The Banality of Complicity: Arendt's Guide to Moral Resistance in the Age of Trump

Even in seemingly powerless positions, the choice to withdraw one’s support from corrupt systems remains a meaningful assertion of humanity.

After living more than 10 years under an assumed name in Argentina, Adolf Eichmann, a former high official in the German army, was abducted by the Israeli Mossad and transported to Israel in May 1960 to face charges of crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The next year, Eichmann was tried as the mastermind of the Final Solution. His defense was meager—Eichmann would claim that he was simply following orders, a defense that had been tried at Nuremberg but failed—and the result of the trial seemed predetermined from the moment of his abduction. Eichmann would hang for his responsibility in the Nazi slaughter of six million Jews.

The trial is most remembered today for giving rise to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), originally a series of essays for the New Yorker magazine. The book became the subject of highly charged debates that served as a proxy for adjudicating the responsibility of many two decades earlier. Arendt was attacked by those who mistook her account of Eichmann’s banality as a person to mean somehow his acts were such; by those who thought she underplayed Eichmann’s virulent and murderous antisemitism to render him as a cliché-addled bureaucrat; and by those who felt her far too critical of those, including members of the Jewish councils (Judenräte), who cooperated with the Nazi regime. In particular, critics were inflamed by Arendt’s claims of Eichmann as “banal” while pointing her ire in many passages on “victims” of the regime. Critics accused her of not having enough of an understanding of the realities of life under Nazi occupation. But while there’s room to argue with Arendt’s historical claims and her depiction of the character of Eichmann, the idea that she didn’t understand the plight of living under such a regime was a contemptible lie.

While still in Berlin, Arendt had secretly carried out research for Kurt Blumenfeld, secretary general of the Zionist Federation of Germany, on the antisemitic propaganda being rushed to print by various German business and civil groups believing in or at least wanting to be seen to parrot the new regime’s views on World Jewry. Arrested by the Gestapo for her efforts, she was interrogated over eight days (she told the police only a parade of lies about those with whom she had been in contact), and upon her release fled with her mother without travel documents on a perilous journey to Prague (whose Jewish population ballooned as it was a stopping point for those escaping persecution), then Geneva, and then to Paris. In Paris, she would live as a stateless refugee working for Jewish organizations working to find safety for the many refugees fleeing Nazi Europe. In May of 1940, Arendt's life would be upended again as the Vichy regime in France, collaborating with Nazi Germany, classified her and other Jews as “enemy aliens.” She was interned at Gurs concentration camp and forcibly separated from her husband Heinrich Blücher, who was detained in a camp near Paris. In mortal danger, Arendt managed to escape from Gurs in July and eventually reunited with Blücher, who had also fled his internment. The couple spent four harrowing months in hiding, at risk of being discovered by Vichy authorities, before securing emergency American visas. Their journey to freedom took them through Lisbon, where they waited several months before finally reaching the U.S. in May 1941. (The writer Walter Benjamin attempted the same route shortly after, but facing arrest at the French-Spanish border, he took his own life rather than face what the Nazis had in store for him.)

Thus, while many critics asked who she was to judge those who remained in Germany and made many compromises to survive, Arendt knew from direct experience the dangers faced from the fast-changing morals of societies—first Germany, then France—that had fallen under humanity’s worst. As for who is in a position to judge such things, Arendt provided an extended answer in the form of a lecture in 1964, “Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship,” while still reeling from much of the public controversy over the Eichmann book.

To read it now is to be assailed on all sides by the claims on each of us under the Trump regime, and that there is no twisting free of these responsibilities. Any excuses we might hear for bending the knee to the second Trump administration are held up and whither instantly under her criticism. The essay reads is uncanny in precisely identifying the psychological and moral patterns of capitulation and cooperation we see playing out today.

That said, what makes her work so powerful isn’t its prescience but her profound understanding of how such authoritarian systems corrupt us from within. Arendt observes the alarming speed with which moral standards can be inverted overnight. “All our experiences tell us that it was precisely the members of respectable society, who had not been touched by the intellectual and moral upheaval in the early stages of the Nazi period, who were the first to yield,” she says in the lecture. “They simply exchanged one system of values against another.” These supposedly “good citizens” didn't resist but adapted with disturbing ease to new, corrupt norms.

Equally troubling is Arendt's insight into how readily people surrender individual judgment to systems. By transforming themselves into mere “cogs” in a larger machine, they absolve themselves of personal responsibility. This psychological abdication offers both a self-rationalization and a defense. Perhaps most surprising is Arendt's observation that it was neither the elite who had greater power to resist nor those with the strongest previous moral convictions—these groups often fell quickly into line. Rather, resistance frequently came from skeptics and others who seemed to lack any previous strong commitments at all. Their moral clarity emerged not from established ethical frameworks but from a fundamental, uncompromising sense of what they could live with—and what actions would make it impossible to live with themselves.

The lecture isn’t some grandstanding harangue about the need for heroism. Instead, she makes clear that resistance begins not with heroic action but with the simple refusal to participate in the regime and its lies, as well as the comfortable self-deceptions that make complicity possible.

What critics misunderstood about Eichmann in Jerusalem was seeing it as critical of those who had to suffer under Nazi rule instead of an empowering treatise on resistance, with its constant reminder that even in seemingly powerless positions, the choice to withdraw one’s support from corrupt systems remains a meaningful assertion of humanity. As such, the historical context for the lecture is as crucial as the biographical background of the controversies around Eichmann: Arendt was addressing the moral questions that arose during the postwar trials of Nazi officials, particularly how ordinary people were complicit in extraordinary evil.

Today, most Americans who think of postwar punishments of the Nazis recall the trials and verdicts at Nuremberg. However, Arendt’s lecture was given in the years when a pattern had emerged in which former Nazis responsible for unspeakable horrors were given appallingly light verdicts. For those who look to the judgment of history as a kind of emotional salve during dark times, this period serves as a clear rebuttal to any belief in inevitable moral progress toward a point when history will judge the past rightly. That future, too, has to be fought for.

In the last 1950s and early 1960s, German judges insisted that Nazi-era crimes could be tried only according to the standards of law valid at the time they were committed, which usually led to acquittals or minimal sentences. The fact that it was Israel, not Germany, that brought Eichmann to justice highlights precisely what Arendt was arguing. In this context, Arendt's lecture becomes even more palpable—not only had countless ordinary Germans supported the regime through their actions, but the postwar legal system then provided another layer of protection through its narrow interpretation of culpability. If you’re worried that a future U.S. administration will again argue for turning the page on the crimes committed in our name, Arendt’s lecture is there to share your scorn.

At the beginning of the lecture, Arendt describes a deep disappointment many had as they watched an entire population capitulate so quickly:

I had somehow taken it for granted that we all still believe with Socrates that it is better to suffer than to do wrong. This belief turned out to be a mistake. There was a widespread conviction that it is impossible to withstand temptation of any kind, that none of us could be trusted when the chips are down, that to be tempted and to be forced are almost the same.

At this point, Arendt quotes Mary McCarthy as saying, “If someone points a gun at you and says ‘Kill your friend or I will kill you,’ he is tempting you, that is all.” Though the scenario can seem histrionic or, indeed, irresponsible, it wasn’t. Here is a passage from Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism where she discusses how the terror of Nazism produced a singular dehumanization that’s as impossible to fathom as it is a historical reality:

Totalitarian terror achieved its most terrible triumph when it succeeded in cutting the moral person off from the individualist escape and in making the decisions of conscience absolutely questionable and equivocal. When a man is faced with the alternative of betraying and thus murdering his friends or of sending his wife and children, for whom he is in every sense responsible, to their death; when even suicide would mean the immediate murder of his own family—how is he to decide? The alternative is no longer between good and evil, but between murder and murder. Who could solve the moral dilemma of the Greek mother, who was allowed by the Nazis to choose which of her three children should be killed?

Against all this, McCarthy’s example at least offers some level of humanity left. And while certainly extreme, anyone who considers the dilemma for a moment realizes what it would mean to choose a loved one’s death over yours—to choose, per Socrates’ dictum, causing harm to another over having it done to you. Given this starting point, it isn’t difficult for Arendt to show all the petty inconveniences one might throw up as excuses—a giant law firm might lose clients, a university complaining too loudly about what’s happening to its students could lose too much in funding, etc.—are profoundly unserious by comparison.

She then moves one by one through the claims of those downplaying the responsibility of those caught within the “moral collapse” of the Nazi regime: that one is but a cog in a much larger machine; that one was just following orders with no real agency or responsibility; that there was collective guilt for the Germans (which manages to make no one in particular responsible and thus makes no one guilty); that one was simply swept up in the "spirit of the times" or caught in historical forces beyond individual control; that one was a “law-abiding citizen”; that one’s acts wouldn’t make a difference; and, finally, that one was simply acting out of fear for one’s safety, which Arendt notes was rare—surprisingly few, in fact, had guns to their heads, at least among those she’s discussing.

Arendt then points out that it wasn’t as if the moral status of the regime was a problem for onlookers:

We were outraged, but not morally disturbed, by the bestial behavior of the storm troopers in the concentration camps and the torture cellars of the secret police, and it would have been strange indeed to grow morally indignant over the speeches of the Nazi bigwigs in power, whose opinions had been common knowledge for years.

She doesn’t mean, of course, that Nazism wasn’t a moral horror; it’s just that few things are easier than deciding upon the morality of Nazis. The moral weight upon each person came from elsewhere:

The moral issue arose only with the phenomenon of “coordination,” that is, not with fear-inspired hypocrisy, but with this very early eagerness not to miss the train of History, with this, as it were, honest overnight change of opinion that befell a great majority of public figures in all walks of life and all ramifications of culture, accompanied, as it was, by an incredible ease with which lifelong friendships were broken and discarded. In brief, what disturbed us was the behavior not of our enemies but of our friends, who had done nothing to bring this situation about. …. Without taking into account the almost universal breakdown, not of personal responsibility, but of personal judgment in the early stages of the Nazi regime, it is impossible to understand what actually happened.

No doubt, this passage has some very prominent examples from these past few months racing through your mind. Particularly dispiriting in Arendt's account is how quickly she says one’s conscience can be co-opted by an authoritarian regime. “It was of great political relevance," she had written in Eichmann in Jerusalem, “to know how long it takes an average person to overcome his innate repugnance toward crime.”

A crucial rationale used early in the Nazi regime and one heard today was that, as Arendt puts it, “if you are confronted with two evils… it is your duty to opt for the lesser one, whereas it is irresponsible to refuse to choose altogether.” Yet Arendt quickly notes the catastrophic morality of this position: “those who choose the lesser evil forget very quickly that they chose evil.” More insidiously, the “lesser evil” argument didn’t just provide external justification but was “one of the mechanisms built into the machinery of terror and criminality.” Authoritarian regimes deliberately employ this logic as a conditioning tool, implementing horrors incrementally, she argues. This kind of “psychological grooming” allowed ordinary citizens to participate in extraordinary evils while maintaining their self-conception as morally good—after all, they didn’t choose the worse evil—effectively dismantling their ethical resistance one compromise at a time.

Pretty soon, you’re replacing an imagined set of commands for your own conscience. In crucial passages from Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt worked through parts of Eichmann's interrogations where he discusses elevating the laws of Hitler to the status of a perverse moral imperative. For Kant, the categorical imperative requires that one act only according to maxims that can become universal laws—principles that would make sense if everyone followed them, regardless of personal desires or circumstances. But Eichmann told his Israeli interrogators that, rather than following his own moral reasoning, he viewed his moral responsibility to be acting as if the Führer were there to approve what he was doing. Thus, bureaucratic functionaries need not feel guilty for carrying out atrocities if they’ve simply replaced a fantasy of a leader’s decisions for their own. This is what enables ordinary people, not the fantastic monsters of horror films, to participate in evil—such acts become matters of duty and professional obligation.

With such complicity in the background, one might be surprised by Arendt’s relative sympathy for those who typically receive much of the criticism: the “nonparticipants” who chose internal withdrawal—what Germans called “Innere Emigration.” These were the intellectuals, artists, and ordinary citizens who remained physically in Germany during the Nazi period but deliberately withdrew from public life, abstaining from supporting the regime in every way possible. While outwardly an abdication of political responsibility, their stance puts the lie to the claims of many that complicity with the regime was inevitable.

To those who think we need the punishment of the judgment of history for those tempted to comply with authoritarian regimes, Arendt offers something far more personal and down to earth, describing those who resisted as “ask[ing] themselves to what extent they would still be able to live in peace with themselves after having committed certain deeds.”

Having knocked down the last of the excuses of the complicit—what else was I to do?—Arendt can move to the central claim of the lecture: that “obedience” always amounts to support, no matter what we tell ourselves to sleep at night.

We have only for a moment to imagine what would happen to any of these forms of government if enough people would … refuse support, even without active resistance and rebellion, to see how effective a weapon this could be. It is in fact one of the many variations of nonviolent action and resistance—for instance the power that is potential in civil disobedience.

This redescription of obedience and complicity as support is perhaps the most salient point for us today. We should refuse the comfort of passive language that allows individuals to distance themselves from their actions. The bureaucrat who processes deportation orders, the lawyer who drafts legal justifications for renditions to El Salvador, the writer who normalizes extremism with cheery prose about administration moves—all are actively supporting systems they claim merely to serve.

But so, too, are those who think there’s nothing to be done, that the future is a fait accompli. Arendt is scathing about something Adam Gurri, Josh Marshall, and others have critiqued as the “doomerism” of some on the left—the savvy know-it-alls ready to pipe in about how they saw all the horrors of today coming years ago and now dismiss any talk of elections in 2026 as a naive distraction from the ineluctable consolidation of authoritarian rule. In Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt argued that such “savvy” takes show a fundamental misunderstanding of reality:

Comprehension [of what’s happening] does not mean denying the outrageous, deducing the unprecedented from precedents, or explaining phenomena by such analogies and generalities that the impact of reality and the shock of experience are no longer felt. It means, rather, examining and bearing consciously the burden that events have placed upon us—neither denying their existence nor submitting meekly to their weight as though everything that in fact happened could not have happened otherwise. Comprehension, in short, means the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality.

Acceding to the inevitable—“doomerism”—is just another means of supporting the unsupportable. No doubt, such fears of our collective futures aren’t unfounded, but they shouldn’t be allowed to cohere into what amounts to support for what we face today. It’s simply another way of switching to the historical or inhuman scales when, in fact, the true moral question is about the weight of responsibility that falls upon each of us, while acknowledging that we exist within a web of relations with others. What makes Arendt’s “Personal Responsibility Under a Dictatorship” essay so profound is that she locates resistance not in grand gestures requiring extraordinary heroism, but in preserving one's capacity to think independently and refuse complicity in evil even when everyone else has capitulated.

We cannot control the circumstances we inherit—so many never asked for this—but we always retain the power to withhold our support from systems that violate human dignity. And in that vital first act of defiance lies the seeds for resisting the reality in which we find ourselves today.

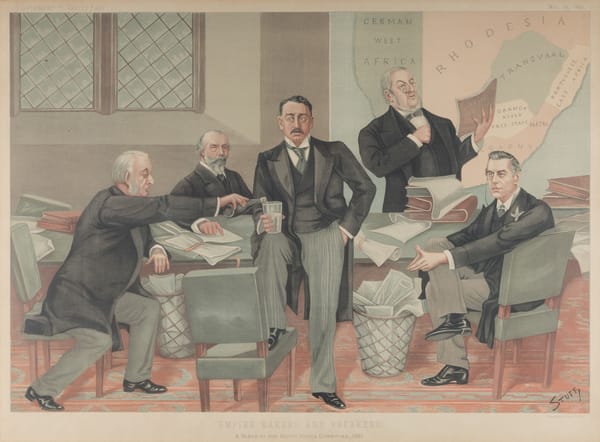

Featured image is The Appeal of Nazi War Criminal Adolf Eichmann