Why We Need a Reconstruction of the Liberal Public Sphere

How media systems work, how ours came to be, and where we go from here.

In early April last year, during a visit with someone important to me, the topic turned to politics. Neither of us is shy about getting into these things with one another, and never have been. Over time I have grown more selective about which battles I pick, but in this case I thought I was picking a relatively easy one: the January 6 insurrection. After all, I remembered what he had said at the time, which was an unqualified denunciation of what was, in his words, Donald Trump inciting a riot. I assumed our disagreement was going to merely be over whether it was wise to prosecute Trump.

I was wrong. Saying that he had simply been misled by the media initially, that with information we’ve learned since he’d come to change his view, he completely dismissed the significance of the events of January 6 as anything but a propaganda coup for Trump’s opposition due to the optics of it. The “only person who was killed” was “on the protesters’ side,” and therefore any supposed danger the “protesters” posed, or the laws they broke, could be dismissed. The relentless physical assaults on law enforcement at the scene went unmentioned (never mind the circumstances under which the “person who was killed” was shot). And “it isn’t as though Trump said to do an insurrection.” This is, of course, the kind of logic you see with Holocaust denial and other saying-it-but-not-quite-saying it rhetorical games. Indeed, outright dictators mocking the weakness of democracy never actually say that their own country is not one, instead they speak in euphemisms about “the West” or simply “liberalism.”

I felt I had run full sprint into a brick wall I had not even seen in front of my face. How could one of the most documented and investigated events of our times be understood so radically differently? My interlocutor has a graduate degree, is allergic to television news, has therefore never been a Fox News or OANN viewer, and spent his decades-long career studying media. He is very much someone who should know better. How could this have happened?

The fracturing of our media world and the consequential fracturing of our collective perspectives is the key phenomena behind so many things that have gone wrong in our times. Vaccine hesitancy is the highest it has been in generations. A nontrivial number of conservatives believe that the Democratic Party is tied to child trafficking. And in a year in which unemployment was low, pay was good, and savings were up, perception of the economy was abysmal.

Each of these facts accounts, in part, for Donald Trump’s successful return to the White House. But I cannot help but think of January 6, and the ways it is now understood, as the most pivotal. On that day, and on January 7, and even for most of the week after, America stood more or less united in our horror at and interpretation of what had happened. No man responsible for what happened that day should ever have stood a chance in politics again.

Yet not only did he stand a chance, he took 76 percent of votes in the Republican primary and went on to obtain three million more votes than he ever had in a general election, securing his victory, his first where he actually won the popular vote. Disapproval of the events of January 6 have softened significantly in the polls, but for 77 million Americans to willingly pick the man behind it, the significance they give the event whether or not they disapprove of it must be rather low.

What role did media play in this outcome? It is a hotly debated topic, ranging from those who wish to give it near-total responsibility and those who wish instead to explain things in terms of “material conditions”—the actual quality of life of voters, from which something like the January 6 insurrection is quite remote.

Media matters—how could it not? It is the means through which we obtain not only information, but interpretations of that information. For a species sociologically determined to observe one another and observe ourselves being observed, social media and digital communications channels in general must surely play a role in shaping our publics as well.

I will not put a number on the magnitude of the effect particular choices made in our media last year impacted the election result. Instead I wish to explore the mechanisms by which media influences outcomes in society in general, as well as how the system in which those mechanisms are used has changed as technology has advanced.

A key mechanism by which media influences society is through the production of “reflective beliefs,” which Henry Farrell defined as “something that you know you are supposed to believe, and publicly affirm that you believe but might or might not subscribe to personally.” Media systems produce communities of reflective beliefs, groups of people that cohere around knowing what they are supposed to believe is the case, speaking and in some cases even acting as if they truly believe it, regardless of whether or not they harbor any private doubts or outright disbelief.

In the pre-broadcast, pre-telegram world, newspapers produced very local communities of reflective beliefs. The era where a handful of broadcast television channels enjoyed audiences composed of large supermajorities of the nation’s population produced nation-sized, very cohesive communities of reflective beliefs. And the Internet era has created a vast array of such communities, varying in size from dozens to tens of millions or more, and varying in geographic spread from very local to very global—with the very small groups just as likely to be national or global in spread as they are to be local.

We will look at each of these systems in turn, the technologies that determine their basic structure, and the historical contingencies that might have gone differently. We will begin by looking at the mechanisms that form the building blocks of any media system.

Formats

When we speak of media, we are often being relatively specific—a printed newspaper, a painting, a TV show. To begin to appreciate the power of any of these, however, it is useful to speak of formats in general—text, image, audio, and video.

It would not be oversimplifying to say that that list runs in order of social potency, with text as the least potent and video as the most.

Consider the difference between the Ferguson protests in 2014 and the George Floyd protests in 2020. The latter are quite like January 6 in their history—achieving, in the beginning, a level of national unity that is quite rare, but ultimately fragmenting into mutually contradictory narratives held by mutually hostile groups. In the case of Ferguson, however, fragmentation was established from the start.

What made the difference? There are probably a few factors that went into it, including just how brazen the murder of George Floyd was compared to the ambiguity of the particulars leading to Michael Brown’s death, but even here, the fact that there was a video in one and not in the other is critical.

Even if the specifics of Brown’s death had been established from the start—even if the police themselves, politicians, journalists, and medical examiners all swore that matters unfolded exactly as one-sidedly as they did in Floyd’s case—in the absence of a video, it’s highly unlikely it would have played out the way the George Floyd protests did.

Text demands some work on the part of the reader, some attention and effort at understanding. This is less so for, say, a social media post that is just a short sentence than it is for an article. But describing Brown’s death takes an article. Indeed, a detailed description—aimed at leaving no doubt about how things happened and why—is more demanding than the average news article.

By contrast, even a ten minute video is not much effort for the viewer. Nine minutes was a terribly long time for someone to have their air cut off, but to a viewer, each second that passes where Floyd could not breathe feels like an eternity, every minute hammering in that this is too long. People didn’t need to watch the full video to grasp what had occurred, and text covering the incident only solidified the conviction the video produced that Floyd had been summarily executed. Even that old cynic Mitch McConnell, whose relationship with the truth is dodgy at best, said plainly:

In no world whatsoever should arresting a man for an alleged minor infraction involve a police officer putting his knee on the man’s neck for nine minutes while he cries out ‘I can’t breathe’ and then goes silent.

Video is by far the most potent format, for the experience of it comes closest to the experience of being an observer to something in our everyday life, the kind of experience we process as a matter of course. Viewing a video and understanding what we have viewed requires as little effort to understand as any format developed so far. When broadcast television came into its own, studies determined that audiences treated it as a substitute for print rather than a complement, though newspapers of course did continue to exist alongside television. Audiences very naturally flock to video compared to other formats.

Video has existed for barely more than a century and in many ways we are still living out the social consequences of it. For of course, the technology has developed enormously in that short time. What once required enormous capital investments is now available, at surprisingly high quality, to the average person in the world, never mind the average person in a rich country like ours.

We’ll do it live

When it comes to the manner in which media is consumed, the biggest question is not “paper or digital?” nor “broadcast or cable?” but “live or not?” There is live, synchronous media, and then there is asynchronous media. The gulf between them and their effects is quite large.

The political scientist Naunihal Singh argued that broadcast in particular had the ability to produce “public information, claims and statements that are common knowledge for members of the target audience.” This is because “A broadcast is not only heard by everyone, but everybody knows that everybody else has heard it, and everybody knows that everybody knows that everybody has heard it, ad infinitum.” (Singh 2014, 28)

The quality that Singh emphasizes is not unique to broadcast but is true of live media in general. Audiences for live media, and especially live video, have a kind of mutual awareness that creates the conditions for Singh’s public information. Singh discovered that this effect is so potent that it can lead to a successful coup even in the absence of hard military power on the part of the challengers, or the reverse—to defeat a coup attempt by those who do have military power on their side. This comes down to the way perceptions of power and the reality of power are often one and the same thing.

When asking whether it is a fact or not that a coup has succeeded, the answer comes down to whether or not enough members of the military believe it has succeeded. As such winning is less a matter of persuading individual military leaders that they should join your cause as it is persuading them that the other military leaders already have joined your cause. This is because the strategic structure of coups is what’s known as a coordination game, where the only way to lose is to fail to bandwagon to the same choice as everyone else. If you can persuade enough people that you have already won or that your victory is inevitable, you can, in Singh’s terminology, “make a fact,” create the fact of your victory through the management of perceptions. (Singh 2014, 22)

The reflective beliefs discussed above—beliefs about what you are supposed to believe—are just the sort of “fact” that live media is in the strongest position to “make.” After viewing the evening news, viewers come away with a strong impression of what other viewers likely believe they’re supposed to believe about the topics that were covered.

Asynchronous media simply does not have this kind of potency. Text can be read at any time or not at all by those who have it, and even if you know a lot of other people have it too, you cannot be sure if or what they have read. For example, if the text is a bundle of things to read, such as a newspaper, it could be that you have read one article that most other readers passed over in favor of others. The recursive logic of mutual perception required to create public information is much harder to produce than for live media of all kinds, and especially live video.

Still, it can be done. After all, the Revolutionary generation mobilized against the British on that basis. That era had its ways of producing public information locally. For example, broadsides with simple, sensational messages were distributed in highly trafficked public squares. When there were very few local newspapers, and they didn’t have video to compete with, it was safe to assume that many others in your community were reading most of the same articles that you were, and the front page in particular was capable of producing public information. And of course, just as word of mouth can spread rumors and gossip, it can also spread mutual awareness that a large number of people have read the same stories.

Today, text can approach a synchronous experience with rapidly updating social media feeds during currently breaking events. I have personally experienced events from the Boston lockdown in the manhunt for the Tsarnaev brothers, to January 6 itself, to the recent attempted coup in South Korea, through social media feeds. Of course, posts on these feeds include pictures and short videos, but commentary and discussion on the platform itself is in text, and the rapid fire replies and conversations occur mostly in text as well. This near-synchronicity does not even require a news event; sometimes random topics become the topic of discussion among a segment of a platform. This past week has seen a large and loud segment of Bluesky users relitigating interpretations of the Star Wars prequels as well as reacting to Ross Douthat’s atrocious softball interview with a fascist, for example.

Rapid technological change

For the first century or so of American history, the fastest speed of travel, by ship, was quite slow compared to today, and communication moved at the same speed as physical objects. “Media” was simply print and the only competitor for attention were live performances, which by their nature were far more geographically constrained. After all, you could print up a lot of copies of a newspaper and send them off to nearby towns. There was no copying a live performance; it happened in one place at one time.

With the development of the telegraph, communication speeds exceeded transit speeds, allowing for greater national integration in a number of ways. Still, public-facing media remained primarily local, even in the era of the great media magnates like William Randolph Hearst, who grew his empire to an audience of twenty million at a time when the total population of the United States was at or under one hundred million. He accomplished this feat by having numerous papers in cities across the country, each with their own discrete, local audiences.

Gluing these local publications together somewhat (beyond media conglomerates like Hearst’s) were the syndicates, which would sell content (articles or cartoons) to multiple papers across the country. Through syndicates, and through media barons like Hearst, the country began to take steps towards the nationalization of media ownership and the production and distribution of content, but overall the system was still quite decentralized, and audiences were entirely so.

Radio, when it first came, was quite decentralized at first, too, with entirely local stations each running their own unique programming. Even television followed that model to begin with. But eventually, by the ‘60s and the ‘70s, audiences became national.

Although the publics were much larger than the print ones, the market was not actually more competitive. The era was dominated by what was known as the Big Three networks—CBS, NBC, and ABC. These three alone reached extremely concentrated national audiences. In their heyday, some 70 million viewers—about 30 percent of the total population—tuned in to the news each evening on one of the Big Three.

The Big Three’s moment did not last long. On the scale of human history, it seems a bit absurd to call it an “era” at all. By one account, the Big Three held more than 90 percent of prime time audiences in the late 1970s. By 1989 that was down to 67 percent, and it continued to drop from there. What happened? Simply put, the options available expanded, slowly at first and then dramatically.

Here’s one estimate of the average number of channels available per US household with a TV set, by decade:

By 1990 the Big Three faced what to them would have certainly seemed like a very competitive field, but still between the three of them they held a supermajority of prime time audiences. Things escalated quite drastically from there, particularly as the adoption of cable TV spread across the country and cable providers invested gains from those adoptions into bringing in more cable-only channels.

In the realm of news, the beginning of 24 hour cable news channels like CNN in the 1990s is often blamed for eroding the reach of traditional broadcast news, but this is wrong. Even now, the cumulative prime time audience for cable news is smaller than the equivalent for traditional broadcast news (roughly 3 million vs roughly 19 million). Indeed, all live, prime time TV news audiences combined do not come close to the absolute size of the Big Three era audiences—back when the population of the country was about 40 percent smaller!

Cable news did not kill broadcast news. Non-news content, competing in the same time slots as TV news, devoured the latter’s audiences. It turns out that once you offer TV entertainment at the same time as TV news, most people choose entertainment, even those who might have chosen TV news over print entertainment.

Expanding the number of channels also means fewer and fewer people are watching the same things, though even in the media system of the ‘90s the big hits were quite big compared to today.

But the biggest radical change comes with the tremendous openness introduced by the adoption of the Internet. Parallel to this was the development of “desktop publishing,” affordable personal cameras for pictures and video, and audio recorders. As these technologies became cheaper, more widely adopted, and higher quality, the number of potential competitors to professional media exploded. The boundaries between producers and audience went from being a stark line to a spectrum, as ordinary people intending to post for their dozens of friends and family have the potential to go viral and reach audiences of tens of millions, or more. The probability of this happening to you personally is quite low, but the probability of it happening to someone today is almost a certainty. The radical openness and virality of today’s Internet is constantly giving ordinary people audiences on par with content produced by major studios, even if in the lion’s share of cases this is merely fifteen minutes of fame.

Another thing that the Internet did was bring a potentially national, and indeed even global, reach to all formats. Throughout the period of broadcast dominance, newspapers remained local in their audiences. Even the New York Times or the Washington Post, with their national reputations, relied overwhelmingly on local subscribers and local classifieds for the business. Other print markets, such as magazines and especially books, were more national in their audiences, but these audiences were quite small compared to television’s.

Local print news survived the adoption of broadcast and cable just fine. When the Internet suddenly allowed the New York Times to absorb as much of the country’s audience for written news as would have them, and sites like Craigslist could independently absorb the entire country’s classified ads, local print news around the country began to die off by the thousands. Those that remain are much diminished, save for a handful, who may not have done as well as the Times, but have managed to secure a large and durable enough subscriber base.

Media systems and society

Putting formats, manner of consumption, and technology together, we are now in a position to look at the different media systems formed from these ingredients, and the influence of these systems on society.

In his famous theory of nationalism, Benedict Anderson credited “print capitalism” with the origin of the nation-state (Anderson 2016, 41-47). In the world of the Founding Fathers, making something “national” out of the many fragmentary, local media communities was an active effort managed by a fairly well-integrated elite. Prolific letter writing and frequent personal travel were requirements for membership in this elite, and community-building among them was chiefly of this interpersonal nature. Through their efforts, they managed to produce recognizably national debates and movements, but from our vantage point the overall system was still quite scattered and decentralized. Reflective beliefs were still first and foremost formed one local community at a time, with meaningful variation among them.

By the era of Hearst, when transit speeds had increased by leaps and bounds, and wide adoption of the telegraph allowed for a decent segment of people to enjoy the benefits of rapid communication across long distances, things lurched in the direction of greater national integration. Yet with public-facing media still so local in nature, the communities of reflective beliefs remained chiefly local as well. As in the Founding era, elite communities of reflective belief outran the population as a whole in terms of integration across a greater geographic area.

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the heyday of the Big Three networks, broadcast media became truly national, and produced an almost singular community of reflective beliefs. The combination of large audiences, few channels, and synchronous viewing was incredibly powerful. Viewers of the evening news in the Big Three era felt that they could become informed citizens after investing less than thirty minutes of their time on it. And the signs that this was the case were all around them, as most of the people they would interact with at work or elsewhere had either watched or heard about the exact same broadcast.

The nationalization of the media had big implications for politics. Local problems where adversaries had locked into a seemingly unbreakable equilibrium could get shaken up by media savvy groups who could draw national attention. Indeed, this was the chief strategy of the Civil Rights Movement, and arguably the central cause for the lion’s share of its success.

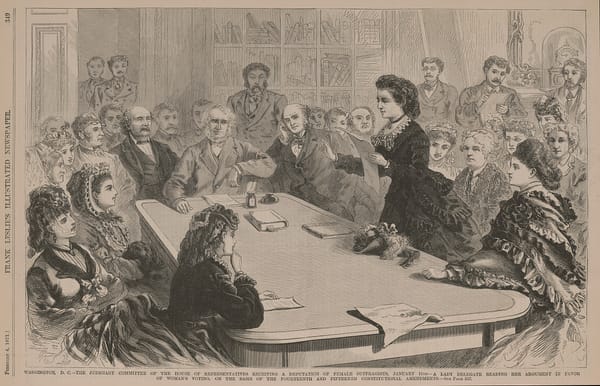

Consider the famous broadcast of the march from Selma, Alabama in 1965. ABC was having a larger than usual audience that evening because it was the television premiere of Judgment at Nuremberg, which had a star-studded cast. When they chose to interrupt that broadcast with images of Civil Rights marchers being brutally beaten by the police, that broadcast reached an estimated audience of 48 million, or about 24 percent of the total population of America at the time.

The Selma broadcast very likely gave us the Voting Rights Act. Perhaps we would have had it sooner or later, or in a slightly different form. Or perhaps not. Timing matters, as does manner. The Selma broadcast launched the VRA in a strong form with huge supermajority support in Congress and the general population. The events at Selma became public knowledge, and as much as the actual disapproval, the perception of broad disapproval gave powerful leverage to the people already seeking an edge in their confrontation with the Jim Crow regimes.

The Big Three were enormous, social reality-producing media institutions, and they worked in close partnership with the big knowledge-producing institutions (universities) as well as the government (through, among other things, the FCC). And so the era has, for those who look back on it from our times, a reputation for being uniquely conducive to propagating truth, science, and trust in authority. But they could just as easily foster resentment—even if your beliefs differed drastically from those you knew you were supposed to believe, even if you were a conservative or a radical living in the world that New Deal liberals made, you existed in the same shared social reality with others, like it or not.

And similar systems in other countries have been used quite effectively towards illiberal and dishonest ends. Imagine if a Trump figure came to power in that era and simply moved to take more direct control of the Big Three for the purposes of propaganda. We need not strain ourselves to imagine it; it happened over and over again throughout the world in the 20th century. And one implication of Naunihal Singh’s work on coups is that countries with Big Three-like systems are at far higher risk of having coup attempts succeed than those with a more fragmented media landscape.

The Big Three era was an anomaly in media history, a small window of time in which a handful of broadcasters held concentrated national audiences to themselves. Technologically, we simply cannot go back. Nor should we want to. Beyond those defects described above, there is something innately illiberal in the longing for the simplicity of the Big Three era. The very things that people miss about it—the potential for very broadly shared experiences produced by an extreme narrowness of options, providing a sense of thicker communal participation—are precisely what the communitarians and reactionaries wax poetic about when discussing their imagined pre-modern community, their gemeinschaft. So many words written and tears shed on behalf of the lost pre-modern way of life, so thicker with meaning, so purposeful compared to the hollow freedom of modern society (gesselschaft). If only we could go back, or if only we could approximate it. In the gemeinschaft, knowledge, morality, and purpose were all unified, they constituted the group.

So too for the lost world of the Big Three, and of 20th century mass broadcasting around the world. Emerging out of the relatively more complex system of loosely connected but highly local and decentralized print media, it produced a far simpler, more united whole, resting on a scarcity of options and on the scarcity of time itself, the few slots into which to put what few programs were produced, and especially that coveted prime time slot. The moment that more choices were offered, the whole thing fell apart. The second we were able to, we left our simple pre-modern rural community and moved to the city, where scarcity of options is very much not the problem.

What we have today is a nationally and globally integrated system of media in all formats, mixing synchronous and asynchronous in both traditional ways (watching a live stream on a television set, reading an online publication) and novel ways (a livestream embedded in a social media post with commentary in text, or a recorded video within a frequently updated breaking-news page in an online publication). And while non-news alternatives drove the decline of TV news audiences, it has not meant the complete death of news. According to one recent Pew survey, 86 percent of US adults get at least some news online (meaning a huge supermajority is getting some news from somewhere). The comparable figure for TV news was 64 percent, close to two-thirds. Americans are still getting news (with at least 57 percent getting it “Often”), they are just getting it from a huge variety of places. As Will Stancil recently put it, it is not so much that we live in information bubbles today as that we are offered an enormous information buffet, from which we all choose different (if overlapping) combinations of dishes.

That overlap may be larger than he thinks—for openness does not imply an egalitarian outcome. Network science is quite clear that popularity follows a rich-get-richer dynamic, in which getting some attention increases your odds for getting yet more attention, and for a subset of people and organizations this cascades until that subset commands the lion’s share of attention. In pure percentage terms, this results in concentration even greater than the Big Three Networks, with something like 1 percent of content creators getting 99 percent of total views.

Of course, 1 percent of content creators today is rather more than three TV networks showing one show each at any given moment. Given the mind-bogglingly large distribution of attention—with influencers producing for audiences of hundreds of thousands in the middle region and an expansively long tail beyond them—I would not even know where to begin quantifying the absolute number contained within the top 1 percent. It is large. Even if cable TV offered a thousand channels, it would not come close to the total number of “channels” in the top 1 percent of attention in today’s public sphere overall.

Just as attention is concentrated on the top 1 percent of content producers, so too is it concentrated on the top 1 percent of topics. It is often said these days that we are living in alternate realities from one another. It would be more accurate to say we stare at the same reality and yet see completely different things. From 2017 to 2021, absolutely enormous audiences all paid attention to Trump, to COVID, to, on that fateful day in January, the insurrection in the Capitol.

One result of the concentration of attention not just nationally, but globally, is a perverse fixation on niche American intraelite controversies with an illiberal bent. For example, a cross-partisan elite consensus among the British appears fixated on producing anti-trans articles and policies even though two-thirds of the British public have said they pay very little attention to the issue. When world dictators are talking about “cancel culture,” something has gone terribly amiss in the allocation of people’s attention and interest. When the third wave of democratization began winding down, liberals around the world should have been focusing on consolidating our gains in places where egalitarian ideals had not yet sufficiently displaced traditional ones rooted in social hierarchy. Instead, our media environment globalized the American culture wars, to everyone’s detriment.

If the Big Three era provided Americans with a single mirror which reflected the world and themselves, the globalized era of the “information buffet” has shattered that mirror into a thousand pieces. We are still looking at the same reality, and indeed more people are looking at the same things than ever before, but each from a different combination of shards we choose to check, reflecting different angles with their own particular distortions.

The result is a dizzying array of communities of reflective beliefs, some very small, some very large, some very local, some very global, with everything in between. Our party system being what it is, these things are to some extent polarized into two broad opposing camps, but around each pole are countless semi-overlapping subcommunities, with their own talking points and version of events. Large communities quickly become beset with controversy because their members bring with them conflicting reflective beliefs from a variety of other communities. Outside of one to one communication and small group chats, there is very little peace to be found in our raucous, fractured public sphere.

Authority and insurgency

The things that were good about the Big Three were indeed, very good. But it’s easy to assume that this was the result of something intrinsic in the media system rather than contingent in the politics of the era.

Big, concentrated broadcast-based systems by their nature are biased towards the big institutions of society that sustain them, while small actors aiming to make it big from within our wide-open Internet-enabled public sphere are going to be biased towards anti-institutionalist rhetoric. The former benefits from the status quo, while the latter is trying to change it in at least one way, by getting a seat at the table themselves.

The small-c conservatism of the Big Three era seems appealing for the entirely contingent reason that what they were conserving were the institutions and politics that the New Deal made. If America had succumbed to the tide of fascism in the ‘30s, who knows just what sort of conventions the Big Three might have conserved?

The nihilism of the social media era, by contrast, seems unappealing in no small part because it has, in America specifically, helped conservatives more than others, conservatives who have for decades defined themselves as insurgents against a hegemonic New Deal liberalism, and ultimately against the institutions of liberal democracy that made the New Deal possible in the first place.

Things look differently when you are organizing an opposition to a genuinely authoritarian regime. And unfortunate as it may be, that is exactly what we now must do. When what you are trying to do is stop the federal government from acting at all costs, the negative bent of our current media environment is a boon, not a defect. Just as millions could turn out to say they were against what happened to George Floyd, but agreeing on particular solutions was trickier, so too is the necessity of mobilizing against the Trump administration a relatively easy task. Especially when they have taken less than two months to send the booming economy they inherited into a contraction.

But the conservative movement is a cautionary tale; an insurgent mindset is not enough. While we must focus intensely on short term opposition for now, we must also be prepared for what we will do when we take power again. Just as we need to plan for a Reconstruction of our political system, we need to start thinking about a Reconstruction of the liberal public sphere for the era of media we actually live in.

What should that entail? I don’t have any big, silver bullet answers to that question. But I have a few, very preliminary thoughts to offer, on where to invest your money as someone to who wants to support this effort financially:

- There are two sorts of enterprises you can seek to support: small to medium sized outlets that have an audience of influential people, and newcomers that you believe have a potential to grow very large. The former are somewhat easier to identify today and ensure (so long as you believe their influence is good and liberal) that they remain on sound financial footing. The latter is more likely to be hit or miss, and much more often miss. Little more than trial and error is really possible, but the more of us there are out there trying, the more likely we’ll find some that succeed.

- If you have legacy local newspapers that are struggling, please support them. If there are newer local initiatives trying to get off the ground, support those as well. If there is nothing, consider starting something, anything, yourself! Many people prefer to get their news locally but the economics of our moment are brutally unfavorable to that model. If we can get genuinely liberal media doing good work in currently undercovered localities, we stand a good chance to move the politics of those places.

- In general, support publications that publish and pay multiple people over individual Substacks. The most important exception to this is writers who do work that the media industry drastically undervalues. This means actual reporters, not commentators, not pundits, not quant analysts with smart takes, people actually developing relationships with sources and digging through archives and other thankless work that takes tons of time that hardly anyone pays for and too few pay attention to. If you find individuals like this, like Marisa Kabas or Radley Balko, absolutely do become a subscriber at the highest tier you feel comfortable with.

- Much as it pains me to say this as a writer and publisher of written words, you should prioritize outlets that have a demonstrated ability to garner large audiences for live video, or live audio.

- In all cases, find those that are actively doing their part as genuine opposition media today, but also offer a positive, liberal vision for a future after Trump. And very critically: they are grounded in reality, have high standards of evidence, and genuinely think the Scientific Revolution and modern medicine were positive developments and we ought to do more of that kind of thing.

A proposal that is often advanced in these discussions is to, once Democrats are back in power, create a BBC-like national news organization. We’ve discussed the dangers associated with such things, though those dangers are mitigated by the fractured reality of our current media system. Of course, that very mitigating circumstance also reduces the potential benefits of such an arrangement—it’s not as though the existence of BBC has precluded the last decade of clownish and self-defeating politics in the UK. This could also be pursued at the state level, either unilaterally or through federal grants—though while this would make it less likely to have one national one that goes bad, it does increase the odds of red states mucking with it.

A great deal of work needs to be done, and details to be fleshed out. But we absolutely can build a large, influential media bloc that not only opposes fascism today, but can form a critical pillar of a renewed liberal democracy after we have chased the fascists out.

Books cited

Anderson, Benedict. 2016. Imagined Communities. London, England: Verso Books.

Singh, Naunihal. 2014. Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Featured image is Walter Cronkite - covering Apollo Moon Landing1969, Polaroid off TV, by Charles Kremenak