The Washington Post and the Limits of Mourning

It is time to move from grief to revival.

Drawing upon a mixture of religious law and cultural custom, Judaism sets forth a precise calendar for mourning and its conclusion. An observant Jew must be buried within one day of death, only excluding the Sabbath. Then mourners gather at the home of the bereaved family over seven days of shiva, worshipping together, supplying meals, and providing solace. For the next year, as they incrementally return to ordinary life, the closest relatives recite the memorial prayer, Kaddish, three times a day. Only on the first anniversary of a loved one’s death, in a ceremony known as an unveiling, do the survivors place a marker on the grave.

In describing this process, I do not mean to privilege Judaism’s practices. Virtually every major religion has its rules and its norms about death and grief. I just happen to be intimately familiar with my own faith’s practices. And, if you will permit me to make a leap of analogy, I believe that the interplay that Judaism establishes between grieving and reviving offers an urgent lesson for American journalism in the wake of the latest demolition of the Washington Post by Jeff Bezos and his masthead full of hit men.

As most readers of this essay already know, Post editor-in-chief Matt Murray laid off three hundred journalists from an already-depleted newsroom on February 4, wiping out the entire books and sports sections and carving deeply into the Metro and international staffs. Anyone who believes the stated plan by Murray and publisher Will Lewis to concentrate coverage on the newspaper’s core topics of politics, government, and security is a willful fool. This week’s cuts to the Post form just the most recent stage in gradual, assisted suicide, with Bezos as the Dr. Kevorkian.

The same tech mogul who seemed to be the financially struggling Post’s savior when he purchased it for $250 million in 2013 and backed Marty Baron’s courageous stint as editor during Trump 1.0 has now…well, we all know. Killed the editorial endorsing Kamala Harris for president. Banned progressive voices from the op-ed page. Censored an award-winning editorial cartoonist. Put $75 million into producing and promoting Melania. As a documentary, it is an empty pair of stilettos; as a bribe, it certainly has worked. The recent gutting of the Post staff very fittingly came within days of the film’s premiere.

Considering this sequence of assaults on a legendary newspaper, it is completely understandable, and also necessary for posterity, that Post expatriates such as Baron, Ruth Marcus, and Ashley Parker have taken to their current journalism platforms and social media accounts to bewail the fate of a newspaper they loved. And, yes, wailing is the operative verb. The ongoing destruction of the Post, part of the MAGA movement’s larger attack on independent journalism and indeed democracy itself, deserves sackcloth and ashes.

Which brings me back to the Jewish way of mourning. Though any death ends a life, not every death is identical in its emotional toll. I speak from personal experience. Losing my father at age 89—lucid until the end, listening to his favorite operas on a CD player while in hospice –let me feel grateful for his long life and his easy leave-taking. Losing my mother at age 50—already ravaged by breast cancer, finished off when a hospital intern botched a lung-tap—filled me with anguish for a life cut off with its greatest dreams unrealized. You can pretty much guess which kind of death I believe that the Washington Post suffered.

But those of us who care passionately about journalism and democracy must balance our mourning with the critical, pressing work that needs doing. We can keep saying our version of Kaddish, we can select the wording and design for the headstone to be laid. Meanwhile we must find another way for the legacy of the Post to be perpetuated. It is well-deserved for the stars of the Post to depart on their own terms, whether being hired by the Atlantic, New Yorker, and New York Times, or leveraging their stellar reputations to launch a Substack such as The Contrarian. A world-class news organization, though, amounts to more than its stars. The open question is what happens to hundreds of other immensely talented Post staffers (including those who left or were laid off before this latest round of blood-letting) and of the news coverage they were integral to providing.

The obvious answer sits not so many miles north on Route 95 in the form of the Baltimore Banner. If you don’t live in or near Baltimore, then you may only know of its legacy newspaper, the Sun, from its slightly fictionalized treatment in the cable series The Wire, created by one of the newsroom’s illustrious alumni, David Simon. For much of its lifespan, the Sun was not only the paper of record for Baltimore, excelling at holding the city’s extravagantly corrupt politicians to account, but it staffed a major bureau in Washington and several posts abroad.

During the digital era, the Sun suffered from the same collapse of revenue as did virtually every newspaper in America, with classified ads migrating to the free site Craigslist and display ads to aggregators and social-media sites that could precisely target consumers. In addition to the structural challenges, the Sun endured a second all-too-common plague of 21st-century journalism: being bought in 2021 by the hedge fund Alden Global Capital, an outfit notorious for stripping and selling off pieces of its media properties like a chop shop yanking apart a stolen car. Bad became worse in January 2024, when the Sinclair Broadcast Group bought the Sun. Though led by a Baltimore native, David Smith, Sinclair was already infamous for pushing a right-wing agenda onto the 200 television stations it owns.

Here is how those who mourn the slow-motion death of the Post can put grief into generative action. At the same time Sinclair was pursuing the Sun, a group of current staffers and a wealthy local businessman had been trying to put together a competing offer. Having lost out in the bidding war, this team did not slink away in defeat. Their angel investor, a hotelier named Stuart Bainum, put $50 million into forming a nonprofit corporation that would operate a start-up news organization, the Baltimore Banner. Launched in 2022 with an annual budget of $15 million, the Banner matched and then surpassed the size of the Sun’s newsroom, poaching some of its most talented veterans.

By late 2025, the Banner boasted a newsroom staff of 95, 69,000 subscribers, and $13.3 million in revenue. Though not yet profitable, income from the main pathways of philanthropy, subscriptions, and advertising has been steadily growing over the paper’s short history. Last spring, the Banner won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the fentanyl crisis in Baltimore.

In its achievements, the Banner has proven both exceptional and typical. It typifies the boom in non-profit journalism. The Institute for Nonprofit News counts 500 member organizations. Some nonprofits, like the Banner, Texas Tribune, and Berkeleyside, define their mandate geographically, akin to the diminished or defunct local papers they are outpacing. Other nonprofits orient themselves by specialty—investigative reporting for ProPublica, criminal-justice issues for the Marshall Project, education for Chalkbeat. In various proportions, most nonprofit news organizations rely on a mixture of donors, subscribers, and advertisers.

The essential truth underlying the entire nonprofit news industry—the truth that anyone bemoaning the fate of the Post must comprehend and act upon—is that two venerable models of new-organization ownership are no longer broadly viable, or even advisable. One, as I noted earlier in this essay, is the revenue stream based largely on classified and display ads, with paid-circulation numbers mostly important for attracting the advertisers. The digital revolution, with its micro-targeted ads and free content, has destroyed that model.

The second model relies on the public-spirited family or individual, willing to take a smallish profit or absorb a modest loss in order to serve the citizenry with professional, responsible journalism. Yes, some examples of that model persist—the Sulzberger family for the New York Times, Michael Bloomberg for his eponymous news organization. A billionaire whom you may not know of, Glen Taylor, rescued the Minnesota Star Tribune (then with Minneapolis in its title) from a fiscal death cycle when he bought it in 2014, and proceeded to rapidly increase newsroom hiring and move the staff into a swanky tower downtown. The exceptional coverage that the Star Tribune has provided during the ICE siege attests to the wisdom of pouring money into, rather draining it out of, a news organization.

Only a naif, however, would put faith into cloning the next Glen Taylor. Jeff Bezos looked like a far wealthier, far more influential version of Taylor back when he bought the Post and coined its slogan, “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” A dozen years later, Bezos is betraying his own better angels, sitting upon a net worth of $250 billion while the Post costs him an annual loss of just $100 million. That loss, though, serves another purpose. It supplies the excuse for eviscerating the news staff and news product, all but ensuring that subscription numbers will plummet even more. The future of the Post under Bezos looks to me a lot like the future of another damaged legacy institution, CBS News, under David Ellison and Bari Weiss. The audience will keep shrinking, even as the editorial slant tilts into appeasing the king.

We who admired and depended upon the Post cannot just lament. What would it mean to have a top-flight editor like Marty Baron or Kevin Merida to come out of retirement to helm a nonprofit competitor? How many excellent reporters, editors, photographers, and designers would gladly join? (And don’t forget to recruit from the former and current staffers of USA Today, located just across the Potomac from D.C.) How great would be the attraction of this journalistic team and its mission to mega-philanthropists like Melinda French Gates and Laurene Powell Jobs with their demonstrable interest in nonprofit journalism? Perhaps Mackenzie Scott, Bezos’s ex, could throw in some of her millions, for the sake of both the Fourth Estate and Schadenfreude.

And then—this is essential—don’t get complacent. Don’t assume that Mommy or Daddy Warbucks will always be ready to write another check. Develop your donors and subscribers and advertisers. Build up your financial base for self-sufficiency. It surely can be done. It has been done. National Public Radio has been doing it for decades. That’s why NPR survived Congress shutting down the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and why many member stations saw their listeners’ donations fill or even exceed the gap.

If we do all those things, we can still mourn the Post that once was, the Post of Ben Bradlee, Woodward and Bernstein, George Will, Ann Telnaes, Jennifer Rubin, Eugene Robinson, so many other luminaries. But then we will be able to leave the gravesite and go home and use our paid membership to spend time on the website of a nonprofit newsroom in Washington that’s breaking scoops every day. We just need a name for it. Somehow the word Independent keeps coming to my mind.

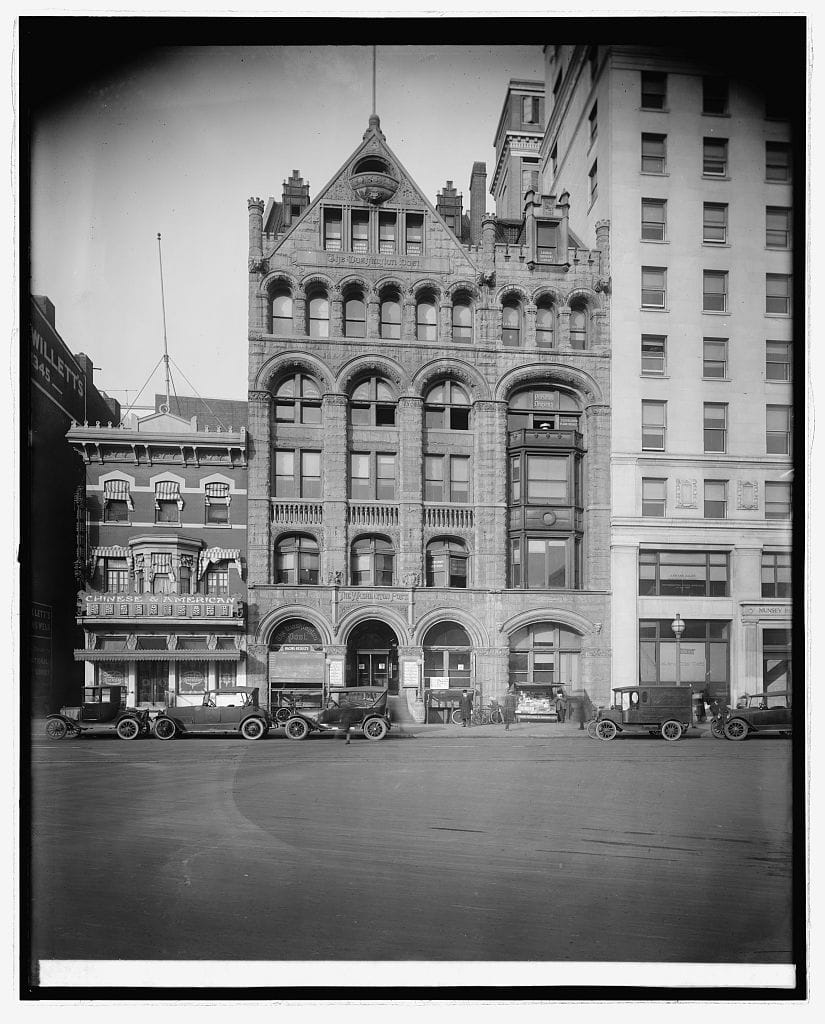

Featured image is the old Washington Post building