The Unitary Executive: A Primer for the People

The basics of a jurisprudence that, much more than originalism, defines the second Trump administration.

Through the first four months of his second term, Donald Trump has governed by aggressive assertions of executive power. Trump has relied on Article II of the Constitution to attempt to accomplish his economic and immigration policies, as well as in gutting the administrative state. Trump is a fervent believer in the unitary executive theory (UET). But what is the UET? I’ve written extensively on this issue, primarily as a critic. The goal of this essay is to provide the public with a primer on the UET.

What is the unitary executive theory?

The UET is an inference from the text of the Constitution. The first sentence of Article II grants or “vests” the executive power in “a President of the United States.” Article II also imposes a duty on the president to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” Proponents of the UET argue that, taken together, these two clauses grant the president unilateral power to fire anyone who exercises executive power.

Some supporters of the theory believe that the president also has the power to conduct foreign affairs, largely free from congressional and judicial checks. This strain of the UET was most prominent in George W. Bush’s administration, where it was used to justify mass surveillance and detainment and torture of suspected terrorists.

The UET envisions the executive branch as a pyramid, with the president at its apex. The chain of command thus flows from the president downward, toward his subordinates. The theoretical justification is small-d democratic in nature. Because the president is the only government official elected by everyone, he must be able to control policymaking by administrative agencies. The primary mechanism for doing so is the so-called removal power. The power to fire people with whom the president disagrees on policy grounds.

Congress has routinely created agencies whose leaders enjoy protection from firing. These “independent” agencies include, but are not limited to, the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commissions, the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Securities Exchange Commission. This creates a tension between the UET and independent agencies. If the president, under Article II, has unlimited power to fire officials who exercise executive power, then these independent agencies are unconstitutional.

Presidents since the Reagan Administration have largely bought into the UET, certainly for practical reasons, if not constitutional ones. Importantly, presidents have seen increasing support for the theory from the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court and the UET

The first endorsement of the UET from the Supreme Court came in a 1926 case called Myers v. United States. The case concerned Woodrow Wilson’s firing of a postmaster, Frank Myers. The legal dispute arose because an 1876 law required the advice and consent of the Senate if the president wished to fire a postmaster before their four-year term expired. In other words, the president could not remove postmasters at will.

The majority opinion, written by William Howard Taft, held that the 1876 law was unconstitutional because it infringed on the president’s removal power. Notably, Taft’s opinion made clear that civil servants could be protected from at-will removal by Congress.

Myers is one of the lodestars for supporters of the UET, but the Court cast serious doubt on the case in 1935. Humphrey’s Executor v. United States concerned Franklin Roosevelt’s attempt to fire William Humphrey, a commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission. The FTC was (and is) a multimember agency, meaning that the leader of the agency was not a single person, but a board composed of several people. The Federal Trade Commission Act insulated board members from removal except in cases of “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” President Roosevelt had removed Humphrey because he had been appointed to the FTC by Herbert Hoover. It stands to reason that Roosevelt and Humphrey had very different views on government regulation and the role of the FTC.

In a unanimous decision, the Court upheld the removal protections in the statute which meant that Roosevelt’s firing of Humphrey was unlawful. The Court reasoned that the president’s removal power did not extend to agencies like the FTC, who did not exercise executive power.

Thus was the legal landscape from 1935 to 2020. Myers stood for the idea that the president, by virtue of Article II, possessed an unlimited removal power to fire officials who exercised executive power on the president’s behalf. Humphrey’s Executor said that officials on multimember boards, who do not principally exercise executive power, can be insulated from firing by the president.

In 2020, the Court struck down the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in a case called Seila Law. Writing for a 5-4 majority, John Roberts reaffirmed the core holding of Myers while purporting to confine Humphrey’s Executor to its facts. Roberts argued that Humphrey’s Executor did not apply to the director of the CFPB because the CFPB was led by a single person, rather than a multimember board like the FTC. In a passing reference in Trump v. U.S., the Court said that the removal power is a “core constitutional power,” and that the president must have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution with regard to firings.

After Seila Law, the legal landscape looks like this: the president is vested with an implicit, unlimited power to fire subordinates (Myers), but Congress may only insulate multimember boards who do not primarily exercise executive power (Humphrey’s Executor); Seila Law reaffirmed the Court’s commitment to this framework; Trump v. U.S. says that (1) the removal power is a core executive power, and (2) the president cannot be criminally prosecuted for firing anyone who wields executive power.

Why the unitary executive?

The UET has been particularly attractive to legal and political conservatives. Donald Trump wholeheartedly believes in the theory, as do the lawyers in his administration. As detailed above, the Supreme Court has also bought into the theory—largely enshrining it into the text of the Constitution itself. The question is: why?

The UET finds its intellectual foundations in the Reagan Administration. As John Dearborn recently argued, the UET became particularly attractive as a legal argument to rein in the sprawling civil rights bureaucracy created by the Great Society. Reagan won the presidency partially on his promise to pare down government regulation, including its efforts to protect civil rights at the federal level. The ideas underpinning the UET—the power to fire bureaucrats who disagreed with the president’s policy agenda—provided a persuasive constitutional argument to utilize in bending the civil rights bureaucracy to Reagan’s will.

In the wake of Reagan’s presidency, legal scholars took to the law reviews to work the UET pure. Gary Lawson and Steven Calabresi, two members of the Reagan Administration, became some of the theory’s earliest proponents. And the idea stuck. It’s not difficult to see the appeal of the theory for presidents—governing is difficult, and if you have a legitimate constitutional argument for controlling the administrative state, one can understand why Democrats and Republicans would adopt the theory.

The problem with the UET is that it assumes a president who generally acts in good faith. By “good faith,” I mean one who believes in the rule of law and the separation of powers. The Trump Administration does not believe in those ideas. And so, the UET is ripe for abuse in the hands of a president like Trump.

Proponents of the UET claim that the theory is only about control of the administrative state, buttressed by “good government” rationales. With the second Trump presidency, we’re going to see how far the theory can stretch in practice. It appears, so far, that it stretches far beyond mere control of the bureaucracy.

Trump has incorporated the theory into his executive orders, as well as in his justifications for gutting agencies such as the National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board. It’s important to note that both the NLRB and MSPB fit the rationale of Humphrey’s Executor—multimember agencies whose board members are insulated from at-will removal. The Department of Justice has asked the Supreme Court to overrule Humphrey’s Executor, which would mean that the removal protections on members of the NLRB, FTC, MSPB, and potentially the Federal Reserve, are unconstitutional.

The Fed is the most controversial on this front. Late last month, the Court issued a two-page order asserting that the Fed “is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity” that has historical roots in the Banks of the United States in the early republic. This is a policy argument, not a legal one. And so, if the Court wants to be intellectually pure, they will have to grapple with the implications of overruling Humphrey’s Executor for the Fed.

As I have argued, the question of executive power implicates the powers of all three branches, not just the executive branch. The Court’s recent decisions represent an effort to aggrandize their own powers, as well as those of the president. The consequence is a weakening of Congress and its ability to check abuses of executive power.

In short, the first five months of Trump’s second term presents the potential to fundamentally change the nature of executive power. The UET lies at the heart of Trump’s actions thus far. The question is “how much work can the UET do?” It appears, so far, that the answer is “quite a lot.”

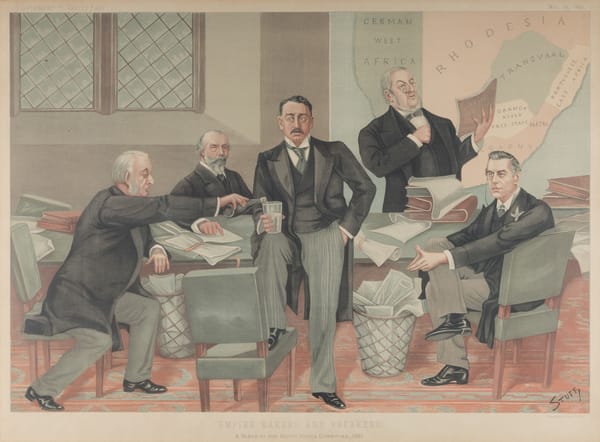

Featured image is President Reagan receiving the Tower Commission Report in the Cabinet Room