The Liberal Case for Public Power

When power is treated as a public good, it becomes cheaper, more reliable, and better positioned to meet the challenges of the future than privately held electrical utilities have ever demonstrated.

It was the Saturday before Christmas when the lights went out across San Francisco. Beginning around 1PM, homes and businesses across the Richmond, Sunset, and Tenderloin districts along with chunks of downtown and the Mission found themselves plunged into darkness as a fire in a PG&E power substation disrupted electricity transmission across the city. Many businesses, who had prepared for a busy holiday shopping weekend, were forced to prematurely close when the loss of power disabled electricity-dependent devices like credit card readers, point of sale systems, and Internet routers. Traffic snarled across nearly a third of the city, a situation made worse when dozens of Waymo automated taxis froze up at intersections all over the affected neighborhoods and fell into safety mode, transforming the vehicles into impromptu barriers. It took nearly two days, in some places, for power to be restored despite PG&E’s promise of a complete return to normal by the night of the 20th.

In the wake of this disaster, State Senator and Democratic Congressional candidate Scott Wiener revived his previous advocacy for municipal power two days after the outage by promising legislation that would empower San Francisco and other California municipalities to break away from PG&E. His main competitor for Nancy Pelosi’s seat, Saikat Chakrabarti, staked a similar position in a December 21st statement which concluded with, “No more talk. Time to change. Kick PG&E out of SF.” The question of who owns our electricity and what that means has surged back into the local headlines, prompting many to ask if public ownership is indeed the answer.

The idea of public ownership of electricity may sound like a socialist’s dream but municipal and public power are as American as baseball and apple pie, with a track record of solid, affordable, and reliable performance. This is because, as history and recent events show, electricity is a commodity which is so essential for modern life that it works best when treated as infrastructure maintained for the common good instead of as a business opportunity. When power is treated as a public good, it becomes cheaper, more reliable, and better positioned to meet the challenges of the future than privately held electrical utilities have ever demonstrated. This case is made as much by the successes of public power in California and Nebraska and as it is by PG&E’s history of shortcomings, repeated crises, and disasters.

At its core, the case for public power rests on a phenomenon in economics known as natural monopolies. Natural monopolies are goods or services which are cheaper for a single operator to produce and distribute than if production is divided between multiple competing providers, with electricity being a commonly cited example. The reason why such monopolies exist is because they usually require significant, up-front investment to build the necessary production and distribution systems, benefit enormously from the falling costs associated with economies of scale, and as a consequence established players enjoy often insurmountable advantages over new competition.

For natural monopolies in electricity production, the money paid by consumers winds up being more like a tax paid to investor owned utilities (IOUs) than as money paid in a competitive market for goods and services. US electricity markets practically guarantee this, with most electricity providers operating in what are, in fact, noncompetitive markets where the local power company is the only game in town. For most Americans, the costs and risks of electrical utilities are carried by the ratepayers in captive markets while profits go to the investors. Public utilities, thanks to their non-profit structure, are not subject to investor demands but instead must prioritize the good of their consumers and, as a bonus, pay no taxes on their operations. These differences are the core of makes public power cheaper to operate than most IOUs. These factors show why publicly owned power is as old as IOUs with examples in surprising places.

One of the best representatives of the competitiveness, cost, and reliability of public power is the state of Nebraska, which currently boasts the third-lowest average electricity price in the country. Since 1970, 100% of Nebraska’s power has been provided by an array of public utilities like the Omaha Public Power Department (OPPD) and the Nebraska Public Power District (NPPD). Both utilities have also, since then, consistently offered low prices and high reliability. A 2025 study by the Texas Electricity Rankings found the NPPD’s retail prices were in the top 5.2% nationwide for affordability, making their cost to consumers 45% lower than the national average, and ranked number one for reliability in the United States. The OPPD, in their 2024 annual monitoring report, similarly outperformed the competition with residential retails coming in at 22.3% below the national average, commercial rates at 28% below the national average, and industrial rates at 20.9% below the national average. Nebraska’s grid has also adopted cheaper wind and solar power at a fairly respectable rate, increasing the amount of electricity generated by renewable means from 11% of the grid in 2015 to 36% as of 2024 with the goal of hitting net zero by 2050.

The same patterns of reduced costs and high reliability can also be found in PG&E’s own backyard at the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) and the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (LADWP). These utilities were products of the early 1900s when the cost of building electricity infrastructure for relatively spread out, more rural regions was greater than private investors were prepared to pay. Ever since, they have grown to keep up with the increasing demands of both major cities with the SMUD now providing electricity for approximately 669,512 customers and the LADWP responsible for serving the needs of 1.4 million LA residents along with providing power for municipal facilities and local businesses.

While neither is ranked among the cheapest in electricity nationwide, both have kept cost increases down in the face of post-COVID inflation while those of IOUs like PG&E, SoCal Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric have soared. Electricity costs in California, like the rest of the country, have been soaring with the average residential rate surging by 47% from 2019 to 2023 and the big three of California IOUs saw theirs surge between 48% and 67% in the same period. The main exceptions, as reported by Inside Climate News, were LADWP and SMUD whose rates consistently remained 50% lower than those reported by their privately-held competition. These prices, along with PG&E’s own disastrous history, which will be detailed later in this piece, are why Gavin Newsom once proposed a state takeover of PG&E in 2020, Ventura County supervisors to vote in favor of seceding from PG&E to set up a municipal power company, and San Francisco authorities proposed buying out PG&E’s grid in the city for $2.5 billion back in 2019, an offer which was refused.

If a future Congress wants to go further and put control of electricity in the hands of the public, they may find it more affordable than you might expect. The Edison Electric Institute’s data on investor-owned utilities in the United States estimates the total value of all IOUs at approximately $2.1 trillion, a total which is less than half of the $4.6 trillion given away by Trump’s 2018 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as tax cuts for billionaires that were made permanent by his Big Beautiful Bill. For that low price, Americans of all walks of life could enjoy a genuine decrease in the cost of living and doing business, and enjoy the economic stimulus of more money into millions of pockets. These savings could be further amplified as the growing pace of the green energy transition accelerates the falling price of renewable electricity. For publicly owned grids, these savings would be passed on to consumers instead of the local power monopoly, generating even more economic stimulus for all.

What lends further urgency to these discussions are where matters go beyond kitchen table economics and reach into matters of public safety, a place where PG&E has an at best dubious record. San Francisco’s power outage is the latest in a string of disasters caused by PG&E’s generally reactive approach to crisis management and grid modernization. As journalist Katherine Blunt shows in California Burning: The Fall of Pacific Gas and Electric – and What it Means for America’s Power Grid, PG&E has, in recent history, modernized and updated its grid more in reaction to serious disasters than as a product of forward-thinking planning. Most of these disasters were also products of PG&E’s drive to cut costs and maximize profit at every opportunity.

One brutal example was from 2010 when a gas pipeline in San Bruno exploded, killing eight people and destroying seventy homes. One dispatcher quoted in Blunt’s book remarked, “It’s easy to believe it’s a plane crash”. A subsequent National Transportation Safety Board investigation concluded the highly corroded, dangerous state of the natural gas pipe was due to PG&E’s own extended history of negligence, cost-cutting, and inadequate maintenance dating back to that particular pipeline's faulty installation in 1956. The same culture of constant budget cuts and head count optimization was found to be at fault in the 2018 Camp Fire which was, at the time, the deadliest wildfire in California history that consumed over 150,000 acres, destroyed the town of Paradise, and was caused by a neglected, nearly century old PG&E utility line. These are two of many similar examples of catastrophic neglect by PG&E which US District Judge William Alsup described in 2022, after PG&E completed five years of criminal probation received in 2016 for the San Bruno gas pipeline disaster, as a, “crime spree” and remained, “a continuing menace to California” following the “failure” to rehabilitate PG&E during this period.

Hopefully, this latest example of a PG&E-related electricity disaster becomes a turning point in the story of electricity in California and the United States. As past and present experience has shown, public power is cheaper and more reliable than the aptly-named IOUs and bad actors like PG&E have shown utility ownership is more than just a question of dollars, cents, and market efficiencies. If, no matter how you slice it, we are going to be paying taxes to someone for our electricity, wouldn’t it be better for those funds to go where they will do the most proven good, be handled responsibly, and reflect consumer needs over investor profits? If there’s one thing the story of PG&E and municipal options like SMUD, LADWP, and NPPD have consistently shown, it’s that public ownership may be the best model of ownership for electricity and other natural monopolies.

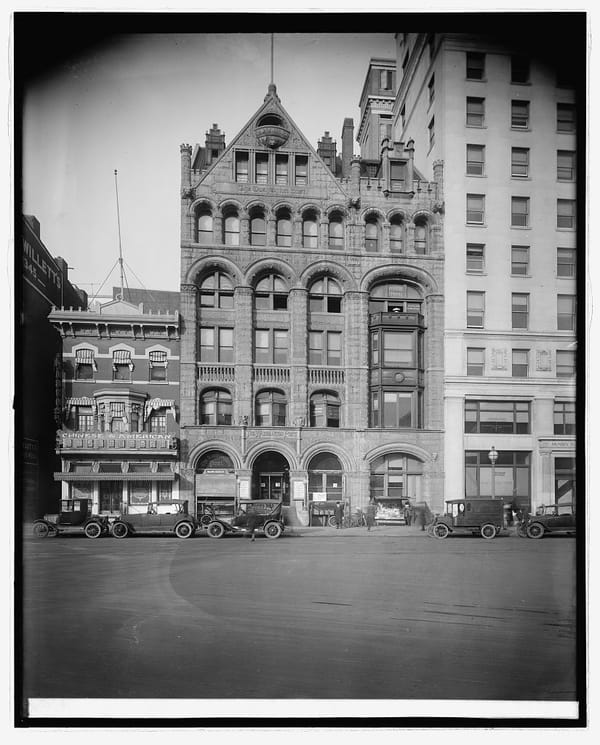

Featured image is Big Electrics, by arbyreed