Antisemitism and Intent

“Antisemitism, like racism…requires intent,” Ben Shapiro declared. Shapiro was defending his decision to hire actor Gina Carano to a movie deal, despite the fact that she had shared an ugly antisemitic meme on social media. The meme showed old men with piles of money conspiring to control the globe; it’s clearly inspired by the notorious antisemitic tract The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Bari Weiss acknowledged the meme’s likely origin, but nonetheless agreed with Shapiro. She interviewed Carano, who insisted she didn’t know the meme was antisemitic. As a result, Weiss declared that Carano could not be accused of antisemitism.

Shapiro hired Carano, who had been appearing in the Star Wars series The Mandalorian, after her contract was not renewed by Disney. The ins and outs of the controversy around Carano have been covered ably elsewhere, and I don’t want to rehash that. I do think it’s worth discussing the idea that bigotry depends on intent, though. In this view, a person cannot be antisemitic unless they say something like, “I am antisemitic” or “I hate Jewish people.” This seems clear and fair, on the surface. But unfortunately, to frame antisemitism in this way is a huge boon to antisemites. It allows them to organize and recruit with impunity. It also allows them to target Jewish people for further bigotry and violence.

The first problem with using intent to determine antisemitism is that antisemites often lie. Antisemitism and other forms of bigotry are widely regarded as immoral and wrong. Few people will openly admit to prejudice against Jews. Neo-Nazi Richard Spencer, for example, insisted that he was merely working for white people’s rights. Leaked audio eventually revealed him using racist and antisemitic slurs in private. But should we have taken his claims to innocent intentions at face value before those recordings were available? How can you rely on intent when even the worst antisemites take pains to conceal their beliefs?

Spencer and many others avoid explicit statements of intent through dogwhistles. A dogwhistle is a bigoted statement which is meant to appeal to other bigots while providing deniability. Spencer’s platform of “white rights” is one example. So is the use of terms like “globalist” or even “New York elites.”

Dogwhistles allow antisemites to organize and coordinate in the open, without having to take responsibility for their ideas or beliefs. Dogwhistles can be a signal to like-minded people to send death threats to a particular target, or to swarm them on social media. Politicians use dogwhistles to tell their voters that they share their hatreds and prejudices‚ as in George H. W. Bush’s infamous Willie Horton ad. That ad did not say, “George Bush hates Black people.” Instead it conflated criminals and Black people, and suggested that Dukakis was too soft on both.

Dogwhistles aren’t just intended to alert the faithful, though. They’re also a way to recruit. Clever memes, or certain kinds of populist rhetoric, can appeal to people who aren’t necessarily consciously committed to a program of bigotry or antisemitism. For example, one of my friends from high school shared a conspiracy theory on Facebook about billionaire George Soros undermining democracy. Soros is one of the main targets of antisemitism globally; he is now what the Rothschild used to be. Conspiracy theories alleging that Soros was funding immigration led directly to the 2018 antisemitic massacre in Pittsburgh, where a radical right shooter murdered thirteen people.

My friend didn’t know that conspiracy theories about Soros have been used to organize hate and violence, though. He had just heard a lot about this billionaire Soros, and he distrusted billionaires.

My friend was horrified when I told him this was an antisemitic conspiracy theory; he apologized and vowed to be more careful in future. But that’s not always what happens when Jewish people point out that someone is sharing antisemitism unintentionally. Carano says she was asked to take down the antisemitic meme. She thought about doing so, but then decided she didn’t want to give her critics the satisfaction.

Weiss is sympathetic to this response. “I understand why Carano feels torn about taking down the image: there’s no winning. Leave it up and you’re bad. Take it down and you’re bad, since it’s an admission of guilt.” This frames the issue around Carano’s guilt or innocence, and around her victory and validation. Left out of the discussion is what happens when Jewish people objecting to fairly obvious antisemitism are assumed to be speaking in bad faith.

At this point, Carano knows the image is antisemitic; she’s choosing to leave it up. Rather than being accountable to Jewish people, she’s decided she wants to stay in community with those who share that meme—many of whom absolutely know it’s antisemitic. And in fact, this is why ambiguous images are shared: to lure people in, get them invested in particular images and ideas, and then force them to take a side with their cool, meme-sharing friends, or with those (mean, oversensitive) Jewish people.

This is why discussions about bigotry should not focus primarily on the internal feelings or morality or intent of the bigot. Philosopher Kate Manne has argued that a misogynist statement is not misogynist because the person who makes the statement hates women. It is misogynist because of its effect on women. Similarly, Carano’s intent in sharing the meme has little to do with whether the meme is antisemitic. The question is, what does the meme do in the culture? What effect does it have on Jewish people? That’s not a hard question to answer; the meme denigrates Jews, and it encourages people to associate wealth, power, and secret control with Jews. The meme helps antisemites build power. It’s antisemitic.

Weiss and Shapiro are themselves widely criticized by the left. It’s not surprising that they rushed to show solidarity with Carano when she was also criticized by the left. In taking her side, they argue that they are fighting for free speech.

But in their eagerness to acquit Carano, Weiss and Shapiro have moved beyond defending her right to speak. They’re arguing that antisemitic speech is innocent, and that people who choose to share antisemitic speech and who double down when confronted should be held blameless unless they say, specifically, “I hate Jewish people” or the equivalent. When leading Jewish figures on the right endorse or whitewash antisemitic speech in this way, they are working to weaponize antisemitism against Jewish people, on the left and elsewhere. From now on, whenever that meme is used, Weiss and Shapiro will be cited—by good-faith and bad-faith actors—as a way to delegitimize Jewish people who object and in order to solidify and expand communities who want to use antisemitic dogwhistles. That’s very dangerous, whether Weiss and Shapiro intend it to be or not.

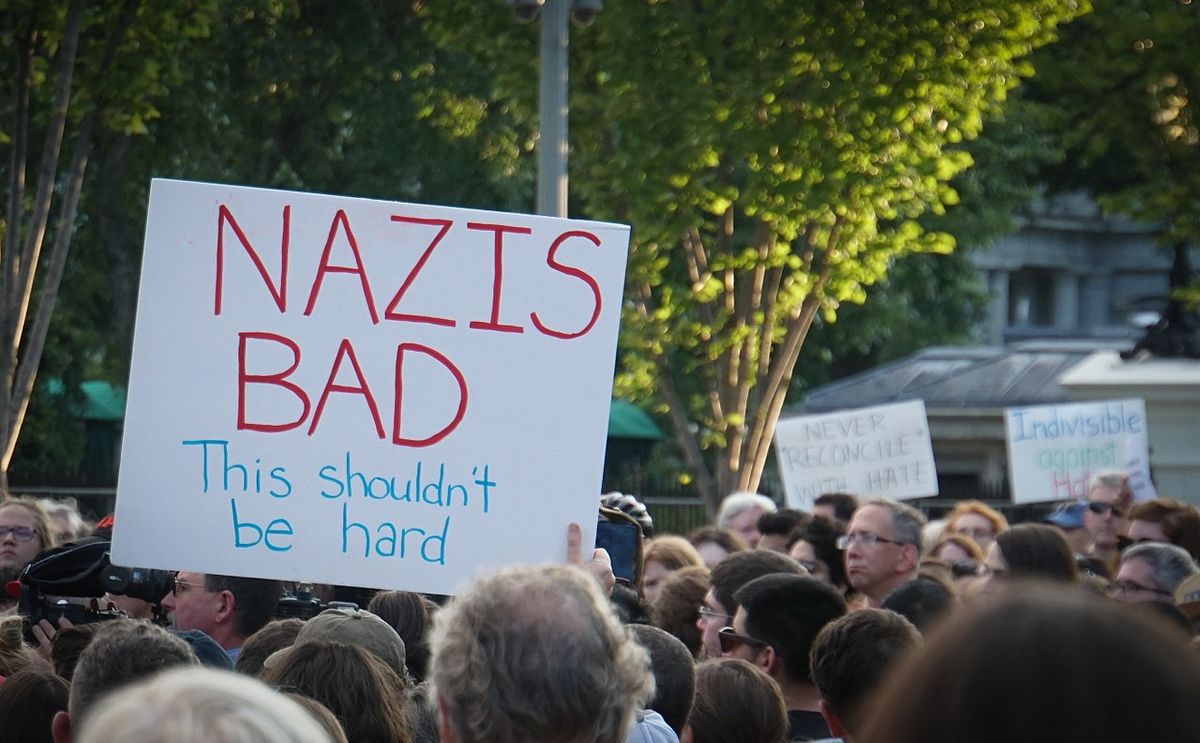

Featured Image is Charlottesville Candlelight Vigil at the White House, by Ted Eytan