A Realist Defense of Legislative Supremacy

The triumph of modern representative democracy was, in part, the culmination of a moral revolution. The heralds of this revolution were those great documents of the 18th century, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Today it is a commonplace that the people are sovereign and that self-government is morally superior to autocratic or totalitarian rule.

The moral revolution has obscured a structural revolution and its practical consequences. After all, it is not just that we believe in democracy these days; we have adopted specific institutions and procedures. While it is very poetic to speak of “the will of the people,” it does not tell us much about whether or not that will is better expressed by a directly elected president or by a legislature which divides the population into different districts to represent separately. And if it truly is the will of the people being expressed, why elect representatives at all? Why not vote directly on all laws?

The moral story is incomplete. Representative democracy is a moral achievement, but it is not just a moral achievement. Its great global success does not chiefly rest on its morality but on its realism. Centuries ago, the extremely militant societies of Europe established parliaments for their military and economic powers to peacefully agree upon mutually binding laws. As the age of agriculture gave way to the age of industry and commerce, modern representative institutions developed out of the old ones, better reflecting the broadening distribution of social power.

This practical lens provides more concrete answers to the questions posed above. For example, a single officeholder, such as a directly elected president, can afford to ignore quite a large portion of the population without much risk at the ballot box. That ignored portion of the population collectively hold the power to make a great deal of extra-institutional trouble for a regime if they are unable to find institutional representation for their interests.

A legislature is therefore superior to a single office holder not because it provides a superior expression of “the will of the people,” but because it creates advocates for specific subdivisions of the population. These advocates sit at the center of political power and participate in creating the country’s laws. A legislature ensures that much more of the population has someone who cannot ignore them and hope to stay in office, and therefore none of the broad interests of society will be entirely neglected. At minimum, they can expect their representative to perform constituency services, interceding on their behalf with the executive bureaucracy.

We need to move beyond muddled moral maudlin understandings of representative democracy paired with simple institutional provincialism. We need to better understand its basic structural strengths to better understand which types of reforms are likely to build on these strengths, and which are likely to be counterproductive. We need to meet the authoritarian’s accusations of weakness and ineffectiveness with the confidence representative democracy has plainly earned.

The nature of legitimacy

Legitimacy in the sociological sense is deference to an authority by a group over which that authority is held. We can see this clearly if we focus on a simple case: a court going through bail hearings. The bailiff and the guards defer to the authority of the judge, for they are part of the same organization. Defiance on their part puts their next paycheck in jeopardy; they have a personal stake in having a proper attitude towards the organization’s authority structure. Nevertheless, they can be more or less diligent in their jobs, more or less publicly and privately deferential to the judge. These differences add up, especially when they are collective rather than simply stemming from an individual’s quirks.

The prosecutor and the defense attorney are in a similar situation, but less direct. The judge cannot have them fired from their place of employment, but their roles only have meaning, and therefore value, within the authority structure of the court system. Nor could they individually accomplish much without it; a defiant defense attorney will simply be restrained by the bailiff while their client is taken away. A defiant prosecutor can work with the police to make life difficult for a defendant the court sets free, but their ultimate victory over the defendant depends upon the authority of the court. Nevertheless, the level of deference shown by prosecutors to the authority of the court system matters. A high level of deference among both the lawyers and the court system employees creates a more tightly coordinated institution that is therefore more difficult for outsiders to resist.

Most important for understanding public legitimacy is the gallery, filled with people waiting for their own cases to be heard, perhaps with their family and friends. Their relationship to the proceedings is more ambiguous. They are not, for the most part, employed by some organization that makes up the legal system. They lack familiarity with the specifics of the proceedings and expectations about how these things normally play out. For the most part, this group watches quietly as the judge sets bail and defendants leave to either pay up or be taken into custody. If it all operates relatively smoothly, the people in the gallery may find themselves with a sense that this is how it is supposed to work, a sentiment that encourages the perception of legitimacy beyond the people who have a direct stake in the system.

Let us consider what different levels of legitimacy mean in practice by walking through a few specific scenarios.

Imagine a case where a considerable number of the people in the gallery believe the judge has set bail unfairly high. At high levels of legitimacy, not only will no one interfere, but hardly anyone even imagines the possibility. The judge’s authority seems obvious, to question it seems absurd, even when the exercise of that authority violates the personal sense of fairness or justice of some.

By contrast, imagine now that most of the people in the gallery believe the judge has set an unfairly high bail, and none of them believe he had the right to do this, but none of them has the courage to say or do anything. None of them knows how many others share their point of view, and all know who the bailiff and the guards will side with. The court has the advantage in commanding the organized use of force in this case, and in mutual mistrust undermining the possibility of action from the gallery, on the other. But the situation is clearly much more tenuous than our first one. Under the right conditions, it could turn into a riot.

Consider one final scenario, where the general public all believe that the judges wield power arbitrarily and unjustly, and that they need not be obeyed. In practical terms this would likely mean that courts could not risk allowing very many people in at a time, relative to the number of guards. This would slow down their operation considerably, leaving defendants to languish in jails in the meantime, exacerbating the decline of the court’s legitimacy.

Taken to its logical extreme, the criminal justice system overall may find it difficult to keep prisoners imprisoned or guarantee the safety of anyone on the premises of the court building. Guards and policemen, after all, are all surrounded in their social circles by people who are simply normal members of the public. If legitimacy among this broad group falls far enough, the institution’s own actors may begin to work with the public against it. At that point, an institution truly enters a trajectory of terminal decline.

Underneath the seemingly academic discussion of legitimacy are these very real, very high stakes. Avoiding the last scenario and moving closer to the first are central goals of any regime. It is important to emphasize that, while there are many standard ways to approach these goals, none provide guarantees. Events proceed unpredictably, regardless of plans or intentions on the part of authorities and their most capable subordinates. The dynamic perpetuating the decline may be one inherited by current elites and one that’s difficult for individual actors to break out of alone.

Much will come down to specific contingencies; leaders with the right political sense for their particular time and place being well positioned to take action, how history has shaped the receptiveness of the particular public towards particular institutional options, or whether or not there is a military that is willing to go along with choices made by a civilian government.

It is also important to remember that “the public” is not a singular entity. A regime may obtain legitimacy in the eyes of some groups but not others. Within groups that show a great deal of deference the regime’s authority, there may be individuals who show it very little. The difficulty of securing legitimacy across groups and across many individual differences should not be underestimated.

Caveats aside, representative democracy has clear advantages in the field of legitimation. The early European parliamentarism from which modern representative democracy springs owes its origin precisely to the need for regimes to obtain legitimacy in the eyes of those with the power to make trouble for them.

Parliaments and legitimation

While councils were common among pre-modern monarchies around the world, the special weakness of medieval European monarchs forced them to rely on these bodies not just for advice, but as a means to draw the support of those who held independent bases of power. A king would gather “his lay and clerical vassals” to ask for “a one-off subsidy.”

Often such a request for a subsidy was made in an assembly to which the sovereign summoned his noble and clerical vassals in order to discuss, negotiate, and agree on the requested sum.[1]

Over time this arrangement became institutionalized: “What distinguishes a parliament from a council or an ad hoc assembly is that it forms an independent body, a legal and political entity, with certain rights and obligations, which guarantees the continuity of its activities.”[2]

These early parliaments were not merely forums in which kings asked for the support from their vassals. They also became assemblies in which laws were made, which kings then committed to uphold and—crucially—to hold themselves to. The strength of this arrangement is that it brought all the great powers of a domain together and provided a peaceful procedure by which they could influence the law and governance of the realm. Even if some nobles found themselves in the minority on a particular question, it would be far less risky to attempt to build up their coalition in parliament than to resist by military means. There was therefore value for the de facto powers of the realm to preserve parliament even when any given noble may not agree with any given decision reached there.

In short, parliamentary procedure served as a powerful tool of legitimation, contributing to the stability of the realm and providing a means for kings to seek material support, but at the price of the king and the participants binding themselves to the outcome of those procedures. It is important not to mistake this for the power of formalism per se. The power of this arrangement lies precisely in its ability to facilitate coordination among a group of people in society who collectively command more power—economic or military or both—than the king. In England, the conflict between a set of barons and a weak king resulted in the Magna Carta, as the barons forced the king to agree to formal restrictions on the authority of the crown to avert open conflict. They did this not because they had a better legal theory than the king, but because they had superior strength, and demanded lawful behavior as part of the terms of their renewed loyalty.

Predictably, when kings consolidated their power, the use of parliaments declined. And when kings were at their weakest, they convened parliaments quite frequently. In Spain in 1188, after the conquest of several cities, King Alphonso IX convened a “Cortes” in Leon with an important innovation: it assembled not only clergy and nobility, but “the elected citizens of each city.”

In order to avoid alienating the new citizens, these captured cities were turned into independent towns—communes—with royal consent, instead of being given in fief to some lord who had helped with the military campaign.[3]

The tenuousness of the situation in post-Reconquista Spain strengthened the position not only of nobles and clergy relative to the king, but of certain classes of commoners relative to all of the above. This was not peculiar to Spain but occurred throughout Europe. There was a “communal movement of the eleventh and thirteenth centuries” in which “self-governing” cities became “corporate bodies with rights and privileges.” The inclusion of representatives from these cities made parliaments much more recognizably like their modern descendants.

From a gathering of peers it developed into a (more or less) formal meeting of representatives of different estates, which often (. . .) changed the modus operandi of the institution fundamentally.[4]

Herein lies the root of modern parliamentarism, and therefore of modern representative democracy: the merchant class grew in political and economic strength because the regimes of medieval Europe were too weak to stop it from happening. Once it happened, those merchants were able to institutionalize their gains through representation in parliaments. This was not the end of the story; the peculiar conditions of the European middle ages lasted for many centuries but not forever. More and more kings successfully centralized power and authority, at the expense of the “estates” in general and of parliaments in particular.

But this did not occur uniformly across all of Europe. In the English Civil War, the powers represented by Parliament showed themselves to be strong enough together to militarily defeat the king. This strength could later be bartered, in what was called the Glorious Revolution, to legitimate the rule of an invading power. The concessions Parliament received secured its centrality in England and planted the seeds for modern representative democracy. After 1688 Parliament met regularly and it was established that “kings could not legislate, govern, raise money, or maintain an army without Parliament[.]”[5]

The turn to representative democracy

The great practical merit of representative democracy continues to be in the function it shares with the early European parliaments. Legislatures are a gathering place for representatives of the various interests and powers of society to agree upon and legitimate mutually binding laws. What changed is that societies became increasingly literate, commercial, and urban, which necessitated establishing the regime’s legitimacy as widely among the population as possible. Representative democracy provides by far the best tools to pull this off.

Great Britain’s constitutional monarchy, as well as France’s more halting and complicated experience of republican parliamentarism, provided models that soon spread throughout Europe and the world. An important part of this really was a moral revolution; the great political documents of the 18th century signaled a radical shift in the nature of legitimation. Legitimation rituals and narratives in pre-modern societies were framed from the top down, the top being either the king or God.

But the early champions of representative democracy began to change all that by demanding that legitimacy be granted from the bottom up. Specific theories about the sovereignty of the people, the social contract, and expressing the “will of the people,” among others, began to gain respectability among elites in Europe and their colonies, something that became more pronounced in the 19th century.

This shift represents a real victory of moral persuasion. But the success of these ideas in implementation rested on the increased power that ordinary citizens began to experience as a result of modern economic growth. Populations concentrated in cities can become collectively threatening much more quickly than populations dispersed across the countryside. The cumulative resources available to the masses and especially the large emergent middle classes created vastly more potential power than the medieval merchants ever amassed, shared very broadly. It is difficult to believe that representative democracy would have found as sure a footing as it has if ordinary citizens had not collectively become potentially so dangerous.

Putting legislatures at the top of the legal hierarchy is both more pragmatic and more moral than alternative approaches. This is why constitutionalism should be understood as a qualified legislative supremacy. Here in the United States, though our amendment process is impractically supermajoritarian, it is undeniably legislative in nature; it requires 38 state legislative majorities to join congressional supermajorities.

Political parties

One vision of what representative democracy ought to look like in the American political tradition emphasizes the duty of ordinary citizens to contribute to the work of governing. Within this tradition, the idea of a professional politician is anathema, and professional parties are viewed as simply vehicles of corruption. We see the reach of this tradition in, for example, the minimal budgets allotted for state legislators’ salaries and staff.

This vision runs up against basic realities of modern government and the empirical experience of representative democracy. Representative democracies produce professional politicians: this is a fact. No reform in any representative democracy in the world has successfully avoided this outcome. When low salaries make it impossible to earn a living as a legislator, the retired and the independently wealthy have dominated the job. When sufficient staff are not provided, legislators have turned to well financed interest groups for support. Hardly desirable outcomes!

We would not want just anyone to represent us in court, and we should not want just anyone to represent us in the legislative process. The history of ballot initiatives and other “direct democracy” measures is checkered at best because the typical voter simply does not know the details of law or policy well enough. Interested groups can game the process much more effectively than ordinary voters.

But professional legislators supported by professional staff are better able to command legal and policy details. And the way that these professionals organize themselves for action is through political parties.

Though political theorists neglect and scorn them by turns, parties serve critical functions in representative democracies. They structure the potentially messy confusion of elections into a “regulated rivalry”[6] between the governing party on the one hand and the opposition on the other. By formalizing which faction has control of the legislature and which is out of power, the stakes of elections become more clearly defined, and coordination is facilitated among candidates to build the overall electoral coalition that might keep them in power, or bring them into it. In defeat, the opposition is forever seeking to make the case for power to change hands, making it difficult for the governing party to rest on its laurels.

A party is “an organized group capable of assuming office and authority and willing to do so[.]” They are “organizations for selecting and training political leaders”[7] and in so doing build up a political class with the capacity to govern.

Parties are also an important buttress against capture by narrow interest groups. When parties are weak, interest groups play a stronger role in governance by finding individual politicians to become a backer of. Party discipline allows the party to collectively negotiate the best overall deal in terms of mutual support across a coalition of interests, lowering the risk of defection on the part of individual politicians.[8]

Finally, with the exception of chief executives such as presidents, governors, or mayors, most voters do not really vote for candidates. They vote for (or against) parties, on the basis of their perception of that party on the whole. The party “brand” serves to economize the amount of information a voter must know in order to make a decision. Infamously few American voters know who their senators are, much less their representative, and heaven help us when we get to the state level and below. Not knowing the people, they will vote according to which party the people are members of. Anti-party reforms which attempt to make systems more candidate-centric simply ignore this basic fact of how real world voters behave.

In short, parties provide a structure for the “regulated rivalry” of peaceful democratic competition, they develop the capacity to govern even when out of power, they manage interest groups better than individual politicians could, and they allow voters to economize on information. These are their basic functions.

The ideal representative institutions ought to be exclusively legislative, involve a truly competitive multiparty system in which the votes of a group comprising even 5-10 percent of the population can make a difference under the right conditions, yet still enable the governing coalition to regularly pass legislation that successfully molds the character of the political and legal systems.

Pain points

Party led representative democracy encompasses a wide range of potential institutional forms. Some work better in general than others, some are better for particular types of societies, and all have weaknesses and fall short of the idea described above. The key thing is the interaction between the formal system with the structure of the underlying society.

The Israeli party system, for example, is quite unstable. This is partly because of their unicameral party list system, which promotes a plethora of very small parties even after they raised the threshold for obtaining seats. though much of the troubles in institutional design rest at a level of detail quite a bit more granular than that high level description implies.[9] Consider an abbreviated list of their 120-seat legislature’s party composition from in 2020:

| Party | Seats |

| Likud | 36 |

| Blue and White | 33 |

| Joint List | 15 |

| Shas | 9 |

| UTJ | 7 |

| Emet | 7 |

| Yisrael Beiteinu | 7 |

| Yamina | 6 |

The Joint List is a party representing the interest of Arab Israelis. Given that the largest two parties were rivals for heads of a coalition, the Joint List’s 15 seats were quite substantial. Joining with them would significantly reduce the number of other parties the coalition leader would need to cobble together to get to 61. But Israeli politics makes it exceedingly difficult to form a coalition with an Arab party. The most recent coalition, formed purely to ouster Prime Minister Netanyahu (who for all the talk of Israeli political instability had held the office for 12 years), was the first one to include any Arab party—the much smaller United Arab List. This was a particularly tenuous coalition that is already on its way out.

The Israeli system makes control of the legislature very difficult to maintain for a deeply divided society. But the divisions in the legislature do reflect real division in the society. Different approaches might merely make it easier to steamroll the Arab Israeli interests, whereas the current arrangement has allowed Arab parties to exercise strategic influence at crucial moments. The country would likely be better off emulating Canada’s approach with Quebec and giving Arab Israelis a great deal more local autonomy. That only works if there is enough geographic concentration, of course; in the Arab Israeli case there just so happens to be.

In the meantime, there is something to be said for making the electorate feel the pain of stubbornly refusing to find some compromise or long term accommodation with major segments of their society. Ethnic and religious pluralism, and really any pluralism worth the name, makes it a challenge to find a single approach that maintains legitimacy across all or most groups. Disempowering Arab Israelis any more than they already have been is a recipe for declining legitimacy with them and therefore greater social unrest. But even the best possible arrangement for a given society will leave some groups with less influence and power than others—this is an unfortunate reality. In Quebec, indigenous people are not necessarily made better off by the French Canadians’ greater autonomy from the national government.

No matter how responsive the legislature is, there will always be some factions or parties that hold less political power than others, and this is unlikely to be purely a matter of their respective proportions of the population. Some, like the Arab Israelis, will struggle to find a place among the major coalitions. Others will face such a large asymmetry in which party better represents their interests that that party can more or less take them for granted, effectively becoming less responsive to their faction. There are many approaches to addressing this but no silver bullet solution.

The Quebec model frees up the national government’s legislature by taking a class of explosive questions out of its hands, at least as far as some particular federal unit is concerned. This works if the group being catered to is sufficiently concentrated geographically, but does little for the group’s diaspora across the rest of the country. Federalism as a general proposition attempts to leave some matters to smaller units than the national government in order to accommodate greater pluralism, but ultimately substitutes the possibility of dominance at one level with the possibility of dominance at another. Each approach can be balanced such that particular groups are well represented on some matter on at least one level or government, but that is far from guaranteed.

And of course, responsiveness is only one quality that legislatures need to have. They must balance this against the ability to take decisive action. Single seat plurality legislatures, often called “first past the post,” make it very likely that a single party will gain a majority of seats in the legislature even if no party received a majority of the votes. This prioritizes stable control of government over responsiveness. Advocates of this system claim it is superior at producing energetic action from the elected branch of government than proportional representation systems are. But the boasted short term stability can come at the price of greater swings in policies pursued for relatively small changes in voting behavior.

One-party cabinets tend to be more durable than coalition cabinets, but a change from a one-party cabinet to another is a wholesale partisan turnover, whereas a change from one coalition cabinet to another usually entails only a piecemeal change in the party composition of the cabinet.[10]

We can see how this has played out in America’s two party system, especially at the state level. When one party sweeps into office they enact drastic changes in the policies there. When their rival returns to power they reverse much of it. Small differences in votes obtained should not translate into such dramatic differences in policy outcomes. A system that’s more responsive overall to voters may see many specific coalition combinations rise and fall in a short period, yet have a relatively stable character overall when compared to the reversals of two-party polarization.

No representative institutions are perfect in either their empowerment of the broad segments of society or in the effectiveness of their actions. But the practicality at the parliamentary core of these institutions is such that even dictatorships often attempt to engage in some form of it, which though severely restricted are not as purely symbolic and outside observers tend to believe.[11]

Democracy and social power

If there is one takeaway for those worried on behalf of the groups that remain the most disempowered in a given representative democracy, it is to focus on the practical details of social power over abstract philosophical reasoning. Consider, for example, the success of a specific policy: the modern social safety net. Its origins lie as much in a desire to preserve public order on the part of arch-conservatives such as Otto von Bismarck as in a moral imperative to provide for the poor. In an urbanized and commercial society, the ups and downs of the labor market hold tremendous potential to create social unrest. One knock-on effect of creating a social safety net to reduce the risk of such unrest, however, is to set an effective floor on the economic power available to the ordinary citizen.

Point being, often the idea of a Quebec solution, or electoral quotas, is putting the cart before the horse. In order to effectively empower a group in the halls of formal representative institutions, you need to first empower that group on the ground. The social safety net helped to institutionalize the growing power of the urban working class. Organizations such as the SCLC mobilized direct action to flex the economic and social muscle of the disenfranchised and segregated African Americans of the Jim Crow South in a way that was impossible to ignore.

Here in America, we often get the worst of both worlds in terms of responsiveness and effective action. There is a great deal of low hanging fruit to be found in simply moving closer to the best institutional designs found elsewhere. We should do so, not just because it is right—which it is—but because it is practical. No small part of our current unrest can be located in the fact that many groups already have some level of power to make trouble for local and national regimes, but the outlets for their peaceful political expression are poorly designed. The moral lens is insufficient to navigate this crisis; a firmer understanding of the practical power of representative democracy provides a better guide for a path forward.

[1] VAN ZANDEN, JAN LUITEN, ELTJO BURINGH, and MAARTEN BOSKER. “The Rise and Decline of European Parliaments, 1188—1789.” The Economic History Review 65, no. 3 (2012): 837. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23271553.

[2] Ibid, 837.

[3] Ibid, 838.

[4] Ibid, 847.

[5] William Selinger, Parliamentarism from Burke to Weber (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 20.

[6] The phrase is from the discussion of Burke’s theory of parties in Nancy L. Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 119-126.

[7] Ibid, 128.

[8] James W. Ceaser, “Political Parties—Declining, Stabilizing, or Resurging?,” in The New American Political System, ed. Anthony Stephen King (Washington: The Aei Press, 1990), 122-123.

[9] A useful exploration of the level of detail that can make a significant difference is found in Michael Laver and Norman Schofield, Multiparty Government: The Politics of Coalition in Europe ; with a New Preface (Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan Press, 2001).

[10] Arend Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012). Kindle Edition. Location 1717-1727.

[11] Xavier Márquez, Non-Democratic Politics: Authoritarianism, Dictatorship, and Democratization (New York, NY: Red Globe Press, 2017).

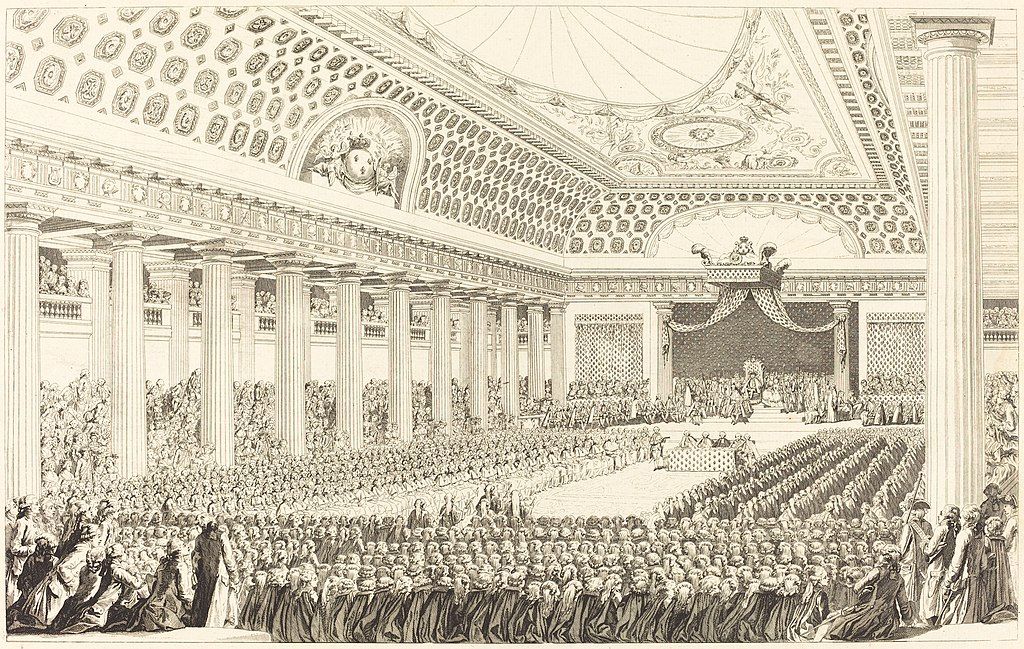

Featured Image is The Opening of the Estates-General at Versailles, by Antoine-Jean Duclos after Charles Monnet