There Are No Simple Answers to International Relations

Everyone who has ever approached international relations with a formula has always overreached and oversimplified.

One of Bertrand Russell’s great insights, now a popular liberal refrain, is that movements always go too far. Even the best ideas must be adaptable to events or risk consequences that run counter to the intentions of the original theorists. Theories often fall victim to their own success; once-fluid solutions to contemporary problems become solidified over time, leading to dogmatism. Nowhere is theoretical overreach more dangerous than in the field of international relations.

So often in the past, the very theories designed to minimize the likelihood of war have themselves become part of justifications for war. Theories become seductive to their practitioners, blinding them to the failings occurring at their margins. Containing a large element of truth is simply not good enough for a theory to navigate the stormy seas of geopolitics. Most illustrative of this point is the period before the Great War (1899–1914). Despite being an extremely fertile time for new theories of international relations and the avoidance of war, so often, the flaws in these theories were exposed by the actions of malign actors and changes in the geopolitical landscape.

Liberal pacifists learned the dangers of excessive idealism all too well. The whole ethos behind the Hague Peace Conference 1899, designed to maintain the balance of power and curb the excesses of imperial violence, was ineffectual in the face of the aggressive German armament program in the following decade. The hard-won gains at the Hague Conference only served to bolster the casus belli in 1914. (Germany was undeniably in breach of international law, both in the manner and the mere fact of their incursion into Belgium.) Ultimately, many pacifists were faced with the stark choice of surrendering their basic commitment to nonviolence or their support for the international rule of law they had worked so tirelessly towards. During the Great War itself, the Movement lost any remaining control of the key terms as the government propaganda campaign rebranded the slaughter as a ‘War for Peace’.

Feminist theories of pacifism fell into similar logical traps, ending up justifying the wars they initially opposed. Just a month before the outbreak of hostilities, on 19 June 1914, Christabel Pankhurst wrote an editorial for ‘The Suffragette’ entitled ‘How Men Fight’. Christabel made a Freudian-sounding argument about the need to restrain base male instincts. ‘Government by men only… is responsible for this insanity, this murder-suicide of modern warfare. The unrestrained and anti-social pugnacity of the male must be restrained by the power of enfranchised women’.

Ultimately though, by 24 October 1914, Christabel was using identical feminist arguments to justify British involvement in the War: ‘When the women of the world are enfranchised then indeed we may hope to see the reign of universal peace. But so long as you have one nation which, like Germany, boasts that it is a male nation, a country in which the councils of women emphatically do not prevail, then you will have the peace-loving nations always on the defensive, always compelled to be arming and to meet the armed aggression of that too much male-governed country in which women are not free’. Indeed, for Christabel, a German victory would be a ‘disastrous blow’ to the international women’s movement since Germany was an unashamedly ‘male nation’.

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), the Russian nobleman and novelist, was the rallying figure behind the philosophical case of nonviolence. The idea that Christianity demanded nonviolence was not a new one. Christian nonviolence already had many adherents among the Mennonites in central Europe, the Quakers in Britain and the United States, and the Russian Doukhobors. But Tolstoy reinvigorated the position at the end of the nineteenth century. Exploiting his renown as a novelist, Tolstoy ferociously promoted absolute pacifism. Central to his thought was Matthew’s injunction of ‘resist not evil’. Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894) became a classic text for peace advocates the world over, providing inspiration to the young Hindu Mohandas Gandhi. Tolstoy’s theory of nonviolence held that the only long-term guarantor of peace was that populations would refuse to fight.

The problems with Tolstoy’s theory were plain even to his pacifist contemporaries. British peace activist George Perris greatly admired Tolstoy, but could not dispel the troubling realisation that failing to resist evil would ultimately encourage evil. That is to say, there are evils that are worse than the just application of violence. For many people, the Holocaust put pay to the Christian notion of the essential goodness of Man: Palpably, mechanised genocide made no consideration for the non-resistance of those subjected to it.

Arguing from a sociological standpoint, the Polish banker Ivan Bloch (1836–1902) sought to demonstrate that a general war was unwinnable and would wreak disaster on all the combatants. Bloch famously went on to predict, with great precision, the trench warfare between the Great Powers that would result in stalemate, economic ruin and ultimately socialist revolution. War was therefore ‘impossible’ for the most grounded reasons, or so Bloch claimed. Bloch was right about the result of the Great War, especially in relation to Russia, which had a Bolshevik revolution in 1917. He overestimated, however, how much of a deterrent this would be to the warring nations.

The Russian Jacques Novicow (1849–1912) followed a similarly sociological approach, although he targeted academics rather than statesmen. Novicow published works rejecting certain social applications of Darwinism, most directly in La Critique du Darwinisme Social (1910). Social Darwinism linked the struggle among species for survival with the struggle among nations for supremacy. This approach had advocates among leading sociologists of the time, including Lester Ward, Herbert Spencer, Ludwig Gumplowicz and Gustav Ratzenhofer. For Novicow, the unreflective extension of Darwin’s theory into sociology was based on a number of misunderstandings. While he accepted that the struggle for existence was the all-important factor in social evolution, in the case of humans, this struggle was marked by physiological, economic, political and intellectual contests that were absent from other animal species. Moreover, Novicow held that it was the intellectual struggle that was increasingly the most important agent of social change.

However, the trend for positivism in sociology disadvantaged pacifist sociologists since it was hard to deny that competition existed between species everywhere in nature, as shown by vast amounts of empirical research. Also, it remains to be seen if humanity is indeed on a progressive linear course in which intellectual contests will be of greater consequence than military ones.

The economic argument against war was advanced from both socialist and liberal sources. In Imperialism: A Study (1902), Hobson argued that the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) and the Scramble for Africa generally, had been economically detrimental to all but a handful of influential investors and arms manufacturers. These investors and other sectional interests were able to promote their war aims through their control of the press, convincing politicians and citizens to pursue the unprofitable business of imperial expansion. Investors could not find adequately profitable investment opportunities domestically due to under-consumption in the British economy and this created a surplus of investment capital. This surplus capital they sought to engage in more profitable but riskier fields of investment in the tropics.

These tropical areas were then seized at the behest of the investors as this was the only reliable method of ensuring the safety and maximizing the profits from these new fields of investment. Thus, the pressure to find new profitable fields of investment abroad was primarily to blame for the Anglo-Boer War. The way to break this cycle was to redistribute surplus capital to the poor, who would then increase their spending thus solving the problem of under-consumption. Over the longer term this would reduce the incentive to expand the empire and Britain’s reliance on exports, as well as raising domestic living standards. For Hobson, imperial expansion was not in the economic interests of the majority and certainly not in the interests of the working classes, the people most susceptible to jingoism by his reckoning.

Besides the role of shady financiers in engineering wars of imperialism, Hobson also liked to generalise about the dangers of protectionism and the benefits of Free Trade. The seduction of his own theory blinded Hobson to the onset of the Great War, an event that took him completely by surprise. According to his theory, the cooperation of international finance capital should have prevented a major conflagration between the great powers. Consequently, Hobson tended to dismiss any concerns about the military ambitions of Germany as ‘Teutophobic’ in The German Panic (1913) (referring to the irrational fear of Germans).

Norman Angell’s economic arguments in The Great Illusion (1909) continued Hobson’s objections to the economic rationality of conquest, but Angell argued from a liberal perspective reminiscent of Richard Cobden. He claimed that European economies were now so interconnected that economies would benefit from nurturing free trade with their neighbours rather than attempting to invade them. Advanced economies were dependent on credit and commercial contract. Even if an invasion was to be militarily successful, property rights would have to be respected and existing contracts honoured. To act otherwise would cause an economic collapse that would be contagious to the economy of the invader. But given that property rights would have to be respected, this seriously undermined the economic rationale for invading in the first place.

The potential risks also had to be considered, that the war might be lost, or that an insurgency might make a long-term military occupation necessary. While Hobson had set his sights on British jingoism and ‘stock-jobbing’ investors, Angell was seeking to convince Germans that a war path was economically imprudent, and to temper British fears that this was the probable course of events. This shift of emphasis was indicative of the changing threats to international peace by 1909. We see this in Angell’s choice of examples. He argued that Germans had not become richer as a result of the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine and they would not benefit from raiding the Bank of England for the same reason - it would be disastrous for Germany to destroy the economy it would be forced to absorb.

Even if Angell was correct in the dubious claim that conquest was without economic advantages, his theory still overemphasized rationality in politics. Wars often have completely irrational causes. As such, Angell’s lecture tours in Germany seemed largely to have fallen on deaf ears.

The failure of these idealists in mounting a credible alternative to war in 1914, led many to draw the lesson that idealism itself was at fault. The historian Edward Hallett Carr (1892–1982) argued as much in The Twenty Years’ Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations (1939). He drew a line between “utopian” liberal idealists and the more pragmatic realists. Carr rejected the idealists’ claim to moral universalism. Indeed, he argued that notions like “the harmony of interests”—the idea that nations could be persuaded to cooperate according to shared goals and values—were evoked by privileged liberal elites to maintain and justify their dominance.

Realism was a fixture during the Cold War and has recently resurged with the return of bipolar China-US competition and the backdrop of the Ukraine war. The theory often holds that nation-states are incorrigible, that wars are a fact of life, and that countries will resort to anything to obtain the upper hand over their adversaries, including violence. This pessimistic tradition is separated from outright militarism by a dread of warfare and an awareness of the unexpected risks it can throw up. Unfortunately, realism contains the same tendency towards dogmatism that the discussed idealist theories involved.

Although a subtle practitioner of realism, the academic Patrick Porter wrote recently that a performative deference would be the pragmatic way for Zelenskyy to have dealt with President Trump. Porter claimed that Zelenskyy “could have emulated British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who grasped the hard truth that the Trump court expects lesser powers to behave like grateful, deferential supplicants. Instead, he put being right above being effective”. In this recommendation, Porter seems to be quietly seconding Vance’s odious suggestion that Ukraine “doesn’t have the cards” and should act accordingly. Expecting deference from countries with smaller militaries has become the calling card of the current geopolitical climate.

The Russian Ambassador to Indonesia bluntly told Australia that they “did not have the cards” to protest Russian military cooperation with Indonesia. Porter might be right that the prudent, indeed moral, path in both these cases was for the smaller military power to defer to the larger one, (at least for appearances sake). However, I fear for the world in which brute power is met with automatic accommodation. Indeed, the line between performative and substantive accommodation might prove to be paper thin. Counseling this kind of preloaded servility is, to my mind, a symptom of theoretical overreach.

Certainly, we need to be mindful of military realities, but morality matters too. Without a strong perception of justice underlying our alliances, they become shaky marriages of convenience. Indeed, E. H. Carr warned about the overzealous realism of “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” at the end of The Twenty Years’ Crisis: “If… it is utopian to ignore the element of power, it is an unreal kind of realism which ignores the element of morality in any world order. Just as within the state every government, though it needs power as a basis of its authority, also needs the moral basis of the consent of the governed, so an international order cannot be based on power alone, for the simple reason that mankind will in the long run always revolt against naked power. Any international order presupposes a substantial measure of general consent.” In a world increasingly marked by power contests, we would do well to remember that morality cannot be so easily brushed aside.

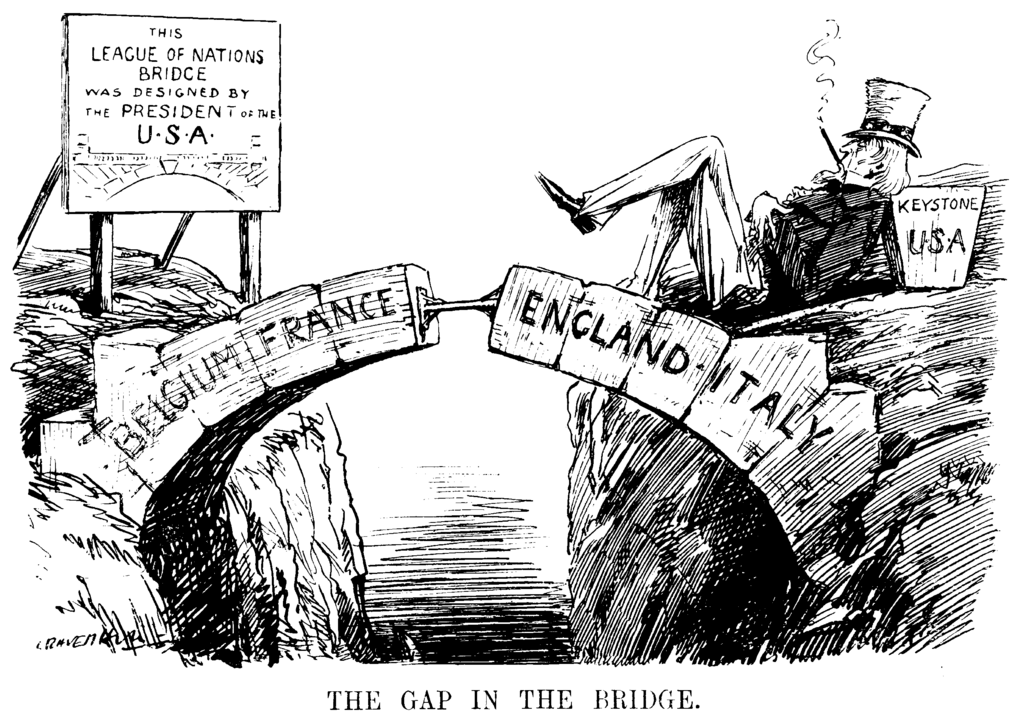

Featured image is The Gap in the Bridge, by P. Raffo