What Today’s Reformers Can Learn From the Temperance Movement

Before its more famous 20th century iteration, the temperance movement demonstrated the value of mass persuasion over force as a tool of cultural change.

At the time of the American Revolution, Americans drank a lot of alcohol. Alcohol consumption per capita was around three times what it is today. Even babies drank (for medicinal purposes).

But by the time of the Civil War, after several decades of temperance activism, if you were a respectable, upwardly-mobile American, you were almost certainly a teetotaler. Consumption rates plummeted. Half of all Americans quit drinking altogether (including many babies).

Sixty years after that, anti-alcohol forces achieved legislative nirvana—an unfathomable triumph in today’s political paralyzed context—a constitutional amendment banning the manufacture, transport, and sale of alcohol.

But just 14 years after that astounding success, it seemed everything the movement had pursued and won came crashing down, legislatively and culturally, with the repeal of Prohibition by another constitutional amendment.

Most Americans have probably never heard of the temperance movement—arguably the largest, longest, most successful reform movement in American history—or they conflate it with the later push for legislative Prohibition. But that’s not how things started. The 19th century temperance movement, which sought to convince Americans to stop drinking mostly through persuasion, had a spectacular, decades-long run before turning wholesale towards de jure Prohibition. The movement may have failed to fulfill its goal of eradicating alcohol from American life, but it succeeded in permanently and significantly reducing the nation's levels of alcohol consumption. Its imprint on American culture—and its lessons for those who seek to reform and influence culture in a free society—remains.

The early temperance movement

Long before the era of rum-runners, speakeasies, and moonshiners, the temperance movement persuaded millions of Americans to voluntarily quit drinking. Temperance began in pursuit of a larger utopians vision for society in the wake of the massive political, economic, and social changes—at once exhilarating and terrifying—unleashed by the American Revolution and the growth of an industrializing, market-based economy.

Temperance was one of a pantheon of antebellum reform and voluntary movements that sought to mitigate the potential downsides of these changes and harness them for good. Antebellum reform paired well with an optimistic, post-millennial form of Christianity emanating from the Great Awakenings that argued human beings could usher in Christ’s return through societal perfection. It seemed to many antebellum Americans that the United States might just be the vehicle to do that.

In the antebellum temperance mind, societal perfection began with self-improvement and self-mastery. Refraining from drink was an easy way for an ambitious man in a nation on the rise to be a more kindhearted father in the sentimentalized family, a more clear-headed worker in the industrializing work place, and a more moral and wise citizen in a democratic order that depended upon the virtue of its people. At scale, this individual betterment, reformers hoped, would create the ideal society. For temperance reformers in the movement’s heyday, “moral suasion,” not force of law, was the preferred strategy. However, even before the Civil War, the idea that the power of government might eradicate the great social evil of alcohol more efficiently began to have some appeal.

Temperance managed to span the great divides at the time over how far the utopian push for a perfected society needed to go and how much human equality should be involved. The movement spoke to the divergent impulses of societal liberation and societal control. Whether the ultimate goal was social order or social progress, a broad consensus of Americans, from radical abolitionists to some southern slaveholders, agreed that temperance was essential.

State power

The Civil War tamped down Americans’ optimism and resolved, in most minds at least, the issues of slavery and race. Reuniting the country and reestablishing order—especially racial order, in the wake of slavery’s end, between the new civil rights for Blacks everywhere, and an increase in immigration—became more important than the pursuit of societal perfection. Americans, North and South, were eager to paper over their differences and raise a glass of water together and to consider a more forceful government response to the problem of alcohol. The temperance movement increasingly slid toward prohibition.

The war redefined and reasserted the role of government, particularly the federal government, by forcefully quashing the claim that states could secede and by legally overruling their authority over individual civil rights (in theory—we’ll get back to you in about a century). A major antebellum reform movement, abolition, had achieved its goal through governmental power and law, and radical reformers after the war saw, correctly, that continued government intervention would be needed far into the future to make sure slavery didn’t return in some other guise.

Another development that pushed temperance towards Prohibition was a split in American Protestantism between modernists and fundamentalists that centered around biblical interpretation. This was in many ways a rehashing of the antebellum Protestant split over slavery, which similarly rested on divergent biblical interpretations, with southerners adhering to a more literalist one, but it also overlaid with a more national urban-rural divide. As the 19th century turned into the 20th, fundamentalists felt increasingly embattled in a modernizing, urbanizing, religiously and racially diversifying American culture and aimed at achieving greater political power to make up the difference. Prohibition was the perfect mechanism, it seemed.

For all these reasons, after the Civil War and heading into the Progressive Era, temperance reformers looked more and more to the law, to controlling American habits by force rather than through persuasion. The legal march started small, on the local level, with Sunday laws or other limited bans, then graduated to state legislation, before the Anti-Saloon League—the first single-issue pressure group in US political history and a pioneer of legislative lobbying—set its sights on a total, constitutional ban on the production and sale of alcohol.

Like the 19th century temperance movement, Prohibition rode both a progressive reformist wave that looked to government policy as the solution to social problems and a revanchist one consumed with anxiety over social change. Anti-German sentiment (German Americans brewed much of the alcohol in the US) during and after World War I greased the skids. Through this skillful, somewhat bifurcated appeal and incredibly good organization, the 18th amendment was ratified in 1919.

Prohibition was probably an overreach that was doomed to fail in any case, but the timing of its passage was particularly awful. Post-World War I, the growing numbers of urbane and urbanized Americans were in no mood for self-denial in the bubbly economic boom of the 1920s. The automobile and rising college attendance gave young people new found freedom. Women got the right to vote and demanded more liberation, starting with their clothing and personal habits.

The amendment, which banned something that had been legal for centuries, was always going to be difficult to enforce, although some historians argue that prohibition did lead to a sharp decline in alcohol consumption (it's unclear how much illicit behavior the data they cite captured). The law's failure to establish clear lines between federal and state authority didn’t help. Organized crime filled the demand and expanded the assault on law and order more generally. But the Depression ultimately finished off Prohibition. The government needed the tax revenue, and the economy needed every boost it could get. Prohibition was repealed by the 21st amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1933.

Legal prohibition may not have lasted, but there's a strong case to be made that temperance remains an overwhelming success. Americans' alcohol consumption has never again approached the levels before the movement began, and outside sub-cultural pockets of binge-drinking (among college students, for example), drinking in moderation is the accepted social norm. The more recent campaign against drunk driving has further influenced cultural practice. Groups like Alcoholic Anonymous—which is a direct descendent of the antebellum Washingtonian movement—are well known fixtures with millions of adherents from all walks of life.

Lessons for today

The 21st century is obviously very different from the 19th century as relates to social and political movements. There are few issue-based reform efforts that don't get subsumed under our two-party political system, which is increasingly overlaid with a two-tribe culture. And persuading people in an era of rampant disinformation within an overall blizzard of information seems like an herculean task. Still, in our time of intense culture war, when seemingly everything is contested, it's worth asking how the temperance movement changed American society and what lessons it holds for movements seeking change in our own time.

In terms of strategy, modern day reform movements of all kinds seem to gravitate toward law. But the temperance movement suggests that while persuasion is more arduous for bringing social change, the results are usually more durable. Is it more efficient to make people do what you want rather than convincing them to do it on their own? Absolutely. And sometimes the force of law is necessary, particularly to protect the fundamental rights of those in the minority. But for producing long term cultural change, it is better to help people choose the change for themselves. Of course, you could argue that people did choose Prohibition, in that a constitutional amendment was ratified, no casual walk in the park. American majorities continued to vote for dry candidates in the 1920s. But the end results demonstrate that most Americans wanted Prohibition more in the abstract. They probably supported it because a century of temperance work had led them to believe they should and/or it was associated with other cultural markers (i.e. If you were a nice white Christian, you were pro-dry).

In addition, the temperance and Prohibition story indicates that the downsides of legal reform are particularly acute when outlawing something that has long been legal. Enforcement of laws that roll back freedoms pushes government into potentially more authoritarian practices that make even theoretical supporters of the legal changes queasy, while non-enforcement risks undermining government’s credibility and encouraging lawlessness, as Prohibition demonstrated. Again, sometimes enhanced governmental power is necessary to protect the basic rights of citizens. Slavery and Jim Crow had to be outlawed, and enforcing those changes where they were deeply unpopular required massive governmental intervention. Federal troops occupied the South for a decade after the Civil War, and when they left, racial oppression was restored. Federal force was required again during the civil rights movement, which ultimately succeeded through cultural change as well.

In its messaging, the temperance movement demonstrated that while stoking fear and dread is an effective motivator in the short run, marrying a cause to a positive, uplifting vision that benefits the common good creates more enduring reform. While the temperance movement did use plenty of scare tactics in is messaging—for example, that taking even one sip of alcohol could completely unravel a life—temperance at its best propagated a message of self-improvement and societal betterment. Antebellum temperance reformers usually supported many other causes along these lines, from criminal justice reform to improved conditions in insane asylums to diet reform to the more radical causes of women's suffrage and abolition. This contrasted with what came later, when Prohibition was increasingly identified with the political goals of a particular religious subculture even as their overall beliefs and practices declined in popularity.

Whether scaring people or inspiring them, temperance reformers told more stories than they presented facts. Temperance literature, which included both fiction and testimonials, was voluminous, pervasive, repetitive, and affecting. Americans connected on an emotional level with men whose fortunes and families were destroyed by drink, their wives and children left vulnerable, as well as their rehabilitation through community support and encouragement. Reformers occasionally presented "facts" of sorts, although data collection wasn't great back then. But modern social science research indicates most people don't find such information as compelling as a human story with which they can identify. The temperance movement excelled at storytelling.

In addition, the movement's stories and messaging proved flexible and malleable as it adapted to different audiences. The cause of temperance was translated into all manner of sub-cultural languages, in some cases contradictory ones. In the South, where it was less popular but still had significant support, temperance offered slaveholders greater mastery and control. Nativists used it to stoke opposition to immigrants, who tended to more heavily imbibe. In radical reform circles, freeing the country from alcohol was paired with freeing it from slavery. Black reformers like Frederick Douglass supported temperance as a path towards self-improvement that would evidence the full humanity of Black Americans. Feminists used temperance messaging to argue that women needed more legal protection from drunken men and the suffrage to outvote them, and anti-feminists urged men to quit drinking in order to protect their authority and dispel such arguments. The temperance tent was big indeed.

The successes and failures of two modern-day reform movements bear these lessons out as well. The enshrinement of gay marriage in Constitutional law was arguably won via cultural change first. If efforts to overturn Obergefell succeed at the Supreme Court, it will probably be met with popular revolt at this point, because gay marriage is overwhelmingly supported by Americans of all kinds, increasingly even those who are religious. The turnaround in public opinion on his issue was incredibly swift, due to the movement's effective messaging, which emphasized a broad-based belief in stable families and loving relationships and put storytelling and human connection front and center. Gay marriage extended freedoms afforded to others in society to more people instead of taking them away.

In contrast, the movement to end abortion has put all almost its eggs in the legal basket, even as the number of abortions has plummeted since 1973. Most Americans want abortion to be safe, legal, and rare, a big-tent goal the pro-life movement might have joined via support for expanded healthcare and a stronger social safety net for mothers and children, to the public relations benefit of the movement's conservative Christian base. Instead, much like the forces of Prohibition, the pro-life cause has become strongly identified with the narrow political goals and religious beliefs of an increasingly marginalized evangelical subculture. Ironically but perhaps predictably, the pro-life movement's greatest legal success, the Dobbs decision, is already becoming its worst cultural failure. Not only is the abortion rate inching back up, but support for abortion rights appears to be strengthening even in some red states. Outlawing abortion in practice, which has led to draconian policies in some states, has proved distasteful even to many Americans who once supported it in theory.

The goal of reforming behaviors and norms in a free society always straddles the edge of two-sided coin, one side utopian and the other paternalistic. There is a fine line between the aims of social betterment and social control. The temperance movement was successful in large part because it messaged both sides of that balance and appealed to a broad swath of people and motivations. But its enduring achievement—the reduction of Americans' alcohol consumption—was built on a compelling narrative of how people could adapt to and thrive in a rapidly changing society by voluntarily altering their habits. It spoke to the fears of the age, but it offered the hope that self-control might help one's ship weather the storm. That may or may not not have been true, but the belief that it was permanently changed the habits of a nation.

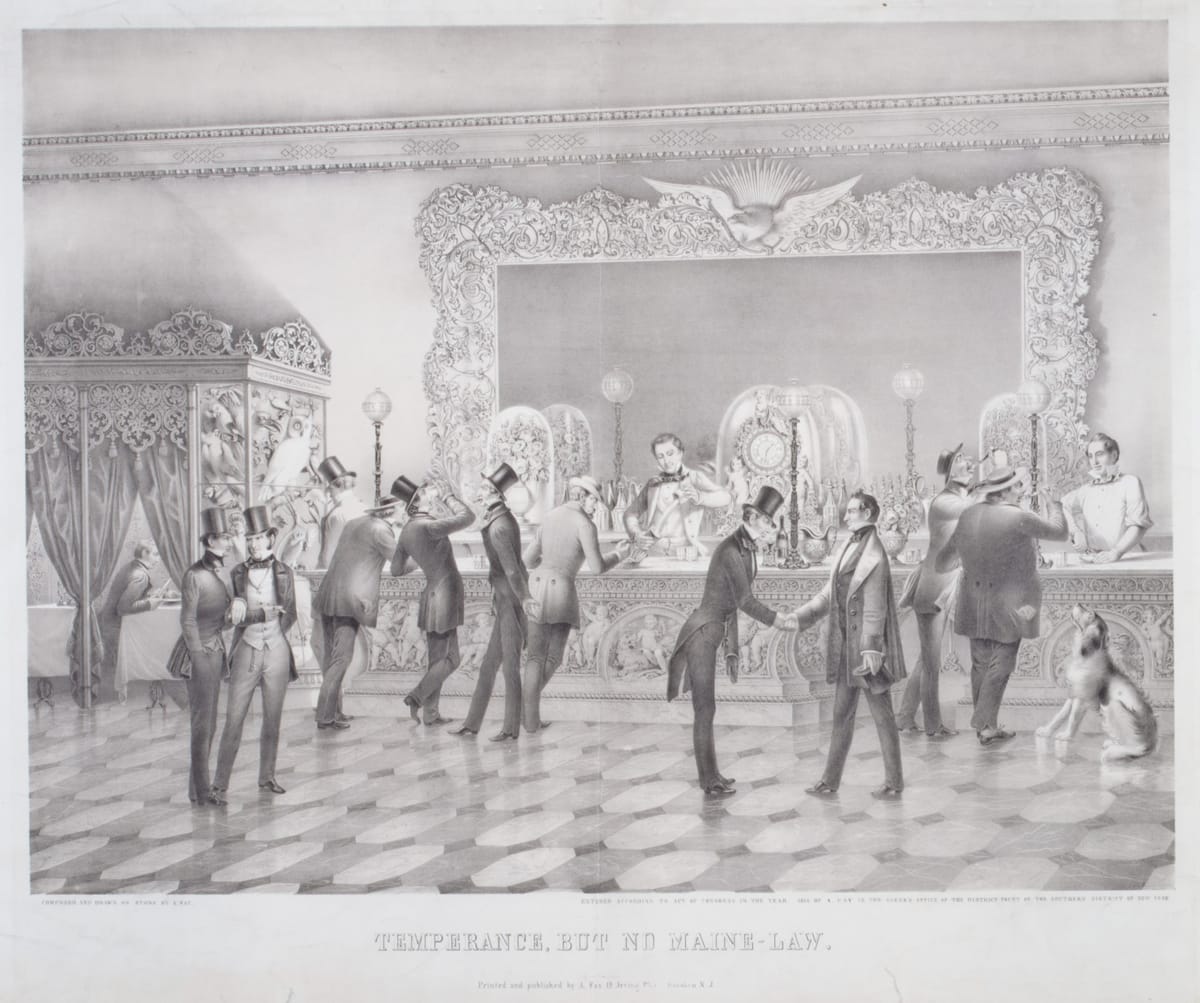

Featured image is "Temperance, but No Maine Law," August Fay 1854.