Who Owns the Founding? Akhil Reed Amar’s "Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution"

Amar's book is a useful history that nevertheless smooths over some of the real complexity of the eras it touches on.

Who owns the founding? For over two and a half centuries, nearly every one of the prominent men associated with the Declaration and Constitution have been claimed by warring political factions: the anti-bank Democrats of the 1830s, the antislavery Republicans of the 1850s and 1860s, the agrarians and populists of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the New Deal Democrats of the 1930s and 1940s. Almost without exception, American politics has been drenched in reverence for the founding generation, the men who built popular support for independence, bled to make said independence a reality, and rallied in Philadelphia to create what would become the longest existing Constitution in world history.

Akhil Reed Amar’s Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840–1920, the second tome in a planned trilogy on the history of the supreme law of the land, is an excellent portrayal of how that reverence shaped the political and legal battles of the most contentious epoch in American history. Amar, perhaps the most well-respected living scholar of American law, pays painstaking attention to how both the proponents and opponents of slavery, racial equality, and voting rights appealed to the values and principles of 1776 and 1787.

His central argument is that the titans of the period—such as Abraham Lincoln—were originalists, a term originally coined in the 20th century to describe a form of jurisprudence emphasizing the original intent of the Constitution and statutes. Traditionally (but not exclusively) a philosophy associated with conservative jurists like Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia, much of Amar’s work has been to rehabilitate originalism for liberal audiences. He frequently suggests that a sincere reading of the Constitution as originally written would lead to fewer conservative outcomes than right-wing originalists. At the heart of Born Equal, then, is a theory of American history that posits a direct link between the framers of the Constitution to opponents of slavery to contemporary liberals. Such a link, however, elides some of the complexity of the eras that Amar touches on.

“As much as any abolitionist”

Born Equal begins in 1840, when abolitionists and women’s rights activists were as fringe as political factions could be. The election that year was between Democrat Martin Van Buren, a “gifted politico” (Amar, 169) who “served pro-slavery forces” (Amar, 27) and William Henry Harrison, himself a southern slaveowner. Slavery was nowhere near as much an issue for voters as questions over the economy and western expansion. Insofar as it was an issue in the decade, slavery’s political opponents generally appealed to its deleterious effect on free white northerners without invoking the rights of slaves: “I have no squeamish sensitiveness upon the subject of slavery, no morbid sympathy for the slave,” said David Wilmot, namesake of the Wilmot Proviso which limited slavery in the new territories. “I plead the cause and the rights of White freemen.”

As pro-slavery forces overplayed their hand with the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Lecompton Constitution, and as writing and art depicting the horrors of slavery spread throughout the North, that began to change. The political opponents of slavery began to infuse abolitionist-lite rhetoric into their politics. The nascent Republican Party, founded in opposition to a Democratic plot to allow free white men in northern territories to permit slavery there, was led by men like Abraham Lincoln, who would unashamedly declare that he had “always hated slavery, I think as much as any Abolitionist.”

It wasn’t until Southern secession and Union victory in the Civil War, Amar recounts, that Republicans would embrace full abolition and civil rights for Black Americans. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were a complete legal and social revolution. The first eradicated slavery, which had just ignited a war that left hundreds of thousands of Americans dead, the second enshrined civil rights for Black Americans and guaranteed citizenship for everyone born on American soil, and the third guaranteed the right to vote for Black men. Never before had changes this monumental happened in such little time—the Thirteenth amendment was ratified in 1865, the Fifteenth 1870.

“No property in man”

The throughline of Born Equal is the reverence ordinary men and women had for the founding generation. Amar cites countless examples of this: the first five presidents were Founding Fathers, the sixth, the son of one; every major party platform until the 1860s referenced the Constitution and half referenced the Declaration; supporters of proscribing slavery in the new territories pointed to the founding generation’s decision to do the same; descendants of the founders frequently attained high political office; women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton bemoaned that immigrants and newly freed slaves would enjoy suffrage before the “daughters of Jefferson.” Amar’s America is one utterly obsessed with decoding and depicting the founders, hailing their character and accomplishments and downplaying their faults.

You cannot understand Republican opposition to slavery, for instance, without also understanding just how they viewed the Constitution’s relationship to slavery. How can anyone sincerely square their opposition to slavery with fidelity to the Constitution, defenders of the particular institution asked. The Constitution expressly mandates that states—even free ones!—return fugitive slaves. It counts slaves as 3/5 that of free persons, an enormous boost to the political clout of the South that Amar notes would prove pivotal in several votes (including the election of 1800, which Jefferson would not have won had slaves not been counted in the Census). James Madison, father of the Constitution, was a slaveowner, as was George Washington, John Jay, and several of the other delegates to the Constitutional Convention.

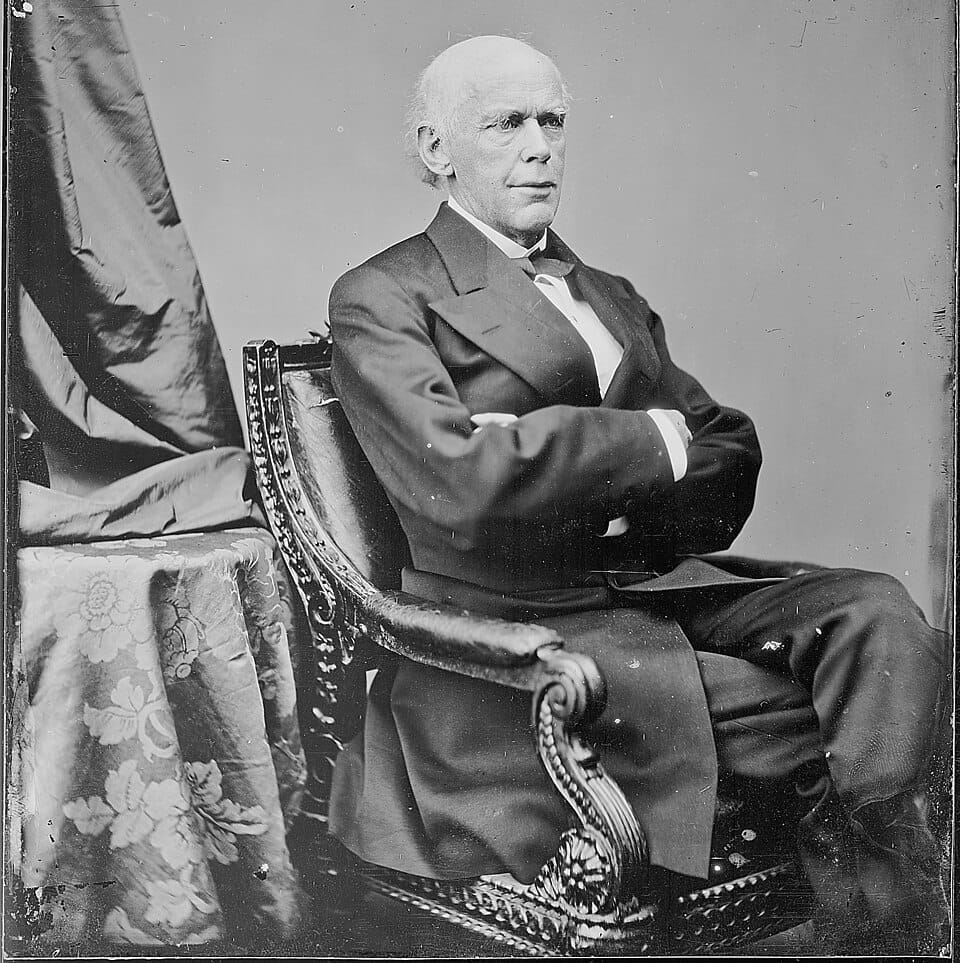

The answer, men like Salmon P. Chase and Abraham Lincoln retorted, is that the Founders did oppose slavery, and not just on pragmatic but also on moral grounds. The Fugitive Slave and 3/5 Clauses were merely concessions a mostly antislavery group had to grant to Southern delegates to ensure they would not bolt. The founders overwhelmingly supported prohibiting slavery in the Northwest territories, and James Madison would ensure that the document would not countenance “property in man” (Amar notes, as other scholars have, that the words “slave” and “slavery” are nowhere in the Constitution.). Regardless of their faults, Republicans argued, the Founders in essence had the same position that they did: not total abolition, but restricting slavery enough that it can be said to be on the path of “ultimate extinction.”

The Declaration of Independence, Amar writes, is also the subject of enormous attention by politicos and regular people alike. Its preamble is quoted ad nauseam by Lincoln and his fellow Republicans, who cite it to maintain that slavery is inimical with the very principles that birthed America. It was this very insistence, Amar writes, that “would eventually vault this man, a relative unknown, into the presidency” (Amar, 304). A nation in love with the Founding would fall in love with a man who championed its ideals more than any other, a self-made parvenu whose dedication to the proposition that all men are created equal would cost him his life.

“Liberal principles”

Amar’s recounting of how those fighting for abolition and women’s suffrage appealed to higher-order principles of equality enshrined in our founding texts is insightful and instructive. In his odes to the men and women who supported limiting slavery and establishing Black rights in the antebellum and Reconstruction eras, though, there is perhaps too clean a line being drawn between them and modern liberals. The electoral coalitions of the 19th century are close to incomprehensible to modern readers.

For instance, the Democratic Party, which had spent the antebellum period transmogrifying into the country’s premier defender of human bondage, was also the party with what we would now consider a far more enlightened and liberal view of immigration. Amar quotes from their 1848 platform:

“The liberal principles embodied by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, and sanctioned in the Constitution, which makes ours the land of liberty, and the asylum of the oppressed of every nation, have ever been cardinal principles in the Democratic faith, and every attempt to abridge the present privilege of becoming citizens and the owners of soil among us, ought to be resisted with the same spirit which swept the alien and sedition laws from our statute book.”

As the United States underwent a remarkable demographic transformation, with millions of Europeans coming to America seeking a better life, many of those fighting to maintain and expand a system that treated Black men, women, and children as property sought to protect the rights of would-be Americans. Nativists who were hostile to this change fled to the new Know-Nothing Party (and to a lesser extent, the Republicans). It wouldn’t be accurate to call the antebellum GOP an engine of nativism, but a major strand of it—including members who fought valiantly against slavery—saw the increasing number of foreigners entering the United States and becoming citizens as a major threat. In fact, many of them saw the slave power and Catholic immigrants as part and parcel of the same mission. Historian William Gienapp explains:

“During the senatorial contest between Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas in 1858, the Republican state organ, the Illinois State Journal, in an editorial titled "The Two Despotisms-Catholicism and Slavery-Their Union and Identity," charged that the Catholic church was in league with the proslavery Democratic party to destroy the principles of free government. Throughout the 1850s and well beyond, the Republican party projected an anti-Catholic image, a fact readily perceived by both nativist and Catholic voters alike. Indeed, the presence of Catholics normally increased Republican support among both Yankee and German Protestant voters. Certainly, many Republicans were indifferent to the party's anti-Catholicism, and it never was the focus of the party's ideology, but for many others it was a very important element in their loyalty to the party” (Gienapp, 548).

The Grand Old Party, whose support rested largely on Yankee settlers in the midwest and native-born farmers in New England and the mid-atlantic, was not as receptive to the polyglot immigrants arriving from Ireland, Germany, and Sweden (especially Catholic immigrants). Amar's book is largely about Republican reverence for the founding generation, but he rarely notes just how important an ancestral connection to the Founders was to these men (Abraham Lincoln being a notable exception). If one seeks a historical precursor to modern liberals’ belief in pluralism and religious tolerance, they should look to the party of Franklin Pierce, not their opposition.

Amar portrays Republicans as men incensed by the moral abomination of slavery, carried into elected office by increased Northern misgivings with the peculiar institution. This is largely true—but they were also a political party, bound by public opinion and motivated by the same fears and resentments that had guided Americans at the time. Their political success cannot be attributed solely to high-minded appeals to the Declaration’s egalitarian principles, and the politics of the antebellum period cannot be understood without fully grasping these competing notions of liberalism.

Bibliography

Amar, Akhil. Born Equal: Remaking America's Constitution, 1840–1920. New York: Basic Books, 2025.

Wilmot, David. “I Plead the Cause of White Freemen.” 1847.

Gienapp, William. “Nativism and the Creation of a Republican Majority in the North before the Civil War.” The Journal of American History, Vol. 72, No. 3 (1985): 529-559

Featured image is Hon. Salmon P. Chase, Chief Justice U.S