A Liberal Alternative to Realist Errors on Ukraine

American theorist John Mearsheimer has been making the rounds claiming that the West bears the majority of the responsibility (this month in The Economist) or fault (in 2014 in Foreign Affairs) for the war in Ukraine. It is perhaps odd for a proponent of a Realist international relations theory—which claims to deal only with what is, not what ought to be—to be dealing in questions of blame, but Mearsheimer has managed to gain quite a bit of publicity, and more than a few admirers, for taking this position. The root of his claim, which he made about the 2014 crisis as well as the present one, is that America-driven NATO expansion into the former Soviet Bloc made war inevitable, which American foreign policy makers were too idealistic to realize. His writing, however, ignores his own previous assessment of the European security situation, and his recommendations would lead to—by the prediction of his own framework—a broad swath of insecurity running through the middle of Europe. Counterfactuals are fraught, but Mearsheimer has already used them to assign blame for the war in Ukraine on the West, and so it’s worth scrutinizing his claims on his own terms.

A question of hegemony and security structures

Mearsheimer, like most realist theorists, holds that the world security situation is essentially anarchic and thus that states fundamentally must always be trying to maximize their own power to ensure that they can protect their sovereignty from other states. Particularly important in Mearsheimer’s worldview, however, are hegemonic or potentially hegemonic states—those political units with the capacity to extend their power to their entire region, overawing any potential rivals with both their actual might (based on current military power) and potential strength (based on their population and economy).

Regions thus can be described in terms of the relationships between great powers—are there multiple countries with the potential to dominate others, just two, or only one? In his seminal work The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, Mearsheimer argues that the most dangerous kind of power structure is ‘unbalanced multipolarity’—a multipolar system where one country has the potential to seize control of the whole system. In his understanding, the post-WWII situation in Europe has been somewhat unique—first, in that the system was polarized between two major powers (the US and USSR), and then that the US served the position as an offshore pacifier. Mearsheimer believes that this US role is not inevitable, and indeed he wrote in 2001 that it seems to be coming to an end, arguing that “America’s Cold War allies have started to act less like dependents of the US and more like sovereign states because they fear that the offshore balancer…might prove unreliable”.

The situation of Ukraine

Mearsheimer holds that, in a realist framework, Russia has no choice but to control Ukraine if it wants to protect its own security. His argument is that the 2008 decision to consider Ukraine and Georgia for membership—though without extending a formal candidacy—pushed Russia over the edge. Unable to accept NATO members on their borders (beyond the borders already present around its Kaliningrad enclave and short border with Estonia), Russia started to take action, first invading Georgia over disputed territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and then reacting to the 2014 unseating of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych by annexing Crimea and supporting separatist movements Eastern Ukraine. This all, Mearsheimer assures us, was an inevitable result of NATO expansion up to Russia’s borders, and a statement of Russia’s non-negotiable security interests.

To defend this position, he turns to history. In 2014, writing for Foreign Affairs, Mearsheimer describes Ukraine as “A huge expanse of flat land that Napoleonic France, imperial Germany, and Nazi Germany all crossed to strike at Russia itself…a buffer state of enormous strategic importance to Russia”. The history is a bit idealized, however, and in some details it is simply wrong. Napoleon marched through Poland, Lithuania, and on to Moscow—never entering Ukraine. Imperial Germany never reached Russia by means of Ukraine, instead fighting along a long front stretching from Latvia to Ukraine. Even Hitler, who did conquer Ukraine in its entirety, sent his forces through an entirely separate route through Poland and Belarus to Moscow, with secondary pushes through the Baltics to Petrograd and through Ukraine to Stalingrad.

This is not simply a matter of historical pedantry. Rather, the unique position in which Mearsheimer’s 2014 account seems to place Ukraine in fact applies equally well to Poland and the Baltic states—perhaps better, given that Estonia is a short drive from St Petersburg, Russia’s second city, and the Baltics essentially surround an important Russian base in Kaliningrad. Russia’s security concerns did not simply apply to Ukraine and Georgia, but rather to all of the Warsaw Pact. If that’s the case, then if the fight now was not over Ukraine, it would have been over Poland or Estonia instead (and if we take Mearsheimer’s point, that Russia needs to secure the land routes to its core at any cost, such a conflict is inevitable in the future if Russia gains the capacity to do so).

An alternate reality

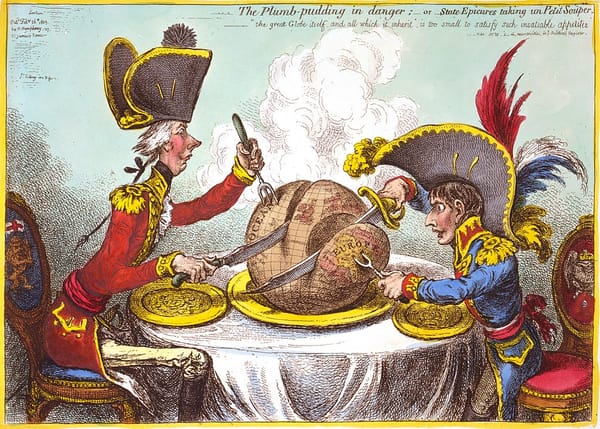

Thus, to work around Russia’s feelings, NATO would have had to forgo any of its efforts to expand into Central or Eastern Europe, or perhaps disband entirely. This would certainly mean a diminution of American investment in European affairs, leaving a broad swath of land from Bulgaria to Estonia unaligned. Mearsheimer provides us with as useful a prediction of what such a world might look like as any.

Mearsheimer blames ‘liberal’ international theory for the conflict in Ukraine, and so the idea that economic interconnectedness and norm-setting institutions could put an end to greater power struggles—the dream of the European Union—is nowhere to be found in Mearsheimer’s account. Rather, he sees a continuing pattern of great power conflict, and identifies Germany as the most likely potential hegemon. With its population of 80 million and strong manufacturing economy, Germany of course seemed like the most plausible candidate for a potential hegemon—against which other European powers would have to balance.

There is another possibility, however. In 2001, it was unclear what direction Russia’s economy would go. But with its larger population and massive nuclear weapons arsenal, Russia was certainly a contender for regional hegemony if its economy was able to recover. Today, however, when adjusted for purchasing power parity, Russia’s GDP has topped four trillion dollars—comparable to that of Germany. Factoring in Russia’s nuclear arsenal and the handicaps imposed on Germany’s military power, Russia—in a NATO-less world ruled by the principles of realism—was a natural rival to Germany.

There is evidence that Russia already anticipated this and sought to shore up its position in former Soviet states even before NATO expansion was offered to Georgia. Russia had troops in Transnistria (in Moldova) and Abkhazia (in Georgia) serving as peacekeepers in the early 1990s. In the mid-1990s, the Collective Security Treaty Organization was founded, establishing mutual defense between Russia, the Central Asian Republics, Armenia, and Belarus. Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova agreed to a balancing coalition for economic development (‘GUAM’). Even before NATO expansion began into former Warsaw Pact states, states had started to form the balancing coalitions, just as realist theory would predict.

Where would that leave the more than 100 million people in countries Mearsheimer would exclude from NATO? The world does not lack for examples of parts of the war caught between potential regional hegemons. The countries of the middle east caught between Iran and Saudi Arabia, or even Russia and Turkey supporting opposite sides of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, provide illustrative examples. This might take some trouble off the shoulders of the US, but it is hardly a rosy picture for the region as a whole.

A fantasy of neutrality

Knowing this is not an attractive scenario—especially compared to the current one, in which most of the former Warsaw Pact members are relatively secure and prosperous members of NATO and the EU—Mearsheimer invents a different one. He argues that Ukraine could be a neutral buffer state, something like Austria or Finland were during the Cold War. Admittedly, this would mean surrendering some of its sovereign rights as a country to join mutual defense pacts, but according to a certain logic this is justice: the weak suffer what they must.

The problem is that this is a fantasy for at least two reasons. The first is that it can’t be limited to Ukraine—as noted, a Russian state with the capacity to do so would no doubt attempt to close off the potential hostile approaches through Poland and the Baltics if we are to take Mearsheimer’s historical analogies seriously. The maintenance of a neutral zone between blocs that is more populous than one of the blocs it seeks to separate (and Poland, Ukraine, the Baltics, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechia have a population roughly equal to that of Russia) is difficult to imagine.

The bigger problem is that Ukraine is not Finland or Austria. These two states had two major advantages in their quest to become neutral zones—they are relatively small and out of the way. With a pre-war population of 40 million, Ukraine is six times larger than Finland and four times larger than Austria. No one expected the Finnish or Austrian armies to be a deciding factor in a Cold War showdown. Ukraine, however, is nearly a third the size of Russia; for either side of a great power rivalry to leave that kind of potential military might ‘on the table’ is nearly unthinkable. Moreover, its location is unenviable for those who would like to live in a neutral state. Switzerland and Austria were able to remain neutral during the Cold War because, even during such a war, it was not likely to be an important battle ground. Finland was able to be neutral because it was far separated from any likely theater of conflict—there was no such thing as Finnish neutrality when Sweden and Russia were rival world powers, or Alpine neutrality when the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor were trying to exert influence across them.

Central European neutrality would never hold up over the long term. It might allow the US public to satisfactorily wash their hands of the fate of the people over whom World War II and the Cold War had ostensibly been fought. No hegemon would emerge, and the US, it’s true, would remain unthreatened (as long as Germany did not develop nuclear weapons to counter Russia, though Mearsheimer predicts they would). But it is very difficult to argue this would be better for the people of Ukraine, or for the national power and honor of the United States.

A more liberal approach

What is the alternative to the kind of ‘hands off’ approach that Mearsheimer proposes? The most influential alternative to this kind of realism in international relations theory is liberalism, which holds that states need not always seek power over one another because institutions, norms, and interconnected trade can restrain violent conflict. It has been fairly accused of having a Panglossian bent. Economic institutions like the European Economic Community and later EU, with their open borders and robust trade connections, may have contributed to ending the cycle of wars in Western Europe but they have been unable to curb conflict between Russia and its neighbors.

In reality peace is a two way street—there is no policy by the US and its allies that can avoid all wars unless other countries cooperate. But there is a very real way in which Russia’s actions are a response to American decision making. The US has both increased the perceived risk for Russia and its allies and fatally weakened the most basic international norms by pursuing a policy of regime change in Iraq and elsewhere. Regime change as policy, whether pursued through military action or a crushing sanctions regime, is anathema to liberalism because it breaks down the base level trust needed for countries to even contemplate cooperation. Biden’s recent statement that Putin ‘cannot remain in power’ is a blunder here that cannot be repeated.

To the limited extent that the US is at fault for creating an international order in which Russia felt threatened enough to take an enormous risk invading Ukraine, and was unconstrained by international norms, it is through the invasion of Iraq and the sanctions regime against Iran. The former tied down an enormous portion of US military assets, and those of our allies, while the latter diluted the power of economic sanctions. And both strategies, as they were transparently focused on regime change, made it difficult to rally a global response to Russia’s invasion of Georgia, which by comparison had a much more modest goal. It was not that an increase in NATO’s geographic size increased the perceived threat towards Russia and made this conflict inevitable. Rather, Russian aggression was made possible because the US squandered whatever liberal credibility it had during the War on Terror. This left liberal institutions weaker and rendered appeals to international law almost laughable.

Accepting that mistakes were made in the past, what is the liberal path forward? For one thing, full throated support of the Zelensky government in Ukraine. Volodymyr Zelensky represents the solid center of Ukraine, avoiding both the outright nationalism of previous Ukrainian presidents and the Pro-Russian tendencies that are likely to be electorally dead for the conceivable future. Most importantly though, he won a resounding electoral victory over two rounds of voting and showed strength in nearly every oblast. For liberalism to triumph in eastern Europe, elected, moderate leaders like Zelensky need to show that they can hold their countries together and usher in prosperity and stability. The US and EU need to make sure that happens.

If the government is preserved, then actual membership in organizations like NATO or the EU is not as necessary. The Ukrainian state, both its armed forces and political apparatus, has proven that it has the resilience and strength to hold up under pressure. The addition of credible third party security guarantees of Ukrainian sovereignty would make a future direct conflict unlikely. More important is that the democratically elected government be given the opportunity to succeed in rebuilding the country. Ideally, this would take place in the context of the EU, but determined assistance from the rest of Europe could have the same effect even without it; if Russia fails to achieve its main goals in the current conflict, a policy of official non-alignment by Ukraine will become much more plausible.

The second shift in policy needs to be to abandon the regime change efforts that have defined US goal making for years. Russia was empowered to invade Ukraine because it had managed to project power in a slew of other regional conflicts, especially in Syria and through its relationship with Iran. As odious as we may find their governing practices, the US cannot afford to make permanent enemies of Iran, Syria, Venezuela, Cuba, Belarus, and, yes, Russia. Sanctions against the first four are unmistakably aimed at regime change but have failed to accomplish that goal. Instead, they have merely driven these states into alliance with Russia and diluted the more acute sanctions levied against Russia and its partner Belarus. Making real change to our sanctions diplomacy is necessary so that when countries commit major breaches in peace, as Russia has done, the sanctions that can be levied are truly exceptional, and are applied only as long as necessary so that it is harder for countries to adapt to them.

Similarly, NATO and other international treaty organizations need to withdraw from the regime change game as well. Even acting under the auspices of the UN Security Council, the use of NATO forces in roles other than strictly mutual defense ones increased the perceived threat of the whole organization. Far more than geographic expansion, it is expansion in mission that has made NATO a perceived threat to other nations.

Can these steps guarantee that there will not be another conflict in the future? No, and any theory that can claim such an outcome is making outsized promises it will not be able to deliver. But liberal theory based on expanding zones of mutual defense and economic cooperation has delivered unprecedented peace to Western and Central Europe. If the leading nations in NATO and the EU, most especially the United States, support the elected Ukrainian government and adopt more consistently liberal principles, there will be a real chance to expand this peace regardless of the precise resolution of the current conflict—and this outcome is surely more attractive than the ostensibly realist alternative of resigning the entire region to a perpetual tug of war in an impossible quest for neutrality.

Featured Image is the World Trade Organization