Towards an End of the Sanction Regime

“The Great Era of Sanction Diplomacy” is nothing more than a ruse. The extreme use of sanctions is not diplomacy at all, though they begin with diplomats, include multinational agreements and negotiations, and ostensibly seeks to avoid the death that is wrought by conventional warfare. Rather, sanctions are, like conventional warfare, acts of violence, no matter how they are dressed up to the contrary. The act of withholding resources or goods from a nation or peoples always diminishes the greater society when targeted at a nation, and is never effective at hindering oligarchs or the powerful of any given nation or state. Unfortunately, President Biden seems to be yet another in a line of presidents who have missed an opportunity to reduce our dependence on sanctions as a diplomatic tool.

Sanctions remain a key threat and tool for this administration, although not the only one they threaten, and this can be seen in a few different instances that span its first year. While it is not surprising that Joe Biden should see fit to impose sanctions against certain nations, such as North Korea, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Belarus and Ethiopia, it is more interesting that he would have kept sanctions, and actually increased them, regarding nations like Cuba, as well as Iran. While both of the aforementioned nations have civil liberties issues, to put it mildly, each relationship had been trending in more positive directions before the wholly counterproductive foreign policy campaign that was utilized by the Trump administration.

Joe Biden should understand this intimately considering that he was a part of the administration that made such substantial, diplomatic innovations like the Iranian Nuclear Deal, the further diplomatic and cultural progress with Cuba, as well as greater, improved bonds with Vietnam; these developments are the fruits of actual diplomatic efforts, and not the diplomatic dead-end that we might call the sanctioning-first-submission-based outlook of the previous and past presidential administrations. While returning to sanctions is often included as a potential recourse for breaking these agreements, it remains impossible to extricate ourselves entirely from the habit of sanctioning without creating and ensuring mutually positive avenues beyond them and the need for their use.

For to be sure, there must always be a diplomatic way forward that is conciliary and constructive for the aggrieved parties, instead of simply punitive. The threat of sanctions, even in those treaties designed to remove sanctions or to normalize or improve diplomatic, economic or cultural bonds, risk further estranging the US however, as the Iranian Nuclear Deal’s fallout acutely demonstrated; when the US broke the agreement under the administration of Donald Trump, an innovation that is unlikely to have been imagined as the crafters of it put it all together, Iran had no actual recourse relative to that which America was capable of afflicting upon Iran. When the US left and said Iran had broken the deal, it has since been Iran that has borne the brunt of the choice of another nation.

No, it is, on one hand, a collective united nature that must work to apply pressure to recalcitrant nations when action of a disagreeable nature might otherwise have to be exerted, such as through economic or military recourse. The push must always be towards counsel and discussion instead of towards decrees or sanctions that injure other parties and have no mutually constructive ends. Yet on the other, each nation must be able to truly trust in the resolve and united timbre of each cooperating portion which creates the union in the first place. When one legion of the front does not operate as do the others, the gaps it creates can be as devastating to the entire body as to the one portion. These ideas, and not the actions or beliefs of the most recent president, should be Biden’s models moving forward.

If the current president found it frustrating to see the work that the administration that he was vice president for undermined by the 45th president, he hasn’t acted like it. Joe Biden has not spent very much time working to correct the foreign policy blunders that the Trump administration made during its four years in power, at least in many instances. The great exception to this is, however, contentious, uncomfortable and, somehow, promising as well. While the current negotiations in Vienna are meant to work towards the recreation of the historic Iranian Nuclear Deal, or JCPOA, for today, a mixture of great skepticism and budding optimism exists regarding the possibility of those innovations being achievable as well, both within the United States, as well as in Tehran.

The decision made by Donald Trump in 2018 is still reverberating across the world and in Iranian domestic politics in particular. Now in power is the hardliner principlist President Ebrahim Raisi, who will surely take over in the event of the current Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s death. Reports from the negotiations have painted a difficult picture regarding a circumstance that, if a less caustic diplomacy had been practiced, and sanction warfare abandoned, would be now unthinkable. If Joe Biden can secure a deal with Iran, of which would be positive, it will most certainly be one that reflects circumstances vis-a-vis Iran as they are today, and not as they were when the Obama administration created the original agreement with Hassan Rouhani. Sanctions, meanwhile, the vehicle that has brought us to this current juncture, are cruel, have not worked, will not work, and the time for their application has passed.

Given these facts, one must ask whether there is not a better way for all of this? Should we not expect a better way to fix international circumstances, regional disputes, and squabbles between polities and their people? And how does any one polity achieve any and/or all of this, if it is indeed the way to create a better, more cooperative and more functional world?

The old liberal hope

History can be a guide in answering these questions. The signing of the JCPOA was not the first time that the United States, as a country, seemed headed in positive, mutual and international constructive direction; Franklin Delano Roosevelt famously began a process that could have led to a diminution of economic warfare and the ushering in of an age of free trade and open diplomacy. His recognition of the Soviet Union, commitment to the Good Neighbor policy in Latin America, and pressure on Great Britain to sign the Atlantic Charter renouncing imperial trade zones were all promising moves towards a more open world.

These ideas were continuations of foreign policy concepts and ideas championed by the man that FDR had worked under during the 1910s, Woodrow Wilson, as well as men who shared his vision of international cooperation and democracy. In the years succeeding the First World War, great American foreign policy intellectuals like Edwin Borchard, and Norman Thomas, as well as the Canadian James Shotwell, had envisioned a body like Wilson’s League of Nations could utilize the collective energy and determination of the international community to slow down or even prevent the nefarious ambitions of leaders and rogue polities, without the need to stoop to the base military conflict of which they had only so recently escaped from. But the League was not as powerful or united as it could have been.

Yet Roosevelt, by the time he got into the office of the presidency by winning the 1932 presidential election, would go about attempting to reaffirm more open international diplomacy and economic vision concepts through his first two terms in office anyway, even as the League floundered and war in Europe became inevitable, and eventually world consuming. For the most part, he was able to act in this vein positively, although his policies towards Japan could be pointed at as an exception to this general vision; the souring of relations with the Japanese, and the subsequent economic measures utilized against them did, indeed, help to facilitate an atmosphere in which Japan might attack the United States in retaliation for these economic rebukes, but came after levels of overt Japanese military extension and aggression that, in the modern world, were it done by a nation like Iran or North Korea, would be seen as massive, major international incidences with tremendous, globally catastrophic consequences.

But the attempt by FDR in 1935, as one of his predecessors, Calvin Coolidge, had tried for in 1926, to enter the United States into the World Court, of which both men believed could provide international stability and diplomatic recourse for all nations, including America, was rebuffed by a selfish, shortsighted and reactionary Senate, much as it had been during the Coolidge administration as well. In the case of FDR, this was the attempt of someone who saw that large scale cooperation, trust and arbitration was going to be key to solving international misgivings and incidents in the coming years and decades. Had the United States begun participating in either 1926 or 1935, this innovation, if collectively managed and actively tended to, might have given some recourse to the nations of the world in the years to come outside of outright war.

For his third presidential term, Franklin Delano Roosevelt chose the former Secretary of Agriculture, and the future Secretary of the Treasury, Henry A Wallace, as his vice presidential candidate. Wallace was very likely the most liberal, or even leftist, of all of this nation’s Vice presidents, and he was acutely aware of the need for the creation of an international sense of mutual trust, accountability,and participation. On the 8th of May, 1942, while he was in the middle of his term as vice president to the nation, Wallace gave a speech that would come to be most famous for the phrase, “the century of the common man,” but which would, to be sure, outline his vision for an American led future that had this nation more as a benevolent partner than as the hegemonic force.

No nation will have the God-given right to exploit other nations. Older nations will have the privilege to help younger nations get started on the path to industrialization, but there must be neither military nor economic imperialism.

Wallace not only wished for America to transcend military and economic imperialism, but wished for the United States to use its vast economic power in quite the opposite way; to draw in those nations America was in disagreement or at loggerheads with, rather than to bring them into some type of economic or diplomatic submission or face international purgatory.

Wallace, however, would not get the opportunity to be president of the United States. Led by conservative Democrats like South Carolina’s own Jimmy Byrnes, plans were made to subvert the people’s truest choice, Wallace, as the vice presidential candidate in 1944, and instead replace him with someone perceived to be more malleable: Missouri Senator, and Boss Tom Pendergast favorite, Harry S Truman.

Wallace would be given the Treasury Secretary position for the fourth Roosevelt term, and that would be the closest he would ever come to the Presidency again; when the president was sitting for a portrait just months after winning his unprecedented fourth presidential election, a hemorrhagic stroke would take him, and in turn, leave Truman as the new president, and leave Wallace shortly out of a position in the Federal government. During the Truman and Eisenhower presidencies, Wallace’s vision for the world was, as it had been in the earlier part of the century with the incapacitation of Woodrow Wilson and his Treaty of Versaille, largely lost, and this time, it was replaced by that economic domination and imperialism that Wallace had warned about just years before.

Henry A Wallace responded to these developments in the post-Rooseveltian era with, as well as in, many of his correspondences and speeches, both as a public and private citizen; these beliefs regarding international mutuality and cooperation were as powerful then as they continue to be today. Two further passages, in fact, are most fascinating and enlightening in my estimation regarding this. One comes from a letter that Henry A Wallace wrote to President Truman on 23 July, 1946, which highlights his vision of the American international responsibility.

The real test lies in the achievement of international unity. It will be fruitless to continue to seek solutions for the many specific problems that face us in the making of the peace and in the establishment of an enduring international order without first achieving an atmosphere of mutual trust and confidence….

The postwar order

And while such an international order as the United Nations was, indeed, developed as the Second World War was coming to an end, its most economically powerful members have chosen to use their imperial powers, not to work through issues with active, collective diplomatic proceedings, but to use material and economic means as a cudgel with which to force the submission of those who sit in opposition to the international majority in some manner. Contrary to the vision that Henry A Wallace had for this nation, the United States would not be shy when using this cudgel in the coming years and decades, to be sure. And it is a speech of which he gave less than a year later that further illustrates a point that we as Americans today should consider when appraising our international neighbors and their own circumstances. In this speech castigating then-President Harry Truman’s policies aimed at containing Russia through financial and economic pressures, Wallace had, on 13, March, 1947, both a rebuttal and rebuke for the foreign policy views of the current president.

The world is hungry and insecure, and the peoples of all lands demand change. President Truman cannot prevent change in the world any more than he can prevent the tide from coming in or the sun from setting. But once America stands for opposition to change, we are lost. America will become the most-hated nation in the world. Russia may be poor and unprepared for war, but she knows very well how to reply to Truman’s declaration of economic and financial pressure. All over the world Russia and her ally, poverty, will increase the pressure against us. Who among us is ready to predict that in this struggle, American dollars will outlast the grievances that lead to communism?

Sadly, Wallace’s warnings were largley ignored during the Cold War, as economic coercion became a mainstay of US diplomacy. And in today’s age, we might simply substitute neo-fascism, theocratic fascism, or even still the heavily bastardized “communism” of China, for the communism that Henry A Wallace referenced in his speech. Yet still the timbre of the language and ideas of Mr. Wallace remain remarkably relevant and poignant over 70 years after they were first uttered. When we as a nation look to suffocate or suppress humanity, instead of working towards a common, multilateral solution to assist them, and bring them into a more stable and fruitful position within the international community, we only give strength to the most reactionary and grotesque forces of, not only those particular nations, but of the greater world as well.

How, therefore, can Joe Biden and the US change its previous patterns, beliefs and actions, and instead behave differently, with greater empathy, mutuality, as well as diplomatic and practical efficiency, upon the international stage?

Recent history shows that our current path was not inevitable and need not be permanent. We would not even have to go back to the days of Roosevelt and Wallace, but only to those of Obama and Biden, whose effort to work with Iran made it possible to craft the JCPOA and lift a number of sanctions. The ambition and spirit of innovation in this effort should be remembered and applied to foreign policy moving forward.

None of this is not some great secret, and if anything, it is a more historically common phenomenon than true sanctions have been for much of the last 2000 years or so; actual discussions and negotiations need to be ongoing with and between the United States and nations that we do not get along with on a regular and routine basis. Talks such as those that were secretly taking place between the administration of the 44th president and then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, need to, in fact, become the standard and norm in looking to break down the international barriers that separate the United States from certain other nations of this world, and not the exception.

Now, of course there are circumstances where this is not and will not be reasonable, such as with North Korea, who do not actually wish for any good faith negotiations with the United States at this point, no matter who the president is. Even there, however, sanctions have not worked, other than to ensure that the population, smothered as they are by the ruling regime, have even less potential to acquire the very necessary resources to live without rampant illness, malnourishment and suffering. Meanwhile, North Korea was, under the reign of Kim Jong Il, the single largest importer of Hennesy in the entire world, while his son and the nation’s current leader, Kim Jong Un, has at least two Maybachs, so there you are, eh?

And so while the North Korean question is one of the most difficult of conundrums to work through, and deserves the sole focus of another essay, for nine out of ten international relationships, good faith negotiations in the hope that agreements or some type of plan might be worked out so as to afford all parties better relations within the larger international community, and particularly the United States, can be productive. The greater world is under fewer delusions regarding the morality and efficacy of sanctions, and so I believe that this more direct, straightforward means of working through any real international issue would be embraced by most nations, regardless of their state and status in the world.

An opportunity

Ironically, the nations that would likely be most averse to this suggestion are likely to be those polities like Russia, China, and the United States of America. All three of these nations have a relatively recent history of disregarding international advice, opinions and collective, cooperative diplomatic bodies as it suits them regarding both domestic and international activities, and would therefore likely be the most obstinate to any other nation or groups of nations scolding them, or offering them advice regarding their behavior.

But for Joe Biden, this type of decision could leave him with a genuinely positive foreign policy legacy. Similar to the hurdles that exist when attempting to get a dilapidated nation fixed up, there will be difficulties in first convincing people of the benefits of being the internationally “larger person,” reaching out to nations who outwardly show disdain for America with an open hand instead of punishing them with the brutish power and force of a closed, and oftentimes cocked, fist. There will, undoubtedly, be protests, however minor, regarding any deal that might be twisted and manipulated by ring wing commentators and politicians to resemble what they like to refer to as bad deal-making, and yet this too must be disregarded by the 46th president, no matter his eye on the polls and polling numbers.

While the Iran Deal was criticized by politicians and pundits alike, the American public now favors a return to some type of deal akin to it by a healthy majority. The American public is beginning to understand better that only through cooperation, even with those whom we do not particularly love or like, can we make a positive impact and help to build a peaceful or sustainable world; sanctions, on the other hand, have gotten us to the point that we are currently at, and that is the direction that we are looking towards traveling further in should we fail to remedy this delusional diplomatic recourse.

Belarus is not going to behave any differently because the EU and the United States placed sanctions upon them, because they have the likes of Russia to help them, and while Russia is also, of course, sanctioned, they continue to suffer through them just as Iran has. Russian sanctions, the most devastating coming from their first incursions into the Crimean region of Ukraine during the Obama administration, might be justifiable in the minds of many, and indeed, invading another country is what sanctions are outwardly meant to discourage. Yet with the recent news that Russia is planning on invading this disputed region of Ukraine anyway, might some other concerted, united and socially less harmful means of deterring Russia have been utilized all along?

I believe so, and I believe that that recourse might have been achieved by a united diplomatic front of nations that focused on dealing with Russia, at a level similar to these Vienna discussions vis-a-vis Iran, whilst intimately involving Ukraine and the other polities of the region, instead of sanctioning Russia into retreat and disconnection with the separatists in Crimea. These sanctions, while harsh and further intensified in the following years, are reported as having worked and hurt oligarchs, the Russian economy and the like, do not damage the leaders of Russia’s economic and political world enough to, somehow, shift their world views away from their current positions.

The current Crimean issue is a great example of this, in that years of sanctions have not forced Putin’s Russia to come groveling back to a negotiating table, and instead, the nation has recently amassed troops all along the Crimean border. Vladimir Putin would not let the sanctions of Obama, Trump or Biden appear to define his actions, or his nation’s plight, similar to Iran, and so the imagined, romanticized scenario where sanctions work to bring nations and their peoples back to the proverbial bargaining table, continues to be proven as fictitious as ever. It never does this, and it seems unlikely that it ever will either.

Yet in any event, while Russia and Iran both suffer, they each understand, and have long understood, that the best way to beat them is to simply carry on as though they do not exist, while simultaneously complaining about the burden that the population bears because of them. Belarus, or Ethiopia for that matter, will have to be addressed in individual, multilateral discussions that, like the Iranian discussions, work with other internationally and regionally powerful nations, such as Russia and China, to create an accord that can allow for the economic and social conditions that are vital for any and all people to flourish, wherever they may be on this planet.

Meanwhile, the easiest thing that President Joe Biden might do regarding his foreign policy outlook, which can be accomplished as soon as he likes without any need for any congressional hooplah, would be to lift the sanctions that the Trump administration placed upon both Iran and Cuba during his four years in office, and that the 46th president added onto earlier this year. Should Biden wish to hold firm regarding the sanctions that he himself added to Cuba upon taking office, he could likely use those specific sanctions, and relief from them and the famous US-Cuban travel restrictions, to entice a Vienna style conference between the United States, its allies and Cuba in Brussels or The Hague.

This all would be a clear indication that this American president, differing from many of his predecessors, was able to see the vapid, worn logic that follows sanctions and their champions from the historical perspective down the years. It would take a great deal of bravery to stand defiantly in the face of what has become common diplomatic wisdom and recourse for powerful nations when dealing with their enemies and the less powerful nations of the earth, but just as predatory behavior across other walks of life have been slowly and steadily judged more barbaric and less acceptable as society has continued to evolve, so must this practice. Like the siege and barricade before it, the sanction will have, by the time it finally dies, far outlived whatever usefulness it may have at one time held, whether practically and functionally, or in the theoretical sense. We witness it now, at this date, only as the ghoulish phantom we see before us that, sooner or later, stalks each and every polity of the world, all the way up and down the proverbial international food chain.

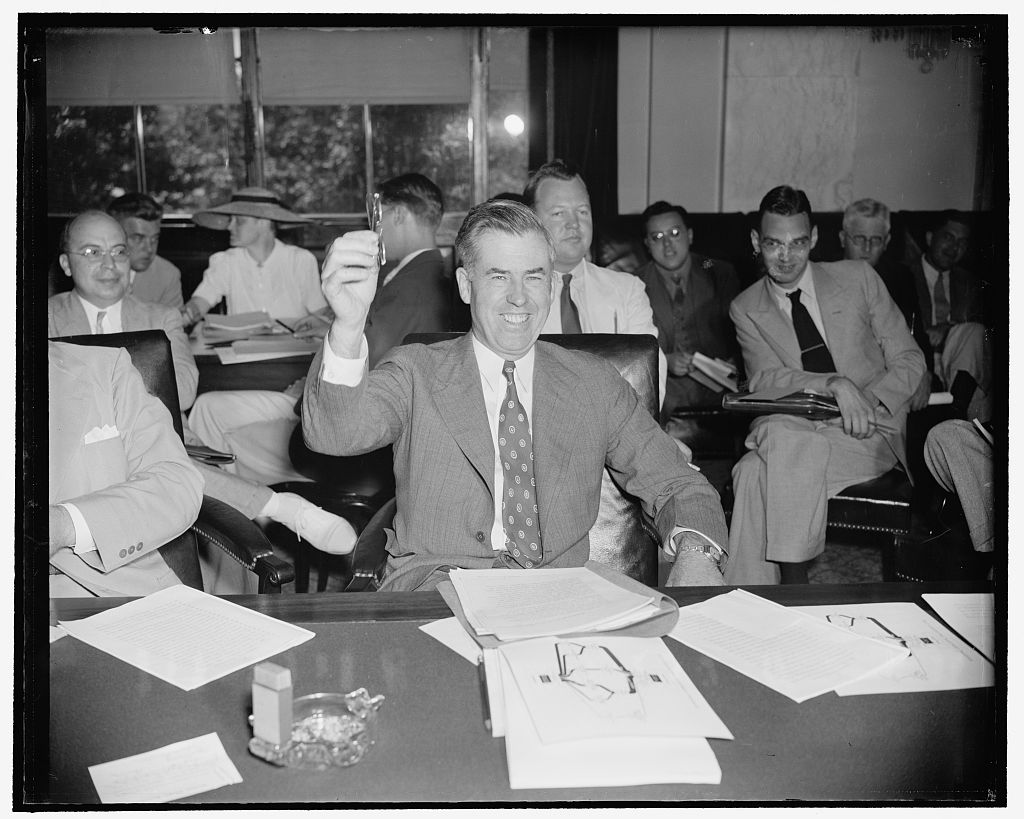

Featured Image is Henry A. Wallace