust them. Nothing peculiar to your white ancestry makes you any more a child of the universe than anyone else. The modern world has put a lot of this spiritualist mythmaking to bed. We’ve developed new social practices that are informed by quantitative research, not gut feelings about skin colors, and we’re healthier and richer as a result.

When economics got quantified, we gained even more: Shopkeepers could understand, now, that their place in the world was not without use or honor. We can say now, with our greater understanding, that finding what’s needed and delivering it at an honest, competitive price is exactly how the world improves. But unlike both manufacturing and retail, conquest never makes any new wealth at all. Conquest only moves the wealth around, and some of it always gets ruined in the process. Conquest may feel good, but its partisans are both cheats, without good title to their claims, and wreckers, who squander the world’s stock of resources.

As even Homer knew, such men don’t make a stable society. The best they can do is to play cruel games on the margins of the governed world. Without that governed world to fund them, they could only dream of being soldiers. That’s what I predict for this book’s real-world acolytes: I foresee a lot of frustrated, tragicomic military careers. I predict spree killings, self-important social media trolls, and a few latent homosexuals with more money than prudence conducting lunatic foreign adventures. If people like these retreat to the margins, they won’t be missed. They might do best to find a living, breathing man and make love to him, but I already suspect that they can’t handle it.

Featured image is "Closeup of Achilles thniskon in Corfu Achilleion autocorrected," CC BY-SA 3.0 Dr. K.