The Most Childish Imperialism

How Trump is different from the old imperialists, and how the liberal world must respond.

To think of those stars that you see overhead at night, these vast worlds which we can never reach. I would annex the planets if I could; I often think of that.

-Cecil Rhodes

The United States will once again consider itself a growing nation, one that increases our wealth, expands our territory, builds our cities, raises our expectations and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons. And we will pursue our manifest destiny into the stars, launching American astronauts to plant the stars and stripes on the planet Mars.

-Donald Trump, Second Inaugural.

I.

This has been the most tumultuous year in international politics since 1989, and it is only May. It has become clear that the second Trump administration is breaking with the norms of US foreign policy that have held since 1945.

No one likes to live in unprecedented times. More historically minded writers have analogized these days to the last great age of imperialism between the middle Victorian period and the First World War. During this time, imperial powers like Britain and France had their final waves of expansionism, while emerging states like Japan, the USA, and Germany felt their legitimacy as nations, their destiny as powers, and their very survival depended upon a seat at the conquerors’ table. Above all, it was an era marked by the destruction of traditional societies across Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific, and its shameful legacy is still visible today.

The comparisons to today seem obvious. Trump’s contemporaries, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, both claim the legacy of dead empires. Putin describes the conquest of Ukraine as a sort of sacred necessity, invoking a history of a greater Russian nationalism stretching back to the Kyivan Rus. This is language that would be recognisable by any Tsarist nationalist of the late Romanov court. Xi and the CCP’s demands on Taiwan, as well as Tibet and the nine-dash-line in the South China Sea, are explicitly tied to their continuity with the Great Qing that ruled those regions, not any imagined Han nationalist state.

Trump also fits the model. He has called for the annexation and ethnic cleansing of Gaza, the seizure of Greenland, and re-claiming sovereignty over the Panama Canal zone. He demands the mineral wealth of Ukraine. He’s threatened to invade Canada—and given the abortive American invasions of Canada in the 1770s, 1812, and even later private attempts, that at least puts Trump’s threats in a tradition of empire hunger that predates the United States itself.

The open greed has reminded some of the most notorious imperialists of all. ‘Certainly Donald Trump’s foreign policy has a 19th-century feel to it,’ writes David McWilliams in The Irish Times. The column discusses how the Irish revolutionary Roger Casement was first radicalised by seeing the horrors in the Congo Free State. Those horrors are returning, writes McWilliams, and Trump’s foreign policy is ‘a version of imperialist resource plunder.’ The same comparison has been made by Paul Krugman. To him, Trump’s strategy in Ukraine ‘looks like the Belgian Congo in the late 19th century, a personal possession of King Leopold which he brutally exploited for its rubber and ivory.’

This is not a comparison to make lightly; millions were enslaved or slaughtered in Leopold II’s corporate hellhole. Even by the standards of the time, many Europeans and Americans saw the Congo Free State as evil, a corruption of what was otherwise seen as the noble project of empire.[1] The Congo Free State remains a byword for rapacity and brutality—so why not use it as a metaphor for a man as rapacious and brutal as Donald Trump?

The answer is not comforting. Trump and his government are not nineteenth century imperialists, because nineteenth century imperialism operated within a diplomatic system that allowed those empires to function. It was a system of racial supremacy and ingrained classism, but it was also a system that was designed to prevent conflicts between great powers. There were avenues for imperialists to signal to other states what they considered to be their national interests; there were diplomatic summits whose decrees were respected. There was, and this is crucial, an appeal to ideologies of European civilisation and capitalism that both justified the depredations of empire and theoretically limited them. It was a grotesque system, and no one should mourn its passing. But it was an international system that had buy-in from the great states of the period.

Nathan Goldwag’s ‘The Second Time As Farce: Imperialism in the 21st Century’ clearly perceives that Trumpist foreign policy is born out of a failure to understand the current global system. It desires to defend and expand American interests without having to pay attention to the meaningless liberal, feminine niceties of modern diplomacy.

I think that’s basically what all of MAGA foreign policy is, an attempt to redress grievances real and imagined by imposing a 19th century imperial framework on a world they don’t or won’t understand.

There is a misreading here though, and it’s the same problem with Krugman’s comparison.

The crisis of Trumpian foreign policy is not that it’s trying to escape a system it doesn’t understand and revert to nineteenth century imperialism. The crisis is that it is trying to revert to the nineteenth century imperial framework without understanding that, either.

II.

The nineteenth century empires were shaped by and governed within particular moral and intellectual frameworks. It is not that the great powers all shared the same philosophy of governing or of imperialism; the absolutist Tsarist creed of ‘Orthodoxy, Nationality, Autocracy’ was different from the French Third Republic’s ‘mission civilisatrice’, and both were different again from the bureaucratic-monarchist melange of nationalities that was Austria-Hungary. They all had complicated hierarchies of race, ethnicity, religion, class, and gender, but these hierarchies never manifested the same way in any two empires and often varied widely within the bounds of those empires. One thing that was shared, though, was a willingness to exclude states and societies that did not operate according to the norms and niceties of European courts. Clothing, language, and norms of sexuality and gender all became shibboleths of imperial modernity. When Meiji Japan sought to join this system, it immediately began to dress its politicians in top hats and frock coats. Their neighbours in Qing China kept traditional dress and haircuts, cementing bigoted western images of the archaic and alien Manchus. If you dressed as a respectable member of this system, you might be treated as a member of that system.

Compare two incidents of contempt for the leaders of small powers.

In 1881, King Kalākaua of Hawaii was hosted by Edward, Prince of Wales at a party in London. The King was eager to secure good relations with Great Britain, the only power that Hawaii might use as a plausible counterweight to the United States. He was dressed in the uniform and medals of a Victorian monarch, and was given the first dance with the Princess of Wales. The German Crown Prince complained that he had to cede precedence to Kalākaua, to which Edward replied that ‘either the brute is a king or else he is an ordinary black n——-, and if he is not a king, why is he here?’. The Hawaiian King got his dance.

A few weeks ago, we saw another leader from a small nation go to an imperial capital to fawn upon the rulers. This time, we saw Volodomyr Zelenskyy get publicly upbraided for his temerity in insisting on his country’s independence. He had not been sufficiently grateful, he did not appreciate the sacrifice of American dollars, and of course he had not worn a suit.

The comparison shouldn’t be overdrawn. Zelensky’s allies do not treat him with racist contempt, and Trump’s insults were shocking in part because the Ukrainian president has generally been treated as an international hero. Hawaii's attempt to secure independence through performative western modernity failed; when American businessmen overthrew Kalākaua’s successor a decade later, Britain did not protect the Hawaiians.

But the important point is this: if you were outside the framework of European ‘civilisation’, there was a narrow road to acceptance within it, however cruel and treacherous. Japan managed it, many colonised elites managed it, and Kalākaua was acknowledged as a King by the most powerful country in the world. What Trump and Vance demonstrated at their press conference was that you can be within their system, you can be a head of state and an ally of the United States and still be expelled just because the President dislikes you.

Put it another way: if Trump had been presented with Kalākaua, would he have seen a king, or something else?

Imperialist norms of courtesy ultimately just masked the underlying brutality. But we do not justify those norms by noting that their existence is a vital difference with the whimsical anarchy of Trump’s foreign policy. The nineteenth century was an age of famously cold-blooded political operators, Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck chief among them. Even that arch-manipulator, however, paid attention not just to what he considered Prussian and German national interests but also to how to create a narrative that justified the pursuit of those interests. In 1870 he manipulated France into declaring war on Prussia—and after winning that ‘defensive’ war he argued in vain to give France more generous terms than were eventually offered. He hosted diplomatic summits in 1878 and 1884, tying all the great powers to the new status quo. He was also the man of blood and iron, yes, but he could draw that blood with a scalpel.

Trump’s imperialism, on the other hand, is staggering in its clumsiness. He is not the successor of Bismarck, but to the man who fired him—Kaiser Wilhelm II. One of Wilhelm’s recent biographers, Miranda Carter, drew the parallel directly, dryly observing that ‘The Kaiser viewed other people in instrumental terms, was a compulsive liar, and seemed to have a limited understanding of cause and effect.’ Bismarck picked his battles carefully, dividing potential opponents and knowing when to make concessions at home and abroad. Wilhelm and his Chancellors casually insulted rival powers, alienating even those foreign statesmen like Britain’s Joseph Chamberlain who sincerely worked towards friendship with Germany.[2] We do not need to overdraw the parallels. The main lesson is that even lip-service to diplomacy smoothed Germany’s rise; once it was replaced with bluster, its situation deteriorated.

Consider Trump’s threats to Canada. There’s a long tradition of American designs on their northern neighbour, from the failed invasion of Quebec in 1775-1776, through the Fenian raids post Civil War, to the proposals after World War Two to incorporate Newfoundland into the United States. A more traditionalist imperialist president might have tried to lure away Alberta. Or, taking a longer view, they might double down not on tariffs but free trade, trying to integrate Canada ever closer into the American economy and bureaucratic regulations. There are, after all, institutions like the North American Leaders’ Summit that could be used to push for closer political ties. Across the Atlantic, the EU provides a vision of multinational integration that our hypothetically competent imperialist might steal to make US expansion sound more enticing. Failing all that, a standard imperialist—like Putin—would at least claim that American annexation was correcting a historical wrong, or completing the American revolution, or at the least was in response to some dastardly Canadian plot that was a suitable casus belli.

Donald Trump has not done these things. His threats are incoherent, if no less threatening for their incoherence. On 3 February he declared that under the current status quo the USA subsidizes Canada, that he will cut those subsidies off with his tariffs, that that means ‘Canada ceases to exist as a viable country’, and ‘therefore, Canada should become our cherished 51st state.’ In January he suggested Canadians would benefit from the American healthcare system, not something traditionally seen as one of the USA’s selling points. And earlier still, he suggested that he would invade Canada—to protect it from being invaded.

If Canada merged with the U.S., there would be no Tariffs, taxes would go way down, and they would be TOTALLY SECURE from the threat of the Russian and Chinese Ships that are constantly surrounding them. Together, what a great Nation it would be!!!

This is, frankly, stupid imperialism in this or any other age. There’s no attempt to sway Canadian or American public opinion. There’s no specific grievance to point to, no tangible Canadian sin. There’s no figleaf to hide behind, and no room for negotiation—Canada can give up everything, or suffer. And actually, Trump muses, if they do give up then he is happy to pay for them. ‘Now, if they're the 51st state, I don't mind doing it.’

This is profoundly destabilising, and it is also not how empires historically worked. A cynic would say that the 2024 status quo pro ante Trump of Canada-USA relations was more typical of nineteenth century imperialism than this current circus. The British Empire encompassed a quarter of the globe in 1900, but its informal reach stretched further still. Argentina, for example, was an ‘unofficial dominion’, whose economy relied on British export markets, whose ruling elite were educated and socialised in Britain, whose foreign policy was determined by the need to keep their patron’s favour. A British Prime Minister would not have threatened to the plant the Union Flag in Buenos Aires. A British Prime Minister would not have seen the need. In fact, in that same period British imperialists were discovering that they could not get Canada to impose tariffs on non-imperial goods, because already the US market was too valuable. In other words, even by the measure of imperialism Trump is attacking the ties that bind Canada and America together.

The closest Trump gets to the traditional mode of imperialism is when he talks about seizing Panama. That, at least, is standard revanchism– the USA held the territory, it built the canal, and, the narrative goes, only lost it because of weak leadership at home. In fact, not taking it back would be an act of weakness. Flimsy stuff—but typical. That is the sort of justification that can be used to support the annexation of Crimea or Taiwan in the modern day. But you might also find it in the years before World War One in demands for the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France or any other nationalist touchstone. Panama is also the only area of Trump’s imperial dreams with an actual constituency; there has always been a segment of the American right who see Jimmy Carter’s withdrawal from the Canal Zone as a disgrace to be wiped clean. But Greenland? Canada? Only cranks wanted them, but even cranks didn’t want Gaza. Trump has changed that. That’s another difference with the nineteenth century: Trump pursues imperialism before he creates imperialists.

The colonial empires ranged from autocracies to limited democracies, but all of them had particular colonial and expansionist lobbies and interest groups. That might be colonial charter corporations such as the New Zealand Company in Britain, or the timber and mining firms that helped drive Russian expansion into Manchuria. There were also missionary groups who wanted their churches expanded, existing settler colonies that pushed back their borders without permission from the home government, individual adventurers like the American freebooter William Walker who invaded Nicaragua in the 1850s. Because this was an age of expanding literacy and news media, these imperialist lobbies were visible not just within their own societies but also to other governments. This meant that it was not a surprise to Britain that parts of the French and German publics wanted territory that Britain controlled or might control; and because it was known, diplomatic accommodations could be reached (at the expense of whoever lived on the land in question.) This also meant that interests could be prioritised—Samoa was handed to Germany in 1899 to get a free hand for the UK in South Africa, for example. If nations understand each other's interests, deals can be made.

Not in 2025! Now the President announces some new imperialist scheme on the fly and suddenly supporters materialize after the fact. Ten years ago, Fox News was not debating the merits of annexing Canada and Greenland. Trump says that it’s a good idea, and annexationists appear. Even six months ago, right wing social media wasn’t talking about an American holding in Gaza. Now, we are treated to opinion pieces about every half-baked thought as every passing fantasy of conquest as if it’s actually a bold new idea.

Nineteenth century empires didn’t work that way. No halfway stable system of diplomacy has ever worked that way. Not even the notoriously destabilizing Kaiser Wilhelm II worked that way. We discussed Wilhelm’s similarities to Trump, but by the time the Kaiser was destabilising the international situation in the 1890s and 1900s there had been several decades of German nationalist groups who agitated for colonial expansionism. Groups like the German Colonial Society backed their eccentric Kaiser; they did not spring up out of his eccentricities.

The old imperial powers were hungry for other people’s land and resources, but one day’s ambitions looked like those of the day before. Their system collapsed in 1914, but if empires routinely changed their policies on a whim like the current administration does, World War One would have broken out much sooner.

III.

We have an administration that is pursuing all the worst parts of old imperialism, but without any sense of the guardrails that let it function.

To say ‘at least that system was a system’ is trite, and reminiscent of The Big Lebowski. ‘Say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism,’ a character remarks, ‘at least it’s an ethos.’ This is an essay about the powers within the system, but for the societies outside it it was an age of ruin and bloodshed. Krugman has compared Trump’s Ukraine policy to Leopold's Congo, but we are many dead bodies and severed hands from that being fair—for now.

There is another difference: Leopold hid his bodies.

The Congo Free State masqueraded as a humanitarian enterprise. It was bringing civilization, and hospitals, and churches, and schools. The ivory and rubber being extracted was just, Leopold assured the world, a way of keeping the colony on a sound financial footing. Besides, it brought commerce to the locals. It took decades to expose the horror: the slavery beneath the pretense of abolitionism, the greed beneath the charity, the slaughter beneath the smile.

Trump wouldn’t bother with the pretense.

Trump’s imperialists want to bring back an age where great powers can pursue their dreams of conquest. But they do not want to bring back the supposed morality that justified those conquests; even hypocrisy is too much of an effort. Nineteenth Century Imperialists believed they were spreading civilization; if anything, their ideological successors are in many ways the neoconservatives like the Project for a New American Century with its policy of ’military strength and moral clarity.’ The total moral and political failure of that ideology is its own subject, of course, but the neoconservatives genuinely did believe that they were building and rebuilding nations, for however little that is worth. Trumpism does not believe in nation-building; Trumpism does not really allow that other nations have any value or right to exist beyond acting as a market for American goods.

The Trump acolytes do not want to have to acknowledge the existence of small states, they do not even want to go to the effort of conjuring elaborate historical justifications for why they should do what they already want to do. They proclaim themselves deal makers, but they cannot make deals in the manner of the old diplomatic conferences since they will not clearly declare their own interests or admit that anyone else has legitimate interests. They do not want constraints of law, or customs, or niceties. They do not want to be constrained today by what they said yesterday or what they might say tomorrow.

For those of us outside the United States, we face a twofold challenge. The first is not to convince ourselves that the new Trump presidency can be treated as a normal state. During the first Trump administration, there was a tendency to believe that the President could be managed by the fabled ‘adults in the room’. It has become increasingly clear that that will not be the case in this term. The ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs were a turning point; it is not just that they were brutal or unfair, it is that they were profoundly stupid. Trump has revitalised the fortunes of flagging left-liberal governments in Canada and Australia. In both countries, right wing candidates found their march to electoral victory horribly interrupted by the actions and words of a man they had praised. In February, Australia’s opposition leader, the Liberal[3] Peter Dutton was confident enough to praise Trump as a ‘big thinker’ after the President called for the ethnic cleansing of Gaza. By an election debate in late April, Mr Dutton was refusing to say whether he trusted Trump and calling the treatment of Zelensky ‘a disgrace.’ Pierre Poilevre in Canada has fared even worse. Both Dutton and Poilievre went on to lose the national elections, and their own seats.

As Trump’s new term goes on, other countries must not sink back into complacency. Treasury Secretary Scott Besant appears to have won the latest battle for the President’s attention and got a temporary climb down on tariffs and the trade war, though god knows how out of date that sentence will be when you read it. There is already a sense that the bond markets have defeated the worst of the tariffs; that must not be allowed to firm into a belief Trump’s foreign policy will be tamed.

The second challenge will be to patch holes in the sinking ship that is the international order. The United States is the lynchpin of the multilateral system; even rivals like China must worry of what the consequences of a rogue United States might be. This is why the irrationality of Trump’s imperialism is so dangerous. If he was aggressively pursuing national interests or simply trying to extract as much wealth from the world as possible, then his actions might be anticipated, accounted for, or deferred. But as we have seen, there is no national interest to Trump except what has caught his attention; no foreign policy goals for his supporters except to outdo themselves in justifying his latest pronouncement. This is jackdaw imperialism. To not be American at this moment is to sigh in gratitude—and then worry that tomorrow your country might look shiny.

We must also play for time. There will be shameful and embarrassing moments as international heads of state stroke the president’s ego and sing the praises of American leadership that no longer leads. Will Rogers once said that ‘diplomacy is the art of saying “nice doggy” until you can find a rock.’ America is a very big doggy, and the rest of the world has very small rocks. We must carefully judge when to stand up to the bully, and when to distract him with parades and state visits.

Liberal democracies must build new links and fast. European democracy was sorely tested in the 2010s, with the far right making inroads on the back of first the Eurozone crisis and then mass resentment of Syrian refugees. The next decade might well be grimmer; Italy is already in the hands of the far right, and France and Germany have not beaten back the threat yet. To face them, and to face a far right American government—and to face Russia, and to face whatever crisis we don’t know about yet—there must be a move beyond technocracy and managerialism. Those have kept the EU intact; but to keep it free there will have to be a new spirit of European progressivism that has something to offer the angry young.

In Asia and the Pacific, the long term may be even grimmer still. The democracy that Trump has placed in most danger is his own, but Taiwan vies with Ukraine for the silver medal. There we see a liberal democracy under imminent threat of invasion, and its great protector is no longer reliable. Taiwan will be the next great test of international democracies. The other democracies of Asia have long planned for what happens if and when China tries to seize the island, but a contingency that has genuinely seemed unthinkable is what happens if China tries to seize the island and America just does not care? What do the other liberal democracies do in such a scenario? What damage would be done to their own free societies by their acquiescence?

New alliances must be built, and old ones reinvigorated. Defence spending must go up, and we must find new arsenals of democracy far from American shores. If they do not exist, we must build them—and fast. This will be horribly expensive, and we must do this at a time when we still face all the demands of aging publics, the climate crisis, creaking states, and the thousand crises any free society must always deal with. The public will not have confidence in this sort of muscular progressivism unless we can demonstrate positive changes in the day to day experience of the voter. To resist Trump—and to resist other empires without the aid of America—we cannot choose between guns and butter. We must find both. This is not an argument for militarism; it is a recognition that even if the democracies aim no higher than to protect themselves from the whims of empires, we must work together and spend enough on mutual protection to make our alliances credible.

Above all, though, we must never accept that the world Trump is building is normal or acceptable. If our democracies are to survive, then we cannot simply hope that we can muddle through until the fall of Trump and the Trump party. That fall may not happen soon, and even if it does the America that follows may well be too bruised to act on the international stage. It may not happen at all. We must be the bastions of our own democracy. A return to the world of empires would be grim enough, but Trump is threatening something worse; a world where the greatest empire changes course without reason or rhyme, where no agreement is binding because the rules and institutions that protect it no longer exist. If the world our democracies exist in is not stable, then our democracies cannot, in the long run, be stable.

[1] Today, whether the Congo Free State was meaningfully ‘worse’ than other imperial possessions is hotly contested. The point is that at the time even imperialist and racist Europeans thought it was distinctly evil.

[2] Alas, his son Neville would really outdo his father in the game of ‘failed diplomatic agreements with Germany.’

[3] A quick note for foreign readers: The Australian Conservative Party is the Liberal Party, the centre-left party is the Labor Party, the socialist party is the Green Party, and the Liberals stand as ‘Community Independents‘ with the funding of a climate-conscious multi-millionaire. The party of local regions is the National Party, which has its heartland in conservative blue states. The right wing is proud of passing gun control, and progressives are proud republicans. We don’t actually do this to confuse Americans, but it’s certainly part of the fun.

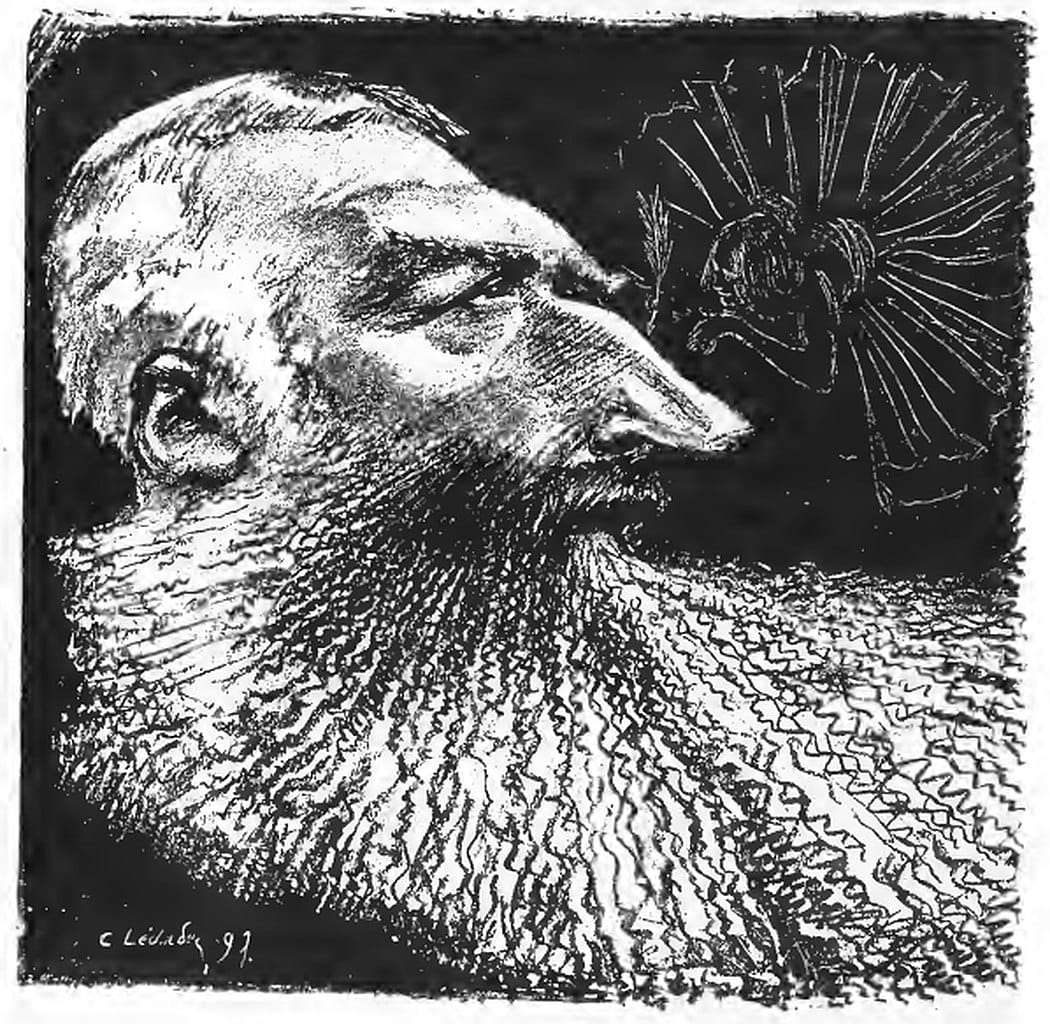

Featured image is Portrait Caricature Of King Leopold II of the Belgians, by Charles Lucien Léandre