Diversity and Forbearance

In moments of crisis for the liberal democratic system, it’s worth asking ourselves whether the system is even worth it. When human rights are being violated and unjust wars waged in our names, when some of us can be killed by the authorities with impunity, and when a liberal democracy has just installed a man with illiberal and authoritarian tendencies as president, we’re faced with tough questions. What can justify continued faith in the liberal democratic system?

Forbearance and irreconcilable difference

The dream of liberal democracy is that all kinds of people, despite deep differences in their values and beliefs about the world, can live together in social and economic cooperation. But some of our values necessarily conflict with one another, not in the sense that we have opposing interests, but in the sense that sometimes our values require certain actions from others, actions their values prohibit. And yet sometimes democratic outcomes put these values at loggerheads.

Consider abortion and reproductive freedom. To the pro-life person, a human soul—as unique and precious as any other—is present in an embryo from the moment of conception. Abortion thus represents a legally sanctioned holocaust of millions of innocent lives. The thoughtful pro-lifer may acknowledge that it isn’t fair that women have to shoulder the burden, but in their minds the right to life trumps considerations of fairness.

By contrast the pro-choice person simply does not see the fetus (at least during the periods when 99% of abortions are performed) as sufficiently developed to suggest it has a soul. The pro-choicer thus sees abortion restrictions as unconscionable violations of bodily autonomy, indeed as a dehumanizing slavery by which women’s bodies are treated as incubators for offspring they don’t want and didn’t ask for, significantly interfering with their lives, projects, and well-being. The thoughtful pro-choicer recognizes that they might view the matter quite differently if they considered fetuses fully human and deserving of human rights themselves, but see no reason to.

The example of abortion shows that thoughtful, good people may simply parse the world differently, even when they understand the alternative positions. No amount of good faith engagement will prevent such different construals of the world from leading to irreconcilable differences.

It’s not hard to come up with more examples. Animal rights activists see many animals as agents with interests and at least some degree of moral standing; others follow the long tradition of believing animals exist primarily for human purposes, having no genuine interests of their own, and note that since animals cannot express their own alleged rights claims, human persons must do so, leading to a clash of ultimately human interests.

Free speech absolutists and sex worker rights advocates construe pornography as an issue of freedom of expression; some feminists point out that the issue is more akin to hate speech and slander against women, and is best understood as propaganda for male supremacy and female objectification that can materially harm women with its spillover effects. The question of wearing the hijab in public turns on whether it is understood in terms of religious liberty or freedom from sexist oppression.

Such fundamental perspectival differences abound in the economic realm as well. Libertarians and market anarchists proclaim taxation and redistribution are literally theft, while radicals on the left claim the same about private property and capitalist profits. Many moderates don’t fully endorse these stark statements but are nonetheless swayed by one polar perspective more than the other and their understanding of economic questions in politics is colored by this.

With fundamental perspectival differences on such important questions, partisans cannot reasonably hope to ever fully, finally win in the democratic arena. Occasionally some such question is suddenly decided, like slavery, but when and how this shift happens is a bit of a mystery. In the case of slavery in America, the perspectival shift only happened after a massive and bloody political failure, the costs of which make it a frightening example to try to follow.

It’s not surprising that democratic cynicism has been creeping up along with political polarization in recent years. A large segment of voters in the West has begun to opt for anti-system candidates who sell themselves as not only anti-establishment but also uniquely capable of cutting through gridlock and imposing their will (or “the people’s will”). Anti-system voters who doubt any such unique abilities at least view anti-system candidates as “bulls in the china shop,” the idea being that the system is so bad that if a few institutions get destroyed, whatever is rebuilt is bound to be an improvement. These temptations are powerful, but misguided.

For the sake of the liberal democratic peace, the conservative Christian must patiently accept that millions of innocent souls will be slaughtered, because, for the nonce at least, the pro-choice perspective mostly prevails as the law of the land. The animal rights activist must abide the wholesale torture and slaughter of millions of sentient creatures. And, to continue with our few examples chosen from among many, the radical feminist must suffer the propaganda of male domination paraded around as a core freedom.

Is the liberal peace worth it? The only alternatives are to exit the political community or to take up arms or otherwise subvert the political peace. But usually—when democracy isn’t suffering a crisis of confidence—most conservative Christians, earnest animal welfare advocates, and radical feminists neither seek to exit the political community nor take up arms.

Both options, of course, have their mundane difficulties. Attachments to family and friends and the ability to find work are high hurdles to moving even in the absence of more bureaucratic barriers. And political violence is criminally prohibited. But keeping the peace of political liberalism is worth the struggle for more fundamental reasons. Purely political emigration is a kind of shallow escapism.

In our examples, the perceived problems of mass slaughter and patriarchy will persist after the departure of dissenters; indeed, such exit would seem to dampen dissent. The separatist suffers similar problems along with a hard coordination problem of moving people en masse. These options also offer only ephemeral relief. All communities are cut through with important ideological divisions. The political emigrant will replace one set of perspectival impasses with another, while the separatist will achieve some uniformity for a while, but such unanimity will inevitably degrade over time. Even individuals who grow up in the same communities may develop divergent understandings.

Actual violence, meanwhile, has well-known rhetorical difficulties. Political violence is rightfully understood as terrorism, and rarely persuades anyone on the merits of one’s perspective. Violence also actively alienates people from the cause and often inspires retaliatory violence. Whatever the rhetorical successes of violence, for the present article I assume private violence is beyond the pale.

Democracy, among its many virtues—and for all its faults—is an outlet for continuing dialogue on contentious issues. It keeps people talking and provides periodic opportunities for factional victories that offer the hope of at least nudging policies in one’s preferred direction. Living peacefully in a liberal democracy thus requires a powerful commitment from every individual with strong beliefs. Consciousness-raising, persuasion, activism, civil disobedience, and political organization are valid paths for change. These are painfully slow and uncertain, but they acknowledge the reality of earnest and reasonable differences in beliefs, and they treat one’s political opponents with the respect due to equals.

Forbearance under oppression

Fetuses and animals cannot speak for themselves. They cannot vote under any plausible scenario, and they certainly cannot organize protests. Political dialogue around these entities is just that: around and over. But the rights and freedoms of groups of people who can speak for themselves are also regularly threatened by the political back and forth. Liberal political theorists prefer to set aside core rights of the individual as beyond political dispute or tampering. Theorists of course have good reason to do this, but in real democracies individuals belonging to disfavored groups have had to struggle mightily to have their rights and dignity recognized. Even constitutional protections—themselves hard won always—are ultimately at the mercy of a political community that can turn inward and illiberal at the scent of threat.

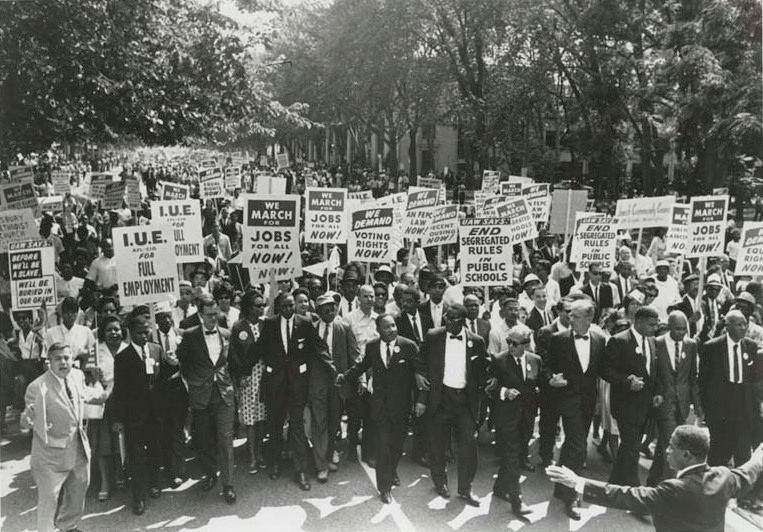

In America, you can draw a line from the Three Fifths Compromise and chattel slavery through Jim Crow, redlining, and straight on to the racially disproportionate War on Drugs and our current mass incarceration state. Black Lives Matter arose to call attention to the impunity with which white persons can so often kill black persons, only to be met with #bluelivesmatter and #alllivesmatter in response, diminishing their legitimate concerns that black lives are not afforded the same rights and dignity, in effect if not de jure. Meanwhile even sacred suffrage, enshrined in the Constitution after bitter struggle, is under constant assault as Republican state governments attempt to disenfranchise blacks with demographic “surgical precision.”

Immigrants—now most conspicuously Latin Americans, Arabs, and Muslims, but historically Chinese, Japanese, Irish, Italians, even Germans during the early days of the republic—face a uniquely unstable situation with respect to their rights. “Illegal” immigrants of course can be deported more or less according to the prerogatives of the executive branch. But as the political winds change, even immigrants who are crossing their t’s and dotting their i’s in the manners so tortuously prescribed [pdf] are at risk for sudden changes to the rules. And of course in the current environment there is a real risk that Muslim Americans irrespective of legal status will be unjustly detained, sequestered, or be victimized by tacitly approved private pogroms.

Women still haven’t won full social equality with men in various ways. They’re still too often treated as vessels for the next generation, sexual assault is still a scourge, and sexism ranging from casual to harassing still colors much of their lives and plans. Gays and lesbians have managed a coup with the social and legal recognition of their rights to marry, but in a resurgent right wing, these victories must feel tenuous at best. The very bodies of trans persons are viewed as immoral, and they are killed in disproportionate numbers. I’m just skimming the surface here.

When liberal democrats like myself raise the hue and cry to rally once more around liberal democratic institutions, we often do so from a position of privilege, without acknowledging that recommitting to liberal values—recommitting to “the system”—asks significantly more from some of us than it does from others.

It is very easy to see rallying cries for liberalism as white, upper class elite men suddenly feeling the reeling, the doubts, and the fears of the system tottering that has cossetted them—us, I’m speaking of my own massive privilege—so much. Suddenly we are feeling uncertain, not only of our rights, but of the basic shape and character of our society. When so many folks who look like me felt shock and horror on November 8th, we felt just a little of what so many of our fellow citizens feel even under the liberal democratic system that we tout as essential for social progress.

The liberal democratic system, for all its faults, has benefited the marginalized. We have seen progress, since abolition, since women’s suffrage, since the Civil Rights Movement and the Pill and freedom to marry. The economic growth generated by the system has benefited even the poorest among us, despite the economic turmoil of recent years and despite the ways the economy is rigged in favor of the already privileged. It goes without saying that all societies have disadvantaged and disfavored groups and that it’s better to be marginalized in a liberal democracy than in any existing alternative.

All these things are true, but they sound hollow coming from an upper middle class white dude who is just suddenly out of his political comfort zone. And members of marginalized groups are likely tired of being told how to feel. The marginalized haven’t abandoned liberal democracy, and they have more to teach about forbearance and faith than folks like me. It was women who organized the Seneca Falls Convention and the suffrage campaigns that ultimately won women the franchise. It was black Americans who led protests and sit-ins and nonviolent resistance that led to the Civil Rights Act and victory over Jim Crow. Instead, it is the system liberal’s turn to listen, learn, and adapt the liberal program to truly embody the universal liberty and equality of its promises.

Forbearance, not passivity

One lesson from these past campaigns is that the forbearance required to advance liberal causes is anything but passive. Shikha Dalmia has recently discussed the abolitionist tactics that faith communities, civic organizations, and sanctuary state and local governments are using to resist the Trump Administration’s efforts to escalate deportations of peaceful people. Sanctuary jurisdictions are refusing to cooperate or lend their resources to deportation and faith groups are preparing Underground Railroad-style safe houses for migrants and others at risk.

There may seem to be some contradiction between the democratic forbearance I discussed in the first section with the abolitionist tactics that directly resist the implementation of policies enacted fairly through the legitimate legal channels. (This may not be the case for any specific executive actions currently in the news, but it’s plausible such actions will be enacted through correct procedures at some point.) There certainly is a tension here. But a look not only to our own national history but to the history of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience around the world informs us that these campaigns often provide us with our most inspiring national heroes and our greatest occasions for civic pride.

This kind of direct action to protect individuals directly threatened by those the liberal democratic system has empowered is partly how the system learns who is included within “universal” and who deserves liberty and moral equality. The forbearance required to allow the other side to win elections and enact policies despite our deep disapproval could not possibly have extended to slaves seeking their freedom. And it is doubtful that it extends all the way to peaceful immigrants and peaceful Muslim Americans allowing themselves to be forcefully separated from their families and livelihoods and either deported or detained in camps.

But what forbearance does require is that we continue talking to one another and continue listening. It demands that we respect the legitimacy of electoral outcomes and not resist the mundane functioning of the established governments, and to reserve civil disobedience only for specific unconscionable policies. Liberal forbearance demands we continue to recognize—as my colleague has put it—that our political foes whose visions of moral equality have shorter horizons than ours nevertheless remain members in full standing of our shared democratic institutions.