The End of (Teaching) History

A popular saying, often used when discussing the uncertainties of the past, is that “history is written by winners.” The implication is that the powerful create our narratives of the past, and the point of view of the various “losers” in history is unknowable. This truism is not, however, particularly true. In the Western canon, the “father of history” was Thucydides, an Athenian whose work The History of the Peloponnesian War details the origins and course of the war which ultimately led to the humbling and subjugation of his city. Thucydides himself is all too aware of the ways in which the past, even in his day, was rarely investigated with rigor, writing that “The way that most men deal with traditions, even traditions of their own country, is to receive them all alike as they are delivered, without applying any critical test whatever.” His introduction to the work reads like a Hippocratic Oath for historians:

with reference to the narrative of events, far from permitting myself to derive it from the first source that came to hand, I did not even trust my own impressions, but it rests partly on what I saw myself, partly on what others saw for me, the accuracy of the report being always tried by the most severe and detailed tests possible. My conclusions have cost me some labour from the want of coincidence between accounts of the same occurrences by different eye-witnesses, arising sometimes from imperfect memory, sometimes from undue partiality for one side or the other. The absence of romance in my history will, I fear, detract somewhat from its interest; but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content. In fine, I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.

The ideal of the unbiased historian tirelessly seeking out the one objectively true narrative has indeed struggled in modernity, as more emphasis is placed on the inclusion of multiple perspectives and exploration of how the past was experienced by individuals. But the central principle—that historians are creating or at least presenting knowledge about what happened by interrogating multiple perspectives, not weaving a romantic tale of the past—has long persisted, as has the belief that such a pursuit requires inquiry and constant critical re-evaluation of one’s views. This has of course been challenged, repeatedly. Perhaps the most famous example of Classical times is The Aeneid—an epic poem written by Virgil but commissioned by the Roman emperor Augustus specifically to create a noble origin story of the Roman people, entirely independent of any kind of historical inquiry. These two approaches to discussing the past—as an earnest quest for accurate understanding and as a tapestry on which to weave narratives that further one’s agenda—have both been vigorously pursued by those following in the wake of Thucydides and Virgil.

However, for all their rhetorical defense of rationalism and objective truth in the face of “postmodernism,” many conservatives in the United States seem to come down hard on the side of Augustus, that the proper way to discuss the past is not through history but a sort of national hagiography. A real effort is underway to actually cripple any efforts at accurate education, particularly in history. And unlike their social justice opponents, whom they warn as dangerously “canceling” free thought, the Right actually has the power of the state behind it.

A backlash to uncomfortable narratives

Though the tendency to sanitize history is timeless, much of the current push seems to come from The 1619 Project, a history/journalism initiative launched by Nikole Hannah-Jones in the New York Times 400 years after the date in its title. The project is aimed at re-centering the American narrative around the experience and impact of enslaved Black people and has stirred up a far more ferocious debate than is typical for popular history. Much of the criticism directed at the project is valid or at least valuable, in the sense that challenging conclusions or asking probing questions of a theory is the way in which historiography progresses. The debate has shined a light on important questions, including vexing ones like the extent to which slavery contributed to American prosperity and the degree to which the institution shaped our view of race compared to being shaped by contemporary racist beliefs. Another current within the criticism, however, is far more dangerous: the tendency in some quarters to insist that not only was the project factually inaccurate, it needed to be shut down since it presented a clear and present danger to the American education system.

The movement to revert to a more comfortable version of US history picked up steam in years following the publication of The 1619 Project. Parents and activists expressed concern over the idea that something called Critical Race Theory was infiltrating school systems, teaching white students to be ashamed of themselves and their history. It is entirely possible that some white students were made uncomfortable by the discussions of slavery, genocides against indigenous people, or other topics, and perhaps some teachers lacked adequate nuance in teaching these topics. But it is far more likely that this discomfort is at least partially because students are far more used to receiving the “traditions of their own country…without applying any critical test whatever.” It’s never pleasant being wrong—so students and their parents who grew up idolizing Thomas Jefferson can be expected to be indignant in seeing some of that façade stripped away. The sensation is all the more painful if on some level they—despite their genuine belief in colorblindness—find it easier to identify with Jefferson than with the people he enslaved.

One productive response by white students to this discomfort is to grapple with their own privilege, to think about ways in which it has or has not persisted in history. Another healthy response is to identify less strongly with a particular heritage—the less important whiteness is to one’s identity, the less likely one is to be offended or ashamed of the actions of historical figures who happen to be white. But, for many white parents and voters, the more attractive alternative was to shut down the teaching of any history that made them uncomfortable.

Legislating historical truth

The largest example in terms of scale is Texas, which in June of last year passed HB 3979. In addition to prohibiting the teaching of The 1619 Project by name, the bill stipulates that a teacher cannot ”require or make part of a course” several open historical questions, including that “meritocracy or traits such as a hard work ethic are racist…or were created by members of a particular race to oppress members of another race” or that “the advent of slavery in the territory that is now the United States constituted the true founding of the United States; or with respect to their relationship to American values, slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States.”

Admittedly, these are somewhat uncomfortable questions, and I would love for the version of history taught in Texas to be true. Indeed, a historian could reasonably argue that, for example, the ideal of meritocracy is a Renaissance belief that pre-dates American slavery. But the description of a meritocracy, applied to a society with such strong racial stratification, does imply the inferiority of Black people—and so regardless of whether it was created to enforce racial subjugation, it has had a role. That’s where historical debate and discussion occur—the tension between these positions. Entirely closing off one possibility slices off an entire wing of potential positions, lowering the quality of education in order to burnish a particular view of national history.

The question of “authentic founding principles” goes even further. First, it makes a major and likely unjustified assumption: that the United States has authentic founding principles. This is the realm of mythology, or perhaps Platonic idealism, not history. The US is not a college or corporation founded by an individual or small cohort with a unified vision. It was a society wrested from its larger parent by rebellion, a rebellion which involved tens of thousands of individuals governed by hundreds of politicians. These leaders varied tremendously in their views on nearly everything, including slavery and racism. The documents they created reveal these differences: the Declaration of Independence, while insisting on the equality of all men, refers to indigenous people as Savages; the Constitution grants judicial rights supposedly to all people but then explicitly endorses fugitive slave laws; many founders wrote eloquently about the nation of immigrants being created but the Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted immigrant citizenship to free white men.

So what constitutes an authentic founding principle when the same country and indeed the same individuals differed so much on questions of race and equality? In reality different people have used the question for their own ends. Abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass famously disagreed on whether the constitution was a contract that bound the nation to slavery (Garrison’s position) or a high minded statement of principles which, if taken seriously, made slavery impossible (Douglass’s take, well articulated in his response to the Dredd Scott dcecision). Coming to a definitive conclusion is a lofty goal, even for a professional historian, and certainly out of reach for a high school classroom. What a history class can teach, however, is the existence of varying stances on the same question. It can expose students to the process of discovering and analyzing differing stances. But the state of Texas, clearly uninterested in history, has taken it upon itself to define those authentic principles and censure anyone who might do the actual work of history within a history classroom and cast doubt the received traditions of the country.

Texas is hardly alone; Florida demands that schools “may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” Indiana has attracted attention for going even further—not only including the same language about meritocracy as Texas, but also requiring that schools set up committees, which are required to include a 60% majority of non-district employees with the power to make any curricular materials usable only on an “opt in” or “opt out” basis, ensuring that the history (and other subjects) taught are filtered not just through state standards but also whatever idiosyncratic historical views are held by the parents and surrounding community.

What’s at stake when we stop teaching history?

Of course this is just one back and forth in what is likely to be an extensive battle over how children are taught and whether they are taught history or mythology regarding the foundation of the country and its subsequent development. Debates about these fundamental questions are of course nothing new—American historiography on topics like slavery and the Civil War has gone through several stages of orthodoxy and revisionism, and The 1619 Project is only the latest example. But in taking the issue to legislatures, the political right is pulling the rug out from historical discussion, setting out the conclusions students are allowed to reach ahead of doing the work, choosing an epic narrative commissioned by the politically powerful over the hard work of historical investigation.

What are the consequences of such a choice? Some, ironically conservatives more than anyone, would argue that the truth is its own value, that treating the past simply as canvas on which to paint a comforting narrative is in itself an intellectual sin. By contrast, Matt Bruenig argues that there really aren’t any – that history class doesn’t matter much and most students are too checked out of it for the minutiae to make much difference. But the stakes are higher than that. In an era where all manner of information is easy to obtain but institutional trust is already low, giving young people unreliable or obviously sanitized historical instruction will likely make them more susceptible to misinformation about both the past and the present, as it destroys their ability to trust expert authority. Failing to expose students to the complexities of real history also robs students of the skills gained in wading through primary and secondary sources to gain a more nuanced understanding of an issue – precise skills that are growing more important in today’s media environment. And perhaps the deepest loss is in what we as a society can learn from the past. History is not always written by winners, perhaps because losers have the most to learn from the true exploration of the past. Thucydides wrote his History at least partially to explain and learn from the defeat of his own city. When narratives about the past are constrained by the need to protect the sensibilities of the socially and politically powerful, such honest self-reflection is impossible.

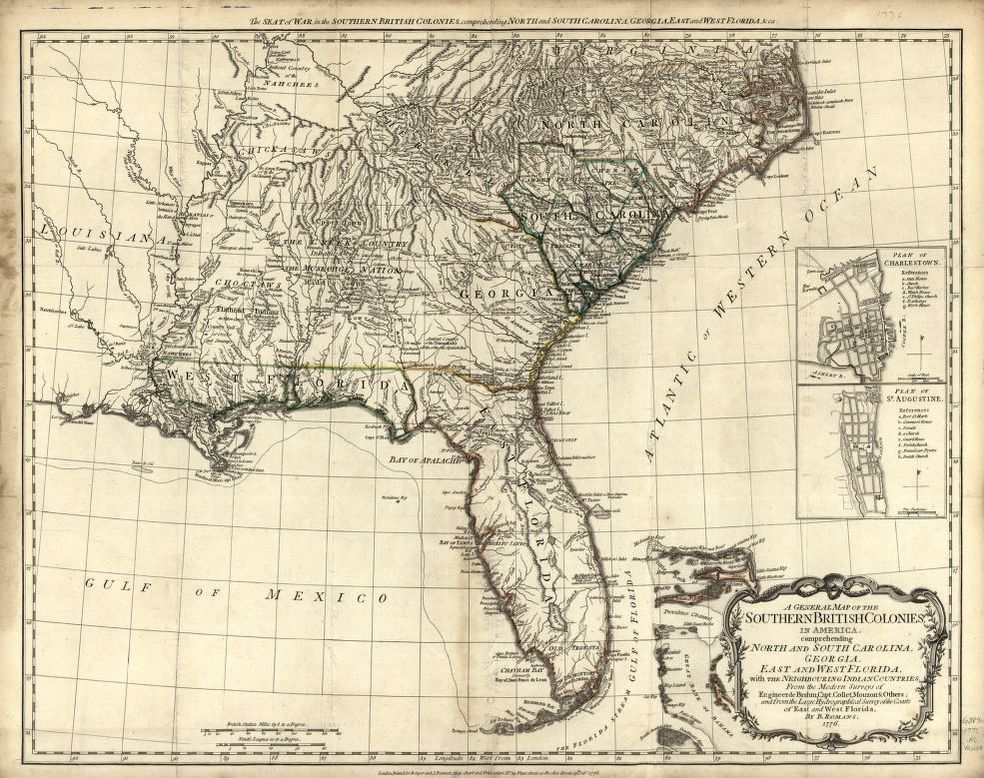

Featured Image is A general map of the southern British Colonies in America