To My Students on the Anniversary of January 6

The political violence of the Trump era is all today's teenagers have ever known.

For over a decade now, I’ve been a high school world history teacher, which means that I am acutely aware of time’s passage—both historically and for the age groups I teach. On November 8, 2016, my current students were between the ages of 3 and 7. On January 6th, 2021, they were between the ages of 9 and 13. This year, they’re turning something between 15 and 18. Practically all of them have very little memory of a time before this political era dominated by Trumpism and its open racism, authoritarianism, and obliteration—figuratively and literally—of political norms. No example of all this is clearer than January 6, when the Trumpist politics of victimhood and violence erupted at the United States Capitol in the guise of a popular movement reflecting the will of the people. It’s been five years since then, and a better future for my students is in doubt.

I’ve been teaching for a long time. This is my 17th year in a classroom. I’ve learned that history never really repeats itself, but studying history can reveal patterns and “possible worlds,” as historians Matthew Gabriele and David Perry have recently reminded me in their new survey of the Middle Ages. I marvel at my students’ ability to make connections between ancient and modern patterns of power in my Roman history seminar. Our training as historians helps us examine historical patterns to make better sense of our current moment—and to illuminate possible worlds.

So, I find myself thinking often about an historical example of a Roman election that set dangerous precedents for the future: the events of 133 BCE deepened factions, normalized political violence, thrust the politics of victimhood into the mainstream, and paved the way to autocratic rule. In both 133 BCE and 2021, the power classes who stoked electoral violence made the same argument: that their violence against enemies of the people was inherently justified. Within decades, Romans lived under various forms of autocracy. But I think we can do better for my students’ generation, because we’re capable of popular movements that weren’t available to ancient people.

Since the Roman Empire is my Roman Empire (but not in a weird way), I’m thinking of 133 BCE’s election featuring the tribune Tiberius Gracchus attempting a second consecutive term, a major violation of the unwritten rules of Roman politics at the time. Now, I’m not here to compare Trump to Tiberius (which would be a bizarre argument, not least because Tiberius appears to have actually cared about his constituents), and besides, the dictator Sulla (d. 78 BCE) is probably closer to the mark.

But Tiberius had done a relatively new thing in Roman politics: circumventing the Senate, he hit the campaign trail, submitting his policy ideas directly to the people. Despite his wealthy, aristocratic background, Tiberius sought to be elected tribune of the plebeians, the lower class of Roman citizens opposite the smaller patrician class. In our own era of perpetual and exhausting campaign cycles, all this sounds pretty tame, but it went against Roman custom.

Tiberius’ politics were relatively progressive: his proposed policies would later become standard in Roman society. In our terms, he sought to create a Roman “middle class” by capping the elite’s ability to exploit public land and redistributing the surplus to various dispossessed groups. But Tiberius’ powerful enemies in the Senate resented his politics in part because they themselves might see their wealth diminished.

Opposition to Tiberius was too robust to get anything done quickly. As his term as tribune came to a close, Tiberius announced to his loyal following that he was going to run again, a violation of ancient custom—what Romans referred to as the mos maiorum—during this era of Roman politics. It seemed worth the risk: to his supporters, Tiberius was a popular champion of their rights; to his enemies, he was an aspiring tyrant seeking personal loyalty of the masses while flaunting the rules of the game at every turn. Tiberius’ recent ouster of fellow tribune Marcus Octavius was a clear violation of the mos maiorum and his campaign for reelection was the last straw.

On the day of the vote, Tiberius’ supporters arrived to show their support for him. The faction opposing him did the same. We might want to imagine a festive atmosphere, full of possibility, on edge. After heated disagreement over how the vote should be conducted and a failed attempt to stop the count of votes, Tiberius’ enemies left the electoral assembly, instigated a riot, returned to the assembly armed with clubs and broken chair legs, and beat Tiberius to death along with some 300 of his supporters. Their bodies, along with any prospect of compromise, were tossed into the Tiber River.

For Tiberius’ opponents this bloody day was a righteous uprising against an aspiring king. The Senate, as representatives of the people of Rome, saw Tiberius’ death as the will of the people. Yet this was a group of people violently storming the seat of government because they didn’t get their way.

This brutal day in Roman history set dangerous precedents for society in following decades: political factions deepened, violence frequently replaced debate, Roman elites embraced the politics of anger and victimhood when exacting revenge on their political opponents, and tolerance for the politics of anger grew to accommodate the concept of autocratic, authoritarian rule.

Both January 6th and the riots against Tiberius Gracchus and his supporters were orchestrated to appear as outbursts of endlessly justifiable popular rage against the state’s enemies. As Jamelle Bouie and others have noted, Trump's power is based on a widespread belief that he is a “sovereign avatar … imbued with the will of the people.” In Tiberius’s case, that “sovereign avatar” was a conservative, reactionary senatorial elite.

But there’s another reason some of this feels familiar: it’s pretty much all my students have ever known. Trump’s first term was marked by a crushing of political norms and a normalization of political violence; “very fine people” rehearsed this in Charlottesville in 2017. And in the first year of his second term Trump has declared war on American cities, citizens, and clergy and executed people on boats in the Caribbean and Pacific.

As a teacher I’m trying to instill in my students, whom I care so deeply for, a sense of civic virtue, of care for their communities and classmates. I’m trying to teach them that the truth matters. And yet, they are coming of age in the shadow of a regime that openly scoffs at such notions, that has nothing but disdain for living an ethical life. Our depraved and scandalous government breaks our own community's rules at every turn, with impunity.

I want my students to understand that, while stories like this from the ancient world might feel familiar and thus inevitable, we shouldn’t treat them as normal. It should not be normal for them to hear a presidential candidate calling January 6 a “day of love” as part of a seemingly endless barrage of threats against his political enemies. Campaigning and following through on a promise to violently deport millions of immigrants who are “poisoning the blood” of the country is immediately reminiscent of concentration camp history. I don’t want this to be normal for them. I want it to shock them. But if history shows us possible futures, I want them to have what it takes to recognize patterns of violent rhetoric and to effect change starting with their own communities.

When a society allows fear, hate, and fabricated victimhood to dominate their politics, it has lost something essential. And for now I’m choosing to believe we haven’t lost that essential something, because I see it in my community every single day: we care, we donate, we show up at protests and for each other, we persevere. There are good people everywhere. I hope my students can find them, stay close, and cultivate everything that’s best about our country in those communities. That’s a popular movement worth cherishing. That’s the will of the people.

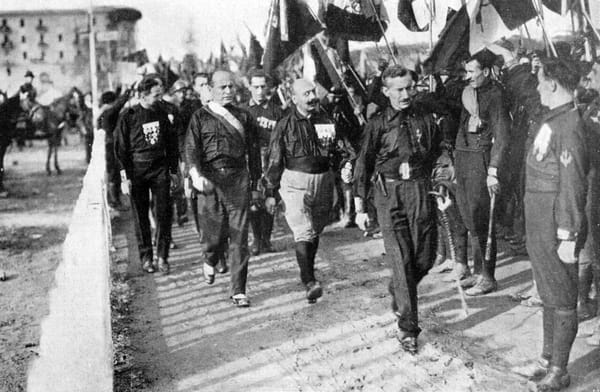

Featured image is "Death of Tiberius Gracchus," Lodovico Pogliaghi 1890.