Reclaiming Nationalism as an Ally of Liberalism

In 2019, the liberal European parliamentary group Renew Europe won its best election result since 2004. Reflecting on that result, the president of Renew Europe, Dacian Ciolos, wrote, “Europeans have given us a strong mandate to change Europe for the better…[Renew Europe] will stand up for the people who suffer from the illiberal and nationalistic tendencies that we see returning in too many countries.” The implication was clear. Nationalism is clearly linked with illiberalism, and both are obstacles in the process of “changing Europe for the better.”

Most liberals would agree with Ciolos’ sentiments. In turn, nationalists sneer at liberals as “citizens of nowhere,” as former Prime Minister May put it.

With each year, each election, and each new populist firebrand, the antagonism between liberals and nationalists grows. To modern liberals, it is tempting to view history through a type of neo-whiggish framework where nationalism becomes just another opponent of liberalism, soon to be defeated much as the Bolsheviks, fascists, and Bonapartists were.

It was not always this way. Even in the recent past, prominent liberals were nationalists, and prominent anti-nationalists were more likely than not to oppose liberalism. The liberals whose resistance brought down Soviet-style communism in Eastern Europe were firmly nationalist—whether they supported independence from the Soviet Union as in the Baltics, national autonomy as in Poland, national reunification as in East Germany, or return to their national homeland as with the Soviet Jews. The great liberal theorists of the past were avowed nationalists—John Stuart Mill voraciously defended Britain’s foreign interests to establish colonies (though we should note the racist elements of Mill’s apologia here), while the Marquis de Lafayette stubbornly refused to join the United States government to work for liberty only in his homeland. Both Mill and Lafayette, while prideful of their nations and supporting its interests above others, promoted peace between nations and rejected isolationism. Major Western nationalist politicians such as Begin, De Gaulle, and Adenauer embraced free market economics, social liberalization, and a regulatory state.

The end of the Cold War coalition

If we want to end the alienating modern conflict between liberalism and nationalism, we have to understand how it began. Liberalism has always, in its theoretical forms, expressed a preference for internationalism and multilateralism. The Oxford Manifesto of 1947, which defined post-war liberalism and founded the Liberal International, an association of worldwide liberal parties, expressed a desire that “all nations [show] loyal adherence to a world organisation of all nations, great and small, under the same law and equity, and with power to enforce strict observance of all international obligations freely entered into.” Liberalism is so amenable to internationalism because, fundamentally, all unjustified barriers to commerce and individual liberty, whether between nations and citizens or between two nations, are repulsive to it. The Corn Laws that imposed internal tariffs on British corn imports and spawned The Economist are as illiberal as the trade barriers between Britain and France that The Economist opposes today.

During the Cold War, however, liberals and nationalists made common cause against the Soviet Union and its allies, which required compromises from both sides. Many nationalists came to support regional defensive pacts and limited economic integration to ward off communism, while many liberals supported a more hawkish foreign policy over a universalist one to pressure the Soviet Union and its allies. This relationship was not unstrained. The issue of détente in the seventies was opposed by nationalists, and the aggressive military interventions prosecuted from the Falklands to Grenada in the eighties were opposed by liberals. But the bond held through the Cold War.

After the demise of Soviet-style communism as a theoretical and geopolitical threat to liberal democracies in the early nineties, the cracks in the liberal-nationalist alliance quickly emerged. Francis Fukuyama famously proclaimed the “End of History” in a 1989 essay and 1992 book, declaring, “What we may be witnessing is…the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” While he is often misinterpreted as arguing that nothing would ever challenge liberalism again, he did argue that liberal internationalism had triumphed on its own, and that nationalism, too, was among the defeated ideologies.

Liberals, following his vision, claimed a mandate to effect worldwide political change, beginning in Europe and quickly expanding outwards. The end of the Cold War brought about the European Union and with it the Euro, the supranational European Parliament, and the Schengen Zone. In North America it brought with it NAFTA, the finally realized dream of a continental free trade area. In Asia it brought about the liberal economic reforms of Vietnam and China, and the ascension of those nations to the World Trade Organization. In Latin America it brought about the end of the illiberal juntas and the formation of Mercosur and the Andean Community. Liberal reforms, especially liberal reforms to trade sovereignty and the economy, swept the world. Worldwide, liberals ended their alliance with nationalists to finally pursue truly anti-nationalist policies.

As Fukuyama was writing his End of History, the Israeli liberal politician Yael Tamir wrote a prophetic rejoinder, Liberal Nationalism. In her introduction, she argued, in 1992, that, “the twenty-first century is unlikely to see nationalism fade away. Liberals… must come to terms with the need to ‘share this glory’ with nationalism.” While both Tamir and Fukuyama hoped for a similar future—regional cooperation, the spread of democracy, universal social liberalism—Tamir, perhaps because of her proximity to the nationalist dilemma of Israel and Palestine, did not believe nationalism was vanquished. If anything, she saw the end of communism empowering nationalism.

History since the End of History has proven her right. Peru was the harbinger of revitalized nationalism. Their third post-junta elections, in 1990, were contested by the neoliberal novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, the socialist former Prime Minister Luis Alva Castro, and the nationalist professor Alberto Fujimori. When Alva Castro was narrowly defeated in the first round, he endorsed the vaguely moderate Fujimori over the favorite, Vargas Llosa. Fujimori, enjoying support from both the traditionally left-wing rural natives and lower-income urban workers, won the election in a landslide. Fujimori would govern for the next ten years as an increasingly autocratic nationalist, and today resides in a Peruvian prison for crimes against humanity.

Even as liberalism expanded through the halcyon nineties, nationalism enjoyed a frequently misinterpreted revival as well. The case of the former Yugoslav states is widely known, as are the low-level wars of the Caucuses. But nationalism did not just expand through the post-Soviet world. It re-emerged in the Palestinian territories, where, after decades of occupation, Palestinians began the infamous and brutal First Intifada. It re-emerged in Rwanda, where a fragile multi-party democracy collapsed and the horrific Rwandan genocide began under Hutu nationalists. It re-emerged in South Africa, where apartheid was defeated by international pressure and sanctions, but also by strengthened Pan-African nationalism in the ANC and Zulu nationalism in the IFP. South African liberals, while anti-apartheid, played little role in dismantling the regime and never enjoyed political success pre- or post-apartheid. It re-emerged in Japan, where the first government not dominated by the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party since 1955 collapsed. It re-emerged in Quebec, where, after over two hundred years of stillness, Quebecois nationalists came within a half point of independence. While each nation saw the new rise of nationalism differently, and in each case it emerged under unique circumstances, the trend was clear. Once communism ceased to be a threat, nationalism roared back, whether in a liberal democracy, a post-communist state, or a non-aligned dictatorship.

The pursuit of internationalist liberal policy goals alienated their one-time allies among the nationalists, as well as decisively cutting off the liberal nationalists Tamir had described. President Clinton, for example, supported a dramatic anti-nationalist package in NAFTA despite widespread opposition within his own party and nation under the benign theory that since the liberals had won the world, opposition to NAFTA was a paper tiger. His subsequent loss of Congress in 1994, and the use of opposition to NAFTA as a rallying point from populists left and right even today shows the enduring strength of nationalists.

Nationalism’s persistence

The past thirty years, and especially the past ten, have shown us conclusively that nationalism is not going anywhere. What was murky even in the nineties seems clear now. Anti-European Union nationalists successfully withdrew Britain from the EU and, though their support has waned recently, still threaten the total dissolution of the EU. United States nationalists elected the first true anti-trade president since the days of the Hawley-Smoot Tariff in Donald Trump. Argentine nationalists threaten to dissolve Mercosur. Liberals feel attacked by nationalists, who in turn feel that liberals seek to dissolve their very identity.

Nationalism will not fade away as have the other ideologies vanquished by liberalism. As Edmund Burke wrote, “[the nation] becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are yet to be born.” A partnership based on the purely material concerns of the present, as in, for example, a communist state, is far weaker than one based around a commitment to one’s ancestors and to one’s children. Unlike the historical “opponents” of liberalism such as socialism or communism, nationalism ties itself inextricably to the past, and nationalists, unlike socialists or communists who may be motivated by their present suffering, and may be motivated by a feeling of inevitability and destiny from their national past. This process will not end when nations lose their connection to the past, or when new nations or peoples develop. Anthony Smith described the process by which, “[nations] which could not fall back upon a… long and rich cultural heritage sought to imitate those which could do so, by, if necessary, ‘inventing’ or rather ‘rediscovering’ and ‘annexing’ histories and cultures for their people…” Hence no matter how the future progresses and what new peoples emerge, a nationalist sentiment will always persist among them.

The issue for a modern liberal, given that liberals have cooperated with nationalists in the past, and given that nationalism is not some final obstacle to overcome but a common expression of enduring features of mankind, is how to use nationalism to achieve liberal ends without compromising liberal ideals. There are three general approaches: expanding a national identity, redefining a national identity through civic nationalism, and minimizing national sentiment.

Expanding a national identity refers to recasting existing national sentiment to a broader scale. Think, for example, of an ardent English nationalist who becomes a British nationalist. While still remaining a nationalist, our hypothetical lion is now in favor of free movement, free trade, and free flow of capital between England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, in favor of the rights of Welsh, Scottish, and Irish minorities, and in favor of a common military and defense of the islands. While remaining a nationalist, the nationalist achieves practical liberal goals.

A similar process occurred in the United States. Though we often forget it, after the American Revolution, and at least until the Civil War, citizens of the United States were more likely to identify with their state than with the Union. Describing the political order in the antebellum United States, de Tocqueville wrote that “the Federal Government is… the exception; the Government of the States is the rule.” They remained nationalists but they advocated for a stronger central government, greater economic activity between the states, and a pan-state identity. A similar process is occurring today in Europe, where nationalists seeking independence use the concept of the “Europe of Nations” to envision a federal Europe where Scotland, Catalonia, Brittany, and the rest are free of their nation state though subject to a broader European government.

The best example of this process is Botswana. Upon independence in 1966, Botswana was one of the poorest nations in the world. Today it is a widely regarded upper-middle income nation with a strong democratic tradition and good relations with the world. Undoubtedly this is a result of liberal policies being implemented by the Botswana Democratic Party from independence onwards, but an underappreciated facet of Botswana’s success is expansion of nationalist sentiment. Prior to independence, Botswana’s politics were dominated by relationships between various Tswana tribal groups, as in many African nations. But the early government of Seretse Khama, and his successor governments, worked very hard to create a pan-Botswanan nationalism, even going so far as to mandate forced movements of people to disrupt tribal lines. His success led to Botswanans identifying primarily with Botswana, not their Tswana tribe or ethnic group, which in turn fostered the strong state we see today. The transformation of nationalism from a tribal or ethnic nationalism to a central nationalism achieved liberal policy without alienating nationalists.

The second method of incorporating nationalism into a liberal agenda is through civic nationalism. Civic nationalism incorporates elements of shared culture and identity while retaining liberal values such as inclusivity, diversity of expression, and respect for different cultures. The best example for this practice is undoubtedly Canada, which, while taking in large numbers of immigrants, refugees, and migrants, has retained and even strengthened its cultural identity. Canada today does not suffer from nationalist extremists, and both major parties have to some extent co-opted nationalist imagery while supporting liberal values. According to Tamir, liberalism is entirely sympathetic to this concept: “In order to sustain its character as a law-abiding and caring community, the liberal state must view itself as a continuous community rather than a causal association of parties.” How does one distinguish between a “continuous community” and a “causal association of parties?” Tamir argues a successful liberal state will incorporate both “general civic competence” and “shared culture and identity.” A civic nationalist liberal state melds the two while retaining liberal values. Civic competence is always a liberal pursuit, of course, while a shared culture and identity can be created through values of freedom, tolerance, and reverence of social mobility instead of an illiberal pursuit of forced assimilation and nationalization to encourage conformity.

Finally, hypernationalist sentiments can be diffused among subnational entities. While there are many advantages to federalism, especially across large nations, which we need not explore in great detail, for our purposes one of the keenest may be that it weakens nationalist sentiment. Aggressive nationalism is often aggravated by particular regional issues, and directing that anger and energy towards a regional government allows a liberal state to insulate itself from populist fury. Germany has collectively rejected nationalism for many reasons, but it has also resisted nationalism even today by creating a system that marginalizes nationalist sentiment located in specific regions. The German state today is strongly federal, and nationalist parties and movements, such as the AfD (Alternative for Germany) are kept “quarantined” in their bases of support, chiefly the former East Germany and Baden-Württemberg. Even within a proportional, democratic electoral system, the AfD is penalized for not being a truly national movement. The AfD also is forced to contend with state governments, where it is excluded from government and unable to demonstrate competence on a local level, which is how other successful German “third parties,” such as the liberal FDP (Free Democratic Party) and the Greens, have risen to national prominence. A system of regional, localist government diffuses nationalist fury and isolates extreme nationalists from overcoming a nation in one fell swoop.

Nationalism is a permanent facet of human existence. Liberals do best to not see it as an opponent, but rather a potential ally, as they did during the Cold War. The rejection of liberal nationalism and the embrace of a confrontational mindset after the end of the Cold War mistakenly alienated those partners, and led to the nationalist reaction western nations endure today. The liberal policy goals we seek are not, for the most part, anti-nationalist, and there is little conflict between nationalist and liberals on most issues. Collaboration is key, and in the areas where it is not, there are less aggressive ways of overcoming nationalist opposition, whether it be reframing nationalism on a larger scale, fostering a more moderate civil nationalism, or isolating nationalists regionally.

To adapt, liberals ought to implement these successful methods. They are proven to work, it simply requires us to adapt them to our local circumstances. Defeating hyper-nationalism by co-opting its best points and cultivating a civic concept of a nation is universal. Redefining, say, nationalism within the United States to refer to a pan-American nationalism, or turning the specter of Brazilian nationalism into pan-Latin nationalism is, while difficult, a winning argument in the long term. Federalism, a long standing liberal objective, is eminently reasonable. Any liberal that bemoans the rise of euroscepticism or protectionism must offer not just an alternative to it, but an “out”—a means to bring nationalists into the cause and build a broader coalition without forcing them to admit total defeat.

Liberals have long prided themselves for their adaptability, and their efficiency in stealing the best ideas of other ideologies. In this case, liberals will either adapt to once more incorporate nationalism, or they, too, shall come to pass.

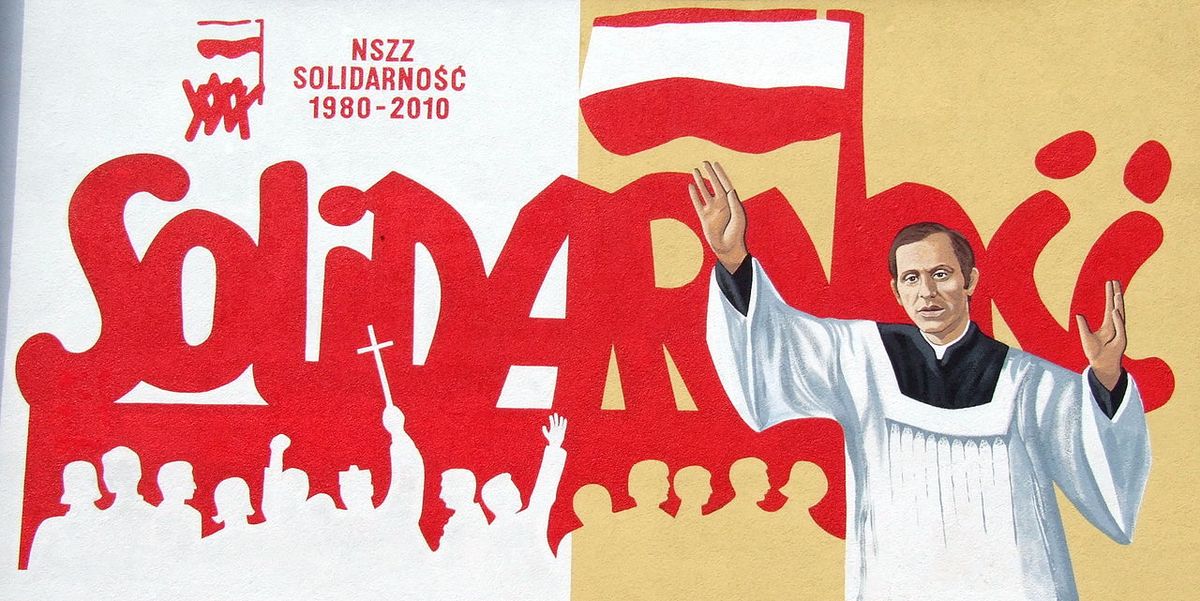

Featured image is mural of Solidarity