Towards a Green Liberalism

Former UK Prime Minister Theresa May quipped that “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere” at a Conservative Party conference in the fall of 2016. British voters had just narrowly voted to leave the European Union and the United States had yet to elect Donald Trump to the presidency. But Ms. May’s comments highlight a common criticism of contemporary liberalism. In this view, liberals are too closely associated with cosmopolitanism and technocratic fixes for public problems. Meanwhile, those on the green left, such as British economist Kate Raworth, insist that environmental protection requires a decoupling from economic growth. In this view, capitalism is the primary driver behind environmental degradation and looming climate catastrophe. This is plainly preposterous, as lingering natural devastation in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union can attest. Many on the right and left charge that leaders and political movements need to focus on the common man within a particular place and that liberalism simply isn’t up to the challenge.

This diagnosis is overly simplistic and fails to account for liberalism’s proven ability to reinvent itself in response to changing times and attitudes, in addition to its flexibility with regards to problem-solving. However, it does indict the complacency of contemporary liberalism and its failure to adequately engage with the public. Past complacency and institutional rot has led to renewal and reform within the liberal tradition, leading to the Progressive Movement of the early 20th century, the New Deal of the 1930s, and the Great Society of the 1960s.

Situated in the wider liberal tradition, green liberalism offers one such opportunity for renewal. Green liberalism is rooted in a sense of place, engaging communities’ immediate concerns for the wellbeing of themselves, their neighbors, and the future of their communities. Climate change and environmental protection, despite assertions to the contrary, are not the preserve of the coastal elite. Flooding in the Midwest, more severe hurricanes in the Gulf, and severe droughts in the mountainous West indicate that the threat of climate change is real now and these warnings will only grow more dire with time. Green liberalism offers an opportunity for the revival of civic nationalism, when individuals and communities come together in pursuit of a common societal goal. Those who lean right can champion the conservation of natural resources and the homeland, while their counterparts on the left strive for progress on environmental justice and equitable growth. All have a stake in preventing climate catastrophe and green liberalism offers a way forward.

Climate change and environmental protection are rapidly ascending the list of Americans’ policy priorities. A recent study by the Pew Research Center indicated that 64 percent of US adults say that the environment should be a “top priority” for the the president and Congress, up from 44 percent in 2002. This polling suggests that climate action has the potential to bring together a wide coalition under the liberal tent, like so many other issues have in the past.

Other liberal parties and movements have been quick to incorporate green politics and environmental protection into their governing philosophy, particularly in Scandinavia and German-speaking Europe. The Norwegian Liberal Party has championed environmental causes since the 1970s and Sweden’s Centre Party describes its ideal as “social-liberal and green, with a strong emphasis on sustainability and decentralization.”

In Switzerland, members of the Green Party uncomfortable with a leftist political platform formed the Green Liberal Party, which won 16 out of 200 seats in the last election, an increase of 9 seats from the previous election. The Swiss Green Liberals, like their counterparts in Scandinavia, focus on the decentralization of power to local stakeholders, shifting of tax burdens from income to pollution and conspicuous consumption, and creating a robust clean energy market. Unlike the conventional Green parties in their home countries, they are broadly supportive of the market economy, skeptical of large tax increases, and somewhat less supportive of the labor movement.

Further north, the German Greens are perhaps the world’s most successful example of green politics. Split between more conventionally leftist “Fundis” and more liberal “Realos”, the party has made significant gains in state parliaments and is eagerly eyeing the opportunity to govern following the upcoming departure of Chancellor Angela Merkel. The party’s current leadership is fairly described as pragmatic and liberal, seeking an “ecological tax shift” away from labor income towards polluting industries and activity combined with a strongly liberal approach on engagement within the European Union and a welcoming policy towards migrants.

In contrast, American liberal and progressive movements have had an awkward relationship with green politics. In 2019, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey introduced the Green New Deal resolution, calling for the complete decarbonization of the US economy by 2030, leading to mockery from conservatives and unease from the mainstream of the Democratic party. Most contenders for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination released comprehensive and ambitious climate plans but party leadership has been reticent to align itself with the environmental movement. The last major effort to pass comprehensive climate legislation occurred in 2009, when the American Clean Energy and Security Act passed the House of Representatives before sputtering out in the face of a hesitant Democratic majority in the Senate.

Meanwhile, Republican leadership has largely declined to acknowledge the serious threat of climate change, instead offering up plans to plant billions of trees and expand tax credits for carbon capture and sequestration. And the US Green Party, while disadvantaged by America’s two-party politics and electoral system, has doubled down on leftist politics, with its presumptive 2020 nominee highlighting an “Ecosocialist Green New Deal” as the centerpiece of his policy platform.

That leaves a significant gap in American politics for an ecological movement grounded in liberalism, much as other political movements are grounded in the language and traditions of liberalism. This synthesis of liberalism and green politics is often referred to as “green liberalism”, “eco-liberalism”, or “liberal ecology.” Marcel Wissenburg coined the term “green liberalism” in his 1998 book of the same name to describe a variant of liberalism shooting out of the growing environmental movement. He characterized contemporary green parties and political associations as inadequate due to their hostility towards liberal democracy and penchant for revolutionary rhetoric. Instead, he argued, liberal democracy is fully compatible with green politics, but the two do not necessarily require each other. That is to say, a society can be liberal and democratic without taking significant steps to ensure ecological sustainability.

While some have decried green politics as befitting only the urbane elite and technocrats, green liberals in Europe have shown that concerns about climate change and a commitment to environmental justice are entirely compatible with movements that also reach out to rural dwellers, cultural moderates, and the like. Sweden’s Centre Party campaigns call for an earthy liberalism and the party has historically been successful among farmers. Meanwhile, the German Greens made huge gains in heavily Catholic Bavaria, with candidates campaigning in traditional dress.

This is not another in the long list of tired calls for a new party. It is, however, an acknowledgment that Anglo-American liberalism has an inadequate relationship with green politics. It’s time to cultivate a new branch within the broader liberal tradition. Green liberals have invaluable contributions to make to the liberal movement and fresh, new ideas that deserve to reach a broader audience. We owe it to ourselves to make space for green liberalism.

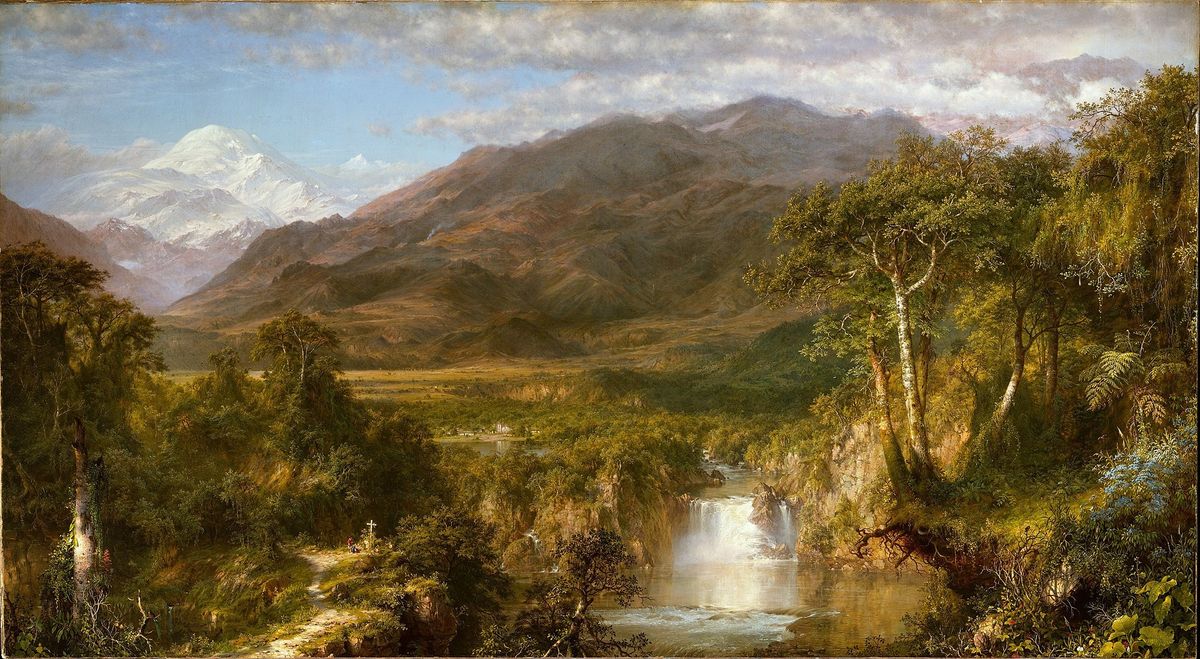

Featured image is Heart of the Andes, by Frederic Edwin Church