Drawing on Ukrainian Republican Roots

The egalitarian history of Ukrainian identity.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the question of Ukrainian identity has taken on sharper importance, both in Ukraine and outside it. This is true for Ukrainians making enormous sacrifices for the sake of a sovereign state, of course, as the question is really one of what exactly they are fighting to preserve or to build. However, as Ukrainians have called on its neighbors and the international community to support its struggle, often using the language of freedom and democracy, they have run into a variety of counter-narratives that suggest that, in this case, there is no ‘nationhood’ worth defending, at least not at any appreciable cost. These narratives come in several varieties, but the most common refrain is that either Ukrainian nationhood is somehow artificial, existing only since the 1990s or, in an even more extreme telling, 2014, or that Ukrainian nationalism is somehow a fundamentally right-wing phenomenon.

The former rests on an understanding of Ukraine, as well as Belarus and perhaps other Slavic speaking states, as part of a larger ‘Russian world’ whose internal distinctions are artificial. The latter points especially to Ukrainian nationalists’ resistance to the USSR, and the modern state’s anticommunism (typical of former Eastern Bloc states), as indicative of a nation or people so steeped in right wing ideology that they must be forcibly deprogrammed; in this way Russia attempts to whitewash its invasion as ‘antifascism’, and independence for Ukraine as somehow spelling victory for ‘fascists’. While much of this rhetoric originates in Russia, it has found purchase among many western politicians and decision makers.

However, both narratives are dramatically at odds with the facts. Ukrainian nationalism can be traced back to the heyday of other European nationalist movements, and it is hardly an ‘invented’ tradition of the post-war era. Perhaps more importantly, the intellectual history of Ukrainian identity reveals a deep rooted tradition of republicanism and egalitarianism. These values were especially associated with Ukrainian nationhood due to its unique material circumstances under the rule of primarily foreign monarchs and aristocrats, and they continue to hold lessons for the Ukrainian people, and their supporters, today.

If one listens to Ukrainian patriotic songs from the nineteenth and 20th centuries without a deeper understanding, they might come to the conclusion that they tell a very paternalist narrative: an unwavering loyalty to the Ukrainian state, even beyond death, along with praise for the Ukrainian flag and land. However, such an interpretation would be both misleading and incorrect. The idea of the Ukrainian state was, in the pre-independence period, itself synonymous with the conception of self-governance, and developed as an opposition to foreign rule, landlordism, and autocracy. Thus, “dying\struggling for the Ukrainian state” meant a clear connotation of “dying\struggling for freedom” in the broadest meaning of the word. The idea of creating a Ukrainian state was rooted in the desire for self-governance—living according to one’s own will, making personal decisions, earning a living through one's own labor, speaking one's own language, and being free to express one's true self. The Ukrainian state, at its core, was self-governance, and any Ukrainian state that did not embody self-governance was a contradiction. A soldier in Lviv at the close of the Great War and dawn of a brief moment of Ukrainian self-governance wrote in his diary:

As if I was confused, I ran out into the street. I'm not going to sleep [...]. There is only one thing on my mind: in two hours - we will be free, free, we will have Ukraine, we will be masters in our own house!

The concept of "Ukrainianness"—what it means to be Ukrainian—emerged from social, national, and democratic struggles.

Unlike some other European states and stateless nations, Ukrainians were the nation without its own landlords and capitalists. Other people ruled over them—Polish and Russian lords. Due to this, a close link developed between the conception of national and social liberation. To drive out occupiers and colonists inherently meant to drive out exploitative social classes too. In the words of ethnographer Mykola Kostomarov, despite lacking a polity,

[Ukraine] did not vanish, because it did not know the king nor the [feudal] lord, there was a tsar, but foreign, and although there were lords, so alien, although those lords are from the Ukrainian kind, but did not speak Ukrainian, in essence bastards; but a real Ukrainian does not like either the king or the lord and knows only God

Ukrainians, living under Tsarist rule and the Polish aristocracy, were oppressed and denied the opportunity to thrive. It was seen as the rule of absolutism and the aristocratic regime both exploited Ukrainians, and the opposite was the answer against these problems—democracy and universal suffrage. Thus, Ukrainian struggle gained republican character.

The majority of the feudal lords, landlords, Tsars, and aristocrats were foreign rulers, imposing a colonial culture that solidified the final cornerstone of the national independence idea. It was about governing one's own affairs in one's own way, with the freedom for culture to flourish, just as it should in any other nation.The foundation of the Ukrainian state was thus built on the promise and hope of a government intimately connected with its people—focused on social equality, internationalism defined by the equality of nations, and democracy.

These points, and opposition to aforementioned oppressions, become a “canon” in Ukrainian national liberation movement. Only those movements who accepted all of these points rose to any prominence. Movements which took right-wing or far-right positions instead aligned with Russian or Polish interests as the question of political identity became the question of national identity. Being Ukrainian meant resonating with the plight of Ukrainians—slave-serfs, and resisting those forces who exploited them. In other cases, those right-wing actors presented themselves as “South Russians” or other identity aligned with foreign assimilation.

The first to find these strings that touched the needs of Ukrainian people were Ukraine’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko, and a Russian activist and scholar who took Ukrainian culture and struggle so close to heart that now he is treated as one of the greatest Ukrainians, Mykola Kostomarov. They both started a quest that would redefine the trajectory of Ukraine.

Together they founded the Cyril-Methodius Brotherhood. Named after famous Eastern European Christian theologists, the Brotherhood put as its goal an achievement of a confederation of independent and republican Slavic states based on the ideals of Gospel interpreted in a radically social and democratic way.

The organization in its beliefs promoted a unity of Slavic states in an EU-like entity, where there would be “no rich or poor”, “no lord or tsar”, and where the leader is elected and judged before popular assembly—a vision of parliamentary socialist democracy. Ukraine in that system of beliefs was a unique cornerstone. Due to its cossack past, and its lack of aristocratic elites, the “Brotherhood” concluded that Ukrainians still remembered the concept of freedom not poisoned by elite capture.

In its founding document, a “Book of Genesis of Ukrainian People”, Mykola Kostomarov underlined its vision of history and the future. There, he criticized Greeks for slavery, Romans for corruption of Christianity for the benefit of the elites, and the French Revolution for idolizing egoism, commerce and national pride. “Genesis” is full of criticism of wealth inequality as incompatible with Christianity. It advances a nationalist, republican but universalist vision—where the countries should put away extreme nationalism and arrogance for the image of common humanity, where nations exercise self-governance, and people have individual freedom and social equality.

Priority of commerce over human connections, pride, egoism, and inequality—both political and economic—were in the “Brotherhood’s” opinion bringing humans farther from God, for which God punished people with crises, wars and instabilities. It was an interesting analysis, combining both religious and secular perspectives on how such things as unequal wealth redistribution leads to the downfall of nations and peoples.

The “Brotherhood” existed from 1845 until 1847, and had just 13 members. But it put seeds that would grow into a massive democratic movement. Its ideology, in a secularized way, had its influence on all Ukrainian organizations leading to the 1917 Ukrainian revolution.

After the “Brotherhood,” the first Ukrainian political party, created in 1890, was the Ukrainian Radical Party. It combined the notion of ethical (liberal) socialism and democratic nationalism. The impulse of democratic egalitarian populism of Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood took root in form of powerful socialist movements that oriented cooperatives and communities, and saw progress for Ukraine in achievement of its independence and liberation from the Empires, strong constitutionalism and rule of law with respect to the national minorities and natural rights of people, women suffrage and decentralization. One of the unique features for Radicals was their support for Jewish territorial autonomy, a demand voiced even before Jewish organizations in Ukraine.

With a slight lag, Ukrainian socialism was followed by social-democratic movement. The difference between “Social-Democrats” and “Socialists” in Ukraine was based on doctrines. Those who called themselves SD followed the thought of the German Social-Democratic Party, and especially Marx, Engels and Lassaille. Socialists were those on the radical left, who didn’t share Marxist ideology due to its perceived doctrinairism, urbanist orientation, or lack of pluralism. The final elements of the formation of Ukrainian political life was the National-Democratic movement. Closely associated with Republican and left-wing ideals, National-Democrats moderated visions of Brotherhood and Radicals, and instead of socialist transformation argued for creation of a welfare state and cross-class cooperation.

Ukrainian political movements were strengthened by its growing cooperative movement, which in Ukraine developed in unique directions. Where in other countries cooperatives were part of utopian practice or economic cooperation, in Ukraine cooperative movements gained a strong political, social and cultural importance. The first cooperative activists, inspired by the ideology of Brotherhood, underlined the role of cooperatives as a broad tool of civic education and self-defence from economic exploitation, social inequality and cultural assimilation. For cooperative activists, the cooperative movement was a torch-bearer of the idea of Ukrainian national liberation, and held a role of communal care, self-education, preservation and development of culture. It financed schools and libraries, language classes, technical education, organized cultural events, such as theater, festivals, etc. The Cooperative movement was seen as forging future Ukrainian democratic life—there, people learned compromise and civic virtue, finance, the importance of community; due to cooperative help, they learned Ukrainian history and culture, and had the possibility to provide education for the children.

This image of cooperation as a central agent in national self-defence played a major role in development of the cooperative movement. The first Ukrainian cooperatives appeared in the 1860s, in the 1880s there were more than a hundred cooperatives, in 1895—around 300, and more than 6,500 in 1913. During the Revolution of 1917 Ukraine functioned as a cooperative state, with the majority of the economy governed through cooperatives, of which there were more than 22,000 (for comparison, UK now has 7,000, with more than 3 times higher population than Ukraine during the Revolution). Half of the Ukrainian Revolutionary government was from the Cooperative movement - rather than out of a traditional aristocracy or strongman government, both frequent fates of newly independent nations.

This deep sense of communality, civic virtue, cooperation and national unity was accompanied and premised by a great sense of individual freedom. It was argued that both collective and individual dimensions of rights are codependent and one suffers without the other. Thus, all the major Ukrainian Parties emphasized the need to uphold individual rights as a necessity for development of nationality and virtue, as well as for securing a person's and nation’s dignity.

Development of Ukrainian national liberation movement, both its cooperative and political counterparts, resulted in the Ukrainian 1917 Revolution and the formation of Ukrainian People’s Republic—arguably the first modern democratic socialist state in the world.

Governed by pluralist Ukrainian Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and Marxist Ukrainian Social-Democratic Workers Party, it accomplished creation of a de-facto cooperative social state, implemented bold and innovative national reforms, such as law on national-personal autonomy, and made serious progress in anti-colonial struggle of the region. Ukraine became an example for many revolutions to follow soon: Crimean and Belarus, Georgian, Bashkir, Bukhara’s and other social-republican revolutions during the Russian civil war.

This is just one of many progressive pages of Ukrainian history mostly forgotten in modern debate. Ukrainian history is misrepresented, while the Central and Eastern European region is treated as a historically conservative place. All of this creates a place for newfound xenophobia against Ukraine and the region, even from the progressives, who too often conflate national struggles with reactionary movement and look with suspicion on any movement identifying itself as ‘nationalist’. Examining the ways in which Ukrainian identity historically aligned with egalitarian and republican values, on the other hand, can help broaden progressives’ understanding of the multifaceted struggle for Ukrainian independence beyond reactionary caricatures—caricatures often originating from imperialist propaganda. More broadly, the history of Ukrainian nationalism provides yet more examples of ways in which liberal values and national identity can work constructively together rather than being perpetually at odds with one another.

At the same time, there is much to learn in the broad, unique Ukrainian republican and socialist tradition, and finally place it in its rightful place in the history of democracy, and the history of socialism. Unfortunately, as has been seen in Ukraine where the government more and more relies on neoliberal ideology, principles can often be forgotten or fade over time. However, it’s crucial to reflect on them, preserve their progressive essence, and build upon them. By drawing on the aspirations of the past, we can shape a prosperous, inclusive, egalitarian and democratic future for all.

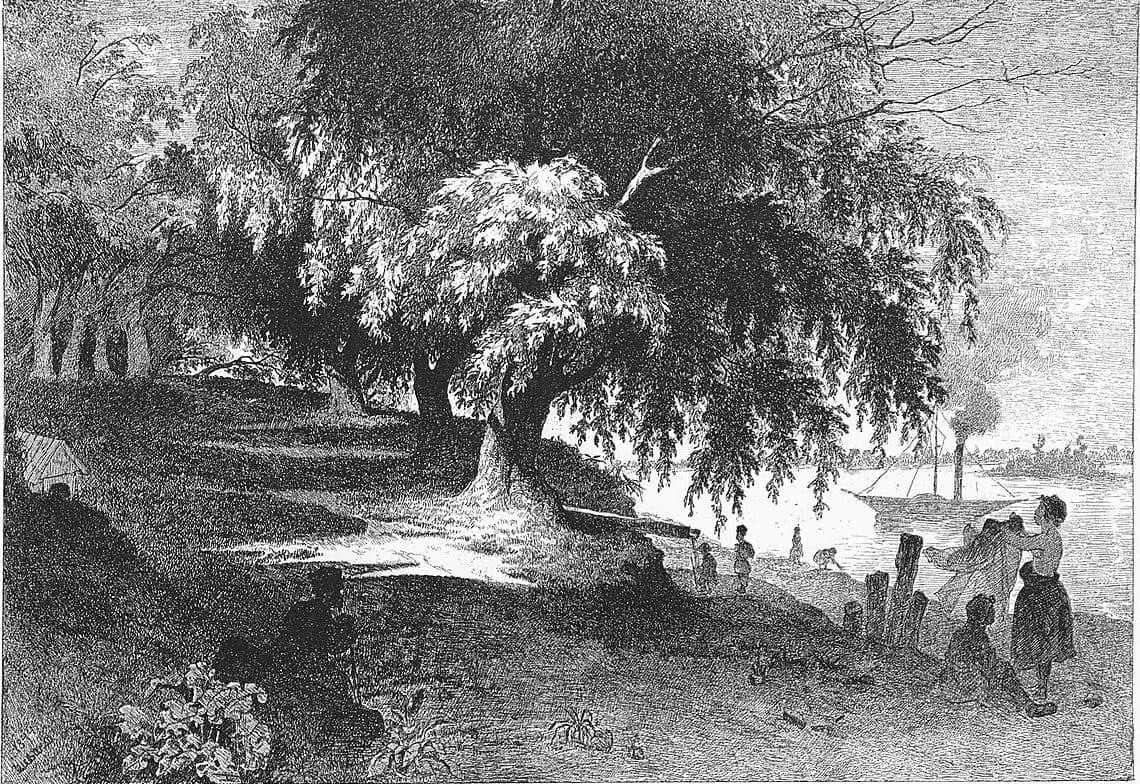

Featured image is In Kyiv, by Taras Shevchenko