Trump Must Lose the Second Bank War

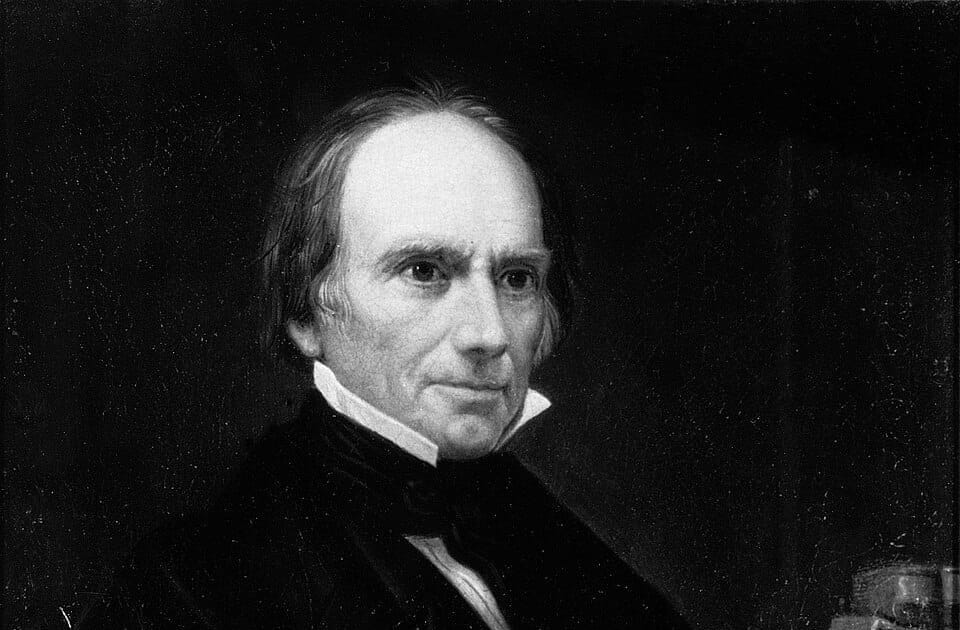

Henry Clay understood what was wrong with the unitary executive theory back in the 1830s.

“Eventually, executive power will become completely uncontainable, and our beloved constitutional Republic will be no more,” Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson predicted in her recent dissent from the ruling in Trump v. CASA, Inc. Current events have proven her a Cassandra.

To date, the principal project of the second Trump administration has been dragging the United States closer and closer to the tipping point Justice Jackson described, a fact widely ignored by Democratic elites and the political press. The ongoing attempt to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook renders this unmistakable, as does the drafting of a letter to fire Fed chair Jerome Powell. Usually justified by reference to the Vesting Clause, the White House’s basic argument is that the president enjoys essentially unlimited control over the executive branch so any Congressional limits on the power of dismissal are unconstitutional. (Fellow Liberal Currents contributor Pat Sobkowski has written a good summary of this doctrine, known as “unitary executive theory,” which you can find here).

Inveterate contrarian Sohrab Ahmari, Unherd’s U.S. editor and cofounder of Compact magazine, has argued that Trump’s clash with the Federal Reserve isn’t just one more manifestation of an imperial presidency. Instead, his column maintains attacking Fed independence is a warranted reassertion of democratic control over the economy. Comparing Trump to Andrew Jackson, Ahmari lexically smirks as he points out that the party Jackson founded is now rallying to the defense of an independent central bank.

“At issue, now as then, is whether the shape and management of US currency and the money supply should be subject to democratic contestation — or left to the supposedly ‘neutral’ determination of expert bankers,” he claims. I’ve already made the case for Andrew Jackson’s presidency as the best historical parallel for Trump so I cannot say Ahmari erred in his choice of analog, and would not do so even if I wasn’t already on the record concurring with him there. However, Ahmari draws precisely the wrong conclusions in his comparison of the two presidents. Despite President Jackson’s pretensions, the Bank War he began was not a mass movement against unelected, usurious elites. It was a president grabbing at power denied to him by the people’s duly elected representatives in Congress, as is Trump’s recent feud with the Fed.

Historian Daniel Walker Howe writes in his Pulitzer winning tome about America in the early 1800s, What Hath God Wrought, that President Andrew Jackson “believed in the sovereignty of the American people and in himself as the embodiment of that sovereignty [emphasis added]” (367). In an overwrought but not inaccurate note also with modern resonance, the editor of an 1857 collection of Henry Clay’s speeches similarly lamented that “the Constitution and laws were little regarded, if they stood in the way of the will of General Jackson.”

Despite popular critiques of Jackson in the 1830s, “the Bank War was not a class war of labor against capital or the propertyless against the propertied,” Howe writes. “Jackson gave voice to the feelings of farmers and planters who resented their creditors as much as they needed their financial services. But he was also supported by elements of the business community who had reasons of their own to join in an attack on the [Bank of the United States]” (382).

He continues by explaining that “Jackson’s victory over Biddle’s Bank did nothing to reform the abuses from which the average person suffered. The elimination of the national bank removed restraints from regional and local banks, enabling them to behave more irresponsibly than ever” (383). (To Ahmari’s credit, he does note this in his piece.)

Jackson’s battle against the Bank of the United States, fueled in large part by his own grievances (375-376), only escalated after his re-election. He appointed William J. Duane, recognized as a critic of the Bank, to be secretary of the Treasury in order to facilitate the removal of the United States’ deposits from Biddle’s institution. When Duane refused to do so, partly on the grounds that Congress had tasked the Treasury secretary and not the president with determining when to remove the deposits, Jackson fired the man he’d just appointed. Duane’s replacement, the interim secretary Roger Taney, began depositing federal funds into state banks. This was so shocking that secretary of state Louis McClane and secretary of war Lewis Cass both tendered resignations, which they were then convinced not to carry out (387-388).

By firing Duane and effectively removing federal deposits from the Bank of the United States, Jackson plunged himself into a heated, months-long battle with Congress not over the rechartering of the Bank but over the very nature of the presidency. The true scope and stakes of the fight is revealed by the response of the country’s great statesmen, especially Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, to Jackson’s overreach.

In a spirited speech before the Senate on May 7, 1834, Webster eviscerated Jackson’s proffered defense of his actions. The president had sent a message to the Senate in April after that body formally censured Jackson’s actions, claiming for his office the right and duty to defend the Constitution as well as the mantle of the “direct representative of the American people.” Webster retorted:

The President is President. His office and his name of office are known, and both are fixed and described by law. Being commander of the army and navy, holding the power of nominating to office and removing from office, and being, by these powers, the fountain of all patronage and all favor, what does he not become if he be allowed to superadd to all this, the character of single representative of the American people? Sir, he becomes, what America has not been accustomed to see, what this constitution has never created, and what I cannot contemplate, but with profound alarm.

Webster and those drawn with him into the new Whig party began the Bank War conceding the ability of the president to remove officers in the executive branch, belief in which had become widespread following the Decision of 1789: a series of debates in the First Congress over when and how executive officers could be removed that appeared conclusive after executive removal had become common practice. By the time the Bank War began drawing to an end, they—like the Founders and members of the first Congress—were openly questioning whether the president had any inherent power to remove officers.

Legal scholars Lawrence Lessig and Cass Sunstein posited in a 1994 article making the positive case for unitary executive theory that Clay’s description of the firing of William Duane in 1837 was “perhaps our last glimpse of the framers’ conception of the President’s power” (81). That “last glimpse” served as part of the Kentucky senator’s protest against expunging the Senate’s censure of Jackson from the body’s journal, a censure Clay had supported and shepherded through to passage.

“Our British ancestors understood perfectly well the immense importance of the money power in a representative government,” Clay averred in the speech. “It is the great lever by which the crown is touched, and made to conform its administration to the interests of the kingdom, and the will of the people. Deprive Parliament of the power of freely granting or withholding supplies, and surrender to the king the purse of the nation, he instantly becomes an absolute monarch.”

By this time already twice a presidential candidate and first elected to Congress over thirty years previously, Clay outlined how public funds had long been purposefully kept outside of the president’s direct control. The senator tore apart contemporary arguments that the Constitution grants the president an unqualified power of dismissal in defense of the Senate’s right to censure the president outside of impeachment proceedings.

Now Ahmari, with a glint in his eye, asks his readers “if the government endows an institution like the Fed with its authority, why should its officeholders be beyond the reach of the democratically elected president?”

Clay, speaking in December of 1833, rebutted Ahmari’s pretense simply and effectively:

The real inquiry is, shall all the barriers which have been created by the caution and wisdom of our ancestors, for the preservation of civil liberty, be prostrated and trodden under foot, and the sword and the purse be at once united in the hands of one man?

He added, later in the same speech:

The truth is, that the re-election of the President no more proves that the people had sanctioned all the opinions previously expressed by him than, if he had the king’s evil or a carbuncle, it would demonstrate that they intended to sanction his physical infirmity.

Jackson, as Trump does now, falsely believed his re-election was a mandate for pursuing all of his policy preoccupations, legal and Constitutional limits be damned. I’ve already conceded Ahmari’s argument that Trump has been behaving like his idol Jackson is essentially correct. The issue, however, is not whether a “democratically elected president” has some arbitrary right to dismiss their secretary of the Treasury, or a member of the Fed’s board of governors.

The crisis that is facing us today is whether the Congress of this country still has the power to place fetters on a would-be king. Presently, with every day we grow closer to that aforementioned point where “executive power will become completely uncontainable.” And as Webster attested almost two centuries ago, “the contest, for ages, has been to rescue liberty from the grasp of executive power.”

“Whoever has engaged in [liberty’s] sacred cause, from the days of the downfall of those great aristocracies, which had stood between the King and the people, to the time of our own independence, has struggled for the accomplishment of that single object,” Webster declared. “On the long list of the champions of human freedom there is not one name dimmed by the reproach of advocating the extension of executive authority; on the contrary, the uniform and steady purpose of all such champions has been to limit and restrain it.”

Bibliography

Clay, Henry. Speech of the Hon. Henry Clay, on the Subject of the Removal of the Deposites: Delivered in the Senate of the United States, December 26, 30, 1833. D. Green, 1833. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/3712/.

Clay, Henry. The Works of Henry Clay: Comprising His Life, Correspondence and Speeches, edited by Calvin Colton. Vol. 8. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Lessig, Lawrence and Cass Sunstein. “The President and the Administration.” Columbia Law Review 94, no. 1 (January 1994): 1-123. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1123119/.

Webster, Daniel. Mr. Webster’s speech on the President’s protest: delivered in the Senate of the United States, May 7. Gales and Seaton, 1834. https://www.loc.gov/item/10008664/.

Featured image is Henry Clay, by Oliver Fraser