Walking Backwards to Walk Forwards: Günter Grass’s Crabwalk and Reliving the 20th Century

In his magisterial history of postwar European history, aptly titled Postwar, Tony Judt writes, “Europe’s postwar history is a story shadowed by silences; by absence. The continent of Europe was once an intricate, interwoven tapestry of overlapping languages, religions, communities, and nations […] Between 1914 and 1945, that Europe was smashed into the dust.” If the old Europe was smashed to dust in those years, where does that leave America? In the 1950s and 60s, America posited itself as the model of economic and civil life in the nuclear age. Key to this self-image was America’s ostensible lack of extremist ideology in its leftist and rightist forms. After the election of Donald Trump, the idea of a “post-ideological” America appears a fantasy, if not downright delusional. The resurgence of ideological extremism playing out in the streets of America seems surprising, but was prophesied in the German writer Günter Grass’s 2002 novel, Crabwalk (Im Krebsgang). What Grass finds in this work is that the tendency towards ideological violence is cyclical and is carried forth into existence by those bearing deep scarring from those who witnessed some of humanity’s worst crimes in the twentieth century.

Crabwalk tells the story of three generations of Pokriefkes, a petit bourgeoisie family from the former Free City of Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland). Tulla, the oldest, experiences the sinking of the Nazi Kraft durch Freude ship, the Willhelm Gustloff firsthand during her escape from Danzig as it is assailed by the Soviet Union. The Russians attacked the doomed vessel in question as it was carrying refugees and wounded away from the city (the ship also housed materiel as well). On the sinking ship, Tulla gives birth to her son, Paul, who becomes a journalist in the newly minted German Federal Republic. Tulla, by contrast stays in East Germany which becomes the Soviet-controlled German Democratic Republic (GDR). Paul fathers Conrad “Konny” Pokriefke, who becomes obsessed with the maritime disaster, and the ship’s namesake, the leader of the Swiss Nazi Party who was assassinated by a Jewish leftist in 1936.

Crabwalk begins with the words “Why only now?” (Grass, p. 1). This question carries with it a sense of historical baggage – that the feelings of loss and trauma associated not only with the nautical disaster, but with the loss of Danzig as a homeland, are processed only after disaster strikes. This “late processing” does have an ideological component. Tulla processes this loss through the lens of East German communism, as Nazi victimization of the future denizens of the “Workers’ and Peasants’ State.” Paul, who narrates the novel, recollects that Tulla calls herself “Stalin’s last faithful follower” while praising the Nazi Kraft durch Freude program as “the model for every true Communist” (ibid, p. 39). This confusion suggests a continuity with the Nazi past that, so long as it remains unaddressed, will continue to contaminate the present and future.

Following Paul’s divorce, his son, Konny, builds a close relationship with his communist Grandmother. However, rather than view the victims of the Gustloff as victims of Nazism, he views the Communists as responsible for the ship’s destruction and suggests that Germans are forced to deny their own victimization as a part of a “world Jewish conspiracy that aims to pillory us Germans for all eternity” (ibid. p. 76). Konny, in a sense, returns to a pre-GDR sense of German victimization. Paul, in his narration says, “He [Konny] is calling for distant memories” and the sense that “Time passes”. (ibid. p. 71). However, despite the passage of time, all three in the familial triad are stunted, unable to move past this event even after the defeat of Nazism and the victory of German liberalism over communism resulting in Unification.

The Pokriefkes stand suspended in moral and ideological space within a country engaged in rapid progression. This sense of arrested development finds expression in the novel’s main image of the crab. Early in the novel Paul says: “Should I do as I was taught and unpack one life at a time, in order, or do I have to sneak up on time in a crabwalk, seeming to go backward, but actually scuttling sideways, and thereby working my way forward fairly rapidly?” (p. 3) Paul intellectually understands the nature of journalistic and archival work and throughout the novel “showers” the reader “with statistics” regarding the Gustloff’s tragic end (6). However, this intellectual account of the event ironically distances him from those in his own life who use this event as a substitute for meaning in their lives.

Consequently, Paul’s reporting and acknowledgment of his son’s Nazism does not prevent Konny from killing a friendly rival he makes online who impersonates David Frankfurter, Gustloff’s Jewish assassin. During an outing, the two online compatriots, approach an abandoned statue of Gustloff, causing “David” to spit on the statue. Konny responds by producing a pistol, killing his rival.

In the aftermath of this shooting, Paul, and therefore the reader, learns that “David” was actually a gentile named Wolfgang Stremplin. Learning this fact during Konny’s subsequent murder trial enrages Tulla, who slides into an East German accent, declaring, “What a windle! How was my Konradchen supposed to know that this David was a fake Yid? So he was fooling himself and other folks, present himself all the time as a real Yid and going on and on about our guilt…” (p. 195)

Old habits die hard in Grass’s novel – while Konny is found guilty, Paul visits him in prison and learns that while Konny ostensibly denounces Nazis, other Neo-Nazis have dedicated a virtual memorial to him in the vein of Konny’s own website memorializing Gustloff. Paul laments in the novel’s final words: “It doesn’t end. Never will it end” (234).

Grass’s depiction of ideological extremism at first blush appears a defense of “sensible liberalism” in opposition to left and right-wing violence. While Grass did oppose political violence on the left, the experience of the post-war era left Grass skeptical of the efficacy of liberalism to prevent it. Dubbing the 1980s “Orwell’s decade,” Grass criticized the West German government sharply for its complacency in international affairs and commitment to American “containment” policies. In other words, the “moderates” of West Germany, despite their adherence to anti-violence ideology, did not take the broader peace movement seriously. Much violence still occurred in Western European society, but under the guise of “peace-keeping” and, during the period of German reunification, “reconciliation.”

To Grass, the traumatic experiences of those displaced after the War was swept under the rug, ignored in order to promote a narrative of German guilt for the Holocaust. While Grass famously advanced this narrative, to the point where he believed German unification was unachievable and undesirable as “punishment” for the Shoah, he also accepted the anger of Germans towards society as valid and in need of redress. However, Grass too acknowledged that the space of this reconciliation could not be merely political or economic as he viewed the case to be with reunification. Rather, as explicated in Crabwalk, this reconciliation must be temporal as well, worked out in the field of memory politics.

Thus, rather than focusing on the mere presence of extremist ideologies, Grass contends that constant changeovers in political power within a short period of time puts the ordered existence theoretically provided by nation-states out of reach of those who actually live in them. Benedict Anderson, the famous historian of nationalism, argues that the shift in consciousness associated with the “national revolution” of the early 19th century, occurs temporally rather than merely spatially. The experience of “meanwhile,” and the idea that thousands, if not millions, of “conationals” occupy this same spatio-temporal political space as coequals before the law provides the humus that creates national orders. However, with the distortions of this temporal balance, comes disorder and fluxes in identity. In the case of Germany, the collapse of Weimar and the rise of Nazism, the partition of Germany, and its subsequent reunification and East-West inequalities, create a sense that “Germany” as a concept will always struggle to define itself in relation to its neighbors. By extension, Grass was fond of pointing out that event the first “unification” was a failed event.

In applying this novel’s concept to the American case, it would be easy and ideologically convenient to pin the resurgence of 20th century ideologies to the rise of Donald Trump and call it a day. But this reading would flatten the traumatic experience felt by many Americans during the Cold War. As Hannah Arendt points out in her work, “On Violence,” those born in the decades following the Second World War were taught as a matter of fact that their existence could be ended or jeopardized at any point by the threat of a nuclear USSR. It is not creative nor difficult to draw a line between the bomb drills experienced by the children of the 50s and 60s to the “active shooter drills” inflicted upon the children of today.

One must remember that Donald Trump, the self-appointed “voice” of the “forgotten man of history” also experienced the twentieth century in America. The United States has not seen as many ideological shifts as Germany has. Yet the Vietnam War, Watergate, the Kent State shooting, the rise of Reagan, the rise and fall of the welfare state, the Columbine High School massacre, 9/11, the War in Iraq, and the election of Donald Trump all occurred within what is essentially a lifetime, creating an atmosphere that constantly upends political memory. Events that normally galvanize a people and provide a sense of public order now flash in and out of consciousness quickly and without fanfare. While historical events have not ceased occurring, recognition of these events’ importance has. Since the end of the Cold War and the stagnation of the War on Terror, America’s violent tendencies have been focused inward. We see this in the way humanitarian dimension of the border crisis is lost during the subsequent debate regarding what the causes of or the proper nomenclature for the crisis are.

Rather than progressing towards an ideological goal, people in modern democracies appear “frozen” in history, unable to reflect upon the unceasing movement of modern politics. Far from representing a departure from our so-called “post-ideological” age, Trump may be the perfect crystallization of a century marked by trauma and injustice. In this sense, Grass’s plea to scuttle backwards in order to recover what has been lost in an age that “doesn’t end” is more important now than it was 17 years ago.

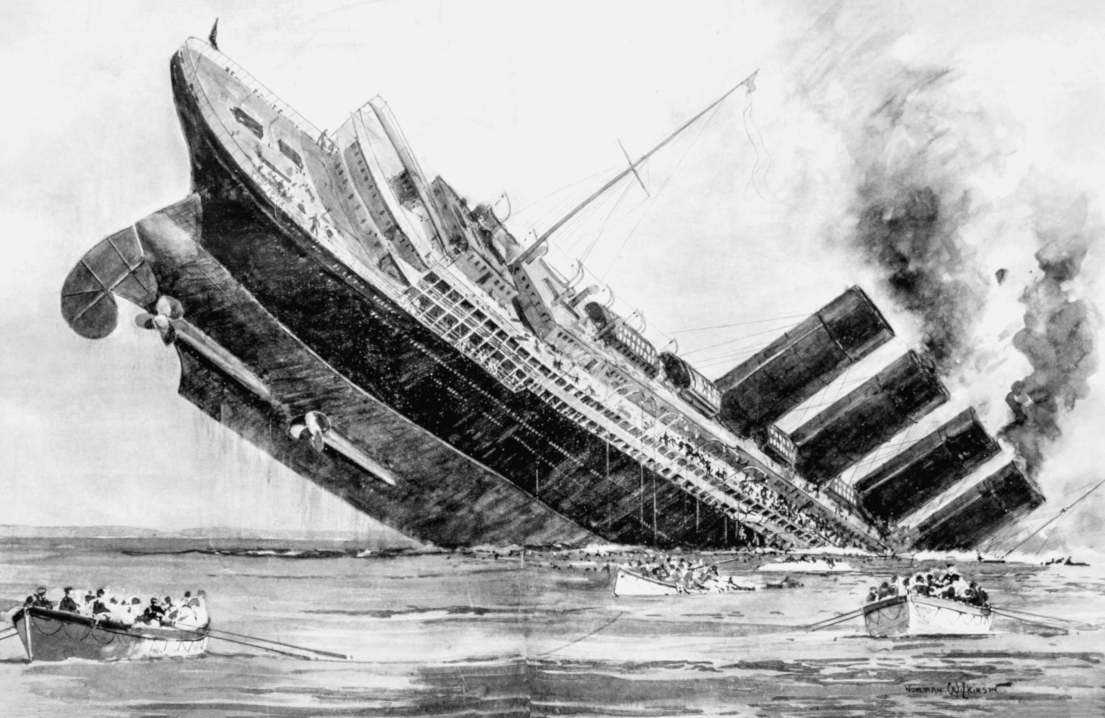

Featured image is The Sinking of the Lusitania, by The London Illustrated News