Speech That Plays It Safe Does Not Remain Free for Long

Fierce disputation and colorful variety are often a sign of a society in good health, not terminal decline.

Shortly after video footage of the death of Renee Good was released online, Daily Wire commentator Matt Walsh wrote in amazement that ‘‘This lesbian agitator gave her life to protect 68 IQ Somali scammers who couldn't give less of a sh*t about her.’’ Walsh had previously asserted that ‘‘the average IQ in Somalia is 68, which is below the line for mental retardation.’’ His comments were crafted to remind the world, including those who might respond negatively to videos of an unarmed civilian getting shot in the face, that Somali people are too contemptible to be worth defending, never mind dying for. A similar verdict has been pronounced over the death of Alex Pettri, the nurse who was shot dead by ICE agents in Minneapolis. Defenders of the regime describe his death as a reckless waste of life: had he stayed home and not brought a gun to an anti-government protest, they argue, he would still be alive today. ‘‘I know I’m supposed to feel sorry for Alex Pretti but I don’t,’’ confessed Megyn Kelly, host of the Megyn Kelly Show. ‘‘You know why I wasn’t shot by Border Patrol this weekend? Because I kept my ass inside and out of their operations. It’s very simple. If I felt strongly enough about something the government was doing that I would go out and protest, I would do it peacefully on the sidewalk without interfering via a whistle, via shouting, via my body, via any other way; I would make my objection known by standing there without interfering.’’

This call to ‘stay home and stay safe’ may be sensible in certain very specific contexts, but if universally adopted may weaken the power and effectiveness of freedom of speech. Such a wholesale refusal to engage with the activities of one’s government represents a dangerous acquiescence to state power. In Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949), the majority opinion, led by Justice William O. Douglas, affirmed the idea that ‘‘a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute.’’ Free speech, the court explained, ‘‘may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.’’ There is nothing about this view of free speech that suggests that a quiet and passive discussion of ideas in the safety of one’s home or on the quiet sidelines of society is the ideal mode of expression in a democratic society. On the contrary, tense, heated, and socially disruptive speech such as the ones which broke out in Minneapolis can on occasion be more conducive to moral and political breakthroughs than regular parliamentary proceedings.

Whether one thinks protesting in the streets of Minneapolis is a wise action or not, it remains the case that Americans have a right to vigorously protest the actions of the state, and not fear being killed for it. In fact, it was Justice Douglas’s opinion that ‘‘the right to speak freely and to promote diversity of ideas and programs,’’ is ‘‘one of the chief distinctions that sets us apart from totalitarian regimes.’’ To believe, whether implicitly or explicitly, that public protests are only justified when complainants protest quietly, or when the government deems the protests appropriate, or when the victims are lionized by the administration and its backers, is to give far too much credit to the state. What is most worrying about this attitude is that it is in fact exactly the kind of uncritical obeisance that the President of the United States has come to expect of the American people: ‘‘I value loyalty above everything else—more than brains, more than drive and more than energy,’’ Trump said.

Disloyalty, either to the President or his agenda, is not just frowned upon, but strongly punished.The President and his most unbending supporters have never been shy about their desire to mute any criticism of the MAGA agenda and impose, by force if necessary, a sense of quietude in America. When asked what he would do to crush the ‘radical revolution’ on university campuses, President Trump replied that his first act would be to threaten the troublesome students with deportation. ‘‘As soon as they hear that,’’ Trump emphasized, ‘‘they’re going to behave.’’ It is not surprising, therefore, that when confronted with public furor over his immigration policies, President Trump’s first instinct was to threaten to invoke the Insurrection Act and deploy military troops to quiet the protests in Minneapolis.

As historians, political scientists, and concerned legislators have noted, Trump’s willingness to use the intimidating power of the state to silence his critics is very much ‘‘the standard format for every budding despot.’’ In authoritarian societies, the spectacle of public punishment is deployed by the state to suppress those energies which the German philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt regarded as ‘‘the source of every active virtue’’ and the basis upon which ‘‘the whole greatness of mankind ultimately depends.’’ (The Limits of State Action, pp.7,12)

Born in Potsdam (Germany) in 1767, Humboldt lived and moved in a cloistered society of eager conformists, sternly held in place by the notoriously bureaucratic state of Prussia. Seeing complete freedom of thought as too risky a concession to the public, King Frederick The Great and his successors sought to maintain the state’s formidable grip on public opinion. As Edmund Fawcett notes in his history of liberalism, ‘‘prior censorship, where it existed, was spotty and haphazard, but the threat of reprisal was enough to make people think twice before speaking their minds. Punishments were frequently cruel and spectacular, especially if you were poor, defied power, or flouted orthodox opinion.’’ (Liberalism, p.34)

Humboldt, like most prudent eighteenth-century Europeans, kept his opinions to himself, and withheld the publication of his most provocative political tracts until after his death. His metaphysics alone would have probably attracted censure. Humboldt conceived of society as a dynamic eco-system in which natural spontaneity and vitality are ever present signs of life. Humboldt’s liberal cosmology elevated conflict and friction as integral parts of structured reality; as evidence of a flourishing society.

In accordance with this understanding of natural order, Humboldt saw furious ingenuity, innovation, and creativity as evidence of a healthy society. Energy, he believed, was the motor of human life; without it, ‘‘nothing good or great can flourish.’’ In his writings, Humboldt described energy as the ‘‘original source of all spontaneous activity,’’ and the essential quality that makes human beings ‘‘ingenious in the invention of schemes’’ and ‘‘courageous in their execution.’’ Wherever there is wondrous art, scientific breakthroughs, and political upheaval, there must be self-motivating passion and intelligent organization, for every ‘‘manifestation of energy presupposes the existence of enthusiasm.’’ (The Limits, pp. 18-19)

Taking stock of all the good things that are produced by the struggle, strife, and obsessive drive of humanity, Humboldt confessed that, ‘‘energy appears to me to be first and unique virtue of mankind.’’ The meaning of this expression comes more clearly into view when one considers the sphere of ethics. To determine that a wrong is being committed, and to articulate this wrong to other citizens in hopes of bringing about a change in public sentiment and policy, requires not only courage, but tenacity and a fervent dedication to justice.

The problem is that in a censorious society, people’s desires for magnificence (from the Latin magni, meaning great and ficere, meaning to do = to do great deeds) are commonly frustrated by the designs of repressive authorities. People are not allowed to advocate for the cause of justice, to courageously argue or protest, or to experience the full range of moral development that takes place when one actively engages one’s community. Instead of an impassioned plea for change, quiet indignation takes the place of boisterous public speech, and an already existing tendency toward uniformity of opinion is aggravated by what von Humboldt saw as ‘‘the evil of diminished energy.’’ (The Limits, p.8)

Depending on ‘‘the spirit which prevails in its government’’ an excessive interference with the thoughts and actions of citizens will tend not only to ‘‘fetter the free play of individual energies,’’ but to produce like-mindedness (The Limits, p.18) In ‘‘proportion as State interference increases,’’ Humboldt explained, ‘‘the agents to which it is applied come to resemble each other.’’ (The Limits, p.18) It was Humboldt’s studied opinion that this likeness of mind and opinion was ‘‘the very design which States have in view.’’ (The Limits, p.18) This state-orchestrated drive for uniformity was part of a larger drive for serenity. States, Humboldt averred, ‘‘desire comfort, ease, tranquility,’’ and these ‘‘are most readily secured to the extent that there is no clash of individualities.’’ (The Limits, p.18)

Humboldt’s primal fear was that recurring interference with the spontaneous order of nature could risk upsetting the ecological balance of society, and with it, the happiness of mankind. When the state ‘‘fetters individual spontaneity by too detailed interference,’’ he warned, the beautiful aspects of human existence are needlessly stifled (The Limits, p.21) Men and women no longer initiate much-needed moral crusades, grand architectural projects, new scientific inquiries, or curious art. Instead, they content themselves with their lot in life and disappear into self-imposed obscurity.

This ‘‘suppression of all active energy’’ results in ‘‘the deterioration of the moral character’’ of citizens as regulated people increasingly look away, keep their heads down, and restrict their moral outrage to the secure confines of their home and the impenetrability of their conscience.

‘‘Coercion and guidance’’ Humboldt asserted, ‘‘can never succeed in producing virtue.’’ If anything, he added, ‘‘they manifestly tend to weaken energy.’’ Freedom on the other hand, ‘‘heightens energy, and, as the natural consequence, promotes all kinds of liberality.’’ (The Limits, pp.72, 80)

As such the only true path to individual happiness and social progress is laissez-faire. This expression has been irreparably sullied by the often reckless and remorseless amorality of certain ‘libertarian’ entrepreneurs, but meant something different and fully sensible to people who lived in highly stifling times. To promote laissez-faire, in Humboldt’s understanding of the term, is to allow individuals to express the fullness of their personality, and the full reach of their capacity, for the benefit of mankind. Exhibiting his belief in the felicity-enhancing value of freedom, Humboldt would famously assert that, ‘‘The true end of Man…is the highest and most harmonious development of his powers to a complete and consistent whole. Freedom is the first and indispensable condition which the possibility of such a development presupposes.’’ (The Limits, p.10) Without freedom to protest aggressively, citizens are stunted in their moral and intellectual development, and society needlessly handicapped in its civilizational progress by the bottling of creative energies.

The Trump administration may believe that it is securing the public interest by preventing loud, animated, and provocative protests. It may even believe that by freezing immigration and deporting as many immigrants as possible, it may succeed in arresting the ‘browning’ of the country, but as Humboldt and other liberal-minded philosophers have shown, fierce disputation and colorful variety are often a sign of good health, not terminal decline. It is rather the silence of public censorship and the monotone dullness of an artificial homogenization that announces the death throes of the body politic.

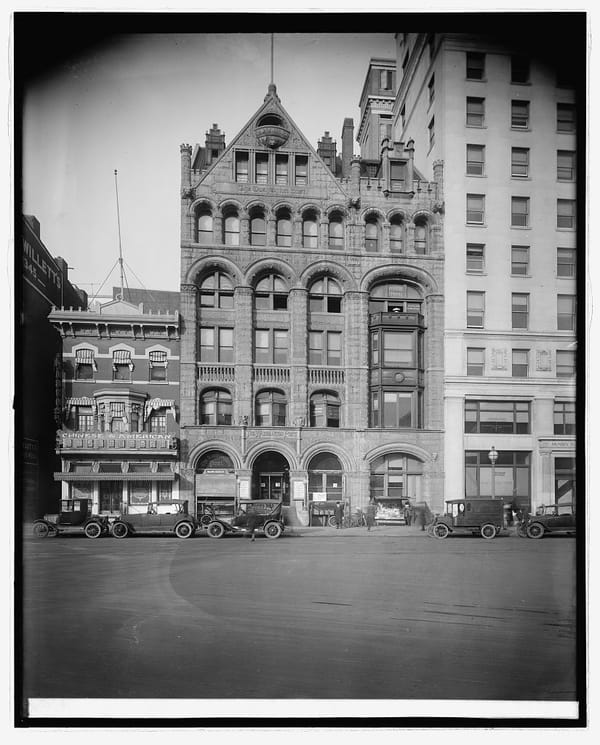

Featured image is Lincoln Steffens