The Politics of Fear in American History

The precedents for the violence and overt use of state power we are now experiencing can be found in the 1910s and 1920s rather than the 1930s and 1940s.

At its best, liberalism works to appease the fears of humanity. At the forefront of people’s minds most of the time is the fear of cruelty and violent death. Being well-acquainted with this feeling, the liberal men and women of early modern Europe endeavored to put the problem of cruelty at the top of their political agenda.[1] Benjamin Constant, a Swiss philosopher who made it through the French Revolution in one piece, saw it as the duty of liberals to arrange government in such a way as to mitigate the risk of civilian victimization. "From the fact that it is easy to commit errors in legislation," Constant argued, "and that errors of this kind are a thousand times more harmful than all other calamities, it seems to me that one should decrease the chance of these errors as much as possible."[2]

The failure of liberal-minded politicians to keep government officials accountable is a cause for great fear, especially when those state actors are perceived to be actively and intentionally undermining the public’s sense of security. As the American philosopher Judith Shklar explains, what she calls the "liberalism of fear" regards "abuses of public powers in all regimes with equal trepidation." Knowing that "every page of political history" teaches that "some agents of government will behave lawlessly and brutally in small or big ways most of the time unless they are prevented from doing so," a liberalism that considers the propagation of fear in society an evil will worry "about the excesses of official agents at every level of government."[3]

The politics of the second Trump administration is a politics of fear. A case in point is the campaign of censorship, firing, and social ostracization of those who express critical views of the late Charlie Kirk and the MAGA movement he supported. Vice President J.D. Vance urged his political supporters to report anyone who dared to exult in the death of the conservative commentator: "When you see someone celebrating Charlie’s murder, call them out. And hell, call their employer." Elon Musk, the owner of the social platform X, also joined the chorus of influential voices calling for the termination of outspoken employees, but went further than most in recommending the deplatforming and imprisonment of dissenters.

Weighing in on all of this, Attorney General Pam Bondi, added that making fun of Kirk’s violent death was hate speech. "We will absolutely target you, go after you, if you are targeting anyone" with that kind of ‘hate speech’. When asked by ABC’s Jonathan Karl to clarify what the Attorney General meant by that threat, Trump replied that Bondi would "probably go after people like you," (journalist, that is) "because you have a lot of hate in your heart."

After the FCC Chair successfully, if temporarily, pressured ABC to take Jimmy Kimmel off the air, President Trump suggested that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC for short) should investigate other shows for criticizing him: "They’re giving me all this bad press…I would think maybe their license should be taken away." Broadening the scope of investigation, Vice President J.D. Vance promised to prosecute political organizations that not only fund hit pieces against the President and his allies, but also support the activities of political groups that oppose the current regime. At the top of his list of targets were any left-wing NGOs that "foments, facilitates and engages in violence."

Stephen Miller, the White House Deputy of Staff, offered the following solemn pledge, "With God as my witness, we are going to use every resource we have at the Department of Justice, Homeland Security, and throughout this government to identify, disrupt, dismantle, and destroy these networks and make America safe again." He added on a later occasion, "the power of law enforcement…will be used to take away your money, take away your power, and, if you’ve broken any law, to take away your freedom."Laura Loomer, Trump’s close aide and closed-door whisperer posted on X that "I want the right to be as devoted to locking up and silencing our violent political enemies as they pretend we are." Since then, President Trump has announced his intention to designate the leftwing group antifa as a "major terrorist organization."

Democrats and liberals seeking to understand the terror of this moment have looked to the darkest periods of American history to help them make sense of what is going on in their country.[4] "We are in the biggest free speech crisis this country has faced since the McCarthy era," said Texas representative Greg Casar. Zack Beauchamp, a senior correspondent for Vox Media and the author of The Reactionary Spirit: How America’s Most Insidious Political Tradition Swept the World, announced that the government’s response to the assasination of Charlie Kirk marks the beginning of a third Red Scare.

There is no disputing that the government’s fierce avowals are reminiscent of the days when the C.I.A and the Justice Department were out to catch socialists and other leftist groups. Ridding the body politic of radical elements has been a dream goal of the American right for more than two decades, but with the arrival of Donald Trump these dreams seem much more vivid. During a 2023 campaign stop in Durham, New Hampshire, Trump pledged to "root out communists, Marxists, and fascists, and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country." That same fall, Trump also declared that something had to be done to stop "illegal immigrants" from "poisoning the blood of our country." Some historians pointed to similarities between the president’s comments and Adolf Hitler’s assertion in Mein Kampf that the great civilisations of the past "died out from blood poisoning."

But we need not look abroad to find parallels to what Trump is saying and doing. After all, it was President Woodrow Wilson, not Adolf Hitler, who first condemned foreign-born residents for pouring "the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries" of American life. There are good reasons to think that the 1910s and 20s offer the best historical timeframe to understand what the right is up to, rather than the 1930s and 40s.[5]

As the New York Times columnist and former First Amendment lawyer David French noted, it wasn’t until 1925 that the Supreme Court enforced the First Amendment's free speech protections at the state level. Looking at the present strife in America, French posed the following question: "Is America a more or less just nation than it was in 1925? Is it more or less hospitable to historically marginalized groups?" The answer to these questions will invariably depend on people’s knowledge of the period. This article is an attempt to help people answer these questions for themselves.

The firm hand of stern repression

The period between 1914 and 1930 was one of the most politically repressive eras in American history. The title of Adam Hochschild's latest book, American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, suggests as much. America’s entry into the First World War ushered in one of the darkest phases in the nation’s history. The civil liberties of millions of Americans were extinguished by the stroke of a pen. Government spies and vigilantes roamed the streets in search of ‘enemy aliens,’ the offices of labor unions and radical left magazines were raided by government agents, political dissidents and workers on strike were kidnapped in the dead of night and either thrown in jail or murdered, isolated camps with barbed wire fences and armed guards were created to house protesters, and an entire government bureaucracy was erected to keep everyone in line.

This American midnight began with a set of decisions at the top. On May 18, 1917 President Wilson introduced the Selective Service Act, requiring all physically eligible men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty to register for the draft. Then on June 15, 1917 (barely two months after the United States had declared war against Germany), President Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act into law. The law prohibited the sharing of any information that might hinder war efforts or dissuade citizens from enlisting in the military or obeying army commands.

The law also empowered Albert S. Burleson, the Postmaster General, to monitor the correspondence of citizens, and where necessary, to revoke mailing privileges. Those found in violation of the terms of the new law against enemy espionage could face a fine of up to $10,000 and/or a prison sentence of up to 20 years in a federal prison. Under the Sedition Act, passed a year later, it became a crime to criticize or work to undermine the American political system, its constitution, military, and symbols, including the flag of the United States and the uniform of the United States Navy and Army.[6]

George Ingram, a black chauffeur living in Memphis, Tennessee, would become one of the first Americans to experience the reach of the government’s power. On May 22, 1917 a black man named Ell Persons was lynched in Memphis, Tennessee, before a crowd of at least five-thousand people. The Persons case was one of a number of so-called ‘spectacle lynchings’ that took place in the south during the war years. Spectacle lynchings were public executions of the kind ‘decent folk’ would travel long distances to witness with their small children, picnic basket in hand, and dressed in their Sunday best. Persons was accused of raping and killing a white girl, and was set to face trial for this alleged crime.[7]

Before the criminal proceedings could begin, Persons was abducted and brought near the site of the original crime to face the wrath of the public. The time and date of the execution was posted in the local newspapers as an invitation for the public to attend: ‘Ell Persons to be lynched near scene of murder, may resort to burning," said the Commercial Appeal. People came from all over the city to watch Persons die. Mobile businesses drove to the execution ground to sell drinks and sandwhiches to spectators, and automobiles lined up the road leading up to the epicenter of the lynching. African-American cab drivers abandoned their cars on the road for fear of being attacked. Persons was chained to a large log waiting to meet his fate. When satisfied with the turnout, the master of ceremonies gave the order for Persons to be lit up.[8]

Eager executionists hurriedly poured gallons of gasoline on the victim and had to be told to slow down to allow Persons to die a slow death. After a change in tempo, Persons was set on fire. His charred body was then dismembered and either sold on the market or kept as a souvenir. One man cut the heart, two others the ears, and one man simply cut the head off completely. As the rest of the body naturally fell to the ground, women with babies in their hands stampeded past each other to grab whatever bodily parts they could get their hands on. Despite the torrential rain that set in deep into the night, crowds stayed late at night socializing around the smoked remains, while others took an early break from the festivities, and went back home to get some well-deserved shut-eye. A few spectators returned the next day to catch a glimpse of the body, and perhaps go home with their very own token of remembrance.[9]

Intending this to be a warning to black folks in Memphis, a ten-year old black boy was carried by the crowd to see the burned body up close. "Take a good look boy…This is what happens to n—— who molest white girls", the crowd threatened. Another band of white men threw Persons’s decapitated head and foot in front of a group of African-Americans standing near Beale Street and Rayburn Boulevard. Driving off in a car, they yelled "take this with our compliments." As for the other pieces of Persons’ body that were enthusiastically sliced off like a hock at a barbecue roast, some of them showed up in market places or shops. One barber was arrested by the Memphis police for displaying part of Persons’s ears on the window shop.[10]

Overwhelmed by the events of that day, George Ingram told his co-workers, "Well, we’re through boys. Take your flags off," and ripped the American flag off his car. Always on the lookout for ‘thought crimes’, the Department of Justice arrested Ingram under the Sedition Act for degrading the American flag.[11]

The same flag, mind you, which many men within the Wilson administration thought blacks unfit to wear on their military uniform, never mind die for.

It was not uncommon in those days to hear politicians like Mississippi senator and white supremacist James K. Vardaman complaining, "impress the Negro with the fact that he is defending the flag [and] inflate his untutored soul with military airs," and next thing you know, he will be demanding that "his political rights be respected." In the mind of some southern racists, respect for a banner that did not include them, and did not protect them, even from a painful death, was one way in which blacks could show subservience to whites.[12]

As such, no arrests were issued for obstruction of justice, and no serious attempt was made to save the life of Mr. Persons. Despite the fact that the Memphis police department had 277 active police officers on duty that day, they were no match for a determined mob of at least five thousand. On the day the lynching occurred, the government of the United States intervened to punish Ingram for his ‘anti-American’ speech. The nation that billed itself during the war as the world’s ‘last hope for freedom’ did not even bother to save or even avenge a man who was robbed of his life in the most barbaric manner possible.[13]

With these legal weapons in hand, the Wilson administration was now in a position to impose its military agenda on the public; a task which fell on the shoulders of the Department of Justice, first headed by Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory, and later by the notorious A. Mitchell Palmer. To meet the alleged threat of foreign-born betrayal on American soil, President Wilson called on Congress to prepare such laws as would enable the government to deal with those who "preach and practice disloyalty." Such creatures of "passion, disloyalty, and anarchy", he warned, "must be crushed out"of existence. Should there be any disloyalty, the president threatened, the government would not hesitate to impose its "firm hand of stern repression."[14]

A reign of terror

The first group of people to feel the state’s ‘stern repression’ were German residents. The Wilson administration required all German-born, non-citizen men over the age of fourteen to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’. Once on the federal registry, one could be apprehended, interrogated, and held by authorities at any given moment. Enemy aliens were also forbidden from entering Washington, D.C., making the capital a German-free zone. German non-citizens who failed to satisfy the government's criteria of innocence were placed under permanent detention at one of three German internment camps in the state of Georgia and Utah.[15]

By executive order, close to 11,000 German residents of the United States were detained in barbed wire camps, and forced by armed guards to wake up every day at 5:45 am to perform a full-day of labor for the state. The internment of an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War Two is rightly remembered today as a shameful episode in American history. Regrettably, the plight of German residents during the previous global conflict has received much less attention from the mainstream media. By the end of the war, a full eight percent of the 2.5 million Germans living in the United States had been interned under the Wilson-approved sedition act.[16]

The furor against all things German did not stop with the government’s alien registration and internment program. The government led the way in shaping the American public’s view of German people and culture by pumping out anti-German war propaganda through its Committee on Public Information (or CPI). Under the directorship of the newspaperman George Creel, the CPI churned out newspaper articles and movie reels demonizing German people. American audiences were presented with government-approved movies such as The Claws of the Hun, The Hun Within, and The Beast of Berlin. To get a sense of the flavor of these movies consider The Prussian Cur. In this silent film, the Klu Klux Klan—of all groups—show up in a midwestern town that has been overrun by German spies. Thankfully, this loyal band of mounted heroes arrive just in the nick of time to rough up the town’s enemies. In a final act of subjugation, the defeated conspirators kiss the American flag.[17]

During the scheduled intermission period, it was not uncommon for Four Minute Men to appear before theater audiences to deliver a short, poignant message concerning the war effort. While the projectionist worked backstage to replace the film reels, the four-minute men used the few minutes at their disposal to remind audiences that—among other things—this war was being fought against a barbaric enemy. Once the projectionist was done, the speakers would thank their audience and exit the front stage, at which point the program would resume.[18]

As Hochschild explains, the success of these films, as well as the reach of other forms of government propaganda, helped turn Americans against their German neighbors. Respected public officials and mainstream newspapers repeatedly warned the public that German spies were everywhere. Americans were encouraged to remain vigilant and to report any suspicious activity or person. Answering the call of duty, the Justice Department received up to 1,5000 letters a day from concerned citizens. As is often the case with these snitch lines, innocent people were caught up in the wave of hysteria.[19]

Hochschild mentions the case of the young Eugene O’Neil who was arrested at gunpoint for using his typewriter on a sunny beach day (someone mistook the gleaming reflections bouncing off the metal typewriter for coded signals). Mr. O’Neil’s encounter with the war authorities was thankfully brief and bloodless. Other suspects, on the other hand, were not so lucky. On a number of occasions, German speakers were battered, tarred and feathered, and in a reenactment of the humiliation ritual found in movies such as The Prussian Cur, forced to kiss the American flag. In the District of Columbia, a man who refused to rise in homage of the ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ was shot to death by an audience member. According to the Washington Post, when the man fell to the ground, "the crowd burst into cheers and hand clapping."[20]

In midwestern states such as Minnesota and Illinois, public officials eagerly embraced a no-tolerance approach to disloyalty, creating what some scholars have called a veritable "reign of terror in the middle west." More often than not, this stringent policy took the form of outright xenophobia, and on some disturbing occasions, even led to flagrant murder. A Minnesota area judge was not alone in expressing the popular view that, "the disloyal element in Minnesota" was "largely among German-Swedish people." Clearly animated by a desire to stump out this disloyal foreign presence, he also expressed regret at the government’s failure to eradicate European spies when it had a chance back in 1914: "the nation blundered at the start of the war in not dealing severely with these vipers."[21]

To make up for this federal oversight, William Harding, the governor of Iowa, famously banned the public use of any foreign language, effectively forcing all German-speaking Iowans to resort to English when attempting to make telephone calls to family relatives and friends. Such inflammatory remarks and discriminatory state laws reflected the popular mood in some midwestern towns, where even ordained ministers suffered mob attacks. In Minnesota, a German-speaking pastor was tarred and feathered for offering to pray for a dying woman in the language she found most comfortable. In McLean County, Illinois, the ministry team at a Lutheran Evangelical Church suspended their German language service for fear of being attacked by a three-hundred-strong civilian mob. Ministers in other parts of the country were not safe from public fury either: in Berkeley, California, a pacifist preacher was tossed into a church baptismal pool for his anti-war sermons.[22]

The most shocking attack on a German-born resident of the United States during the war period was the lynching of Robert Prager in Collinsville, Illinois. Accused of being a socialist troublemaker and company spy, Prager was seized by a group of local miners, stripped of his clothes, wrapped in an American flag, and forced to walk barefoot down the street. He was rescued by a policeman and put in jail before the mob could carry out their plan. Alas, a crowd of at least 200 people returned after midnight to collect the thirty-year old union member. They proceeded to hang him on a hackberry tree outside the city limits.

The eleven men who were tried for participating in this lynching were acquitted after merely twenty-five minutes of deliberation. The trial itself was a celebration of American patriotism: the accused adorned themselves in red, white, and blue ribbons, posed proudly in front of the court before adoring crowds, and were serenaded by a band that played the national anthem during court recess. The defense lawyer in the case praised his clients for this "patriotic murder", and the Washington Post looked on the whole affair as a "healthful and wholesome awakening in the interior parts of the country."[23]

When not instigated by popular mobs, punishment for disloyalty was meted out by members of the American Protection League. An official arm of the Department of Justice, the APL counted as members a number of hardened veterans from the previous wars in the Pacific. This included Thomas Crockrett, a relative of the legendary frontiersman, who could now ply his skills as administrator of the ‘water cure’ (a crude form of waterboarding) to resisting enemy aliens at home. For a small fee, members of this vigilante group received a token badge, allowing them to cosplay as town sheriffs.

The group also used secret codes. They relished the anonymity and viewed themselves as "soldiers of darkness" undertaking covert missions in the urban jungles of America. This kind of ‘secret service’ work was attractive to men who were itching for action on the battlefield, but due to age or health were not able to partake in the hostilities in Europe. As Hochschild notes, "by joining the APL you could battle the enemy right here—and still go home for dinner every night."[24]

While clearly imprudent, the severely understaffed Department of Justice had no choice but to hand over surveillance duties to passionate outsiders. At 250,000 strong, the APL formed what historian David Kennedy called a "posse comitatus on an unprecedented national scale." Nicknamed the "Ku Klux Klan of the Prairies" by a South Dakota official, the APL often acted as a lynch mob, whipping state enemies across the country, and forcing at least a hundred people in Staunton, Illinois to kiss the American flag in public. The APL helped keep citizens on their toes, ensuring that millions of American residents, citizens and non-citizens alike, remained anxious about the possibility of being molested or prosecuted by authorities for committing vague acts of disloyalty.[25]

Under threat of verbal intimidation and violence from official state agents and sanctioned vigilantes alike, cowed citizens willingly did away with all things German. Seemingly overnight, the word ‘German’ became anathema in polite society. Berlin, Iowa became Lincoln, Iowa, sauerkraut was rebranded as the ‘liberty cabbage’, and the frankfurter was renamed the ‘hot-dog’. The attempt to rename the hamburger the ‘liberty sandwich’ clearly did not stick, but it was not for lack of trying. The arts also suffered: Mendelssohn’s ‘Wedding March’ was dropped from wedding ceremonies, and other giants of the German classical tradition were temporarily discarded by musical societies. German-speaking conductors were disinvited, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra hired two detectives to keep tabs on musicians who were suspected of being enemy aliens.[26]

Karl Muck, a Swiss musician who was considered at the time to be one of the world’s foremost conductors, was arrested by the Boston police in the middle of a rehearsal of Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion. Hochschild reports that the police officers actually looked through his annotations, suspecting that his scribblings might stand for secret codes. While nothing came of it, the suspicions harbored against him were sufficient to send him to the internment camp at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia. While under detention, along with 4,000 Germans, he conducted a moving prison-rendition of Beethoven’s Eroica before an audience of more than 3,000 detainees.

Richard Goldschmidt, an esteemed geneticist who played the violin on that occasion, said of the performance: "I do not think that a symphony ever created a more profound impression than this upon thousands who had probably never before heard classical music.” The United States government had in effect created a political climate so thoroughly and pedantically opposed to German culture that the best place in 1918 America to hear Beethoven’s music without fear of interruption and reprisal was probably within the confines of a German internment camp.[27]

An avenging government

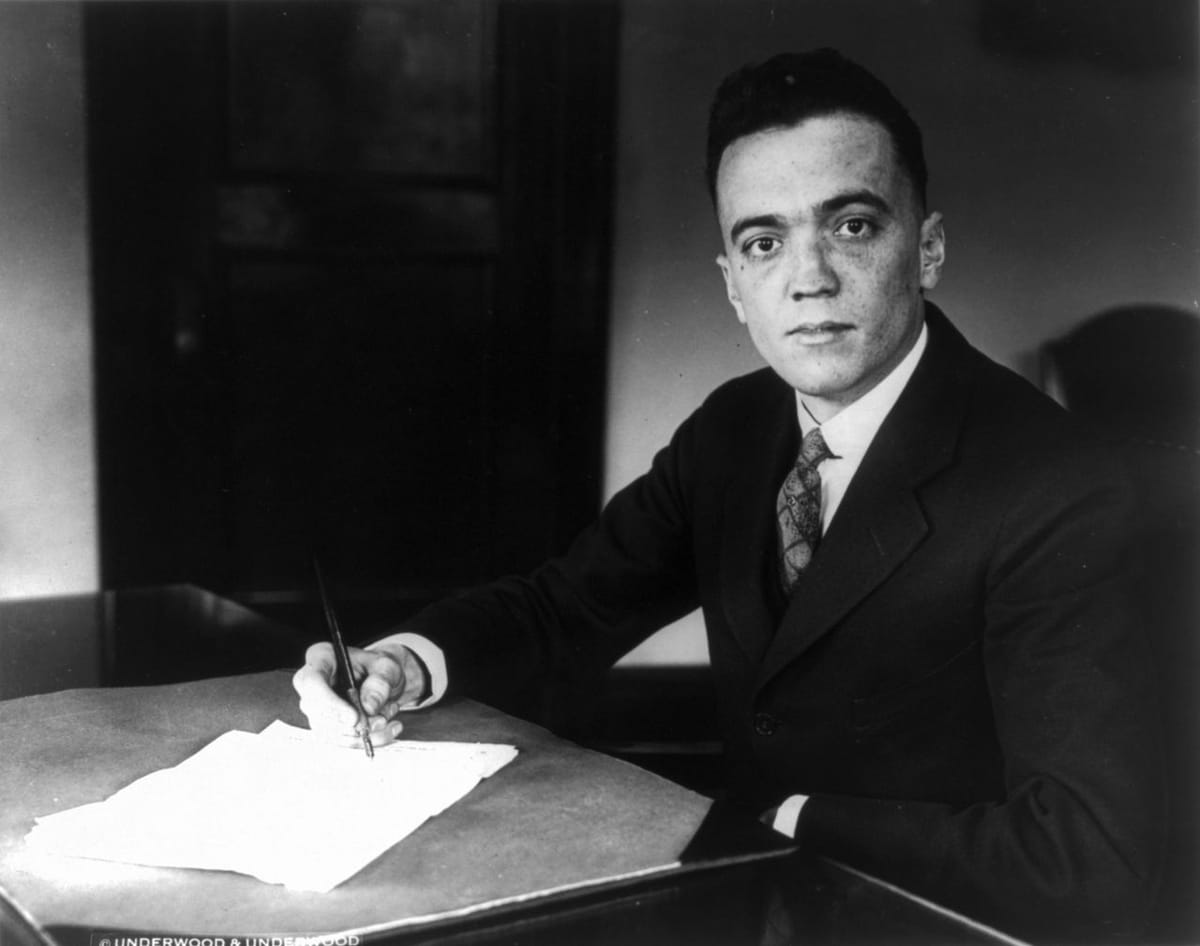

At the center of this repressive bureaucracy was the obsessive FBI official J. Edgar Hoover. As Beverly Gage reveals in G-Man: J.Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, the young Hoover was the administrative genius behind the large-scale arrests and deportations of left-wing dissidents during the last term of the Wilson presidency. Hoover entered the Justice Department in the summer of 1917, just as the government was putting together its internment program. After reviewing the facts of a case, Hoover would offer his judgment on whether a particular individual should be put away in an internment camp. In the absence of a formal hearing or trial, or any adherence to due process law, the decision to send someone to a labor camp was ultimately left to the unique sensibilities of the person processing the dossier.[28]

Gage reports, for example, that Hoover sent a man to camp detention for calling the president "a c—k-sucker and a thief". At other times, Hoover seemed much more lenient: he chose not to intern a German man who said, "F— this god— country." Hoover’s bosses chose to make up for this moment of weakness by overruling his decision, and send the man to labor camp anyway. Setting the tone for the entire Justice Department, Attorney General Thomas W. Gregory promised the American public that his organization would show no mercy to disloyal elements: "May God have mercy on them" he warned, “for they need expect none from an outraged people and an avenging government."[29]

With the blessing of the attorney general, Hoover now turned his attention to socialist rabble-rousers and their associates in the labor movement. Over the course of several months, starting in November 1919 and ending in May 1920, the F.B.I. raided the offices, printing houses, and meeting places of socialists, communists, and labor organizations. The bureau arrested thousands of people every month, beating some, jailing others, interrogating many, and in the end, releasing most of them without ever having to produce a warrant or inform the targets of their right to consult a lawyer. Attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer is often credited for overseeing this government crackdown on socialist thought, but as Hochschild and Gage point out, the "Palmer Raids" were a misnomer. The real brain of the operation was undoubtedly J. Edgar Hoover.[30]

Over the course of five months, thousands of foreign-born residents would receive a visit from government officials, either at social events or at their place of residence. Some arrestees were taken to jail without ever being told what crime they committed. It was also quite common for victims to speak to authorities without first being told that their words could be used against them. Once in jail, the arrestees faced the prospect of a long, indeterminate period under confinement unless they were able to raise the cash needed to post bail. Thomas Truss, a Polish immigrant with three American-born children, was arrested without a warrant, interrogated without a lawyer, and held in jail for a week until he was able to come up with a $1,000 bail. Truss never attended any communist meetings. What got him in trouble with the law was the delivery a communist party membership card to his home address.[31]

Unlike Mr. Truss, Sonia Kaross’s connection to socialism went beyond a mail order. Kaross was a bookkeeper for a small socialist newspaper and a card-carrying member of the communist party. As a Lithuanian-born socialist sympathizer, Kaross knew that her activities might get her in trouble with the government. In It Did Happen Here: Recollections of Political Repression in America, she recalls the intense feelings of fear which gripped immigrant communities following the Goldman deportation: "At the time, there was a rumor that all the foreigners were going to be deported…we were Socialists. Naturally, we had an intuition that something like that might happen to us. The way the newspapers carried on, there was a scare among the people. And everybody was told to be cautious: don’t have papers, don’t have stuff in the house, because it might happen. Then it did happen." When authorities finally knocked on her door on a Sunday afternoon, they ransacked her small apartment, confiscated all of her books and papers, and took both her and her husband to jail.[32]

Despite being visibly seven months pregnant, Kaross was treated like a common criminal: she was thrown in a van and driven to a prison cell where she was placed in the company of five sex workers. When the stress of incarceration got to her, and her cell mates realized that she might lose the baby, “they raised an awful rumpus. They were screaming and hollering, knocking on the door…yelling, "This woman is dying! Get her an ambulance!" But nobody responded." In the end it was too late for the baby. By the time the ambulance arrived in the morning, the baby was dead. Kaross spent a couple of days in hospital, and went right back to jail.[33]

Kaross was only released from jail when someone brought bail money. Her husband on the other hand stayed in jail for two more weeks until someone finally raised enough money to bail him out. These personal testimonies reveal the painful human toll of the government’s repressive frenzy. Not only did these raids produce needless suffering (from the get-go there was never enough evidence to convict Kaross and her husband of any serious crime), they also failed to achieve their short-term goal. According to Kenyon Zimmer, one of the leading historians of the period, of "the 1,182 suspects seized nationwide on November 7, only 439 were held for a deportation hearing, and less than half of those resulted in removal."

In addition to being tremendously wasteful, the raids were highly unconstitutional. When Secretary of Labor Louis F. Post discovered in March 1920 that thousands of foreign-born residents had been arrested without proper warrants, he invalidated nearly 3,000 arrests and blocked the scheduled deportations of thousands more. So began the ‘liberal blockade’ against the government’s overreach. In the grand scheme of twentieth century politics, the liberal blockade of the 1920s—particularly the decision to put an end to the unconstitutional Hoover raids—was but a minor setback for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Hoover’s impressive organizational skills would enable him to put together the manpower and resources needed to hunt down socialists and other political minorities for the next half a century.[34]

The first Red Scare holds lessons for liberals and their enemies alike. To members of the post-liberal right, J. Edgar Hoover is not an ominous figure, but a pillar of security whose cunning and craft helped save the country from radical subversion. He offers in many ways a model for conservatives who wish to break the power of ‘left-wing radicals’ on campus and elsewhere. As Christopher F. Rufo posted soon after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, "the last time the radical Left orchestrated a wave of violence and terror, J. Edgar Hoover shut it all down within a few years. It is time, within the confines of the law, to infiltrate, disrupt, arrest, and incarcerate all of those who are responsible for this chaos."

While not historically correct (the last wave of repression happened well after Hoover was dead), Rufo’s remarks offers an insight into the mindset behind the Trump administration’s trampling of civil rights in its pursuit of ideological enemies. The current ICE raids against undocumented immigrants, as well as the build-up to an assault on radical elements, are a warning to modern liberals to prepare their own constitutional blockade.

Noting that these moves appeared at first to be an overreach, David French recently wondered:

Can you overreach so much that when you push so far into actual authoritarianism, it has a more intimidating effect than a rallying effect? It’s obvious to me that that’s what they’re heading toward. They’re trying to push all the way through normal American politics and get to a point where they feel like they can dictate the terms of the debate through sheer retribution and intimidation, and cow opponents into silence.

Whether they will succeed, only time will tell.

[1] Judith Shklar, Ordinary Vices (Cambridge, M.A: Harvard University Press, 1984), 7-44.

[2] Benjamin Constant, Commentary on Filangieri’s Work. Translated, Edited, by Alan S. Kahan (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2015), 34.

[3] ‘Judith Shklar, The Liberalism of Fear,’ in Nancy Rosenblum (ed.). Liberalism and the Moral Life (Cambridge, M.A: Harvard University Press), 29.

[4] Clay Risen, Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America (New York, N.Y: Scribner, 2025).

[5] Christopher Cox, Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn (New York, N.Y: Simon & Schuster, 2024), 269.

[6] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (New York, N.Y: Mariner Books, 2022), p.61-63.

[7] Margaret Vandimer, Lethal Punishments: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press), p.127-130.

[8] Margaret Vandimer, Lethal Punishments, 125-130.

[9] Margaret Vandimer, Lethal Punishments, 129-130.

[10] Margaret Vandimer, Lethal Punishments, 130-131.

[11] Margaret Vandimer, Lethal Punishments, 131.

[12] Steven Hahn, Illiberal America: A History (New York, N.Y: W.W. Norton & Company, 2024), 216.

[13] Ann Hagedorn, Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919 (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 42.

[14] Patricia O’Toole, The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and The World He Made (New York, N.Y: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 301.

[15] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 157.

[16] Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York, N.Y: Basic Books, 2021), 135-136.

[17] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 177.

[18] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 174.

[19] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 177.

[20] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 177.

[21] Robert L. Morlan, Political Prairie Fire: The Non-Partisan League, 1915-1922 (University of Minnesota Press, 1955), 165.

[22] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 7, 95.

[23] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 157.

[24] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 97.

[25] David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press, 2004), 74; Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 100.

[26] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 82.

[27] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 156-157; Jonathan Rosenberg, Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music in America from the Great War to the Cold War (New York, N.Y: W.W.Norton, 2019).

[28] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J.Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (New York, N.Y: Viking, 2022), 56-57.

[29] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J.Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, 56.

[30] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J.Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, 62.

[31] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight, 309-310.

[32] Bud Schultz and Ruth Schultz, It Did Happen Here: Recollections of Political Repression in America (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1989), 163.

[33] Schultz, It Did Happen Here, 163.

[34] Emily Pope-Obeda, ‘‘Expelling The Foreign-Born Menace: Immigrant Dissent, The Early Deportation State, and the First American Red Scare,’’ The Journal of the Golden Age and Progressive Era,Vol.18, No.1 (January 2018), 32-55.

Featured image is J. Edgar Hoover in 1932