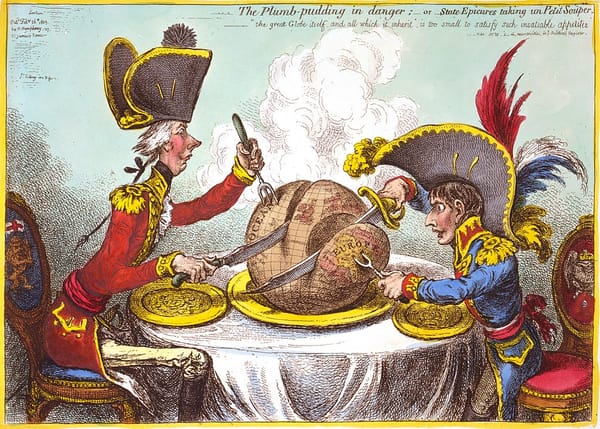

Conservative Cancel Culture After 9/11

“Probably the only thing that genuinely was cancelled in the last 20 years was … The Dixie Chicks,” the longtime progressive blogger Atrios tweeted on June 20. As his use of “genuinely” suggests, Atrios, like many left-wing commentators, is dismissive of the recent flare-up of complaints about “cancel culture,” and when, a couple weeks after this tweet, Harper’s published the now-infamous letter signed by over 150 writers and academics advocating for a culture of free expression, Atrios and like-minded thinkers were contemptuous of it. Critical responses to the letter have been many and varied: Atrios and others have tended to portray the signatories as out of touch and self-interested (“‘I no longer earn $10 per word as I did in 1994, and I blame cancel culture,’” read one tweet) and as pointlessly provocative, even bigoted (“‘Why can THEY say the N word and WE can’t’ an open letter in Harpers,” read another). The typical signer of the letter, according to these left-wing commentators, is secure in their wealth and career and has no genuine cause for complaint, only a peevish distaste for criticism from those who they see as their social lessers.

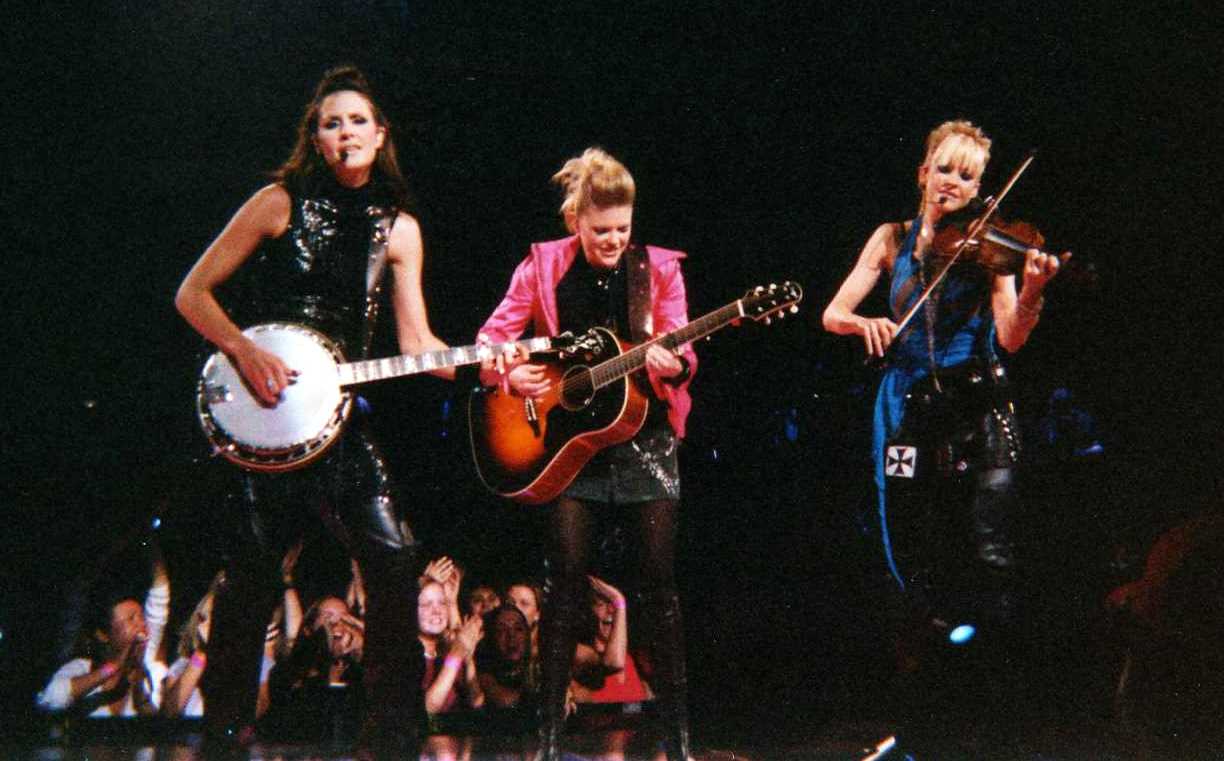

In contrast to this, according to Atrios, stand the Dixie Chicks (now renamed the Chicks), who underwent a massive backlash following singer Natalie Maine’s comment, just as the Iraq War began, that “We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.” Almost instantly, country music listeners rose up in anger. Sales of the Chicks’ music plummeted; concert tickets went unsold and tour dates were cancelled; protesters smashed and burned the band’s CDs and, at one event, ran over them with a tractor. Offended fans also called and wrote to radio stations to demand they stop playing the band, and radio stations obliged: by the end of March, the band’s airplay on country stations was down an estimated 29%, and in May two Colorado DJs were suspended by their station for playing Dixie Chicks songs. Whether or not these radio stations were sincerely offended by Maines’ statement, the vociferousness of the listener response made the band’s blacklisting inevitable. “Radio generally reflects the mood of the country,” said one radio analyst. “If radio perceives that its listeners are upset with the Dixie Chicks, they will act accordingly.”

Those who opposed the band’s treatment framed the issue as a matter of freedom of expression, and the boycott and blacklisting of the Chicks as contrary to American values. Country legend Merle Haggard complained that the attacks on the band were “like a verbal witch hunt and lynching.” In 2003, while the backlash was raging, Atrios’s blog approvingly quoted in full a statement from the program director at a Kansas City radio station explaining his decision to put the Chicks’ music back on the air despite listener comments running 80-20 against doing so. “Our Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines are over there fighting for our rights – and one of those is our Constitutional right to express an unpopular opinion,” the director explained. “The longer this has gone on, the more I had visions of censorship and McCarthyism.” Following the quote, Atrios encouraged readers to email the director “to express your thanks for him not being a brownshirt.”

And yet to conservatives at the time, the idea that the Chicks had been repressed at all, let alone in a manner reminiscent of Nazism, was as absurd as complaints about “cancel culture” are to many on the left today. On Instapundit.com, Glenn Reynolds posted “The Dixie Chicks: Learning the difference between capitalism and censorship,” linking to another blogger who spelled out that difference: “[The Dixie Chicks] have the right to say whatever they want (obviously) and we as the consumers, the people who can put money in their pockets or not, have the choice to stop purchasing their products and services. The beauty of capitalism.” One could see the logic: how could it be censorship for people to choose to stop listening to a band? And how could it be censorship for radio stations to pull that band’s music when people aren’t listening to it anyway? This reasoning was taken up by no less an Iraq War supporter than George W. Bush. In a 2003 interview with the President, Tom Brokaw used the example of the Dixie Chicks to point out the irony that the Iraq war was ostensibly about liberating people from oppression, yet some who protested it were being shouted down. Bush responded that while the band was free to say what they wanted, “they shouldn’t have their feelings hurt just because some people don’t want to buy their records when they speak out. You know, freedom is a two-way street.”

Seventeen years later, the essence of Bush’s argument—that boycotting or blacklisting someone for their political views is itself simply free expression, with no implications for the larger values of free speech—is perhaps the most popular response on the Left to claims, like that of the Harper’s letter, that “intolerance of opposing views” has gone too far in its pursuit of social and professional consequences for ideological wrongdoers. “Once more: THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS CANCEL CULTURE,” tweeted New York Times columnist Charles Blow in the wake of the Harper’s letter. “There is free speech. You can say and do as you [please], and others can choose never to deal with you, your company or your products EVER again.” Just before the letter was published, Osita Nwanevu took a similar line in The New Republic, arguing that self-professed liberals should take more seriously the right of freedom of association—which he defines as “the under-heralded right of individuals to unite for a common purpose or in alignment with a particular set of values”—as granting people and platforms the right to shun whomever they please. Nwanevu went so far as to say that since critics of “cancel culture” disregard this freedom of association, it is they, not their targets, who are acting illiberally. Writing in the Daily Beast, Laura Bradley touted so-called “cancelling” (Bradley, like Blow and many others, rejects the term) not as repression, but as a triumph of the “marketplace of ideas”: “losing your platform simply means that a company has decided the value you produce is not equivalent to the liability you present.”

So, by these lights, the Kansas City programming director who defied his listeners by playing the Dixie Chicks on air was barking up the wrong tree when he justified his decision by referring to the Constitution. If a member of a band says something controversial and emails are running 4-to-1 in favor of taking them off the air as a consequence, then the band is a liability and off the air they go, and neither the station nor the angry listeners who wrote in have done anything illiberal. Who could argue with that?

Finding perspective

Hypocrisy arguments have probably always been overused, and never more than today, when so many commentators have ten years of social media posts (not to mention, for some, another ten years of blog posts) to pore over looking for contradictions. It’s often a misdiagnosis, anyway; much of what gets called hypocrisy can be explained by people simply changing their minds (if sometimes too conveniently), and even more can be explained by the sincere difficulty of seeing connections between cases that are parallel but have their polarities reversed. If someone views attacks on their own side as repressive and attacks on the other side as righteous, it’s not a sign of lack of character—it’s only human.

A more productive way to use these past events is as a temperature check on our values. In the moment of controversy, we are inclined to form our opinions based on what those in our immediate circle are saying; as the tweets fly fast and furious it’s difficult to ground ourselves in some stable set of principles. The distance of history lets us step out of the partisan moment to interrogate what we really think. So instead of using the treatment of the Chicks, and the wider suppression of dissent in the post-9/11 period, to ridicule those who opposed cancellation then but support it now—or vice versa—we should use it think about why what happened was bad, beyond the fact that we were just as ashamed of Bush as Natalie Maines was. We should ask, what was wrong with the Dixie Chicks getting cancelled, if that’s what country music fans wanted? To answer that properly, it’s worth remembering just how bad things got right after 9/11, and how bad they stayed for years.

The broader media landscape

An early, prominent cancellation began less than a week after the September 11 attacks with TV host Bill Maher, and culminated in a literal cancellation of his show nine months later. On September 17, Maher said on his show Politically Incorrect that it was inaccurate to label the 9/11 hijackers “cowards”: “We have been the cowards, lobbing cruise missiles from 2,000 miles away. … Staying in the airplane when it hits the building, say what you want about it, [it’s] not cowardly.” The usual backlash cycle followed: sponsors dropped the show, some ABC affiliates cancelled it, Maher appeared on talk shows to make futile apologies, and in June the show was killed. In case the chilling effect of Maher’s treatment was missed, White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer (who now rails against campus deplatformings) said that Maher’s remarks served as “reminders to all Americans that they need to watch what they say, watch what they do.”

The 2003 cancellation of Phil Donahue’s short-lived MSNBC talk show was less dramatic—there was no single moment of controversy as there was with Maher—but an internal company memo recommending the move fretted that the liberal host would be a “difficult public face for NBC in a time of war” and warned against maintaining a show that would be “a home for the liberal antiwar agenda at the same time that our competitors are waving the flag at every opportunity.” (This was in the years before MSNBC found its niche as a liberal alternative to Fox News.)

Less prominent media figures also lost jobs for voicing dissent, in cases that passed largely beneath the public radar, obscured by the earth-shaking aftermath of the attacks. Two newspaper columnists, one in Oregon and one in Texas, criticized how Bush performed on 9/11; both were fired. A German composer made esoteric remarks that were interpreted as celebrating the attacks; a New York concert of his work was canceled, despite his protestations and apologies. Such moves could be justified, not only by the need for sensitivity towards the victims of a heinous crime, but by the need for national unity during wartime. Even the most anodyne cultural events could fall victim to this rationale: in 2003, a few weeks into the invasion of Iraq, the baseball Hall of Fame cancelled a 15th-anniversary celebration of the movie Bull Durham because of the anti-war statements of stars Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon, statements which “ultimately could put our troops in even more danger,” according to the president of the Hall.

In this environment, avoiding controversy became a survival strategy. After what befell the Dixie Chicks, Madonna, of all people, pulled the music video for her song “American Life,” which depicted her throwing a grenade at a George W. Bush lookalike. In a statement, she explained “I do not want to risk offending anyone who might misinterpret the meaning of this video.” Of course, plenty of artists felt free to criticize the war and the Administration—I was at Coachella 2004, when Wayne Coyne of the Flaming Lips led the crowd in a “Stop Bush” chant. But in the mainstream, a culture of hyper-sensitivity reigned, a perception that artists and companies were safer, not only avoiding stances that challenged the militaristic consensus, but avoiding any reference to the subject at all.

In the immediate wake of the attacks, Clear Channel (now iHeart Media) issued a comically comprehensive memo of songs that its radio affiliates “might not want to play,” listing not only songs about war and violence (including all songs by Rage Against the Machine), but songs having to do with airplanes, New York, September, and even Tuesday (since 9/11 fell on a Tuesday). Even simple and happy songs, like “What a Wonderful World,” were proscribed as being in bad taste. The Clear Channel memo fits a familiar pattern: when an outraged reaction can arise from so many unexpected quarters, producers and distributors are as restrictive as possible in what they put out, out of an abundance of safety.

The patterns that emerge from considering the cases above are familiar from our current vantage point. One is that, while the most prominent cases of shunning affected rich celebrities who bounced back with little long-term harm—Bill Maher got a new show in 2003, and the Dixie Chicks swept the 2007 Grammys—less attention was paid to more marginal figures who suffered consequences, to say nothing of those who found it prudent not to speak up at all. Another is that in every instance, the pressure to fire, cancel, and blacklist did not come from the government; it came from the public, or from what companies thought the public’s preferences were. For all that we liberals described the Bush administration as authoritarian, in this area, at least, they didn’t need to sully themselves; the people did it for them.

Where do we go from here?

What can this period teach us about the debates about liberalism and tolerance taking place today? One pragmatic lesson, of course, is that the market forces we deploy to inflict consequences on those we see as enemies or transgressors can, when the wheel turns, be used on us. Some may dismiss so-called cancellations as simply the workings of “the marketplace of ideas,” but the marketplace of ideas, like any marketplace, has its reversals and its bubbles, and positions that seem strong now may suddenly find themselves sharply devalued. To extend the metaphor, the liberal value of tolerance can be seen as a kind of ideological safety net, offering thinkers security even in the event of a market crash.

The more important reason for liberals to consider the post-9/11 period, though, is what it can tell us about that marketplace’s limitations as the sole arbiter of free expression. The view taken by conservatives in 2003 and many liberals today, that boycotting and blacklisting are protected freedoms, is compelling for one simple reason: it’s indisputably correct. Blow and Nwanevu are correct that people are free not to deal with anyone they please; Elizabeth Picciuto is correct that “Boycotts are speech. People express themselves through their actions, trying to persuade others not to patronize a business”; Rabbi Ruti Regan is correct that “Curation is speech. Editorial policy is speech. Making decisions about what to invite onto your platform is speech.”

But as history tells us, identifying speech as such isn’t sufficient to settle the argument over whether that speech is repressive. Something can be protected speech and still work to stifle the free expression of others, one of the many binds that make liberal society so difficult to maintain. To liberals living through the post-9/11 clampdown, the question wasn’t whether country fans protesting the Dixie Chicks were engaging in speech, or whether NBC was free to cancel Donahue’s show, or whether Clear Channel was within its rights to tell its stations not to play “War” by Edwin Starr; the answer to all these questions was clearly “yes.” The question was whether political stances should in themselves lead to artists and commentators being shut out of the public sphere, and what the consequences of this were likely to be on the broader discourse.

That repressive speech is a freedom makes the question of cancellation harder, not easier, because freedoms carry responsibilities: the citizen has to anticipate what effect, even if only marginally, their free exercise will have in shaping society. For years after 9/11, much of the citizenry decided to use its speech rights to pressure the media and other institutions to enforce conformity, and those institutions largely did as they were asked. We now have to decide how far we want to follow those citizens’ example. As George Bush reminded us, freedom is a two-way street.

Featured Image is Dixie Chicks in Concert in Madison Square Garden in 2003