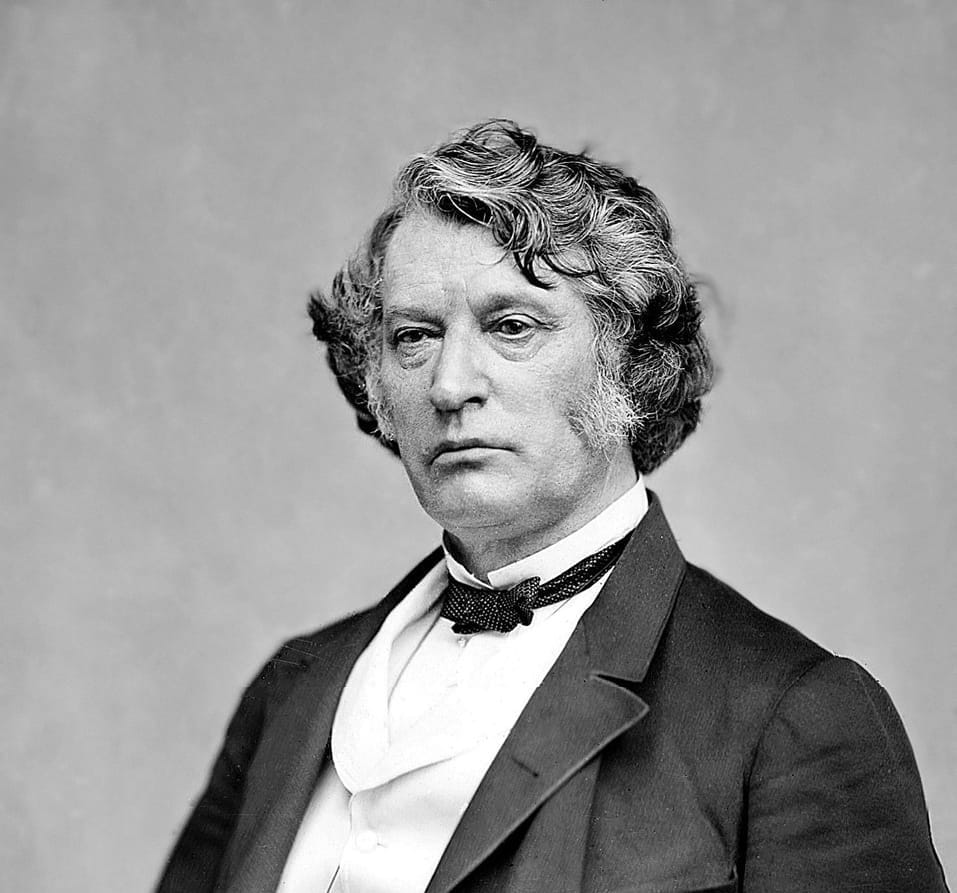

The American Conscience

Charles Sumner’s fight for equality.

In 1785, the colonial residents of Kingston, Jamaica, were warned by local authorities not to bathe in the city harbor. The waters surrounding the main dock were known to contain human remains (something that both town officials and residents tolerated), but on this occasion, the putrefying bodies of African slaves had finally attracted hungry sharks. Accustomed to seeing black life as cheap and disposable, what moved the Kingston health officials to action was not the regular dumping of human bodies in the city harbor, but the fear that some care-free colonial might receive a shark bite.[1]

The routine disposal of human cargo was a predictable response to the high mortality rates aboard traveling slave ships. Recent studies have shown that it was not at all uncommon for slave ships to arrive at their destination carrying the bodies of the deceased, as well as the sickly remains of those on the brink of death. According to one estimate, 4% of the Africans who made it to the Americas died before they could be sold off. To facilitate the sale of the remaining captives, slave captains would secretly hurl the stiff lifeless bodies of bondspeople into the shallow water, then proceed to present the supposedly ‘untainted’ batch to potential buyers.[2]

The transformation of Atlantic slave ports into human dumping grounds was in many ways an unpleasant but necessary consequence of cross-continental human trafficking in the eighteenth century. The harsh conditions at sea meant that only a small fraction of voyages, roughly 4% of them, made it to their destination without suffering a single loss of life.

Over the course of the long eighteenth century (1730–1807), almost half a million African passengers died at sea. The most frantic period of slave trading in America were the years 1804–1807 when slave merchants rushed to import as many slaves into busy ports like Charleston, South Carolina, before the federal ban on the slave trade could take effect. An estimated 65,000 Africans landed in the United States during this four-year period, representing a remarkable 17% of all enslaved Africans ever brought to North America.[3]

So many dead bodies stenched the ports of American cities during this import rush that by 1807—a year before the congressional ban on the slave trade—even the cotton-loving government of Charleston was forced to issue a statement condemning the ‘‘inhuman and brutal custom’’ of throwing dead Africans into South Carolina’s Cooper River to ‘‘save the expense of burial.’’ After at least seven bodies were discovered floating along city waters in April of 1807, councilmen imposed a $100 fine on anyone caught offloading deceased passengers into the sea.[4]

Like the government men of Kingston, Jamaica, the health authorities in Charleston, South Carolina, were not primarily motivated by a desire to secure the welfare of Africans. Their goal was to better regulate the trade to ensure that the slave economy would continue to grow. If anything, short of an outright ban on slavery, legislative efforts to turn the traffic into a more ‘humane’ institution—especially after a political revolution—have historically worked to boost the sale of slaves and further immiserate captive populations, rather than stem the tide of suffering.

It should be remembered that England became the world’s leading slave trading nation only after its ‘glorious’ revolution delivered greater political freedom to a much larger number of Britons. In the newly constituted United States, the revolutionary war of independence set blacks apart from whites by designating the former as ‘person held to service or labor’ (a coy euphemism for slaves) and extending their vassalage into the indefinite future. In South Carolina, the end of the external slave trade would kick off a period of remarkable growth in the domestic slave business, transforming Charlestown into the intellectual capital of the south’s sprawling cotton empire. At its peak in 1860, American slavers were overseeing a population of almost 4 million slaves, compared to the 1.5 million slaves plantation owners were left with a decade or so after the end of the external slave trade.[5]

The fact that the American slave population kept growing even after repeated efforts to slow the spread, degradation, and lethality of the institution was a sign to all Americans of good conscience that a new constitutional approach was needed to address the scourge of slavery. The question in 1856, as the sectional dispute over the morality of slavery reached its tipping point, was who among the nation’s political elite would be willing to risk his political career (and possibly life) to lead the feuding camps, come what may, toward a legislative resolution that would unequivocally assert the natural right of all human beings to the equal pursuit of life, liberty, happiness, and finally register to the civilized world the American people’s long-suffering outrage at this callous wastage of human life.

To clear-minded moralists, the institution of slavery was not just a stain on the country’s waterways, it befouled the very soul of America. No Washington politician spoke more clearly and forcefully about the evils of slavery and racial prejudice than Charles Sumner (1811–1874). In Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation, legal scholar Zaakir Tameez tells the inspiring story of how one man faced the rancor of the American slave oligarchy, and despite almost losing his life in the fight against race bigotry, not only won the political struggle to abolish slavery, but laid the moral foundation for desegregation and the triumphs of the civil rights movements.

Sumner is mostly remembered today as the man who was almost murdered on the floor of the U.S. senate for speaking out against the evils of slavery. Often forgotten is the moral vision which made this bookish lawyer a constant target of public hatred. Raised by a Harvard-educated lawyer and sheriff on the ‘black side’ of Boston, Sumner happily intermingled with Africans, racking up a large tab at the local black barbershop. Modern studies in both the U.K and the U.S have shown that repeated exposure to ethnic minority groups who share the same economic status and lifestyle as the white majority has a tendency to reduce feelings of xenophobia and racial prejudice—Sumner’s family was no exception. His father was also an abolitionist and an opponent of anti-miscegenation laws.[6]

In addition to the moderating effect of living among black people, Sumner’s religious upbringing taught him to cherish the equal worth and dignity of all people. In the antebellum years, he fought ferociously against the evils of slavery and frequently provoked Southern scorn on the Senate floor. After the Civil War, when race ‘science’ was emerging from the embers of Reconstruction, Sumner continued his fight against prejudice and discrimination.Tameez’s biography shows a Sumner who, throughout his life, chose to maintain his faith in the ‘‘Unity of the Human Family.’’[7]

When Sumner heard that the New Bedford Lyceum in Boston, Massachusetts, had refused to allow ‘colored persons’ to attend his scheduled lecture, the in-demand speaker cancelled his plans. On another occasion, he chose to politely withdraw from a paid appearance at the more prestigious Columbia law school in order to be an honored guest at the newly-instituted Howard School of law. Sumner was not just grand-standing: more than a century before the landmark 1954 Brown v Board of Education decision paved the way for black people to attend the same schools as white students, Sumner collaborated with the talented black lawyer, Robert Morris, to argue before the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, that black children should have equal access to public schools.[8]

The first high-profile black-white legal duo in American history, the pair introduced the idea of ‘‘equality before the law,’’ and in the same Roberts v City of Boston case of 1849 articulated the core argument for desegregation, namely, that a proper understanding of the claim that ‘‘all men are born free and equal,’’ entails that ‘‘no person can be created, no person can be born, with civil or political privileges, not enjoyed equally by all his fellow-citizens.’’[9]

Sumner would have the opportunity to argue for racial integration on more than one occasion. In the latter part of his life, Sumner would team up with another black attorney, John Mercer Langston, to introduce the Civil Rights Bill of 1870. The purpose of the bill was to ensure that all Americans (again, regardless of color) could have equal access to buses, trains, hotels, ‘‘theatres or other places of public amusement.’’ The exclusion of blacks from public venues was a particularly sore issue for Mr.Sumner, who in February of 1865 had to fight to get Dr. John Rock, an African-American doctor turned lawyer, admitted to the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, just to have the same man excluded from President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural ball in March of that same year.[10]

What in retrospect should have been a happy occasion—the abolition of slavery, the end of a long bloody civil war, and the re-election of the man who carried the hopes and dreams of an entire nation throughout this fiery ordeal—presaged the coming of another long and torturous fight for equality. It was already clear in the spring of 1864 that an embittered confederacy would not allow blacks to feel themselves ‘equal’ in any meaningful sense to the respectable white-majority. When Alexander Augusta, the nation’s first black military surgeon, was ejected from a street car in Washington, Sumner read the doctor’s letter of complaint on the senate floor, and proceeded to publicly demand that the government move to ‘‘uphold the human rights’’ of black people.[11]

Sumner was not the first U.S. politician to invoke the idea of human rights. In December 1806, for example, Thomas Jefferson called on the enlightened men of his age to remember the ‘‘human rights’’ of the ‘‘inoffending inhabitants of Africa’’ when the time comes to vote on the vexing question of whether to enforce the federal ban on the slave trade. Despite evidence of general revulsion at the barbaric nature of the slave trade, such moments of human rights advocacy and humanitarian feeling were rare. Most politicians, including Jefferson, had a very narrow view of what the human rights of black people practically entailed. What Tameez helps to show us is how Sumner stood apart in his holistic vision of racial equality.[12]

Most abolitionists were happy to fight for the civil rights of black people, meaning the ability to sue and testify in court, enter legal contracts, and acquire legal property. Some truly high-minded philanthropists were even willing to entertain the political rights of black people, welcoming the most qualified blacks as colleagues on the senate floor and vying for the votes of former slaves come election time. What was harder for many whites to accept was the idea that blacks had the same social rights as they did—rights to enter the same intimate societies, intermingle, and even intermarry within those circles.[13]

What made Charles Sumner a profoundly modern thinker was his commitment to a thorough-going conception of human rights based on the inherent dignity of all human persons. This universal, God-given worth, did not—in his view—preclude any black person from accessing the same services, products, and social goods as any other racial group. So understood, the abolition of slavery was in reality but one step toward a more comprehensive assertion of the equality of the races in every sphere of life.[14]

As Tameez explains, in ‘‘pushing for bills to open federal courts to Black testimony, permit black men to vote in Montana, and integrate Washington’s street cars, Sumner exhibited a belief in all three planes [civil, political, and social] of rights, which he united under the concept of human rights.’’ In fact, Tameez’s research suggests that Sumner used the concept of ‘human rights’ nearly three-hundred times throughout his political career, more than any other nineteenth-century political figure.[15]

Today, we most associate human rights with the presidential and post-presidential works of Jimmy Carter. What Tameez offers us in his biography of Charles Sumner is a visionary moral pioneer, willing to stake his legal and political career on the same such universal principles.

In May 1871, Sumner was awarded a gold medal by the government of Haiti for a lifetime of humanitarian work. The congratulatory letter, delivered by Stephen Preston, the Haitian ambassador to Washington, read: ‘‘You have protected and defended something more august even than the liberty of the blacks in America…It is the dignity of a black people seeking to place itself, by its own efforts, at the banquet of the civilized world.’’ To modern readers curious to discover how moral integrity can help activists secure political victories in the face of unlikely odds, this new biography of Charles Sumner offers a feast like no other.[16]

[1] Nicholas Radburn, Traders in Men: Merchants and the Transformation of Atlantic Slavery (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2023), 175.

[2] Radburn, 175.

[3] Sean M. Kelley, American Slavers: Merchants, Mariners, and the Transatlantic Commerce in Captives, 1644–1865 (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2023), 242; Radburn, 2;

[4] Radburn, 171; American Slavers, 185–186.

[5] David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press, 2006), 182.

[6] Zaakir Tameez, Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation (New York, N.Y: Henry Holt, 2025), 38–39; Maria Sobolewska and Robert Ford, Brexit Land (Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 54.

[7] Tameez, 429.

[8] Tameez, 91, 452.

[9] Tameez, 114.

[10] Tameez, 323, 330, 436.

[11] Tameez, 310.

[12] Kelley, 204.

[13] Kelley, 204; Sumner, 313.

[14] Tameez, 310–315.

[15] Tameez, 311–313.

[16] Tameez, 464.

Featured image is Charles Sumner