Free Trade, Free Movement, and the Cosmopolitan Coalition

Theirs was a vision of a world united in peace, in a federation of democratic states (if not a world state), with no barriers to the movement of goods and free, enterprising human beings, the baleful presence of oppression, inequality, and inherited privilege long forgotten.

The Manchester liberals get a bad rap. These 19th century liberals were those unfeeling, doctrinaire “little Englanders” who espoused individualism and economic laissez-faire, disregarding the interests of the worker and the poor in favor of the sanctity of contract between individuals. They were the stand-in libertarian bogeymen before Ayn Rand came along to show us there was still a little subtlety to wring out of capitalist ideology. It’s true. John Bright and Richard Cobden, the brightest stars in the Manchester firmament, did defend laissez-faire against what many today think of as common sense interventions.

Yet there is another story, one where the Manchester Liberals—liberal radicals—formed the core of an international left-wing movement driven by concern for the hungry, the vulnerable, and the powerless, and by resentment against the unearned rents and privileges of the rich and powerful.

This is the story of Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free Trade World, by Exeter historian Marc-William Palen. Long the economic campaign of the right and neoliberal center, free trade got its wings on the political left in a diverse coalition. Palen brings together liberal radicals, socialists—including one Karl Marx—Georgist single-taxers, feminists, and Christian social reformers.

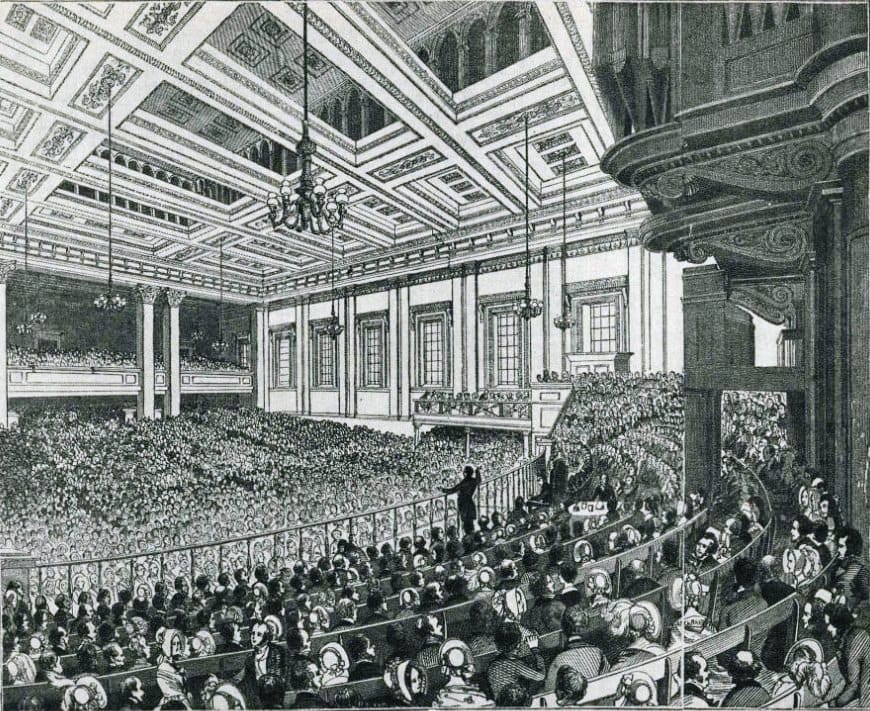

The left-wing logic of free trade is clear enough in its Manchester origin. In 1838, Liberal members of Parliament Bright and Cobden formed the Anti-Corn Law League, committed to abolishing the tariffs on imported grain. Palen summarizes the explicitly anticipated effects free trade would have:

And the Manchester School’s staunchest left-leaning ideologues believed that the market interdependence wrought from the worldwide adoption of free trade would bring a panoply of riches: prosperity; industrialization; the devolution of empires; the eradication of hunger by expanding the global food supply and lowering food prices; and the democratization of governments by undermining the political power of militant mercantilist elites. For Manchester liberals, free trade thus offered an intoxicating cure-all for an industrializing world plagued by inefficient markets, aristocratic rule, mercantilist empires, food insecurity, and geopolitical turmoil.

The “laissez-faire” of free trade was thus less an ideological commitment to the free market or a desire to give free rein to rich capitalists as it was an effort to feed the poor, foster world peace and cosmopolitan friendship, and erode the baleful and unjustly got power of land-owning aristocrats.

These left-wing values attracted other leftist groups with their own ideological agendas. The coalition firmed up on the basis of natural synergy with a set of interlocking issues. Palen’s book is organized by ideology, with a chapter devoted to each coalition member, but the same set of synergistic issues kept coming up in each chapter.

Peace and anti-imperialism were foremost among these. In Cobden’s formulation, free trade would create an interdependent economic order that would remove “the desire and the motive for large and mighty empires; for gigantic armies and great navies.” Socialist internationalists associated the protectionism of the expanding industrial capitalist powers with militarism and imperialism. When you can’t acquire raw materials and markets by trade, you have to seize them by force. Women’s peace activists like Jane Addams—inaugural president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and who coined the phrase “Pax Economica”—viewed economic protectionism as a covert war. Campaigning for free trade jived with their peace agenda. Christian activists overlapped with women’s groups in these motivations, and sometimes with the groups themselves, as with the influential Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), which had a direct line with President FDR’s secretary of state—”America’s Cobden”—Cordell Hull.

When imperial powers were jockeying for power in the 19th century, there were none of the international governing and diplomatic institutions we’re familiar with today. The campaigns for free trade and peace naturally led to campaigns for supranational governing entities. These campaigns would culminate in the League of Nations and later the United Nations. Dreams of a “United States of Europe” that would finally end Europe’s violent conflicts and secure free trade were shared by these same left-wing campaigns deep in the 19th century.

The “open door” to free trade was often accompanied by “open borders.” The same cosmopolitan sentiments that facilitated trade with other peoples and drove concern for the victims of mercantilism and war also opened hearts to immigration. Socialists saw free trade and free movement both as a means of uniting the workers of the world. Christian support for open borders grew out of a deep ethical tradition of hospitality for the stranger and support for refugees.

Henry George’s land value tax (LVT) was something of a surprise recurring guest star in Palen’s history. It’s not immediately obvious that parties as disparate as liberals, feminists, and Christians would all be attracted to what today seems like a forgotten policy of interest primarily to niche tax wonks. Yet the free trade coalition aimed to cut off a significant source of revenue. What better way to replace the lost revenue than to target the land monopolists who sustained mercantilism, threatened food security, and agitated for imperial expansion and war?

The landed gentry thrived on the unearned rents accruing their exclusionary ownership of land, a naturally occurring but finite, necessary resource. The logic of the strange bedfellows coalition of free traders and land taxers snaps into place when we see that laissez-faire and land taxes are both in their respective fashions assaults on rentier politics—on the politics of hoarding advantage by excluding others.

The connections were pervasive. Georgist suffragist Elizabeth Magie, with financial backing from another free trade feminist, Mary Fels, patented The Landlord’s Game. One of her neighbors, the socialist professor Scott Nearing, used it as a teaching aid with his students at the University of Pennsylvania. And it would eventually go on to be rebranded as the Monopoly we know and love today.

In another amusing anecdote illustrative of the Georgist-free trade connective tissue, New York Catholic priest Edward McGlynn was “excommunicated for his Georgist beliefs, and then ordered to travel to Rome to explain his adherence to this brand of economic liberalism, social justice, and peace.” Henry George himself published a hundred-page open letter to Pope Leo XIII arguing that “the principle of the single tax was ‘a conforming of human regulations to the will of God’, whereas protectionism ‘sanctifies national hatreds’ and ‘inculcates a universal war of hostile tariffs’ and was thus opposed to Christianity’.” McGlynn’s excommunication was lifted.

A black hole in the coalition

The above hardly does justice to the spider’s web Palen weaves, connecting liberal radicals, Georgists, suffragists, socialists, and Christian reformers to each other through the common threads of free trade, open borders, land reform, world peace, supranational government, and democracy. Yet reading Pax Economica, one left-wing group was conspicuously absent from this social justice coalition: black Americans.

This is especially curious because each of these coalition partners had roots in the antislavery movement and the campaign to abolish the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Yet black commentary on trade policy seems oddly hard to unearth. Palen does discuss W.E.B. du Bois, who was a vocal protectionist, being a student of the German Historical School associated with Gustav Schmoller, Max Weber, and the earlier American economist, Friedrich List (if any figure is a villain in Pax Economica, it would be List).

From my own research I was familiar with the surprisingly fervent opposition to free trade by the legendary American liberal and antiracist, Frederick Douglass. Appealing to an “infant industry” argument, Douglass argued that free trade might work for the mature industries of Britain, but not for America’s supposedly more vulnerable capitalists. From the other end of the socioeconomic ladder, Douglass argued that free trade would depress wages of the poorest American workers, particularly black laborers. Despite this apparent ideological difference, it’s worth noting that Douglass expressed the highest esteem for Bright and Cobden, who had both welcomed and feted him when he visited the UK as a fugitive slave in the 1840s.

Of course there are counterexamples. The anti-lynching activist Ida B Wells suggested the Republican obsession with the protective tariff was a distraction from their abandoned support for human rights. Booker T Washington insinuated that blacks only opposed free trade because they were beholden to the Republican party.

I offer this detour as a warning about the double-edged nature of coalitional politics. Washington’s tone was patronizing, but there is some truth in the observation that for as long as the Democratic party was resolutely white supremacist, it would be difficult for black Americans to speak out against the beloved tariff of the northern Republicans too forcefully, whether or not it served their material interests as a policy.

Cosmopolitan synergy

With that warning in mind, the story of free trade offers a tantalizing glimpse of possibility for our present struggle. Our world today is far from the cosmopolitan vision the free trade coalition had in mind. Theirs was a vision of a world united in peace in a federation of democratic states (if not a world state), with no barriers to the movement of goods and free, enterprising human beings, the baleful presence of oppression, inequality, and inherited privilege long forgotten.

Yet the coalition saw a string of important victories. The Anti-Corn Law League succeeded in abolishing the Corn Laws in England. Women did secure the franchise. Democracy did expand to the working poor. And supranational institutions did take root throughout the world, with the United Nations and the European Union garnering the greatest fanfare, but various regional trading blocs and “neoliberal” entities like the IMF and World Bank shouldn't be forgotten. Needless to say, none of these organizations is without sin.

Some have warned of the vulnerability created by the leftist tendency to connect every political issue to every other social cause and demand unanimity on the whole “everything bagel.” To fight climate change we need a Green New Deal that must be intersectional and antiracist, and that implies Palestinian liberation, which means abolishing capitalism, etc. There’s some truth to this criticism. How could there not be?

But we can also be too timid, too insular in our campaigns. The cosmopolitan coalition worked because its constituents fit together organically, even magnetically. It would have been a mistake to jealously fixate on free trade, but ignore the single tax; or to protest imperialism and war, but neglect the mercantilist landed interests; or to create supranational entities without opening their borders.

In each case, the fight is against a powerful rentier class dominating politics to exclude others from their unearned privileges. Free trade removes the ability for politically well-connected capitalists and companies to seek (or pay for) carve-outs from tariffs. The land value tax extends to all the gifts of Gaia instead of allowing landowners to reap their riches without lifting a finger. Today we might include wealth taxes for rentier billionaires alongside the LVT. The extension of the democratic franchise to women, the unpropertied, and racial and ethnic minorities in the 20th century cracked open the unjust privilege of representation of rich men for rich men. This struggle continues as the political right continually seeks to exclude disfavored minorities from political representation. Open borders would extend access to wealthy labor markets and well-functioning political institutions (they seemed to function well once upon a time, anyway) from the lucky few born in rich democracies to all the people of the world. A YIMBY triumph would abolish homeowner feudalism and liberate the most productive and innovative cities for the people. And a feminist revolution in political economy would end the unearned rents of male supremacy.

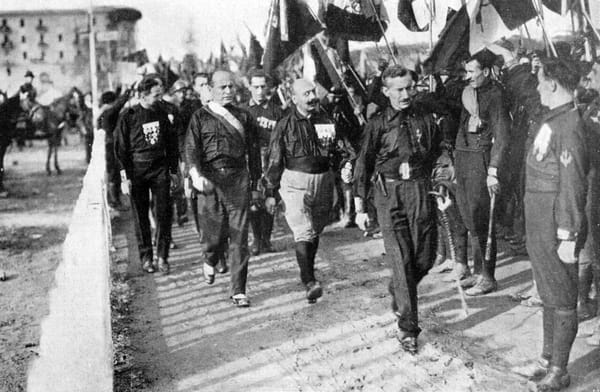

The ascendance of global fascism and its catastrophic, cascading consequences for human freedom and welfare create a political opportunity for proudly championing cosmopolitan values. The horror of Trump’s mass deportation, outsourced concentration camps, and the lawlessness of ICE kidnapping assaults on American cities may shift public opinion about immigrants in a liberal direction as it shifted during the first Trump administration. The chaos and inevitable inflation of Trump’s tariffs are reminding a goldfish-memory nation of the merits of free trade. The smash-and-grab corruption of an unaccountable and brain-poisoned tech oligarchy is opening minds to liberal socialist ideas. Vladimir Putin’s imperial aggression and Trump’s threats against erstwhile allies are already steeling liberal democratic nerves and inspiring coordinated response. The loss of abortion rights makes feminism all too relevant again, not just for women, but for everyone with an interest in sexual freedom and bodily autonomy.

There is synergy here if we are brave enough to see it, not an “everything bagel,” but a centripetal solidarity against a ruling class clutching their ill-gotten rents and hoarding power. Free trade isn’t just the stodgy old purview of Rockefeller Republicans; it rekindles the vision of an open world of friendly peoples and nations. The triumph of liberal democracy is the only path to peace. We don’t want to invade our neighbors; we want to trade with them, and not just goods, but culture, the burdens of mutual defense, and obligations to common causes like combatting climate change and global plutocracy. An open door to goods, services, and culture is simpatico with open frontiers for all freedom seekers. Democracy demands open borders, and the shining city on a hill is a tariff against tyranny.

The fascist worldview is one of domination of powerful white supremacist patriarchs over everyone else, ruthlessly enforcing its traditionalist religious values on the bodies of nonbelievers, dissenters, women, racial minorities, the disabled, and gender and sexual minorities. The feminists thus belong with the free traders, and leave the TERFs with the tariffs. The oligarchs have joined the warmongering imperialists, so let the socialists join hands with the liberals.