The Politics of Humiliation

The politics of humiliation has moved to the center of the reactionary project under Trump II.

When I was in middle school I went through a rough patch socially. I was awkward, had hardly any friends, and was hence a target. I can recall one instance where, returning to the classroom after leaving to use the toilet, a group of boys my age (who were also out of class for some reason) found me and started following me, taunting me. Eventually—and I imagine with some emotion in my voice—I rounded on them "what did I ever do to you?"

This, to them, was hilarious. "What did I do to you?" they started repeating in a sing-song voice. Outnumbered, and with no obvious recourse, I had little option but to continue back, them following, continuing their parody of my outburst. It's a small moment. Nothing ever came of it, no material change was affected. Yet I can still taste the emotion of it. Anger. Powerlessness. Shame. A kind of self-blame and regret.

It's not a story I would share at parties or with friends. Even in circumstances where I might talk of grief, or failures, I would not talk of humiliation. Sharing it now, publicly, feels quite stressful—despite it being the most minor of incidents. I feel the need to add that things improved for me in high school, that I learnt how to play the social game better. That I had friends and girlfriends. To let you, the reader, know that as a grown man I would not tolerate treatment like that.

Why? Why my reticence, why do most of us not talk about such moments? They are, after all, the ones we struggle most to let go of. The answer is simple enough: one of the effects of humiliation is the destruction of status claims. As a result, being—or even recounting being—humiliated lowers our standing. We do not listen to humiliated persons. Frederick Douglass, recounting much more extreme instances, got to the heart of the matter with his usual clarity; "Human nature is so constituted that it cannot honor a helpless man, although it can pity him; and even that it cannot do long, if the signs of power do not arise."

Perhaps for this reason, even in writing that mixes the personal and political, humiliation has not been a major theme. We've frequently (and correctly) discussed the Trump movement in terms of cruelty. I want to argue that thinking in terms of the politics of humiliation adds something to this.

This may sound like a weird phrase. But humiliation, I've come to believe, is important not just interpersonally, but politically. So, I ask the reader to hear me out—to 'go with me' on this seemingly strange thesis—and consider what our political world and our political morality looks like when we start from the perspective of these personal, ugly—but seemingly irrelevant—acts.

What is humiliation?

When I say humiliation is an important political concept I tend to get two reactions: a blank stare and an instinctive click—"yes, absolutely, that makes total sense." For those in the former group, we might start by noting it does seem to fill a gap, does it not? Why is Trump so willing to cause massive harm with tariffs just to have world leaders say fawning things about him? Why was there so much glee in Elon Musk's firing of government workers? Why were Trump's victories greeted with an increase in yelling abuse at service workers, and why did the perpetrators so often reference Trump when doing so?

To those for whom humiliation as politics feels intuitive, let me try and add some structure—I'll start with a definition I've developed: Humiliation is the forced recognition of domination.

Consider: In 390 BC, Rome was attacked by Gauls and totally captured apart from the Capitoline Hill. According to Livy, the Romans agreed to ransom their city for 1,000 pounds of gold. While this was being weighed out, the Roman envoys complained that the counterweights being used were rigged in the Gaul's favour. In response, their chieftain Brennus took out his sword and threw it on top of the rigged weights. "Vae victis!" he declared, usually translated 'woe to the vanquished'. The Romans not only had to get even more gold, but they had also been utterly stripped of their dignity.

Brennus was, in this action, humiliating them. Yes, he got a bit more gold, but that wasn't the point. The point was to make it obvious and undeniable how powerless they were. Any relationship where one person has power over another like this—power that is unaccountable, that can be used arbitrarily, at a whim—has the potential for humiliation.

Philosophers call being at another's mercy like this 'domination' or being in a 'relation of domination'. Brennus was—at least in that moment—in a relation of domination with the Roman envoys. An absolute monarch is in a relation of domination to their subjects. Far from being an ancient relic, domination is alive and well in our world, in more or less subtle, and more or less obfuscated, ways. Employment At Will is, I would argue, a relation of domination. A racial caste system, even an implicit one, can be another. As are some of the consequences of inequality.

When we force people to recognise their own domination, their own powerlessness, we humiliate them. The 'forced' part is essential: humiliation is necessarily non-consensual. Imagine some affluent college frat boys, coming home from a night out, encounter a homeless man begging and decide to have some fun with him. They offer him $20, nothing to them, but everything to him. Ah but wait—he'll have to earn it. "Dance for me" they demand "act like a monkey". He's visibly shaken by the request, but they're serious. So, he does.

This isn't a hypothetical, but a real interaction—I encountered a video of it online some time ago. I won't link to it because I think it's despicable. This is humiliation. The difference in resources—and the homeless man's desperation—create a relation of domination between them and they are forcing him to recognise it. If, by contrast, a man with sufficient means to not be desperate, chose to work as a street performer for tips this would be a totally different story.

Humiliation is not 'merely' symbolic. It is an immoral act that has serious, long-lasting consequences. The effect of it is the destruction of our status claims. Even the most desperate among us try to present themselves with a certain amount of dignity. Humiliation removes that. It also isolates us from other people, makes us feel more alone, and leaves a deep and lasting anger.

Human parasitism

Our world is structured by relations of domination. Yet, for the most part, we pretend it's not. You work as an 'Employee at Will' in a labour market where a replacement can be found easily. Hence you can be fired at any time, your entire life turned upside down, maybe losing your home, or ability to continue with necessary medical care. Your boss can do this to you at a whim. But in many workplaces this isn't reflected in behaviour. Some bosses, and some work cultures, demand deference. But in many settings, the social norms are those of equality—supervisors are friendly, ask what you did on the weekend, perhaps even socialise a bit after work.

This goes for everything. Classical Marxism tells us there's an underlying structure of power relations in a society, and that we then create an obfuscatory 'superstructure' of ideas, norms, and behaviours to hide it. Unlike most liberals (and indeed many Marxists) I think there's a certain amount to be said for this. Our mental worlds assume a much greater respect for the dignity of persons than actually exists.

What makes humiliation so strange is it operates in the exact opposite direction to the one Marxism imagines. For the Marxist, the obfuscatory superstructure will be punctured from below: the working class will grasp 'objective reality' in a moment of 'class consciousness,' leading to liberatory change.

But humiliation always comes from a position of power. I say position rather than person as, given intersectionality, there may be cases where informal hierarchies 'pull' in different directions—for instance a working class man and an upperclass woman might attempt to humiliate each other in different ways. It is a behaviour concentrated in elites. In all cases it moves down the hierarchy.

It isn't however in the powerful's interests—they benefit from the obfuscatory superstructure; it makes that power less visible, more palatable. Humiliating others can also undermine the justificatory myths the elite rely on—that their position is justified by their intelligence or merit, for instance. Finally, because it makes people so angry, humiliation can spectacularly backfire. Caligula was apparently murdered by his own guards, so furious that he made them say humiliating phrases that they killed him without even planning who would be the successor. Even in less dramatic cases, elites humiliating those beneath them is destabilising. You create people who are angry and will hold onto that anger.

Yet humiliation is a behaviour we see in every system of domination. For instance, the most extreme such relation is slavery. In every known slave system, the degradation of enslaved persons is a central part of the institution. Again, we might ask, as Orlando Patterson does, why "the master so wantonly appear[s] to undermine his own best interests?" After all, if the only goal is extracting labour from the slave, this is often not the best way of achieving that. However there is another form of extraction occurring—that of status and standing. In the dishonouring of the enslaved person, the enslaver indulges his own sadism and feeds his feelings of superiority and self-esteem.

Honorific parasitism, of which humiliation is one type, is still a structural part of our society. Marxists will be familiar with the continued existence of economic parasitism—it's a metaphor Marx himself used, describing capital as 'vampiric', feeding off 'living labour'. I wouldn't describe all exchanges under capitalism in these terms, but it's certainly appropriate for some. Living off rents, for instance, either literally in the case of being a landlord, or by passively gaining wealth by sitting on an artificially scarce asset (ie a home you bought in the 80's for a fraction of today's price) could reasonably be described as parasitic. Samantha Hancox-Li convincingly argues that such economic parasitism is not only a core part of the American economy, but a key driver of our political dysfunction. Economic rent-seeking combined with social rent-seeking (being granted a certain status simply by being white, or male, and so on) are the foundation of the 'plutocrat-populist axis'.

Humiliation is yet another type of human parasitism, one enabled by the power structures of our society. Sometimes those power structures will be simple and clearly defined. Sometimes a cloud of smaller power imbalances will combine to create an effective relation of domination. Consider:

Fatima is 25 years old and is in her second week working as a barista in a chain coffee store. One lunch rush she's been left understaffed, with a couple of colleagues she doesn't really know trying to clear a persistently building queue. In the rush, she gets a customer's order wrong. He's—let's call him Mark—45, white, causally but nicely dressed, in shorts and slip on shoes with an expensive watch. "What's this?" he asks, pointing at his drink. Fatima repeats the order back. "And is that what this is?" Mark asks, slowly, like he's talking to a child, but without any warmth. Already flustered she apologizes and offers to make another, but he's not done. Of course he would like another. How did she mishear him? He was very clear. He's not raising his voice, but he's locked her with eye contact, unsmiling.

"Fa-ti-ma", he reads her name off her tag, overpronouncing it with a slight mocking inflection. "How long have you been doing this job, Fa-ti-ma?" She answers, truthfully, she's still in training. "Well, I would have thought they'd train you better." He gets the flash in her eyes he was looking for. But she bites her tongue and looks down. She doesn't know the guy who hired her—he seemed fine, but hardly caring. She's no idea if he'll side with her if she's rude to a customer or gets complaints. She's still stabilizing financially after a period between jobs. And this customer is the sort who'll make a well-worded complaint, in professional language, the type management responds to. She looks around vaguely, but she doesn't know the other staff. And they're busy anyway. The other customers seem annoyed with her for the delay. "Well?" Mark wants to know. She mumbles another apology. "What was that? Speak up" He will not let it go. And he'll do it again when she comes back with the correct drink. Making her apologise yet again, telling her she isn't very good at her job. Mark leaves the interaction with a bounce in his step, energy pumping through him. Fatima will allow herself 5 minutes to cry in the employee bathroom. But only after they've got through the lunch rush. She doesn't tell her boss, but if she did, he'd tell her she "did the right thing" by not "rising to it." She leaves her shift still angry.

A collection of power imbalances have come together to create an effective relation of domination. Mark is in the more powerful position, and he's going to impress that fact on her. Why? Part of the power he's leveraging is economic, but that's not the motivation (the sale of the coffee remains the same). Rather, it's an aggressive form of honorific parasitism; he's going to undermine her dignity, her self-respect, to feed his own. Parasites may depend totally on their hosts (actual vampire bats can only drink blood), partially, or not actually need them at all. Mark is the latter—he has many other ways to boost his ego. He in no way needs to do this.

Parasites can also be more or less efficient; from not even being noticed by their hosts, to killing them. Mark's humiliation of Fatima—indeed almost all instances of humiliation—are a very inefficient form of parasitism. He will ruin her entire day, and quite possibly cause her lasting harm, just to feel good about himself for a few moments. This can be done with some sort of instrumental goal (tacitly, subconsciously) in mind. For example, Kate Manne distinguishes between patriarchy (a system of power) and sexism (a theory justifying that system) and misogyny, the "enforcement arm" of that system. Humiliation can have a similar 'enforcement' role—Mark may have felt offended at Fatima (someone of lower status) making him (of higher status) wait, or perhaps even of addressing him without proper deference, and decided to put her 'in her place'. Similarly, humiliation can serve as a warning to others by making an example of those who 'get out of line.'

A lot of the time though it is purely sadistic parasitism. People do it because they enjoy it. Mark—as I imagine him—has a good eye for powerlessness, and will take opportunities to humiliate others when they present themselves. Gratuitously. Without needing an excuse. He is, simply, a parasite—drawing sustenance from the suffering of others.

Isn't this, to a degree, true of all forms of status? After all, to be 'high-status' necessitates others to be low. The prestige of winning a sports competition comes at the expense of those who lost. There is indeed something necessarily zero sum here, but humiliation isn't just zero sum, it's negative sum—Mark's gains are slight compared to Fatima's losses. I'd argue humiliation is wrong in ways other forms of status exchange aren't. There's a difference between being lower status, or losing status, and having no status. Being dominated, being shown to be totally powerless. The losers of a sports tournament may be disappointed, even embarrassed, but in normal circumstances they are not humiliated. They still retain some standing.

Contrast Fatima with a pub landlord—that great stock character of British literature and social life. Let's call him John. He has had the job 15 years, is a well-established part of the community, is white, male, and, crucially, owns the establishment he is performing customer service at. The power relations, the comparative standing, between him and customers is very different. As a result, he conducts himself with a certain amount of dignity, even pomposity. He is not at the top of the hierarchy, but nor is he dominated. If a wealthy landowner stopped by for a pint, he would be John's superior in both wealth and social status. Nonetheless, if he became truly unpleasant John could (and would) kick him out, and the community would tacitly accept he was within his rights to do so.

Two types of 'populism'

Once people get a taste for humiliating, they will fight very hard to be able to keep doing it. Like an addiction, the competitively powerful will often put this urge above all else and behave in profoundly self-destructive ways to chase it. People with others beneath them in a racial caste system almost always prioritize maintaining it over their own economic, social, or cultural interests. As America recovered from COVID, a tight labour market and rising wages for those in service positions partially mitigated some of the power imbalances that allowed Fatima to be humiliated. And the Marks of the world reacted very, very badly to that.

It's often opined that Trump would be more effective if he were capable of some restraint. That a truly dangerous autocrat would mask his designs better. This not only misses a huge part of his appeal, but what one of the central aims of this movement is.

Many millions of Americans love Trump because he routinely humiliates people. It validates their own actions. They live vicariously though him, imagining the humiliation they could inflict if they were given greater power. He also normalizes the behaviour. The symbolic power of having someone of his open sadism in the Oval Office is massive. It is changing our society, making humiliation much more acceptable, and corroding the norms that partially restrain humiliators.

Mark, as I sketched him, is a creature of the pre-Trump world. In our era, particularly after the 2024 election, he would go further. Rather than subtly expressing his racist contempt he would drop a slur. Casually, to show that he can. He might call Fatima a terrorist or tell her how much he enjoys seeing her kind killed in Gaza. It's not that these things were never said before—they were—but our culture has become much more accepting of them.

And this cultural shift is coming from the top down. Again, humiliation is an act that moves down social hierarchies. When we talk about the normalization of racism, I think many liberals still imagine working class white supremacist thugs with shaved heads and tattoos. Those people are real enough, but shouldn't be our mental image of MAGA. This is a movement of businessmen, bankers, landlords, car dealership owners, tech bros, cops, those who live in idleness of an inheritance, doctors, pilots, plastic surgeons, religious leaders, farm owners, tradesmen, and news media personalities. Those who, in their interactions with employees, service workers, and staff, could, and did, humiliate, but wanted to go further. And who self-consciously joined a project to change the norms of the American elite so they could.

And they have been remarkably successful. The torture at Abu Ghraib was, in large part, about humiliation. That coming to light was a leak, and people were shocked. Now similar degradation in 'deportations' is being intentionally broadcast for the entertainment of half the country.

It is also a movement of aspirational humiliators—young men, for instance, who feel (and have been indoctrinated to feel) that being cruel to women, putting them 'in their place' is their birthright. It is not that they have lost anything, rather that women have gained something. Groups 'below' you in the hierarchy having more power makes them less susceptible to humiliation (the forced recognition of dominating power). This, to many, is unacceptable. Women pushing back against harassment or abuse, social norms against open racism, and service workers earning more, all limit the ability to humiliate. MAGA is a movement of parasites seeking hosts.

This non-economic, non-instrumentally-rational side to the Trump movement is often swept awkwardly under the label 'populism.' It is imagined that it comes from similar discontents as left populism. That there is an 'anti-establishment' vibe out there that is channelled in different directions, that Bernie and Trump are drawing water from the same well. Using humiliation as a political concept however, we can see that the emotional base of the movements are not only different, but opposite—directly opposed to each other. Right populism is driven by the desire to humiliate, left populism by not wanting to be humiliated. The anger that fuels protest movements often comes from experiences of humiliation.

I was active during the Black Lives Matter protests following George Floyd's killing. My impression was that, for many people there, this wasn't just about that murder—horrific as it was. They were angry. Angry perhaps at their own unpleasant encounters with law enforcement. Angry at various smaller instances of disrespect in their lives. Moments where they were made to feel powerless. Police killings were the spark that activated that anger. It's worth noting that the most high-profile of such incidents, the ones that generated the most outrage, often involved elements of humiliation. Derek Chauvin, knee in Floyd's back as he begged for his life, was—in addition to murdering him—humiliating him. He was impressing on him, violently, his own powerlessness.

While the socialist left is more economic in focus, I think a lot of the energy it draws on also comes from anger at being humiliated. My friend Matt McMannus, a member of this political group, recounted a formative experience for him the last time he was on my podcast:

I've worked a lot of different jobs . . . one of the most important for me was when I was working at McDonalds . . . I'll never forget when my boss used to tell me to go into the dumpster to cut into all the trash because people had thrown stuff away that they weren't supposed to. And it wasn't just me; all the people there had to do this. And he treated us like shit. He was just like 'go do this, and I don't care that you think that's dirty or disgusting, and that it's 50 degrees out' . . . and it's this lack of respect and feeling like you're under someone's thumb that really grated me in that situation . . . it's exposure to things like this that lead a lot of people to become socialist.

As an aside, I think this explains a lot of left anger at liberals. When they say 'middle-class liberal' they're imagining someone who has not had experiences like this and does not understand—indeed, arrogantly dismisses—the perspective of those who have. It isn't a fair characterization of all, or even most, liberals (loads of us have also had shit jobs), but it is of some affluent libs, and it does make them incredibly frustrating to talk to. While there will always be people who will try and stereotype liberals, we could do a better job at avoiding this image, at not letting people like this be the face of the movement.

Finally, we should note that just because anger at humiliation is a significant driver of left-populism, this does not cleanse individuals within it of the desire to behave badly. Indeed, this noble input can often curdle into the urge to humiliate in turn, just to humiliate a different group—"the enemies of the people" (whoever they turn out to be), or even just other progressive factions. And some join precisely for this reason. There's a certain type of lefty (who will be familiar enough to anyone on politics social media), who has some status markers—college educated, usually white and male — but is downwardly mobile relative to their parents, yet still utterly convinced of their own importance and intelligence. To them, the cause is a chance to cosplay as the high-school bully they wish they could've been. They are truly pathetic. Again, this isn't all, or even most, left-populists, but they can often be the loudest ones. The left could do a better job not allowing itself to be defined by them.

This is nothing new

The desire to humiliate and the desire not to be humiliated are huge drivers of our politics, but then, they always have been. So much of our world would be unintelligible to the Roman authors, but the core emotional instinct behind MAGA would have been clear enough to them on its own terms. Sallust wrote of the wealthy:

. . . what hope have you of mutual confidence or harmony? They wish to be lords and masters, you to be free; they desire to inflict injury, you to prevent it; finally, they treat our allies as enemies and our enemies as allies. Are peace and friendship compatible with sentiments so unlike?

Machiavelli—a thinker who drew heavily on Sallust—continually uses the concepts of 'the few' and 'the many' to explain why political events happened. They are presented as in perpetual conflict that, even in a well-ordered Republic, can never be fully resolved. At its root, is the competition of different desires; Machiavelli's "discussion of class-behaviour often appears more psychological than economic". The rich elites, whether the Roman senate or the Florentine Ottimati, were motivated not just by the desire to defend their power and property, but by a contempt for the lower orders and a desire to degrade them.

Destabilization of a state was hence more likely to come from above—"disturbances are more often caused by the 'haves'". Elites would both make incredibly foolish decisions, and provoke occasional explosions of popular anger with their arrogance. History for Machiavelli was an endless cycle of these forces that repeated, but never fully resolved.

Our world today is more democratic, giving 'the many' more opportunity to check elites. But it is also much more affluent—there are many, many people who can afford to have coffee made for them every day. This affluence can allow the middle-class opportunities to humiliate others, and we have often structured our economy to provide them. As wealth has concentrated at the top in recent decades, the oligarchs have (in a way that would have been obviously predictable to Machiavelli) become all the more parasitic in their honorific demands. It's never enough for them to live in unimaginable luxury. We must all always be praising them, never contradicting them. They have now found common cause with a much larger assortment of parasites and aspirational parasites and are in the process of making our world a much crueller and more unstable place.

Domination and freedom

If humiliation is a big factor (not the only factor, but a big one) in explaining why political events happen, does that mean it also impacts how we should think morally? That it should influence what type of world and politics we should aim for?

I think so. To put it in wonky terms, humiliation is both an important descriptive concept and an important normative one.

To start with, the converse of domination is often taken to be freedom. There is a long tradition in political philosophy of defining freedom as not being dominated. That to be free, it is not enough to not have anyone actively interfering with you, there shouldn't even be anyone in a position to use power over you in an arbitrary and unaccountable way. The story I've told buttresses that: If domination is persistently used to humiliate, and humiliation is harmful, then that's yet another reason to avoid domination.

I think it also tells us something about the nature of domination. It's not just that it has bad effects, or that it can be abused, there's something intrinsically inhuman about it. We all have a deep need to make certain core status claims for ourselves. That we deserve a certain minimum of dignity, that we are an agent whose desires matter, that we are not simply a tool of others. Humiliation is wrong because it destroys those status claims, but it also shows how incompatible domination is to those core human needs. So much so that being forced to look directly at domination is a grave form of psychological harm to people. It is fundamentally destructive of our ability to stand in community with others, and hence our humanity.

Humiliation allows us to ethically distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable forms of status exchange. People, after all, will always compete for praise, recognition and standing. And to some extent, this is always at another's expense—you need to exceed other people to win the tournament. And you can do so, you just can't dominate them—that's the ethical line. That violates their fundamental dignity as a person in a way that simply gaining more recognition does not. It is also far more destructive of the bonds between us. A losing sports team might (assuming good norms of sportsmanship) be happy to join the winners for a drink after the match. Fatima would never (willingly) go for a drink with Mark. It is not possible—as philosophers have long recognised—to have a society, particularly a complex society like ours, with no distinctions of status. It may be possible to ensure everyone has a certain minimum. And humiliation shows why 'not-dominated' is the minimum we should aim for.

What does this mean for freedom? First—and most obviously—it means that freedom is about having power, not just being protected from it. It's not only a matter of constraints on the powerful, but of actively empowering all of us. Yes, freedom is not being dominated, but we might go further: Freedom is having the power to not be made powerless.

A free society is one of confident pub landlords, not isolated and insecure baristas. I do not think this means we need to do away with all market exchanges, but those with the potential for humiliation (which is to say those with domination) must be restructured. More empowered workers, the end of Employment at Will, democracy in the workplace, bottom-up wage growth, and so on are all obvious places to start. Hierarchies based in race and gender are also enemies of freedom in this conception, as are extreme concentrations of wealth (and hence power).

This provides a freedom-based argument for workers cooperatives, public institutions, and a strong public sector. That these institutions create barriers to humiliation is one reason why the right opposes them. For instance, I've often suspected the real bone-deep hatred many American conservatives have for the DMV is because their staff have greater job security and are hence harder to humiliate. Their stereotype of a DMV worker is of a middle-aged-to-older Black woman who will not tolerate being disrespected. The mere thought of this is enraging to them.

Freedom, seen from the view of humiliation, is not just about formal rules and economic structures. Being free is also about the type of society you live in; the kind of norms people abide by. These matter. People, I find, can all too easily jump from recognising that people desire to dominate to assuming it's an intrinsic and unchangeable part of human nature. Hence, that there's nothing really to be done about it. We shouldn't allow ourselves to fall into this fatalism. The parasites have effected a great change in norms to make it easier for them to feed on us. These things are not fixed in stone. We should be equally ambitious in forcing not just a change back, but moving towards a truly decent society.

Part of the reason Fatima was able to be humiliated is she did not have strong relationships with her coworkers. Also, none of the other customers saw it as their role to challenge Mark, and her boss would have praised her for not challenging him herself. All this at least tacitly endorses the view that Mark's actions were acceptable. In a truly free society, people of different jobs and backgrounds would share a resolve to not allow one another to be treated this way. At the level of belief, a critical mass would be united in the conviction that everyone should be able to walk with their heads held high. Weirdly perhaps, this is not a million miles from how Machiavelli thinks of freedom. For him, to be in a state of non-domination 'the many' must perpetually reassert themselves against the desire of 'the few' to dominate them. What emerges is a conception of liberty as an active holistic property of 'the people' as a whole, a set of traditions, customs, mores, and attitudes. Constitutional design and laws are ways of maintaining this liberty, but do not in themselves constitute it.

I would add to this that the project of liberty is also one of rebuilding and reconstruction, not just of our society, but of ourselves. Being humiliated strips away our bedrock of our sense of self, it leaves us alone and angry. Liberating a society will require mutual reaffirmation of our dignity and worth. To be free—in the term's oldest roots in the Indo-European language—is to be "among the beloved." Taking the time to listen to a person, meeting their eye, gently correcting them if they put themselves down too much, remembering names, or, in the digital post-COVID age, commenting on people's pet, food, and nature photos—telling them how good their home baking project looks and so on—these are not just nice things to do, they are liberatory practices.

Those subject to humiliation have always found ways to rebuild their ties with others, their dignity and self-worth. Consider for instance fictive kinship—referring to members of a group as 'brother' or 'sister'. This is common to religious communities that are (or started life as) a despised minority, historically oppressed racial groups such as Black Americans, and workers groups such as unions. It bonds the group, but also affirms that the person is valued, that they are, in a sense, among the beloved.

There is much more to say on all of this (how, for instance, does this vision of freedom reconcile with a liberal one?) For now, I just want to make a comparatively simple point: humiliation is not just an unpleasant or unethical act, it is politically important. Politics is—and always has been—significantly impacted by it. Moreover, when we try and think clearly about what humiliation is, we see that it has significant implications for our ideal of freedom, and our vision of politics more generally.

Political philosophy often starts by imagining people at their very best—at their most rational, most cooperative, most long-sighted—and works backwards from there. I want to ask what emerges when we start with people at our very worst.

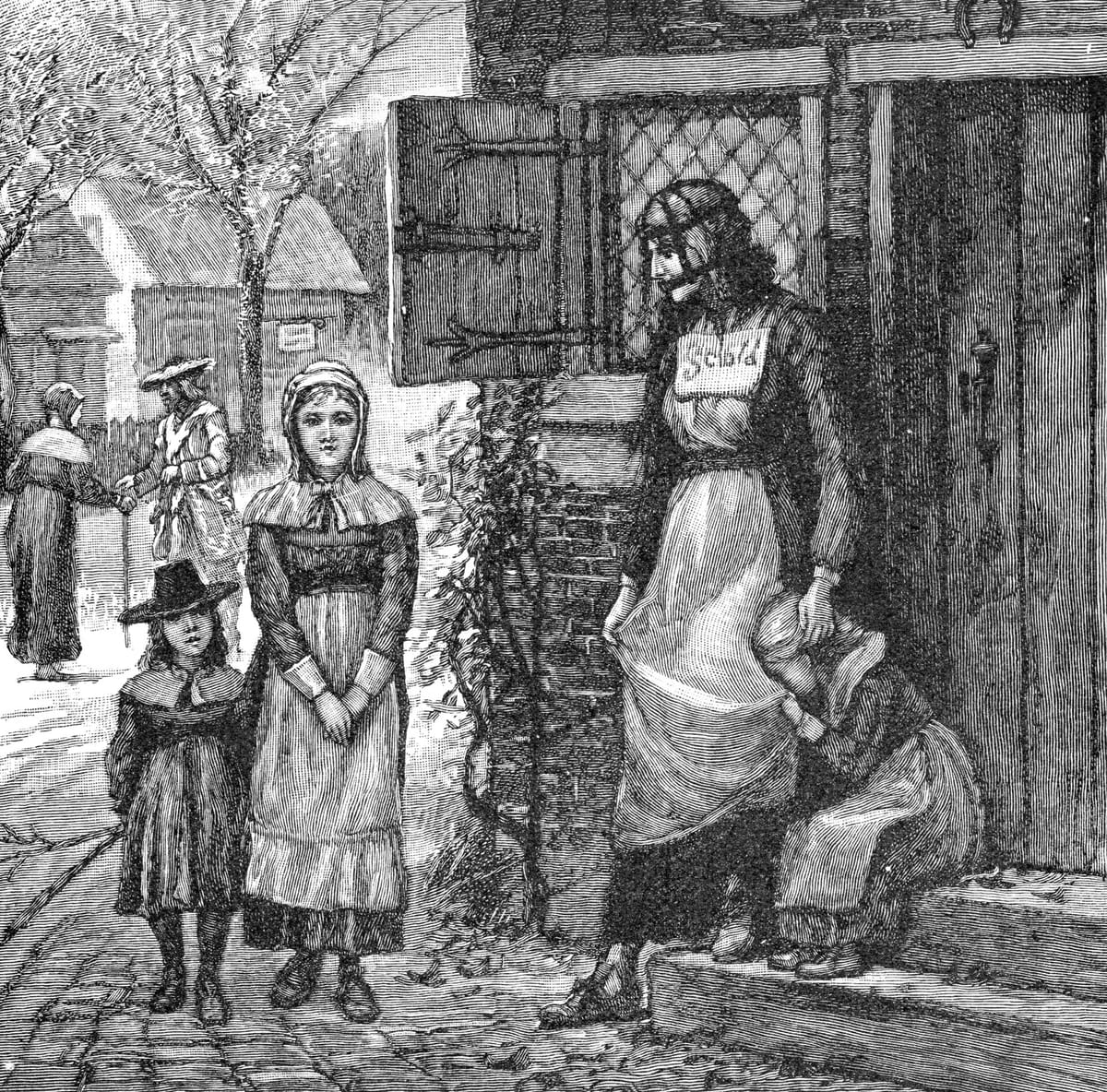

Featured image is "Engraving of a scold's bridle and New England street scene," Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele 1885