The Anatomy of Antiracism: Between Race and Class

When it comes to racism in the United States, there is a divide on the left between those who think we need a kind of spiritual reckoning, a full and honest confrontation with our past—with slavery, with racism, with something called “whiteness”—and those who think that it’s time to get on with building big-tent working-class coalitions between people of all races and focus on passing the kinds of social democratic policies that helped so many (mostly white) people reach the middle class in the mid-twentieth century. Although they are often pitted against each other as mutually exclusive approaches, there is more common ground between them than they often let on.

Those who foreground race underestimate just how much airtime our conversation about race—all the fine-grained distinctions, the academic squabbling that few Americans have time to indulge—takes up when we could be having more robust discussions about specific policies that help actual people, especially African Americans and other disadvantaged groups. But the reason many in this camp are often seen as thrusting race into the conversation is because they see a deep-seated racism as one of the primary obstacles to a more fruitful policy regime and think moral and spiritual progress is a prerequisite to any material or institutional progress.

People who prioritize class and multiracial coalitions think that the only thing we need to do is work toward passing better social democratic policies aimed at larger groups of people—especially the working class, which we tend not to think of as black, but which comprises a majority of black people—when some evidence paints a bleak picture about the likelihood of getting white people on board with these kinds of policies even when they are framed as race neutral and would benefit them. These thinkers have little issue with anti-discrimination legislation, the promotion of diversity, and activism that seeks to bring racism and its continuing legacy to more and more people, but they nonetheless think that an obsessive focus on these things misses the forest for the trees and distracts us from passing the substantive policies that materially help not just the disadvantaged but most people.

In the case of race reductionism—the disparaging term used by people who think we should focus more on class—we have a fairly typical leftist “paralysis of analysis” problem helped in no small part by the displacement of substantive politics by theory and a more performative kind of politics too concerned with policing language, the public shaming of individuals, and diversity trainings. In the case of class reductionism—the equal and opposite terms of disparagement used by people who prioritize race—we have the focus on policy, but a misunderstanding of just how deep racial animus runs and how much this animus actually hinders the passage of the very social democratic policies they want. When “Obamacare,” “crime,” and “welfare” are all immediately associated with “Black and brown people” in the minds of many Americans, any approach that attempts to sidestep these narratives is bound to be caught on their heels when confronted with what looks like people voting against their best interests.

Touré Reed and race reductionism

Touré Reed, author of Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism, thinks that our current obsession with race and our never-ending conversation—at least among elites—about all the ways in which race affects our daily lives works against the need to build broad working class coalitions that aim to help all people. “Liberals’ tendency to divorce race from class has had dire consequences for African American and other low-skilled workers,” he writes. “Specifically, race reductionism has obscured the political-economic roots of racial disparities, resulting in policy prescriptions that could have only limited value to poor and working-class blacks.” Reed thinks that this divorce comes from not only misreading what past movements for African-American equality and civil rights looked like, but from a widespread ignorance of how whites and other ethnic groups actually climbed the socio-economic ladder in the mid-twentieth century.

It’s true, Reed says, that Roosevelt’s New Deal policies failed to uplift African Americans to the same degree they helped working class whites, but “the now commonplace tendency to dismiss the Roosevelt administration’s crucial role in improving the material lives of millions of African Americans has obscured … the importance of the New Deal’s redistributive policies to blacks.” In refusing to see that the civil rights movements of the 30s and 40s were intimately wedded to labor concerns Reed thinks that successive movements for civil rights were less successful than they could have been. “For poor and working-class blacks,” he writes, “the harvest of Cold War–era civil rights politics was far less bountiful than it might have been had political and academic discourse on race and inequality remained rooted in political economy,” as it had been during the New Deal era.

So if you read the New Deal era as an utter failure for African Americans, then you will be tempted, as the Cold War liberals were, to take a new approach to the problem of racism and racial inequality, one in which race and ethnicity, rather than class, becomes the focus. To be sure, postwar liberals saw this move as a “radical departure from a tired liberal playbook that has ignored race and the importance of racial group identity,” but as Reed notes, this shift would be less than positive for most African Americans and “would ensure that African Americans would not receive their fair share of the fruits of the American welfare state, setting the stage for many of the disparities that animate progressives today.”

The divide, then, is between a New Deal order that placed racial inequality and racism “within a larger context of capitalist labor and social relations” and a postwar liberalism that viewed racism and discrimination as things that needed to be cast out of the hearts and minds of white people. With no small help from intellectuals like Oscar Handlin, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Nathan Glazer who thought that “ethnic/racial groups maintained particular cultural identities that warranted policymakers’ attention,” the postwar shift understated or ignored outright “the influence of political, economic and regional diversity over ‘black identity.’” This, according to Reed, also led thinkers to overstate just how effective a focus on race and ethnicity would be as a way to organize mass movements.

Successful civil rights campaigns—the March on Washington Movement of the 1940s, the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–6), the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom (1957), the lunch counter sit-ins (1960), the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Selma March (1965) and so on—all coalesced around specific policy aims rather than amorphous racial identity. And, of course, the modern civil rights movement’s judicial and legislative successes required a broad interracial base of support.

It was this socioeconomic approach to politics and organizing that led some of the earlier civil rights leaders to despair over the rise of black nationalist movements, though many of them understood why the shift occurred. Where black nationalism, according to some, went wrong was in thinking that previously marginalized ethnic groups, like the Irish or Jews, climbed the ladder due to the inner strengths of their own cultures—their local institutions and support structures—rather than state and federal policies that significantly impacted their economic opportunities and mobility, in large part because of their inclusion into the category of “white” as the century wore on.

Black Powerites’ insistence that ethnic culture was the engine of group progress would likewise lead many cultural nationalists to trace African American poverty to a combination of white racism and black cultural dysfunction—also known as the “culture of poverty” or the “ghetto underclass” thesis—a framework that would ultimately serve to justify welfare reform, mass incarceration and the privatization of public services, from housing to schools.

From Nixon on, Reed writes, “the view that racism is inextricably linked to economic exploitation began a steady slide into oblivion.” Fast forward to today and we see Black Lives Matter leaders criticizing politicians like Bernie Sanders for his supposed class reductionism. But on Reed’s account it’s historically inaccurate to say that “white liberals have long reduced racism to class inequality in order to deflect attention from racial disparities.” If this is true, many of the African American civil rights leaders of the first three-quarters of the twentieth century should be similarly scorned. This is not to say that we must be faithful to the old order, but rather the point is that groups like Black Lives Matter think they are doing something fundamentally new, when in fact, on Reed’s account, they are the ones deflecting attention from racial disparities, not in theory—since they are ostensibly targeting racial disparities head on—but in practice. Far from being new, today’s focus on ethnicity and race over and above class comes directly from the postwar liberal playbook.

No doubt many think that denying race as an independent force apart from class or political economy is little more than class reductionism, an evasion of the issue. But insofar as class has always been wedded to race, the idea of a pure class reductionism is a myth. As Adolph Reed Jr. writes, “the supposed view that inequalities apparently attributable to race, gender, or other categories of group identification are either secondary in importance or reducible to generic economic inequality” is not an idea that serious people on the left—or people who advocate for broad policies—hold. Since “Black, female, and trans people tend to be disproportionately working class,” any policies aimed at bettering the material circumstances of the working class will benefit the very minorities that people who put race front and center care most about helping.

“The bottom line,” Touré Reed writes, “is that the fate of poor and working-class African Americans—who are unquestionably overrepresented among neoliberalism’s victims—is linked to that of other poor and working-class Americans.” Antiracist efforts, then, should keep their sights trained squarely on political economy.

Making it about race

Brink Lindsey argues in a similar vein. While he agrees with nearly everything the left has to say about the disproportionate burdens born by African Americans in so many areas, he nonetheless thinks that the “race-conscious fashion” in which antiracists and activists frame every issue “is both unnecessary and counterproductive” and that the “heavy emphasis on changing hearts and minds, rather than reforming policies and institutions, is misguided.” These two problems, Lindsey claims, “misdirect the energies of social justice activism down pathways that are more likely to lead to backlash and empty culture war theatrics than real, positive change on the ground.”

Lindsey criticizes Ibram Kendi for presenting Americans with a racial ultimatum: you’re either racist or antiracist. Never mind that Kendi explicitly says that racist and antiracist are constantly-shifting modifiers depending on the specific issue or policy and not permanent labels for human beings, Lindsey thinks approaching the problem of racism in this way essentially “provokes defensive reactions and backlash.” When antiracists frame the issue as one of black disadvantage/white privilege they essentially reinforce a zero-sum picture: in order to help blacks, whites must lose. But white privilege, on Lindsey’s account, distracts us from two things we ought to keep in focus. The first is that our main concern should be black disadvantage, and the fact is that this doesn’t always depend on “white privilege” or even, necessarily, white people at all. The second point is the fact that not all whites have the “privilege” they are so often told they have. The fervent antiracist works hard just to convince the poor white worker that they are marginally better off than the poor black worker on account of their skin color, and in many cases that might not even be true. So what’s the payoff here?

Lindsey’s solution is to aim at policies that bring about racial equity and disproportionately help African Americans but are framed as racially neutral.

This option wasn’t available, of course, for the Civil Rights Movement against Jim Crow that culminated in the 1950s and ‘60s. At that time, Black people in the South—and elsewhere—were subject to de jure discrimination to enforce segregation and concerted, systematic state action to deny voting rights. It was therefore impossible to avoid addressing head-on the injustices that oppressed African Americans because those injustices were explicitly race-conscious. Yet even so, the path to ultimate victory lay in the movement’s strong commitment to framing its struggle in positive-sum terms: to allow Black people to enjoy the same basic rights that are promised to all Americans, and to move the country into closer conformity with the founding principles that all Americans embrace.

For Lindsey, battling for the soul of America—struggling to persuade people out of their racist attitudes—just distracts from the hard work of changing policies. “After all,” Lindsey writes, “the whole point of looking at racism in systemic terms is to shift the focus away from personal failings and misdeeds and toward broader social structures of oppression instead … Yet a great deal of the energy now expended in the name of anti-racism is directed toward identifying, calling out, and punishing individual malefactors.”

Here he points out, rightly, that progressives and conservatives differ on which way the policy-culture causation runs. Conservatives think that black culture primarily determines black outcomes, but progressives think bad policy drives most of the issues plaguing black communities. For progressives, if you take care of the policy, culture will take care of itself, to riff on Richard Rorty. Even while progressives believe this, they spend an inordinate amount of time channeling their antiracism “in renewed campus activism, initiatives by corporate HR departments to promote workplace diversity and inclusion, curricular changes in K-12 schools, and a seemingly endless parade of incidents and controversies on social media” rather than advocating for structural change in the form of policies that would benefit those whose welfare they ultimately care about.

The point is that antiracist efforts are “best pursued indirectly” as a function of broader policy changes aimed at larger groups. At the end of the day, framing policies as race-conscious is counter-productive, not only because of inevitable backlash, but because most policies that benefit blacks will also benefit other groups.

The costs of racism

Heather McGhee, author of The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, thinks that narratives like Reed’s and Lindsey’s seriously understate just how much the idea of government itself—and government spending in particular—has “become a highly racialized character in the white story of our country.” While the postwar focus on race and ethnicity spawned a whole host of tangents not directly related to the work of bettering people’s material lives, it wasn’t a completely unjustified shift in focus.

As McGhee recounts, one of the main obstacles to the kinds of policies Reed and Lindsey support is the zero-sum story that says if one group gains, another loses. Although Lindsey explicitly acknowledges the fact that we need to tell more positive-sum stories, he nonetheless seems to think this is simply about our policy framing rather than a substantive issue that requires more than just renaming a few bills or headlines. Lindsey understates just how closely this zero-sum story is tied to race, even and especially at the unconscious level: race-neutral policies—like the expansion of Medicaid, cheaper or free education, higher minimum wages, or just basic social democratic welfare policies—are still coded as race-conscious by many people. This dynamic means that white people will often, as the story goes, vote against their self-interest. In some cases, white people would rather not have affordable healthcare themselves if it means people who don’t look like them get it too—who are already, in their minds, getting generous handouts from the government.

Unsurprisingly, McGhee thinks that racism is the reason people apparently vote against their interests. McGhee writes that one day it sort of just hit her:

But what dawned on me, when I read the research showing that conservative white men tended to justify a system that had served them well, was that “the economy” being defended was not the textbook definition I’d learned: the sum total of our population’s consumption, goods, and services. That definition of the economy is one that could go on quite well and even flourish without white men being such lopsided beneficiaries. “The economy” that they were referring to was their economy, the economic condition of people like them, seen through the lens of a zero-sum system of hierarchy that taught them to fear any hint of redistribution. Value-neutral admonitions about protecting “the economy” allowed them to protect their own status while resting easy knowing that they were not at all racist, because it wasn’t about race—it was about, well, “the economy.”

On its face, looking out for one’s best interest (even if it means others unfairly being maligned) is a fairly typical human response to perceived scarcity—if it’s going to be a zero sum game, I should at least look out for me. But in-group preference, as bad as it may be in the long run, isn’t necessarily racist. What is racist is when in-group preferences are buttressed by feelings of out-group antipathy and stereotypes—which are, of course, given plenty of room to grow and breathe when groups don’t come into contact with each other. Zero-sum narratives entrench stereotypes.

The point, as Jonathan Metzl puts it in his book Dying of Whiteness, is that “white America’s investment in maintaining an imagined place atop a racial hierarchy” in many cases leads to terrible outcomes for white and black people. While it may be clear that this self-defeating dynamic is exacerbated by the twin forces of Fox News and conservative politicians fear-mongering about minorities and immigrants draining all of white America’s benefits, it’s less clear how we combat this zero-sum story. Lindsey seems to take it for granted that showing people that a particular policy is positive-sum will drive support for those policies, but it’s not clear that this is the case. Instead, the positive sum story—this will help everyone, yourself included!—may be covered by so many layers of racist ideas at this point that short of full-scale integration, people will continue to line up against policies that will undoubtedly better their lives. McGhee does a good job of explaining how the positive-sum story needs to be accompanied by days, months, years of integrated, cross-cultural communication and interaction—it’s not just an idea that needs to be blasted over the loudspeakers but a practice that needs to be nurtured and sustained.

The curious thing about stories like McGhee’s or Metzl’s isn’t that they think we ought to center race when analyzing social problems, but rather the fact that race just is front and center whether we like it or not. People like Reed and Lindsey who prioritize class tend to assume that focusing on race is a normative approach—and that we’d be better off if we talked about it less—when really race is seen as a kind of regrettable filter through which many Americans see politics. Since making race a thing seems to be precisely what’s keeping everyone behind, not just black people, it’s clear that many people who prioritize race in our current conversation aren’t exactly doing cartwheels over the fact that many Americans still cling to narratives—zero-sum, the lazy black worker, the welfare queen—that ultimately make everyone suffer except the most well off in society. There’s more to the story than racecraft—one cannot simply insist that anybody who focuses on race unjustifiably perpetuates racial division if the division is already there. As Ian Haney López argues in his book Merge Left: Fusing Race and Class, Winning Elections, and Saving America, “Because the Right has exploited racial division as its principal political weapon for five decades and counting, any practical conversation about American politics must name and discuss racial groups.”

This is the paradox: race-conscious framings reify race in a way that, both in the short and long term, seem bad for politics and policy, but ignoring race in order to pursue broader coalitions and policies may misfire since actual people frame things in racial terms anyway. The problem, López rightly points out, is that it’s just a fact that many people “filter the world through stereotypes and racist ideas.” As my colleague at Liberal Currents recently put it: “We’ll be talking about race regardless—there’s no putting that genie back into the bottle, and we should blame racism for that, not antiracism.”

Nonetheless, there’s a difference between saying that racism is the primary obstacle to passing more universal policies that help everyone, and saying black people are disproportionately disadvantaged and therefore we need more race-conscious policies aimed at helping black people in particular. Those who insist that we need to pass broad, New Deal-esque policies are lumping these two approaches together. While writers McGhee and Metzl agree that black people are disproportionately affected by bad policy, they are also the first to admit that they are by no means the majority who are affected in many cases—in terms of raw numbers, it’s white people who stand to lose most. This is Reed’s point when he says that African Americans weren’t the only victims of twentieth century housing policy even though they were overrepresented.

A racial reckoning?

The divergent approaches to the problem of racism depend on whether one believes that changing national sentiment is a prerequisite to changing national policies, or whether one thinks that it’s possible to enact policies without an underlying shift in sentiment. There’s a case to be made for the idea that culture is upstream from policy. There’s also a case to be made that policy is upstream from culture. It’s likely somewhere in between and any dogmatic commitment to one or the other ignores the complex reality and likely just serves to justify one’s own approach—a focus on hearts and minds or policy—in the broader antiracist movement.

To focus on hearts and minds, to foreground the fact that African Americans are disproportionately disadvantaged in nearly every social metric we care about, critics argue, is to invite unnecessary backlash and resistance. To focus on broader, big-tent policies underestimates the depth of everyday race-conscious framing of most issues. The divergent paths, if both criticisms are legitimate, both lead back to the same place: the need for a racial reckoning—a full and honest confrontation with our past and continuing racism and how, ultimately, racism holds everyone back.

A racial reckoning need not be a single-front battle, however. Like most things, complex problems require multi-pronged solutions. The back and forth between these different fronts—between leftists and liberals, policy wonks and culture warriors—causes a lot of unnecessary friction in what is ultimately the same war with the same objective. This is not to say that internecine arguments over tactics aren’t fruitful—they are—or that accusations of taking up too much air time aren’t true—it’s a legitimate concern—just that we could all probably ease up a bit more about whether or not someone shares our agenda when pursuing antiracist goals.

On the one hand, Brink Lindsey is right that “a great deal of the energy now expended in the name of antiracism is directed toward identifying, calling out, and punishing individual malefactors.” More to the point, it’s not even clear that this strategy works. On the other hand, I do think that passing broader policies with racially inclusive framing is the best way forward.

Near the end of his book How to Be an Antiracist, Ibram Kendi offers a challenge to antiracists seeking to change people’s minds: “What if we measure the radicalism of speech by how radically it transforms open-minded people, by how the speech liberates the antiracist power within? What if we measure the conservatism of speech by how intensely it keeps people the same, keeps people enslaved by their racist ideas and fears, conserving their inequitable society?” Racists and racist power, Kendi goes on, use any and all means necessary to entrench and uphold inequities.

We, their challengers, typically do not, not even some of those inspired by Malcolm X. We care the most about the moral and ideological and financial purity of our ideologies and strategies and fundraising and leaders and organizations. We care less about bringing equitable results for people in dire straits, as we say we are purifying ourselves for the people in dire straits, as our purifying keeps the people in dire straits. As we critique the privilege and inaction of racist power, we show our privilege and inaction by critiquing every effective strategy, ultimately justifying our inaction on the comfortable seat of privilege. Anything but flexible, we are too often bound by ideologies that are bound by failed strategies of racial change.

Even Ibram Kendi thinks we liberals and leftists need to be more flexible, understanding, compassionate, pragmatic, and perhaps most of all engage with people where they’re at, on their own terms, as difficult as that may be. Kendi is right to point out that many antiracist efforts are as conservative in effect as they are progressive in intent. Many on the left simply refuse to lend any credence to conservatives’ experiences and genuine concerns, so conversations on race don’t last very long. This is rarely because the person on the other end is an irredeemable white supremacist, but very often because the tools, vocabularies, and methods antiracists bring to the table put people on the defensive. This doesn’t mean antiracists should pack away the concepts they find useful in their own analyses, but they should understand that public conversations—often between strangers—require something else, perhaps nothing like what informs their own antiracism. Perhaps most important, culture warriors need to understand that changing sentiment is a difficult and long-term game—moral reformers rarely see the fruits of their efforts in their own lifetimes.

Racial disparities and better frames

Kendi argues that in order to “fix the original sin of racism” the U.S. needs to “pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principles: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals.” The amendment would “establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees.” The main purpose of the DOA would be to preclear “all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas.”

At an institutional level, this strikes me as unserious and even silly, though I understand the sentiment behind it. But as a general framework for approaching policy it’s actually quite useful. If Reed and Lindsey want race-neutral framings of policy so that they don’t provoke backlash and help those most disadvantaged, then we have to be honest about the history of those kinds of policies. Kendi’s suggestion that we be sensitive to disparate outcomes rather than whether a given policy looks and sounds good as a way to avoid this problem.

One way to read what Kendi is saying is that there should be a presumption in favor of thinking that racial inequities or unequal racial outcomes are the result of specific racist policies. The history of racism in this country—at least from Reconstruction onward—has been the history of race-neutral policies specifically designed, framed, and worded so as to preclude charges of racism while at the same time producing racist outcomes—that was the whole point. To combat the insidiousness of these kinds of things, not only are outcomes paramount in our analysis, but it seems that a presumption in the direction of racial inequity isn’t such a radical lens but rather a fairly commonsense one. Of course, it’s just one lens among many, but it’s an important one.

Kendi would probably push back against this softening of his maxim to a mere presumption, but my presumption argument seems to map onto Kendi’s overall framework since, in spirit, the Department of Anti-racism’s main goal would be investigating racial inequities in order to determine if there was racist policy at work or whether a policy would disproportionately harm African Americans or is currently harming them. On my account, we leave the door open for racial inequities that are neither due to racist policies nor further major disparities. Leaving this door open may placate those who think Kendi uses far too blunt a principle in trying to stamp out racism. If Reed and Lindsey are serious about passing broad policies, they shouldn’t object to this.

So what this all comes down to for Kendi this comes down to a kind of policy-reductionism, which, for many people, has the picture exactly backward. “Americans have long been trained to see the deficiencies of people rather than policy,” Kendi writes. “It’s a pretty easy mistake to make: People are in our faces. Policies are distant. We are particularly poor at seeing the policies lurking behind the struggles of people.” Kendi thinks that this is, in part, the reason why people turn from policy to strategies aimed at cultural uplift and betterment, which in turn imply that there is something inherently deficient with a particular group. Rather than see the looming policies, past and present, we tend to fault people for their problems. I think Kendi is right about this, if only from a psychological point of view. Policy is hard. Determining the implications and effects of policy even harder. Judging people’s habits is easy—trivially easy—and so devising “solutions” to those bad habits seems less daunting—and a lot cheaper—than devising policy solutions.

Not only do we need to be sensitive to policies that produce racial disparities, but taking a line from Ian Haney López’s book Merge Left, we need to fight the right’s racist dog whistling and scapegoating of minorities and immigrants with more powerful (and truthful) policy frames that explicitly acknowledge that all races—black, white, and brown—stand to benefit from these policies, and that the largest obstacle are the greedy career politicians, lobbyists, and corporations who use race to divide and distract us. As my colleague puts it: this framing “preempts the rightwing racialization and provides a plausible villain (the rich and powerful) to replace the scapegoat role performed by Blacks, immigrants, and other Others.”

No easy task

Any serious anti-racist project must take seriously implications of our segregated way of life and, as Elizabeth Anderson puts it, “the imperative of integration.” This means the current debate over framings and press releases tends to overstate the degree to which people are simply responding to institutional rhetoric. It might be the case that a significant number of people would be swayed if policies weren’t introduced as beneficial for disadvantaged minorities, but given the fundamental paradox above, it’s not clear that this is the majority of people. When a neutral-sounding policy gets blasted across the headlines or White House press releases, and millions of people think to themselves, “this is just another plan to help the minorities” then the problem runs deeper than PR.

The themes in McGhee’s book still loom large over the entire conversation. Changing people’s minds is hard, and likely impossible on Twitter—at least at the pace we’d like them to. Even more, race relations are going to continue at a snail’s pace so long as segregation remains the norm in the U.S. Whether one wants to focus on the broader culture or specific policies, this fact can’t be ignored. McGhee’s book is peppered with stories of success and failure—in local communities, in movements for unionization, in fights for better wages. The crucial task is to bring people together—this might be the most crucial aspect of the antiracism agenda—not simply to change the PR of certain policies. Without deeper subterranean changes in sentiment through integration, it’s possible that even race-class framings could get hijacked by race-conscious framings (e.g. “The left will tell you it’s about black, white, and brown, and that the true enemies are in Washington and Wall Street, but they don’t mean it! Socialism! Communism!”)

If those who would change hearts and minds continue to polarize and those who would ram through policies continue to be stymied when “popular” policies are shot down, we are thrown back on the fact that a racial reckoning needs to happen on the ground—face to face, in person, patiently, and meeting people where they are at. And it will be difficult, but there is hope; there are hundreds of books, including McGhee’s, that document the trial and error nature of bringing people from wildly different backgrounds together for a purpose, a goal, or just a conversation.

Without actually bringing people together to mingle, to relate to each other’s stories, to see similarities and take genuine interest in people’s differences, to empathize, we will continue to travel down this road where stereotypes persist. Government handouts will still be synonymous with black and brown people and white privilege will be as unhelpful as it is marginally true to many struggling white people—even if this struggle was largely self-inflicted.

What both sides in this fight tend to overlook is the fact that often this is less about framings and tactics and more about the fact that many people don’t encounter people who look different than them—a much more difficult problem to tackle, but one crucial to the antiracist agenda.

Until either integration or highly integrated movements and campaigns become the norm, it’s not clear how much reframing will do. Actual integration is a much more difficult task, and movements for some specific thing will likely benefit from including everyone in the conversation, even people who it might not affect directly or to the same degree or even those who disagree entirely. This isn’t a recipe for success, it’s a recipe for democracy, and it’s not clear we have any other choice.

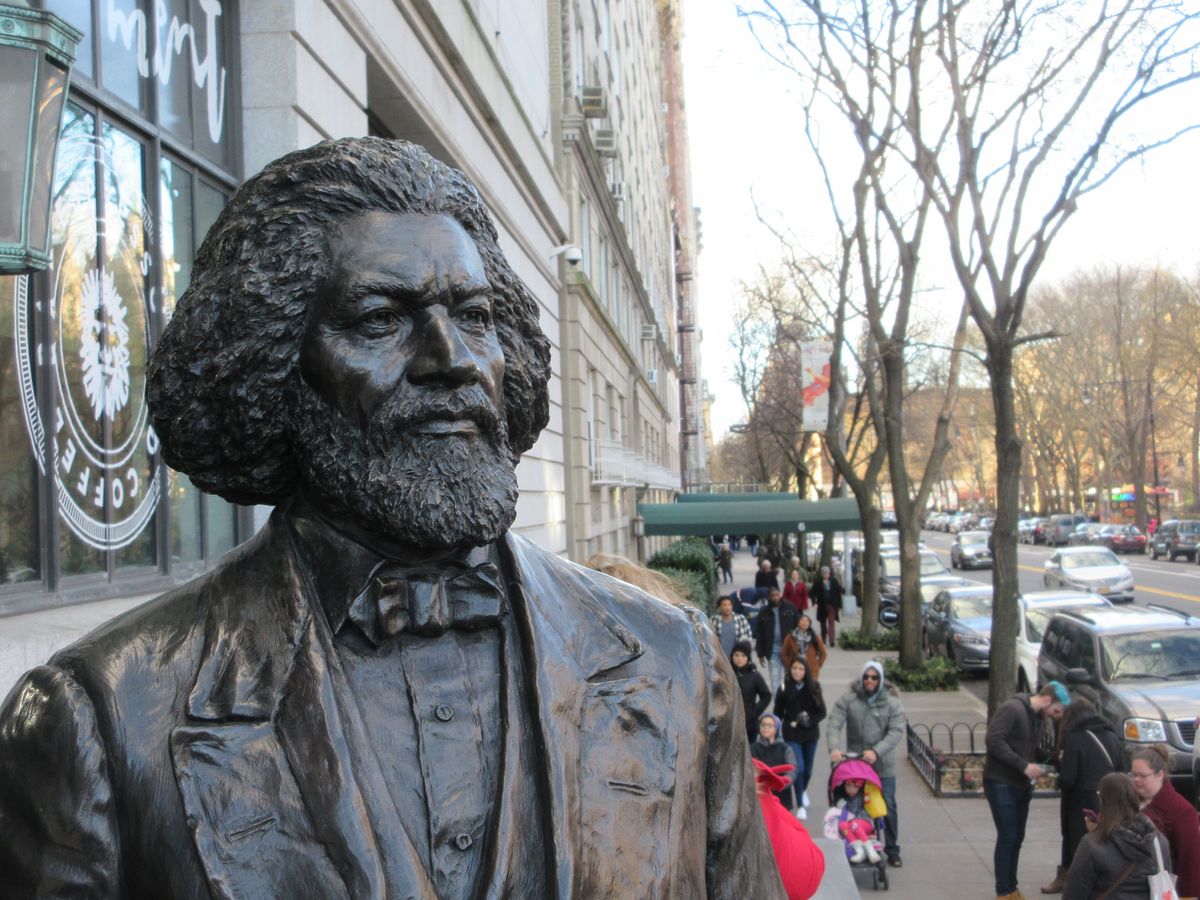

Featured Image is Frederick Douglass Abolitionist Bronze Statue NYC, by Brecht Bug