The History of Successful Liberal Reform

When elites feared the system would fall apart entirely, they accepted reform.

The federal government is collapsing, and all of it is the act of one man. Whole departments and agencies have or are in the process of being shuttered by his agents. The ability to provide services like Social Security and Medicare is under threat for the first time in American history. Tens of thousands of federal employees have already been laid off by his whims. Elon Musk could do all of this because he is supported by the President. But this unique arrangement would not have taken place without the support he granted to Trump to secure his election. Since Trump would have most likely gone to prison if not for his victory, that means Musk ensured that Trump remained a free man. But he had his own reasons for aligning with the president. Musk’s position means he can steer billions of dollars in government contracts to his companies. Government policy is thus at the whims of a man who seems to be in the pursuit of boosting his own profits. One billionaire controls the levers to all of our collective fates.

In Congress, Republicans are busy assembling a favor-laden boondoggle of a budget that, in accordance with their president’s wishes, have literally titled the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. While there are no publicly available polls on the bill so far, its leading provisions, extending tax cuts for the wealthy and big business, and substantial cuts to Medicare, receive 19% and 17% support from the public, respectively. The legislation will also blow a $5 trillion hole in the federal deficit, which would mean higher interest rates and increased inflation. That might be worthwhile if the Big Beautiful Bill generates higher economic growth, but the nonpartisan Joint Committee for Taxation estimated it would provide 0.03%. All while the bill will likely increase poverty through cutting Medicaid and food stamps.

Many Americans sense that something has gone wrong, very wrong. Republicans in safe seats are going to town halls and watching their constituents turn against them, for the most part over DOGE. There is anger at the people hijacking our democracy. That was what gave Trump his initial appeal in 2016, even as he unleashed a tide of hate and vitriol that is still flowing today. But now he is a lame duck beholden to the billionaires. He has nothing left to promise but vengeance. That won him a plurality of the popular vote, but it did not win him a mandate. And so the system will continue working as intended until a new movement comes up to unite people behind the common desire for change.

It is easy for someone who believes in liberal democracy to feel despondent. The dominance of the billionaire class seems irreversible given how they possess so much control over our daily lives. And now their chosen candidate has taken the White House. But we have been here before.

To understand how America might escape from the clutches of oligarchy, it is worth reaching back through history, to see how the people have pushed back against the elites to achieve reform. They happened in Britain in the 1830s and America in the 1930s, struggles against the forces of reaction that ultimately resulted in the redistribution of power away from the oligarchy and towards the people. They were successful because they capitalized on fears within the ruling class that the system might fall apart and take them down with it. As a result, they chose to accept reform to maintain their position. The anger is there. The question is when it will reach the point that the political class is scared enough to do something about it.

The Reform Act of 1832

Britain has had a Parliament since the 1300s. What it did not have was a representative legislature. The House of Lords in the 1820s was composed mostly of wealthy landowners who could strike down any and all legislation that went against their ancient prerogatives that came up from the House of Commons. Fortunately, that did not happen very often, since the Commons was nearly as unrepresentative.

The boundaries had been drawn in the Middle Ages and as such had not kept pace with population changes over the centuries. There were no national voter eligibility requirements, and the rules varied wildly across the districts, for the most part dependent on holding some amount of property. The vast majority of people, tenant farmers and laborers who made up most of the British population, did not meet the property requirements to vote and as such had no voice within the political process. The shopkeepers and artisans who lived in burgeoning industrial towns like Manchester and Birmingham did not have representation at all, even if they would meet the property requirements elsewhere.

Parliament also possessed a number of districts known as 'rotten boroughs.' Since 1% of the population owned nearly 60% of the land, and since the constituency boundaries were essentially arbitrary, many wealthy landowners could control seats by having a few dozen of their tenants vote for a chosen candidate. Of the 267 seats in England and Wales, 36% (87) were effectively controlled by a single or multiple aristocratic patrons, while another 101 were under “some influence” from a patron. One constituency, Old Sarum, was a ruined castle on a hill voted on by eleven people, all of whom lived elsewhere. The seat could be bought and sold for the highest bidder to whomever wanted two MPs to vote at their behest. Among its owners were the wealthy Pitt family, who sent no less than eight members (including Prime Minister Pitt, the Elder) to Westminster.

The push for reform began after 1815, when the British economy began to sink into recession. Poor harvests caused by low temperatures led to a food shortage, and with it rampant unemployment. The same year, Parliament passed the Corn Laws, placing a tariff on all imports of grain. This was good for wealthy landowners who produced grain, but less so for the urban masses who now had to face higher bread prices. The people of Britain concluded that the current government was the cause of their misfortune, which was all too inevitable given that it was effectively unrepresentative of the population. Across the country, mass meetings were held demanding parliamentary reform, to give some semblance of rationality to a legislature that had barely changed since the Middle Ages.

On August 19, 1819, a crowd of people gathered in St. Peter’s Field in Manchester to demand changes to the country’s electoral system. Protests like that one had appeared in towns across England throughout the past few years, including several in Manchester itself. This one, however, got tens of thousands of people in attendance. Local officials ordered a volunteer cavalry force to arrest one of the leaders, and on their way got stuck in their crowd. Thinking they were under attack, the 15th Hussar Regiment charged into the crowd on horseback, wounding hundreds of people and killing 18 people. Given that the Hussars had previously fought in the Battle of Waterloo, a local newspaper dubbed what had happened the “Peterloo Massacre.”

The Peterloo Massacre did not result in any immediate changes other than the passage of the Six Acts through Parliament, which were intended to prevent potentially revolutionary activity. The majority in the Commons during those years were the aristocratic Tories, who were devoted to maintaining the privileges of the British aristocracy and uninterested in reform. Through most of the 1820s, it seemed that the Prime Minister, the Earl of Liverpool, could maintain power with little to no pushback from the unrepresented masses as long as he held the loyalties of Parliament.

Then, in early 1827, Liverpool suffered a stroke and stepped down. He was succeeded in the premiership by two short-lived Tories, none of whom were able to command the loyalties of a deeply divided party. The King appointed the Duke of Wellington, the hero of the Napoleonic Wars. In January 1830, the Birmingham Political Union was founded to advocate for political reform. Soon afterwards, multiple reform bills were proposed in Parliament, but none were able to capture anything close to a majority in Parliament.

Then, France fell into revolution.

On July 26, 1830, the government of arch-conservative Charles X promulgated the July Ordinances, intended to reinforce his grip on power. The next day, barricades began to go up in Paris in open opposition to the King’s decree. By July 29, the revolutionaries had taken control of the city and established a Provisional Government. Within days, Charles X was forced to abdicate and the crown passed to the more liberal Louis-Philippe, who vowed to rule as a constitutional monarch.

The July Revolution, as it was known, galvanized the forces of reform. Whig and Radical candidates in the general election that was taking place from the end of July to September linked their candidacy to the events happening in France. While its impact was somewhat muted because the news did not reach more rural constituencies, the Tories lost between thirty to fifty seats. Another hundred MPs refused to commit to supporting the government.

When Parliament reassembled in the fall, fears of revolution had become widespread. However, Wellington remained opposed to any kind of parliamentary reform to prevent such an occurrence. In a debate in the House of Lords, he expressed his belief that reform would not put the country in “a state to overcome the evils likely to result from the late disturbances in France.” In private, he thought he could even benefit politically. Soon, it became all too clear that the British government’s resistance to any kind of reform could very well cost them their power.

The first clear sign that a revolution might occur came with the Swing Riots, which began in August 1830. They were caused by angry farm laborers who feared increasing agricultural mechanization, along with a bad harvest in the 1828-1829 season. By early November, thousands of incidents had occurred, with warehouses on fire and threshing machines destroyed. It is unlikely that the rioters were influenced by the events in France or by a popular desire for parliamentary reform. What is true, however, is that members of Parliament who represented the areas of England most affected by the Swing Riots feared that it meant revolution.

At the same time, the people of London grew increasingly hostile to the government. The city had already been sympathetic to what happened in France, with public demonstrations in support of the revolution. The press demanded reform, arguing that the British people would no longer submit to their unrepresentative Parliament. In this atmosphere, Wellington began preparing for King William IV’s dinner at the London Guildhall, customarily scheduled for November 9. After being warned of potential trouble that might accompany the dinner and hearing that there were not nearly enough police and soldiers to protect those in attendance, the Prime Minister decided to cancel it altogether.

The cancellation of King’s visit made the collapse of Wellington’s government inevitable. Mobs began to roam the streets openly opposing the government and demanding reform. Soldiers were assigned to guard key locations like the Mint and the Tower of London, but this only made the crowds angrier. On November 11, the Times was supporting reform, and by the 15th, the Lord Mayor and the city council approved a petition calling for reform.

That day, Parliament was debating a routine financial matter, proposing a committee on the Civil List that granted the King an annual grant of money. The motion was promptly defeated by the opposition by a vote of 204-233. This effectively signaled that Wellington no longer had the votes to remain in power. He resigned the very next day. Among those who voted against the government were 34 Tories from Kent who were nevertheless concerned that rioters might move against their own holdings. Wellington himself later recognized that his government would not have collapsed had the July Revolution not occurred and made the populace demand reform.

To replace the departing Prime Minister, William called on the Whigs, the more liberal party, and their leader Earl Grey to form a government. Grey recognized that reform was necessary to ensure the continuation of the British parliamentary system, declaring that the “principle of my reform is, to prevent the necessity for revolution.” In early 1831, Lord John Russell, one of his principal allies, introduced a comprehensive parliamentary reform bill on the floor of the House of Commons. By a one-vote margin, the bill actually managed to pass the Commons on March 22, something unthinkable just a year earlier. Notably, Grey even managed to get 41 Tory MPs to support his legislation. However, this victory was short-lived when Parliament voted for an amendment that would not reduce the number of MPs representing England and Wales, which the Whigs opposed. Knowing he needed a bigger parliamentary majority, Grey called for the dissolution of Parliament and an election to take place.

The ensuing election, which ran from April 28 to June 1, returned an overwhelming Whig majority with a gain of 174 seats. It was clearly defined by the cause of reform, given that Parliament received 3000 petitions on the topic (most of which were in favor.) The Tories were all but reduced to seats controlled by local patrons, indicating that they lacked virtually any support from the British voting public. Key to the Whig victory was the presence of the Swing Riots, which increased their voting share by about 14%, nearly the difference between their percentages in 1830 and 1831. In other words, if not for the riots and the fear they invoked among local landowners, the Whigs would not have won their resounding majority.

Now with the support he needed to push through reform, Earl Grey submitted the bill to a second reading on July 6. This time, it passed by a resounding majority. Now in the committee stage, the Tories were able to submit amendments, but once the process was over the bill was approved by the full Commons and sent to the House of Lords. On October 8, they voted down the bill after a close vote, even with many Tory peers abstaining. The Lords had rejected the will of the people, and now they were to see a renewed swelling of popular fury.

As early as the night after the vote took place in the House of Lords, riots took place across the country. In Derby, multiple people were killed in street fighting, In Nottingham, the house of the Duke of Newcastle, a particularly vehement opponent of the bill, was burned to the ground. Bristol saw the destruction of dozens of buildings, including the bishop’s palace, and twelve people killed, nearly a hundred wounded, and more than a hundred taken into custody. On November 5, instead of burning Guy Fawkes’ effigy, protesters burned the effigies of the bishops who voted down the bill in the House of Lords. Now, moderate Tory peers felt compelled to begin negotiating with the government to find a compromise that could win a majority.

In December, Grey introduced a third reform bill, which passed its reading in the House of Commons by the largest margin yet. After its approval, the bill was presented to the House of Lords on March 26, 1832. After it narrowly passed its first reading, the bill now went to the committee process. However, because many of the majority votes were proxy votes that could not go into committee, the bill’s passage remained up in the air. After Grey and his cabinet resolved not to allow for the postponement of the elimination of the rotten boroughs, the bill was voted down in committee on May 7.

Now Earl Grey had to consider unleashing the threat needed to force the House of Lords into line: asking the King to add enough pro-Reform peers that the bill would pass. If not, Grey would tender his resignation. On May 9, William sent a letter refusing to expand the House of Lords and accepting Grey’s resignation. The same day, he asked the Duke of Wellington to take the premiership, although the Whigs would retain power until the Duke had formed his government. The immediate blowback was substantial, with more mass meetings and talk of civil war and even deposing the king.

The first step towards forming the new government would be in gaining the support of Robert Peel, the leader of the Tories in the House of Commons, who Wellington wanted as Prime Minister. It became clear that Wellington had to achieve some limited reform measure, but Peel refused to join, knowing that if his government openly opposed reform it might bring about the revolution. Meanwhile, the Whigs decided that, even if the Tories were able to get something passed in the House of Lords, they would vote en masse against the bill in the House of Commons, which in turn might bring down the government.

Even as both parties made their political calculations, the members of the Radical movement decided on a new tactic that might push out Wellington. They organized a bank run, by enlisting as many people as possible to withdraw their money from the Bank of England and hoard it. The Radicals hoped that this would result in a general financial panic and ensure that the Duke would be forced to step down lest the entire economy collapse on his watch. Soon, posters around the country proclaimed the slogan “To Stop The Duke, Go For Gold.” Within days, more than a quarter of the Bank of England’s gold reserves had been withdrawn.

On May 14, Parliament assembled, assuming that the Tory administration had fallen into place. Instead, after the City of London presented a petition that the House not vote on a budget unless the Reform Bill passed, a debate took place over whether Wellington’s government would at all consider reform. Then, Peel announced that he felt he would not be able to take on the position. The next day, Wellington recognized that he would not be able to serve as Prime Minister. The king sent a message to Earl Grey asking that he return to power and that he modify the bill to gain Tory support. In turn, Grey reiterated his desire for the King to issue the threat for new peers.

Over the next three days, the King maintained his refusal to add peers. In the streets, more public meetings were held, and while the bank run had ended, the Radicals now outright threatened revolution. There was now talk of barricades like those had been erected during the revolution in France. Finally, on the 18th, William gave way and declared that, if there were further obstacles to the passage of the bill, he would allow Earl Grey to submit a list of new peers. Threat in hand, Grey could now see the passage of his measure. On June 4, a half-empty House of Lords passed the bill on its third reading. Three days later, the King granted royal assent, and with it the Reform Act of 1832 was finally law.

The impact of the Reform Act itself was modest. Many of the old rotten boroughs were, at long last, removed, and other constituencies with populations between 2000 and 4000 lost one of their MPs. In turn, towns like Birmingham and Manchester which had been the earliest hotbeds for Reformist energies were now granted representation in Parliament. In all, the electorate increased in size by nearly 50%, and for the first time a uniform system of voter registration was instituted with consistent wealth requirements. The Whigs certainly benefited, as they were rewarded for their efforts in the general election of 1832 with 441 seats and a 67% share of the vote.

The Reform Act did not enact universal suffrage. What it did do was write into law the principle that Parliament should at least represent the people of Britain, rather than a small clique of landed aristocrats. The liberal triumphs of the following decades: reforming the Poor Laws, regulating labor, and, most notably, the end of the Corn Laws in 1846, were not possible without Reform. The latter bill was achieved by Prime Minister Robert Peel, who had been a staunch opponent of the Reform Act but more than a decade later decided on repeal to prevent a further crisis. And by 1865, Lord Russell, the man who had introduced the first Reform Act in 1831, had ascended to the premiership and proposed a second bill intended to further expand the franchise. While the legislation failed and Russell’s government collapsed, his successor, the Conservative Benjamin Disraeli passed it into law.

The Reform Bill’s arduous journey through Parliament made clear that reform was only possible under the constant threat of revolution. This was true during the Swing Riots and the collapse of Wellington’s government, the violence that followed the bill’s first rejection in the House of Lords, and finally the bank run and threats from the Radicals that followed Grey’s resignation. Left to their own devices the aristocrats who made up the key players of the drama from 1830 to 1832 would not have felt compelled to sacrifice their medieval privileges and provide the middle classes with some measure of power. But fearing that they would meet the same fate as the rulers of France, they acceded to their demands. Grey passed reform knowing that it would “prevent the necessity of revolution,” and as a result there was no revolution in Britain.

The New Deal

Much unlike Britain, which to this day maintains the anachronistic trappings of a monarch and nobility, America was founded on more explicitly egalitarian principles. These principles have clearly been ignored time and time again, but they form an important component of our national identity. So it is a great irony that, just as the fight to end slavery had ended, a far more pervasive threat to equality was emerging. That was the rising gulf between richer and poor, which slowly increased over the early 1800s and, by 1870, reached a high plateau. The Gilded Age had begun.

The fortunes of the Gilded Age were made by the explosive technological growth that characterized the late 19th and early 20th century. America had gone from reliance on kerosene lamps and horse-drawn carriages to lightbulbs and railroads. These innovations brought with them sustained growth in productivity, but did not improve the wages of American workers at the same rate. Most people remained solidly below the poverty line. The men they worked for, however, lived lavish lifestyles with vast mansions, elaborate social entertainments, and expensive vacations abroad. Sure, some of them committed their resources to acts of charity, but this was not nearly enough to improve the lives of most Americans.

The instrument that this small group of men used to achieve their vast fortunes was the trust. Organized to get around laws regulating corporations in more than one state, they were soon used to form monopolies on the supply of certain goods, often through anticompetitive practices. The pioneer in this regard was John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which grew from a small refiner in Cleveland to a massive vertically integrated corporation that controlled all aspects of the petroleum extraction process. Standard Oil muscled competitors out of existence to dominate the market, and by the 1890s they produced 90% of the nation’s oil output. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was intended to regulate this behavior, but Standard Oil reorganized its corporate structure and grew wealthier and wealthier by the day.

Through the first decades of the 1900s, a new movement emerged that sought to call attention to the inequalities of the time. These were the Progressives, and they soon became a prominent faction in both political parties. However, while some of their goals like the direct election of senators and the first income tax were adopted, for the most part they were stymied by a staunchly conservative Congress. The political class of that era had no interest in reforming the system that had given rise to the so-called ‘robber barons,’ given how many benefitted from their largesse. In 1896, Rockefeller gave substantial contributions to William McKinley to ensure that his opponent, the progressive William Jennings Bryan, would not take the White House.

And indeed, why should America need reform given the booming economy? This was the dawn of the new Fordist mode of production, in which products were manufactured on an assembly line and, as such, could be made faster and more cheaply than before. While the robber barons of the 1880s and 1890s had mostly retired at this point, they had left behind massive corporations. The namesake of this new economy was Henry Ford, who leveraged cutting-edge industrial design to churn out millions of identical Model T’s, nearly single-handedly turning America into a nation of drivers.

But most of the corporate titans of that era were not big because they were particularly innovative, but because they had been formed through mergers and acquisitions to create monopolies. The largest corporation of the era was U.S. Steel, created from the union of the Carnegie Steel Company and Rockefeller’s own mining interests as financed by J.P Morgan to create a behemoth that dominated the steel industry. It was followed by AT&T, which had similarly risen to dominance by acquiring hundreds of local telephone companies to the point that it controlled most local and long-term telephone service in the United States. The federal government had broken up Standard Oil (although Rockefeller remained the wealthiest American), but it was unable to take on U.S. Steel and AT&T, and as a result both only got bigger over time.

Through the 1920s, year after year, GDP continued to rise. The stock market grew year after year, spurring further consumer confidence. The Democrats did not help themselves by running a series of uninspiring candidates who barely represented an alternative to the Republicans. In the election of 1928, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover won in a landslide over Governor Al Smith of New York, even breaking into the Solid South for the first time since Reconstruction. A permanent Republican majority seemed foreordained as long as the system did not falter.

But this economic order was built on foundations as shaky as ever. Workers had not shared in the rising economy, as productivity growth outstripped wage growth. The richest 1%, meanwhile, controlled nearly half of the wealth, even if this had gone down thanks to the deflation of World War I. Farmers in particular were hard-hit by deflated prices, and before 1929 they were already effectively in a recession. This could be elided as long as the economy continued to grow. But what if it should start to decline?

Beginning in October 1929, the economy began to reach the brink of collapse.

The stock prices that characterized the 1920s were not the beginning of a “permanently high plateau,” in the words of one economist but a massive speculative bubble that was massively overleveraged. Over the course of 1929, there were clear signs of an economic slowdown, but stocks continued to rise. Soon, however, the floor fell out. After an early dip that the market recovered from, overleveraged investors dumped their holdings on October 28, and before long the Dow had lost nearly a quarter of its value. Over the next three years, it would lose 90% of its value.

Most Americans, then, would have been scarcely affected by what was happening on Wall Street. After all, they did not invest in the stock market. What it did do, however, was signal the beginning of a steady decline in consumer and business confidence in the economy. Unemployment began to tick up, while GDP declined. In Congress, the Republicans pushed their usual policy prescription: more tariffs. The resulting Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act drove tariffs nearly to their highest levels ever achieved, and imports and exports soon collapsed. At the same time, measures that could have helped matters, like an end to the gold standard, were not pursued (which other countries had done to lower the severity of their depressions.)

In any case, what made the Great Depression so great in America was not just the decline in unemployment or collapse in trade. It was the banking crisis. In late 1930, hundreds of banks, many of them small, unregulated rural banks where poor farmers kept their savings, began to fail in short order. In December, the Bank of the United States, the fourth-largest in New York, collapsed after a bank run on its Bronx location. The next year, thousands more banks closed their doors. Since there was no federal deposit insurance and the Federal Reserve at the time was weak and decentralized, there was no substantial governmental response. As a result, millions of Americans lost their savings. The unemployment rate began to skyrocket, and by 1932 nearly a quarter of the working-age population was out of a job.

To say that President Hoover did nothing to prevent the Depression would be an exaggeration. That said, his efforts, grounded in his belief in laissez-faire economics, were lackluster at best. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which passed while Republicans still held control of Congress, was intended to support domestic agriculture and manufacturing, but instead drove down their ability to sell abroad. In November 1930, the Republicans lost the Senate and managed a one-seat majority in the House. Hoover then decided that stabilizing the European economy could help matters, and negotiated a moratorium on German war debts. However, this did not produce the desired effect, as Europe entered its own downturn. By December 1931, when Congress returned to session, the Democrats had won enough special elections that they claimed a majority in the House.

Now facing an economic crisis greater than any of the Panics that had characterized the last half-century, and with it his impending re-election campaign, Hoover had to take action. However, he had no intention of reforming the system that had caused the Depression in the first place. The primary effort by the administration was the establishment of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation in January 1932, which was authorized to hand out loans to state and local governments and banks. However, it was both limited in funding and in its ability to make the kind of risky loans that might stimulate the economy. Hoover did also authorize some limited public works projects, but this came too late to make an impact on his electoral prospects.

The lackluster political response to the Depression resulted in the formation of the Bonus Army in mid-1932. Veterans of the First World War had been granted certificates for their service which were redeemable in 1945, but on the onset of the crisis they began to demand an immediate payout. Congress allowed them to increase the amount of money they could receive in the form of loans on its value, but this did not satisfy the veterans and they began to surge into Washington, D.C. as the Bonus Army. Even if the organization was motivated by a narrowly political end, it was initially organized by members of the Communist Party, who saw in it revolutionary potential (they were eventually thrown out once the Army reached D.C.)

By June, Congress was considering a bill to pay out the bonuses. The House narrowly passed the legislation, but the Senate subsequently voted it down on June 17. At that point, the veterans abandoned their camp in Anacostia to take up residence in abandoned government buildings. A stalemate remained in place for a month, while Hoover decided to wait out the Bonus Army. When they did not leave as expected, in part because many had no home to return to, on July 28 Hoover took action. After police could not clear out the buildings, he sent in the army under Douglas MacArthur. First, they cleared out the buildings with tear gas, with a few dozen veterans wounded and more than a hundred captured. Then the Army crossed the river and cleared the Anacostia camp, driving the veterans and their families out.

Both Hoover and MacArthur believed that what they had done prevented a socialist revolution, with MacArthur claiming the nation was “one week before a revolution.” However, the American people did not see what Hoover had done as staving off revolution. They just wanted jobs. As Hoover waited out the Bonus Army, the Democrats convened in Chicago to nominate their candidate, not far from the venue where they nominated William Jennings Bryan in 1896. Much like Bryan, their candidate would be dedicated to taking up the task of achieving progressive reform. This time, however, Franklin D. Roosevelt would be far more successful.

In contrast to his fifth cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, whose campaign twenty years earlier was marked by a bold progressive agenda, the ‘Square Deal,” Roosevelt was far more circumspect, with broader claims about his ‘New Deal’ agenda. (They did, however, share a penchant for calling their political programmes ‘deals.’) He criticized radicalism on both sides, calling instead for “a workable program of reconstruction” with agricultural relief and public works. He also called for a balanced budget, implying some limits to his willingness to spend money. On the whole, this platform did not provide any meaningful reform to provide a more equitable distribution of wealth in America. Some of this was certainly hesitation on Roosevelt’s part to avoid alienating any segment of the electorate. At the same time, he did not feel any pressure to provide a more radical agenda.

In any case, such was Hoover’s unpopularity that Roosevelt needed to do nothing more than offer a clear alternative to the incumbent to win a majority. Instead, he set out to gain a true mandate. He campaigned extensively, through areas that had traditionally never voted for Democrats, and reached millions of Americans through the radio airwaves. The result was a landslide. No Democrat since before the Civil War had won a majority of the electoral and popular vote simultaneously, but Roosevelt achieved both in dominant fashion. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, and most of New England went to Hoover. Every other state voted Democratic. With this landslide victory, Roosevelt also won the House and Senate majorities needed to enact his programs into law.

The New Deal should be best characterized in two stages, the First and Second New Deal. The First New Deal was focused for the most part on immediate relief without much of the reform-minded elements that characterized the Second New Deal. Early on, in his famous Hundred Days, Roosevelt focused on stopping the banking crisis that had kicked off the Depression in the first place. He instituted a bank holiday, along with deposit insurance to ensure that deposits would not be wiped out as they had in the early days of the Depression. He also ended the gold standard once for all, although at the time this was an emergency measure to inject more cash into the economy. This was later followed by banking reform through the Securities Act and Glass-Steagall Act, which were both intended to crack down on the sort of shady financial transactions that had led to the crash in the first place.

The First New Deal did also contain provisions intended to provide relief for the working classes who had given Roosevelt such substantial margins in the election, and would form the basis of his New Deal Coalition for decades to come. This included the so-called ‘alphabet soup’ agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), with the former two providing temporary low-skill employment while the latter handed out direct cash assistance. Roosevelt also made an effort to alleviate the agricultural crisis through the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), effectively paying farmers not to plant crops to reduce the overproduction that had caused their depression in the first place.

The most far-reaching legislation of this period was the National Industrial Recovery Act. The law included many different components, but the most important (and controversial) element was the establishment of the National Recovery Administration. The NRA attempted to impose something resembling corporatism, by establishing trade associations across industries and establishing codes of conduct with which they had to comply. Initially, the NRA was quite effective in improving working standards through higher minimum wages and shorter working hours. However, there were limits to the government’s ability to enforce the codes, while price-fixing and anti-competitive practices became all too common and in turn increased costs for consumers. More crucially, the NRA did not reduce unemployment. After the NRA’s director, Gen. Hugh Johnson, began drinking heavily and distributing fascist tracts, Roosevelt fired him, leaving the organization without effective leadership and preceding its demise the next year.

By 1934, the New Deal was beginning to put the economy back on stronger footing. Ending the gold standard injected much-needed liquidity into the economy. GDP growth resumed after four straight years of decreasing. The unemployment rate, which had risen every year from 1929 to 1933, finally started to decline. The Dow Jones Index, which had reached its lowest levels since the 1910s in June 1932, had managed to double that level two years later. But that year, alternatives to the left showed the popularity of reform rather than just the program of reconstruction the Roosevelt administration had enacted. These included the strike wave of 1934, candidacy of Upton Sinclair in California, and Huey Long’s Share Our Wealth program, all of which represented alternatives to the New Deal and which gained surprising popularity.

The labor movement was in the 1920s floundering after decades of consistent and harsh opposition from industry. Violent suppression of strikes and a concerted effort from big businesses to paint unions as Communist-aligned resulted in the unionized workforce being nearly cut in half from 1920 to 1929. The proliferation of yellow-dog contracts, where workers were compelled to state that they would not join a union, ensured that large segments of the workforce would be closed to unionization.

Then, the Depression struck, and in doing so reignited the labor movement to achieve its greatest triumphs. The American Federation of Labor, which was founded to represent craft unions for skilled workers, had been hobbled by cautious leadership unwilling to expand membership into the larger unskilled working masses, and risk further violence. Instead, leaders like John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers took matters into their own hands. Through 1933, Lewis capitalized on Roosevelt’s working class popularity to expand the union’s membership, which by year’s end would be half a million strong.

The next year, major strikes broke out across the country, demanding union recognition, and this time they achieved marked successes. In April, an AFL affiliate in Toledo, Ohio, struck against the Electric Auto-Lite Company, and although multiple people died in the so-called ‘Battle of Toledo,’ the strikers earned union recognition by early June. May saw both the successful Minneapolis Teamsters’ Strike, in which a local of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters achieved union recognition even after fatalities among both the strikers and police, and the West Coast Longshore Strike. There, the International Longshoremen’s Association demanded a union hiring hall, and when employers refused the longshoremen walked out of every port in California. After the police tried to open the port of San Francisco on July 5 and fired into the crowd, resulting in two deaths, a general strike was called in solidarity for four days. By October, the union had achieved its demands and cemented its power in the state.

By year’s end, 750,000 workers had joined the AFL or another industrial union. The labor movement had become a force to be reckoned with.

Even as the longshore strike raged on in California, Upton Sinclair began preparing to run for Governor of California. Sinclair, who was then known as a pioneering muckraker of novels like The Jungle, turned his attention to politics after the Depression hit, realizing there was an opportunity for his brand of leftism. In 1933, he was sufficiently impressed by Roosevelt to change his partisan affiliation from Socialist to Democrat. He began mobilizing the EPIC movement, dedicated to, as the name spelled out, ending poverty in California. His program called for a public works scheme where the unemployed would be hired to work at new factory and farm cooperatives. Sinclair amassed a broad following, with dozens of EPIC clubs appearing throughout California. From this, he began running for the Democratic nomination.

President Roosevelt had won California in 1932, but the state Democratic Party itself was still weak and divided. For the 1934 elections, it was hijacked by the EPIC movement. Not only was Sinclair nominated by a margin greater than that of the Republican nominee, suggesting he might win the general election outright, but dozens of EPIC-endorsed candidates were nominated to the state legislature in his wake. At that point, the Republicans realized that they were in trouble. The Hollywood producers, led by the arch-conservative Louis B. Mayer, funded an extensive propaganda campaign intended to smear Sinclair as a radical Communist. Together with a progressive candidate splitting the left-of-center vote, Sinclair was one of the few Democrats to go down to defeat in California.

However, other governors were elected espousing their own regional brand of leftist politics. In Minnesota, Gov. Floyd Olson’s Farmer-Labor Party had enacted a far-reaching populist agenda while nearly driving the state’s Democratic Party out of existence. In Wisconsin, brothers Phillip and Robert La Follette abandoned the Republican Party to form a new Progressive Party, which swiftly came to dominate the state’s politics. The most powerful of these men, and the only one who posed a direct challenge to the president himself, was Sen. Huey Long of Louisiana.

Both Long and Roosevelt were charismatic, but where Roosevelt appealed to voters with his patrician demeanor, Long was a true demagogue, rising to power with his invective against the corrupt government and Standard Oil. After losing the 1924 gubernatorial election, he won in 1928 by mobilizing a working-class coalition and calling for new programs to improve the welfare of the state’s citizens. After taking office, he swiftly consolidated power into his own hands. Long’s opponents impeached him in 1929 when he attempted to tax oil production, but the ‘Kingfish’ bribed the state senate to prevent a trial before retaliating against them by firing their relatives. As governor, he passed a massive public works program, building new roads, schools, and the tallest state capitol in the United States in an effort to increase jobs.

In early 1932, Long left Louisiana and took up his seat in the Senate, where he made a name for himself opposing the policies of the Hoover administration and against wealth inequality. Initially, he supported Roosevelt, and helped in his nomination, but by 1933 he was disheartened with the New Deal (especially NIRA) and proposed his own alternative. This was the Share Our Wealth program, which would cap private fortunes and redistribute the money among the rest of the population. By 1935, the Share Our Wealth clubs had 7,500,000 members, and Long began to be viewed as a potential candidate for President. There was soon talk that he might align himself with Father Charles Coughlin, the infamous ‘Radio Priest,’ and Dr. Francis Townsend, who proposed a system of old-age pensions, on a third-party ticket that could swing the White House away from Roosevelt.

All of this radical energy might have overshadowed Roosevelt and left him vulnerable to a challenge on the left. Instead, he co-opted and folded those forces into his political program. Many of the goals advocated for by Sinclair, the labor movement, and even Huey Long became core components of what became the Second New Deal.

After the Democrats received a vote of confidence from the American people by actually gaining seats in the 1934 midterms, Roosevelt began to work on what might be the most transformative legislative push in American history. First came the National Labor Relations Act, guaranteeing the rights of unions to organize and banning unfair labor practices. This law ensured that labor unions would remain inside the Democratic tent, an alliance which lasts to the present day. This was followed by the Social Security Act, providing old-age pensions along with unemployment insurance and assistance for children in low-income families. While this was not as generous as Townsend’s proposal, it nevertheless made his movement more or less obsolete.

Still, the administration did not lose sight of their goal of reducing unemployment. In May, the National Recovery Administration was ruled to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. At that point, however, the administration redoubled its focus on pumping money into the economy through public works. In April, Congress voted $5 billion for work relief, and the next month Roosevelt founded the Works Progress Administration. This would go to hiring millions of workers, who would be employed building up the nation’s infrastructure. Together with the Public Works Administration, which focused on larger-scale projects like dams and bridges, these began to drive down unemployment and get the economy on track. Among those who benefited were Black people, who were allowed to take jobs even as they were segregated.

The most pivotal New Deal legislation in breaking up the concentration of wealth were also, unsurprisingly, those which faced the stiffest legislation. While Roosevelt did not propose wealth limits like Huey Long, he did propose a tax on the wealthiest incomes of 75% along with other taxes. The Revenue Act of 1935 only managed to pass once some of the more punitive features, like an inheritance tax, were removed. These high rates would remain intact until the 1980s. This was followed by the even more dramatic fight over the successful passage of the Public Utility Holding Company Act, which regulated electric company monopolies that had long been resistant to antitrust lawsuits. The federal government had stared down the wealthy and corporations, and won.

When campaigning for re-election in 1936, Roosevelt justified the New Deal not only on its own merits but as an inoculation against radical ideologies. In a speech in Syracuse that September, the president explained that he opposed Communism because it was “a manifestation of the social unrest which always comes with widespread economic maladjustment.” That unrest was made possible by the Depression: “In the spring of 1933 we faced a crisis… made to order for all those who would overthrow our form of government.” But rather than turn to violent suppression, which took place during past crises like Haymarket, the Pullman Strike, and the Bonus Army, Roosevelt turned to reform: “We were against revolution. Therefore, we waged war against those conditions which make revolutions—against the inequalities and resentments which breed them… Americans were made to realize that wrongs could and would be set right within their institutions.’

That last point is important. Despite the claims of his critics, Roosevelt was nothing like Huey Long, a proud believer in the ends justifying the means and a man who came as close as anyone in American history to establishing a personal dictatorship in his home state. He recognized the need for social change, but (at least in his first two terms, prior to Japanese internment) not at the expense of liberal values like free expression and democratic governance. When he laid out his Four Freedoms in 1941, he included freedom of speech and worship alongside freedom from want. By showing that the United States could reform itself without descending into revolution, he could prove that it was possible to achieve change within a democratic system. Accepting his renomination at the DNC in 1936, Roosevelt said that “in other lands, there are some people, who… sold their heritage of freedom for the illusion of a living. They have yielded their democracy… We are fighting to save a great and precious form of government for ourselves and for the world.”

Roosevelt went on to win the election of 1936 with an even larger majority than before, even while the Socialist and Communist Parties both won a smaller share of the electorate than they had in 1932. And why would they not vote for the New Deal when this was the greatest advance for left-wing politics in American history?

After the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, establishing a minimum wage, ban on child labor, and a forty-hour workweek with time and a half overtime pay, Roosevelt had achieved virtually the entire progressive agenda in just five years. And although income inequality remained high through the Depression, after World War II returned the United States to full employment the share of wealth held by the richest declined to 30-35%, the lowest level in decades. If not for the crisis that American capitalism faced in the 1930s, all of this would not have been possible. By reforming the system, Roosevelt ensured that leftist candidates like Long and his successors would be unable to gain power, or would be utterly co-opted by his party as with the labor movement. Thanks to the reforms of the Depression, the next thirty years would be an uninterrupted period of economic growth where the lower and middle classes benefited.

At present

The United States today faces a crisis similar to both Britain before the Reform Act and our own country before the New Deal. The richest have an even larger share of wealth then during the Gilded Age, and this continues to rise year after year. With it comes greater power, and now they wield untrammeled power over our democracy. The actions of Elon Musk and his DOGE are only the crude hammer by which the functions of government established during the New Deal and prior are systematically unravelled, removing any limits on the power of the rich and corporations.

Given how close the 2024 presidential election was, a clear factor in Trump’s victory was his support from plutocrats. He spent $288 million through his America PAC and other groups. While the Democrats raised more money overall, Musk chose to focus his efforts on legally dubious schemes, like a million-dollar lottery to get people to register to vote and payments for people who referred a vote registration form to their friends. Together with Timothy B. Mellon and Miriam Adelson, the three billionaires collectively provided a third of Trump’s war chest. All of these were maximized by loopholes in campaign finance laws, through which Trump could use his money more effectively than his opponent and narrowly win the election.

On a broader level, Musk has been effectively using his control of the media to dominate the national agenda and steer it towards his ideas. When he first bought Twitter (now X) in 2022, no one had much of an idea of what the platform under his control might look like. Now, more than two years in, its shape has become clear: a megaphone through which he can promote his views. Look no further than the trending page to see the issues of the day that Musk wants the users of X with which they might engage. Sure, left-wing topics do pop up, particularly around Gaza, but this serves his purposes too by amplifying an issue which divides his opponents. This is reminiscent of none other than Henry Ford, a fellow plutocrat automaker who tried a similar strategy through his use of the Dearborn Independent to promote antisemitism. However, where Ford was forced to back down through the legal system, Musk now has the government at his back to ensure he will face no accountability whatsoever.

Trump and Musk may be the culmination of corporate power retaking control of government, but their takeover would not have been possible if not for decades of neoliberalism gutting the foundations of the system established by the New Deal. Years of tax cuts, the decline of unions, and deregulation has removed virtually any constraints on corporations and the wealthy to do whatever they want. One need look no further than the fact that, from 1978 to 2023, executive compensation increased a thousandfold while worker pay increased by only 24%. Over this same period, productivity growth came to be 2.7 times higher than wage growth, even while union density declined, meaning that fewer workers were able to negotiate better compensation. The politicians who instituted the policy changes that made this possible promised that it would all lead to higher growth, yet after the Internet-fueled boom of the 90s it has been markedly lower than the heavily regulated and unionized 1950s.

The new neoliberal order has bred widespread discontent among Americans, especially younger people who recognize a country that is not able to face the challenges they will have to struggle with in the future. Polls clearly show that people do not have trust in their elected officials, and regardless of whether this is true or not it clearly shows a sense of frustration with America today.

No recent story illustrates this more vividly than Luigi Mangione’s assassination of UnitedHealthCare CEO Brian Thompson, and the surprising public support he received. If Mangione had assassinated a CEO in any other industry (well, outside of oil and gas and Big Pharma, which have even lower favorables), the public response would have been very different. Such is the unpopularity of the American healthcare system that many people believed it justified murder. There is clearly majority support for government-run, single-payer healthcare. And yet, the Big Beautiful Bill Act’s Medicare provisions would mean that fewer people are able to access healthcare.

So what can be done? The likelihood of a popular revolution being threatening enough to overthrow the government through violent ends became more or less obsolete with the invention of the machine gun. Trump will probably push the economy into recession with his tariffs, but at worse this might result in 10% unemployment, certainly not the 25% reached during the height of the Depression. What else can spook the ruling classes into making change? It is at least possible that catastrophic climate change-caused disasters can bring about a Green New Deal, but if wildfires in the richest parts of Los Angeles cannot do it, who knows how bad things will have to get?

Part of the problem is that, while people are clearly angry, there is no ideological movement under which they are unified. After all, Donald Trump was elected thanks to the support of Rust Belt voters whose economic situation was threatened by the very same neoliberal ideology that his party has been consistently supporting for the last forty years. Mangione’s own politics seem more or less incomprehensible, a confused synthesis of Silicon Valley techno-utopianism and libertarianism. This ideology is popular among people in tech, but less so among normal people.

By contrast, both in 1830 and 1933, there was a clear ideological underpinning that united the movement pushing towards reform. In 1830, there was radical liberalism, as articulated by thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and James Mill, articulating the view that Parliament should be representative of the people in accordance with their rights. Meanwhile, what one might call the social liberalism of the New Deal emerged from criticisms of capitalism levied by thinkers like Thorsten Veblen and Louis Brandeis, along with the new economic approaches from economists like John Maynard Keynes. There was a new and original criticism that had been levied towards the ruling order which could be easily turned into policy.

By contrast, Luigi-ism does not have a political programme that can be put in place, save maybe the “break stuff, fix later” approach that Elon Musk tried and failed to implement in the federal government. So far, this has not been particularly well-received with voters. But where are the new ideas out of the left? During the 2024 election, Kamala Harris talked a lot about lofty values, but when it came down to policy her economic proposals came down to tax cuts and small expansions of existing programs. Meanwhile, Trump went big and bold with his tariff plans, sovereign wealth fund, and massive deportations. Even though most of these plans have not really been implemented, at least he had something to offer voters. Harris couldn’t even bring herself to support a public option like Biden had in 2020.

To revive the cause of reform, there needs to be a new kind of liberalism, one that speaks to the economic challenges and political realities of America today. New Deal politics are well and good, but they were crafted for a country where most people were either farmers or factory workers. Where is the liberalism that speaks to the needs of baristas, home health aides, and other service jobs that form the backbone of the American economy? What will excite people to vote en masse in the same way they did in the British elections of 1831 that returned a massive Liberal majority and our own elections of 1932 and 1936 which gave FDR the mandate to implement the New Deal?

But even if such a new direction becomes clear in the next few years, it may take a long time until the crisis comes around that will shake the system and make the ruling elites willing to accept reform. However, there is clearly a large number of people who want things to change. All it takes is a revolution in Paris or a stock market crash in New York that can force the system to fight for its very existence. Once they’re on the ropes, reform that seemed impossible only a few months is suddenly a political reality. The current administration may be making a lot of people feel dispirited with the state of American democracy. But the Tory government of the Duke of Wellington and the Hoover administration seemed unassailable too. Until one day, it’s all over. And a new era has dawned.

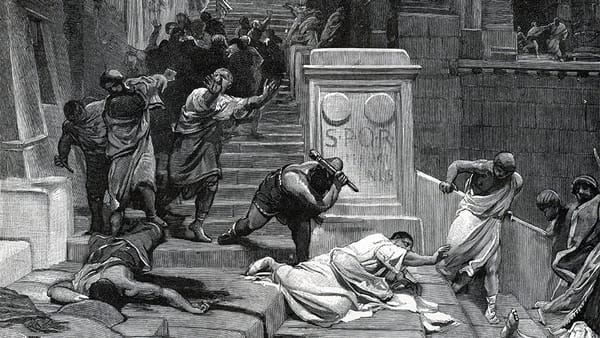

Featured image is The "System" That "Works So Well," by George Cruikshank