Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, The Woman who Ended Sterilization Abuse in the U.S.

From 1937 to 1960, one third of the population of mothers on the island of Puerto Rico were sterilized through manipulation and misinformation, while others became part of the first clinical trials for the first birth control pill after being misled to believe that the drug was already proven safe. The doctor who helped bring an end to these abuses, Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, was a Puerto Rican doctor from New York City. This unsung Hispanic doctor was a pioneer for reproductive rights, and her work changed medical ethics across the globe.

Born in 1929 in New York City, and growing up partly in Puerto Rico, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias was placed in less advanced classes due to her ethnic background despite excelling in class and being fluent in English. Like so many bright, underchallenged students, her luck turned when she met the right teacher. That teacher recognized her abilities and placed her in more advanced classes. In 1960, she completed her residency in San Juan and established Puerto Rico’s first infant health clinic. Thanks to the clinic, within three years, the hospital saw a decrease in the infant mortality rate by 50 percent. In 1970, she became the head of the pediatrics department at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, which served mostly black and Latino patients and was criticized by the Young Lords, a group of Puerto Rican activists, “for public health violations, crumbling facilities, and negligent care.” When the Young Lords staged occupations of hospital buildings in protest of the poor quality of care, she responded by training her staff to better understand the needs of the people they served and “aimed to find points of agreement among the Young Lords and the other groups who had a stake in the hospital.” She responded to civil disobedience, with collaborating with those in protest and educating her staff on inclusive practices.

Dr. Rodriguez-Trias believed that in order to improve society, we must empower and uplift underserved communities so they can have their most basic needs met. When describing her approach to public health, she states that “it was really determined by what was happening in society—by the degree of poverty and inequality you had.” Dr. Rodriguez-Trias’ awareness of the social positioning of healthcare would lead her to become the first latina to be elected president of the American Public Health Association in 1993. Her communal approach was met with success on many fronts. She advocated HIV awareness for people in Puerto Rico, low income and minority women across the nation, and lesbians, who weren’t informed how HIV could spread in lesbian sexual encounters. She was able to use her “code-switching” between Spanish and English “to mend the bridge between medical staff, colleagues, political leaders, and patients(…) facilitating an understanding of the inequalities, disparities in the community that was tied with poverty.”

Dr. Rodriguez-Trias stood for the Puerto Rican women facing eugenic abuse at the hands of doctors from the mainland who believed that overpopulation was the cause of poverty. She began studying medicine at the University of Puerto Rico in 1957, the height of the eugenic era. Forced sterilization was legal in much of the country at this time, but a woman on the island was 10 times more likely to be sterilized than a woman on the mainland. Women were misled to believe their sterilizations were reversible, or they were forced to undergo sterilization if they gave birth in a hospital. Women who were on welfare were supposed to keep their benefits if they refused sterilization, but noncompliance to this regulation and others was common.

Women’s health clinics that were performing sterilizations were all over the island by the time that birth control was ready for the first human trials. Sanger, who “endorsed the 1927 Buck v. Bell decision(…) in which the Supreme Court ruled that compulsory sterilization of the ‘unfit’ was allowable under the Constitution” also endorsed doctor Gregory Pincus’ decision to begin the first trials of the first birth control pill on women in Puerto Rico, as the facilities that performed the sterilizations could easily become testing sites, and testing birth control wasn’t outlawed in Puerto Rico, while it was banned in most of the country. Dr. Rodriguez-Trias worked in hospitals on the island from 1960 to 1970 and noted that “one of the things that seemed pretty obvious(…) was that Puerto Rico was being used as a laboratory(…) for the development of birth control technology.” She was especially unhappy with the lack of informed consent, noting that “birth control is really carried out, people are given information, and the facility to use different kinds of modalities of birth control,” and that population control would never compare to the freedom that birth control ought to provide.

Sanger’s eugenics-based justification of birth control relies on the idea that class-based population control could transform society. She saw “the inferior classes” as “the feeble-minded, the mentally defective, the poverty-stricken classes” while she saw “the educated and well-to-do classes” as “the mentally and physically fit,” noting that self-imposed birth control can help fix the “unbalance between the birth rate of the ‘unfit’ and the ‘fit’” so long as we educate the unfit on what makes someone fit to be a parent. Dr. Rodriguez-Trias, on the other hand, rejected these eugenic justification for reproductive choice, distinguishing birth control from population control as she says “birth control exists as an individual right(…) while population control is really a social policy that’s instituted with the thought in mind that there’s some people who should not have children or should have very few children, if any at all.”. Dr. Rodriguez-Trias further explained that Sanger’s argument didn’t preserve a woman’s right to choose because “young white middle class women were denied their requests for sterilization,” while “low income women of certain ethnicity were misled or coerced into them.” A eugenics-based approach to reproductive healthcare will always result in individuals losing choice because the idea of eugenics is based on the concept of suppressing the freedom of individuals for the sake of a fitter society.

Dr. Rodriguez-Trias saw that pairing up with any oppressive institution for the sake of immediate gains would always turn back to this and believed that in order to create an enduring system that protects reproductive choice, we must

guard against the tendency to form too quick alliances when we are confronted by violent opponents. The search for protection from the seemingly powerful forces against women’s rights could lead us to ally with population control advocates who speak of women’s rights only out of opportunism.

We can’t appeal to our oppressors in an attempt to give women freedom in the form of a consequence of oppressive political theory, especially when the theory at hand is intended to take away the rights of individuals. When we stay inside the boundaries of the aims of those in power because they’ve painted their unchanged worldview in a cheap, seemingly progressive veil, we fail to fight for systemic change that alters the foundation upon which all other rights live. Audre Lorde, a black lesbian feminist writer, expresses Dr. Rodriguez-Trias’ sentiment poetically: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Dr. Rodriguez-Trias’ believed that in order for the U.S. to protect reproductive rights, we needed to make radical changes to the public health system, which called for “reintegrating health care for women and their families; redirecting reproductive rights policies; establishing prevention as a health care priority; replacing punitive with supportive policies for the social problems of the poor.” She was a founding member of the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse in 1970, and established laws that ended the practice mandated sterilization in America, which are still in place. She was also a founding member of the Women’s Caucus of the American Public Health Association and a founding member of the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse in 1979. Through her life’s work, she demonstrated that a movement’s cause ought to be the foundation from which we build lasting systemic change. “Alliances of women from different nations, ethnic groups, indigenous peoples, races, and social classes,” she stressed, “must be based on mutual respect, adherence to key principles of democracy, and, most importantly, on a commitment toward eliminating gross inequities among groups and nations.”

Helen Rodriguez-Trias took her approach to medicine to a global scale, expanding the availability of public health services for women and children in socially disenfranchised communities in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East by supporting abortion rights, putting an end to enforced sterilization, and fighting to make neonatal care accessible to all. In 2001, she received the Presidential Citizen’s Medal for impact on medical care for women, children, people with HIV and AIDS, and the poor, before dying of complications from cancer in 2001. Even toward the end of her life, she showed humility and compassion, indiscriminately valuing all communities of people, saying that “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life. Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment. It’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.”

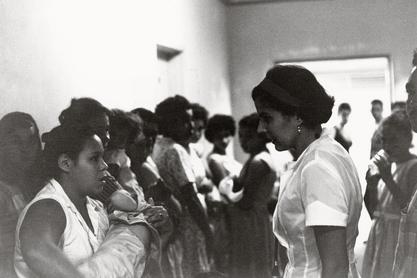

Featured Image is Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias speaking to new mothers, from the National Library of Medicine